The Rest Is History

Published 5 Jun 2025This is the final episode of our series on Hannibal, which is the second season on Carthage, the whole series is here: Rome Vs Cathage

Part 1 of our series on Hannibal is here: Hannibal: The Rise of Rome’s Greatest Nemesis

How did the Battle of Cannae — one of the most important battles of all time for Ancient Rome, with a whole Empire at stake, and a reputation that had reverberated across the centuries — in 216 BC, unfold? What brilliant tactics did Hannibal adopt in order to overcome the Roman killing machine, with its vast numbers and relentless soldiers? Why did so many men die in such horrific circumstances? And, what would be the outcome of that bloody, totemic day, for the future of both Carthage and Rome?

Join Tom and Dominic for the climax of their epic journey through the rise of Hannibal, and his world-shaking war against Rome, in one of the deadliest rivalries of all time.

00:00 Context to the battle

08:30 Prelude to the battle and their plans of attack

37:28 The battle

(more…)

August 2, 2025

The Bloody Battle of Cannae | Animated(ish) Episode

July 23, 2025

QotD: The legion of the Middle Republic

The basic building blocks of Roman armies in the Middle Republic are the citizen legion and the socii alae or “wing”. A “standard” Roman army generally consisted of two legions and two matching alae. but larger and smaller armies were possible by stacking more legions or enlarging the alae. We’re not nearly so well informed as to the structure of the alae of socii (the socii being Rome’s “allied” – really, subject – peoples in Italy), except that they seem to have been tactically and organizationally interchangeable with legions. Combined with the fact that they don’t seem archaeologically distinctive (that is, we don’t find different non-Roman weapons with them), the strong impression is that at least by the mid-third century – if not earlier – the differences were broadly ironed out and these formations worked much the same way.1 So, for the sake of simplicity, I am going to discuss the legion here, but I want you to understand (because it will matter later) that for every legion, there is a matching ala of socii which works the same way, has effectively the same equipment, fights in the same style and has roughly the same number of troops.

With that said, we reach the first and arguably most important thing to know about the legion: the Roman legion (and socii ala) of the Middle Republic is an integrated combined arms unit. That is to say, unlike a Hellenistic army, where different “arms” (light infantry, heavy infantry, cavalry, etc.) are split into different, largely homogeneous units, these are “organic” to the legion, that is to say they are part of its internal structure (we might say they are “brigaded together” into the legion as well). Consequently, whereas the Hellenistic army aims to have different arms on the battlefield in different places doing different things to produce victory, the Roman legion instead understands these different arms to be functioning in a fairly tightly integrated fashion with a single theory of victory all operating on the same “space” in the enemy’s line.

And you may well ask, before we get to organization, “What is that theory of victory?” As we saw, the Hellenistic army aims to fix the enemy with its heavy infantry center, hold the flanks with lighter, more mobile infantry (to protect that formation) and win the battle with a decisive cavalry-led hammer-blow on a flank. By contrast, the Romans seem to have decided that the quickest way to an enemy’s vulnerable rear was through their front. The legion is thus not built for flanking, its cavalry component – while ample in numbers – is distinctly secondary. Instead, the legion is built to sandpaper away the enemy’s main battle line in the center through attrition, in order to produce a rupture and thus victory.

To do that, you need to create a lot of attrition and this is what the manipular legion is built to do.

The legion of the Middle Republic is built out of five components: three lines of heavy infantry (hastati, principes and triariivelites), and a cavalry contingent (the equites). Specifically, a normal legion has 1200 each of velites, hastati and principes, 600 triarii and 300 equites, making a total combined unit of 4,500. Organizationally, the light infantry velites were packaged in with the heavy infantry (Polyb. 6.24.2-5) for things like marching and duties in camp, but in battle they typically function separately as a screening force thrown forward of the legion.

So to take the legion as an enemy would experience them, the first force were the velites. These seem to have been deployed in open order in front of the legion to screen its advance. These fellows had lighter javelins, the hasta velitaris (Livy notes they carried seven, Livy 39.21.13), no body armor and a “simple headcovering” (λιτός περικεφάλαιος, Polyb. 6.22.3), possibly hide or textile; they also carried a smaller round shield, the parma, and the gladius Hispaniensis for close-in defense (Livy 38.21.13). These are, all things considered, fairly typical ancient javelin troops, aiming to use the mobility their light equipment offers them to stay out of close-combat.

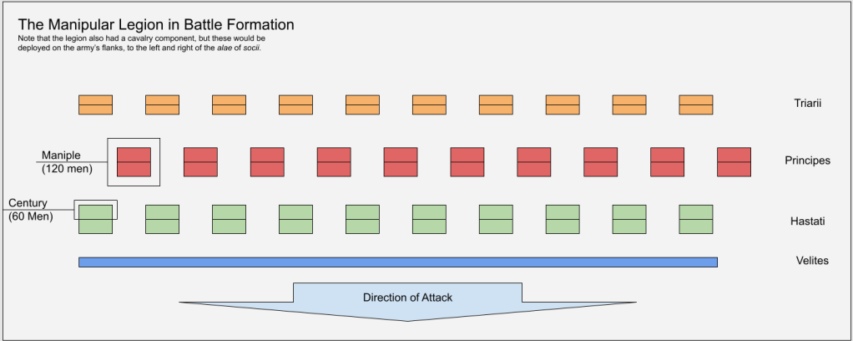

Behind the velites was the first line of the heavy infantry, the hastati. These fellows were organized into units called maniples (lit: “a handful”) of 120, which in turn are divided into centuries of 60 each. The maniples are their own semi-independent maneuvering units (note how much smaller they are than the equivalent taxeis in the phalanx, this is a more flexible fighting system), each with its own small standard (Polyb. 6.24.6) to enable it to maintain coherence as it maneuvers. That said, they normally form up in a quincunx (5/12ths, after a Roman coin with the symbol of five punches, like on dice) formation with the rear ranks, as you can see above.

The hastati (and the principes, who are equipped the same way) have the large Roman shield, the scutum, two heavy javelins (pila), the gladius Hispaniensis sword, a helmet (almost always a Montefortino-type in bronze in this period) and body armor. Poorer soldiers, we’re told, wore a pectoral, wealthier soldiers (probably post-225, though we cannot be certain) wore mail. That is, by the standards of antiquity, quite a lot of armor, actually – probably more armor per-man than any other infantry formation on their contemporary battlefield. That relatively higher degree of protection – big shield, stout helmet (Montefortino’s in this period range from 1.5-2.5kg, making them unusually robust), and lots of body armor – makes sense because these fellows are going to aim to grind the enemy down.

Note that a lot of popular treatments of this assume that the hastati were worse equipped than the principes; there’s no reason to assume this is actually true. The principes are older than the hastati, but the way to understand this formation is that the velites are young or poor, whereas for the upper-classes of the infantry (probably pedites I-IV) after maybe the first year or so, they serve in the heavy infantry (hastati, principes, triarii) based on age, not on wealth (and then the equites are the truly rich, regardless of what age they are; the relevant passage here is Polyb. 6.21.7-9, which is, admittedly, not entirely clear on what is an age distinction and what is a wealth distinction).

We’ve discussed the combat width these guys fight with already – somewhat wider spacing than most, so that each man covers the other’s flanks but they all have room to maneuver. It seems like the standard depth in the Middle Republic was either base-3 (so 3 deep on close order, 6 deep for “fighting” open order) or base-4 (so 4 and 8). Even in open-order with the maniples stretched wide (possibly by having rear centuries move forward), there would have been open intervals (10-20m) between maniples, which reinforces the role of a maniple as a potentially independent maneuvering unit – it has the space to move.2

Behind the hastati are the principes, with the same equipment and organization, slightly off-set to cover the intervals between the hastati, with a gap between the two lines (we do not know how large a gap). These men are slightly older, though not “old”. The whole field army generally consists of iuniores (men under 46) and given how the Romans seem to like to conscript, the vast majority of men will be in their late teens and 20s. So we might imagine the velites to be poorer men, or men in their late teens (17 being the age when one become liable for conscription) or so, while the hastati are early twenties, the principes mid-twenties and the handful of triarii being men in their late twenties or perhaps early 30s. The positioning of the principes isn’t to spare older men the rigors of combat, but rather to put more experienced veterans in a position where they can steady the less experienced hastati.3

Finally, behind them are the triarii, who trade the pila for a thrusting spear, the hasta, the Roman version of the Mediterranean omni-spear. These men are, as noted, the oldest and so likely the calmest under pressure and thus form a reserve in the rear. The three-line system here is what the Romans call a triplex acies (“three battle lines”). This wasn’t the only way these armies engaged and they could sometimes be formed up into a single solid line, but the triplex acies seems to have been the standard. We don’t know exactly how deep such a formation would run, but we have fairly good evidence that a legion might occupy a space around 400m wide (with some variation), meaning a whole Roman army’s core heavy infantry component (the two legions and two alae) might be some 1.6km (about a mile) across.

The equites, while organic to the legion organizationally, will be tactically grouped in battle to form cavalry screens on the edges of the army, not as a grand flanking cavalry “hammer”, but as flank-protection for the advancing infantry body (as a result, they tend to fight more cautiously). The equites in this period are heavy cavalry, with armored riders (after c. 225, that would be mail), using a shield and a hasta, along with a gladius as a backup weapon and thus serving as “shock” cavalry. Roman cavalry, if we look at their deployments, is generally ample in numbers, but the Romans seem to have been well aware it wasn’t very good, and sought allied cavalry (especially non-Italian allied cavalry) whenever they could get it. But the cavalry, Roman or not, was almost never the decisive part of the army.

Polybius tells us that the socii supplies more cavalry than the Romans and implies that there was a standard rule of three socii cavalrymen to every Roman equites, while socii infantry matched Roman infantry numbers (Polyb. 6.26.7). Looking at actual deployments though, we see that the socii tend to outnumber the Romans modestly, on about a 2:3 ratio, with socii cavalry only modestly outnumbering Roman cavalry.4 Consequently a normal Roman consular field army (of which the Romans generally had at least two every year) was 8,400 Roman infantry, around 12,600 socii infantry, 600 Roman cavalry and perhaps a thousand or so socii cavalry, for a combined force of 21,000 infantry (c. 5,000 light 16,000 heavy, so that’s a lot of heavy infantry) and 1,600 cavalry. That somewhat undersells the cavalry force the Romans might bring, as Roman armies also often move with auxilia externa (allied forces not part of the socii), which are very frequently cavalry-heavy (especially, after 203, that really good Numidian cavalry).5 By and large, it’s not that the Romans bring a lot less cavalry (as a percentage of army size), but that Italian cavalry tends to perform poorly and the as a result the Romans do not built their battle plans around their weakest combat arm.

Perhaps ironically, the Romans used their cavalry like Alexander and Hellenistic armies used their light infantry: holding forces designed to keep the flanks of the battlefield busy while the decisive action happened somewhere else.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IIa: How a Legion Fights”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-02-09.

1. On this, see Burns, M. T. “The Homogenisation of Military Equipment under the Roman Republic”. In Romanization? Digressus Supplement I. London: Institute of Archaeology, University College London, 2003.

2. On this, M.J. Taylor, “Roman Infantry Tactics in the Mid-Republic: A Reassessment”, Historia 63.3 (2014): 301-322.

3. To expound at some length on my own thoughts on how I think the wealth/age issue was probably managed, Dionysius (4.19.2) claims that the Romans recruited by centuries in the comitia centuriata such that the wealthy, divided into fewer voting blocks, served more often, and we know from Polybius that the maximum period of service for the infantry was sixteen years and from some math done by N. Rosenstein in Rome at War (2004) that the average service must have been around seven years. My suspicion, which I cannot prove is that the very poorest Roman assidui (men liable for conscription) might have only been serving fewer years on average and so it wasn’t a problem having them do all of their service as velites (the only role they can afford), whereas wealthier Romans (my guess is pedites IV and up) are the ones who age into the heavy infantry, with pedites I, whose members probably serve more than the seven-year average (perhaps around 10?) might make up close to 40% of the actual heavy infantry body (which is their balance in the comitia centuriata). The velites thus serves two important functions: a place to “blood” wealthier young Roman men to prepare them to stand firm in the heavy infantry line, as well as a place for poorer Romans to contribute militarily in a way they could afford. But I think that, once in the heavy infantry, the division between hastati, principes and triarii was – as Polybius says (6.21.7-9 and 6.23.1) – an age division, not a wealth division. Instead, the next wealth line is for the equites.

4. The data on this is compiled by Taylor, Soldiers & Silver (2020), 26-28.

5. Taylor, op. cit., 54-7 compiles examples.

June 11, 2025

QotD: “Pike and Shot” in the early gunpowder era

… this is why the pike[-armed infantry] fought in squares: it was assumed the cavalry was mobile enough to strike a group of pikemen from any direction and to whirl around in the empty spaces between pike formations, so a given pike square had to be able to face its weapons out in any direction or, indeed, all directions at once.

Instead, pike and shot were combined into a single unit. The “standard” form of this was the tercio, the Spanish organizational form of pike and shot and one which was imitated by many others. In the early 16th century, the standard organization of a tercio – at least notionally, as these units were almost never at full strength – was 2,400 pikemen and 600 arquebusiers. In battle, the tercio itself was the maneuver unit, moving as a single formation (albeit with changing shape); they were often deployed in threes (thus the name “tercio” meaning “a third”) with two positioned forward and the third behind and between, allowing them to support each other. The normal arrangement for a tercio was a “bastioned square” with a “sleeve of shot”: the pikes formed a square at the center, which was surrounded by a thin “sleeve” of muskets, then at each corner of the sleeve there was an additional, smaller square of shot. Placing those secondary squares (the “bastions” – named after the fortification element) on the corner allowed each one a wide potential range of fire and would mean that any enemy approaching the square would be under fire at minimum from one side of the sleeve and two of the bastions.

That said, if drilled properly, the formation could respond dynamically to changing conditions. Shot might be thrown forward to provide volley-fire if there was no imminent threat of an enemy advance, or it might be moved back to shelter behind the square if there was. If cavalry approached, the square might be hollowed and the shot brought inside to protect it from being overrun by cavalry. In the 1600s, against other pike-and-shot formations, it became more common to arrange the formation linearly, with the pike square in the center with a thin sleeve of shot while most of the shot was deployed in two large blocks to its right and left, firing in “countermarch” (each man firing and moving to the rear to reload) in order to bring the full potential firepower of the formation to bear.

Indeed it is worth expanding on that point: volley fire. The great limitation for firearms (and to a lesser extent crossbows) was the combination of frontage and reloading time: the limited frontage of a unit restricted how many men could shoot at once (but too wide a unit was vulnerable and hard to control) and long reload times meant long gaps between shots. The solution was synchronized volley fire allowing part of a unit to be reloading while another part fired. In China, this seems to have been first used with crossbows, but in Europe it really only catches on with muskets – we see early experiments with volley fire in the late 1500s, with the version that “catches on” being proposed by William Louis of Nassau-Dillenburg (1560-1620) to Maurice of Nassau (1567-1625) in 1594; the “countermarch” as it came to be known ends up associated with Maurice. Initially, the formation was six ranks deep but as reloading speed and drill improved, it could be made thinner without a break in firing, eventually leading to 18th century fire-by-rank drills with three ranks (though by this time these were opposed by drills where the first three ranks – the front kneeling, the back slightly offset – would all fire at once but with different sections of the line firing at different times (“fire-by-platoon”)).

Coming back to Total War, the irony is that while the basic components of pike-and-shot warfare exist in both Empire: Total War and for the Empire faction in Total War: Warhammer, in both games it isn’t really possible to actually do pike-and-shot warfare. Even if an army combines pikes and muskets, the unit sizes make the kind of fine maneuvers required of a pike-and-shot formation impossible and while it is possible to have missile units automatically retreat from contact, it is not possible to have them pointedly retreat into a pike unit (even though in Empire, it was possible to form hollow squares, a formation developed for this very purpose).

Indeed if anything the Total War series has been moving away from the gameplay elements which would be necessary to make representing this kind of synchronized discipline and careful formation fighting possible. While earlier Total War games experimented with synchronized discipline in the form of volley-fire drills (e.g. fire by rank), that feature was essentially abandoned after Total War: Shogun 2‘s Fall of the Samurai DLC in 2012. Instead of firing by rank, musket units in Total War: Warhammer are just permitted to fire through other members of their unit to allow all of the soldiers in a formation – regardless of depth or width – to fire (they cannot fire through other friendly units, however). That’s actually a striking and frustrating simplification: volley fire drills and indeed everything about subsequent linear firearm warfare was focused on efficient ways to allow more men to be actively firing at once; that complexity is simply abandoned in the current generation of Total War games.

Bret Devereaux, “Collection: Total War‘s Missing Infantry-Type”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-04-01.

June 5, 2025

D-Day and the Battle of Normandy on screen

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 4 Jun 2025Following on from the video about tank battles on screen, we look at the coverage of D-Day and the Battle of Normandy in movie and television dramas. This will be posted two days before the 81st anniversary of D-Day. As usual, this is a little about how good they are as drama and more about the historical background.

00.00 Introduction

02.50 Churchill

11.38 “Men on a mission” movies INTRO

16.45 Female Agents

20.20 The Dirty Dozen

32.06 The Big Red One

38.10 D Day: The Sixth of June

41.58 Patton

46.00 Night of the Generals

47.48 Breakthrough (1950)

49.36 Breakthrough (1971)

50.24 Pathfinders

57.48 Overlord

01.00.00 Storming Juno

01.04.48 My Way

01.12.12 They were not divided

01.17.24 Band of Brothers

01.51.00 Saving Private Ryan

02.33.45 The Longest Day

03.00.48 Conclusion and the “Ones that got away”For the discussion of the Pegasus Bridge project:

• Fighting On Film Podcast: Pegasus Bridge S…

May 9, 2025

Steyr AUGs of the Falkland Islands Defense Force

Forgotten Weapons

Published 8 Jan 2025The Falkland Islands Defense Force is a small organization independent of the British military, run directly by the Falkland Islands government. When it decided to update its small arms form the L1A1 SLR (aka British FAL) in the early 1990s, the British assumed they would purchase the new L85A1 rifles. However, by that time the flaws in the L85 were pretty well known, and the Islanders exercised their independence and chose to adopt something different. After investigating a number of different options they chose to use the Steyr AUG. At this time the AUG was in service with a number of other nations including the Australians and New Zealanders, and Steyr offered good terms and good support for the FIDF.

The FIDF purchased about 160 AUG rifles in total, including a small number of carbines and heavy-barreled LMGs. The carbines were particularly useful in a maritime role, which was part of the FIDF mission at the time (fisheries patrol). The LMG version, fitted with an Elcan C79 4x optic, was intended to supplant the FN MAG as a support weapon, but was found unfit for that role. Instead, most of the LMGs were converted to standard rifles via simple barrel swap. In addition, the Elcan optics proved prone to breakage, and were eventually replaced with British SUSATs. Indeed, some of the standard AUGs had their factory scopes replaced with SUSATs as well.

The AUG remained the standard rifle for the FIDF until recently, when the service received L85A3 rifles from the British. The AUG was not configured to use the bullet-trap blank adapters that the British used, and the L85s were intended to allow better integrated training between the two forces. A formal replacement for the AUG has not yet been determined, as it remains a bit unclear what the British military will decide to do to replace the L85 in the coming years.

Many thanks to the FIDF for giving me access to their armory to dig out these rifles to film for you! They remain today a small but quite well-equipped all-volunteer force dedicated to maintaining the security of the Falkland Islands.

(more…)

May 5, 2025

The Bloody Battle of Agincourt | Animated Episode

The Rest Is History

Published 30 Nov 2024“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers”.

The Battle of Agincourt in 1415 endures as perhaps the most totemic battle in the whole of English history. Thanks in part to Shakespeare’s masterful Henry V, the myths and legends of that bloody day echo across time, forever enshrining the young Henry as the greatest warrior king England had ever known. So too the enduring idea of the English as plucky underdogs, facing down unfavourable odds with brazen grit. And though the exact numbers of men who fought in the two armies is hotly contested, the prospect was certainly intimidating for the English host looking down upon the vast French force amassed below them the day before the battle. Hungry and weary after an unexpectedly long march, and demoralised by the number of French that would be taking to the field, the situation certainly seemed dire for the English. One man amongst them, however, held true to his belief that the day could still be won: Henry V. An undeniably brilliant military commander, he infused his men with a sense of patriotic mission, convincing them that theirs was truly a divinely ordained task, and therefore in this — and his careful strategic planning the night before the battle — he proves a striking case of one individual changing the course of history. However, the French too had plans in place for the day ahead: total warfare. In other words, to overwhelm the English in a single devastating moment of impact, sweeping the lethal Welsh archers aside. So it was that dawn broke on the 25th of October to the site of King Henry wearing a helmet surmounted by a glittering crown and bearing the emblems of both France and England, astride his little grey horse, and riding up and down his lines of weathered silver clad men, preparing them to stride into legend … then, as the French cavalry began their charge, the sky went black as 75,000 arrows blocked out the sun. What else would that apocalyptic day hold in store?

Join Tom and Dominic as they describe the epochal Battle of Agincourt. From the days building up to it, to the moment that the two armies shattered together in the rain and mud of France. It is a story of courage and cowardice, kings and peasants, blood and bowels, tragedy and triumph.

00:00 What is to come …

00:50 Shakespeare and Henry V

02:53 Agincourt is exceptional

04:15 The battle is a test of God’s favour

05:27 The English see the French forces …

09:30 The French aren’t offering battle

10:40 Why the French delay

11:13 The French think they’re going to win

11:35 An ominous silence

12:35 Henry’s plan

20:50 The French plan

24:28 How big were the armies

28:49 The lay of the land

34:50 Henry makes the first move

37:00 The French charge into darkness

38:57 The French army advances

45:50 Reaction to the slaughter

(more…)

May 1, 2025

Military Tactics In The Falklands

Pegasus Tests

Published 27 Dec 2024A discussion with Ian McCollum of Forgotten Weapons about Argentine and British tactics during the Falklands War.

#forgottenweapons

April 30, 2025

QotD: The experience of the infantryman through the ages

What about the other common difficulties of soldiering? How universal are those experiences: the bad food, long marches, heavy burdens and difficult labor and toil?

Well, here is where we come back to the note I made earlier about how “warring” and “soldiering” were different verbs with different meanings. After all, while soldiering implies these difficulties, warring doesn’t, necessarily. And it isn’t hard to see why – the warrior classes in these societies, often being aristocrats, generally didn’t do a lot of these things. It is, for instance, noted in the Roman sources when a general chose to eat the same food as his soldiers, because most Roman aristocrats didn’t when they served as generals or military tribunes. The privileges of rank and class applied.

And that’s something we see with medieval aristocrats too. On the one hand, Jean de Bueil talks about the “difficulties and travail” of war, but at the same time, Clifford Rogers notes one (fictional and lavish, but not outrageous) war party “suitable for a baron or banneret” included a chaplain, three heralds, four trumpeters, two drummers, four pages, two varlets (that is, servants for the pages), two cooks, a forager, a farrier, an armorer, twelve more serving men (with horses, presumably both as combatants and as servants), and a majordomo to manage them all – in addition to the one lord, three knights and nine esquires (C. Rogers, Soldiers’ Lives through History: the Middle Ages (2007), 28-9).

Jean le Bel (quoted in Rogers, op. cit.) contrasts the situation of the nobles in Edward III’s army (1327), where “one could see great nobility well served with a great plenty of dishes and sweets – such strange ones that I wouldn’t know to name or describe them. There one could see ladies richly adorned and nobly ornamented” while in the camp proper an open brawl between the regular soldiers from England and Hainault broke out and eventually turned into an open battle in which 316 died, but so segregated was the camp that, “most of the knights and of their masters were then at court, and knew nothing of this” (Rogers, 66-7). Likewise, except in fairly extreme positions, most of the ditch-digging, camp-building duties would fall to the common soldiers (and, as Roel Konijnendijk can quite accurately tell you, ditches are important! When in doubt, dig some ditches – or make others dig ditches for you).

That said, these differences are not merely confined to the high aristocrats. Marching under a heavy load is often given as one example of the quintessential “soldier experience”, but it seems that many Greek hoplites went to war with a personal slave or servant to carry their equipment for them, despite being infantrymen. The Romans carried equipment and supplies something closer to what a modern soldier might (both in terms of weight and also, apart from ammunition, in terms of what was carried), but then non-Roman sources like the Greek writer Polybius (18.18.1-7) or the Jewish writer Josephus (BJ 3.95) appear quite stunned with the amount of tools and equipment the Romans carry (and Polybius, by the by, is writing before Marius’ mules). Evidently the Roman impedementia was quite a bit heavier, though even the Macedonians carried much more than a Greek hoplite army (Note Engels, Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army, 1978 on this).

Meanwhile, Jonathan Roth is quick to note (in The Logistics of the Roman Army at War (264 B.C. – A.D. 235) (1999)) that despite either bad or insufficient rations being a common complaint of soldiers, such complaints appear absent from Roman sources, even in the context of legionary mutinies. Indeed, the evidence suggests that Roman soldiers ate quite well, with fairly ample rations. In camp the Roman soldier’s diet was not so different from what he might eat in peacetime (especially once we get into the imperial period with legions stationed in semi-permanent bases); on the march they had to make do with bucellatum, a hard biscuit something like hardtack. But for many Italian peasants, the diet doesn’t seem to have been much worse – or much different – from what they ate in peacetime.

By way of sharp contrast to the plodding, heavily loaded but surely very lethal Roman legionary, the impis of the Zulu traveled fast, light and sometimes somewhat hungry. Zulu warriors generally carried only their equipment on the march, while supplies were carried by udibi, boys serving as porters. Even then, such supplies were minimal – the Zulu force that arrived at Rorke’s Drift (1879) had only been out six days, but none of the warriors in it had eaten in two. Such minimally supplied flying columns, moving fast and with considerable stealth (one cannot read anything on the Anglo-Zulu war without noticing how, even with cavalry scouts, Zulu impis seem so often just to appear next to British forces) were the norm for Zulu warfare. And to be clear, this wasn’t some “primitive” or underdeveloped form of war – the light and fast operational movements of the Zulu were intentional (much of it was a product of Shaka’s reforms) and very effective – albeit not so effective as to offset the massive advantages the British possessed in population, economic capacity or military technology. Nevertheless, not even every sort of common soldier was the heavily loaded, slow moving, well-fed ditch-digging sort like the Romans. The “soldier experience” needs to cover the lightly loaded and armed, fast moving, hungry, non-ditch-digging Zulu experience too.

And then of course when we consider nomadic peoples, we find that in many cases their lives on campaign were not that much different from their lives at peacetime, involving many of the same skills and activities.

In short, the experience of the drudgery of war – the bad food, long toil, heavy encumbrance and so on was all still quite contingent (or we might say “dependent”) on the society going to war. Social divisions mattered. Expectations about masculine behavior mattered. Military systems mattered. Yes, modern armies in the European tradition expect their soldiers to do a lot of labor and drudgery, but remember where that military system came from: it was the system of the common soldiers serving under the aristocrats who most certainly did not do those things but who did impose sharp, corporal discipline. Which, to be clear, doesn’t make this system ineffective – it was clearly effective. The point here is that it was socially contingent – a different society would have come up with a different system. And they did! The Early Modern European system is only one way to organize an army and historically speaking not even the most common.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Universal Warrior, Part IIb: A Soldier’s Lot”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-02-05.

April 24, 2025

QotD: The Phalanx

… we need to distinguish what sort of phalanx because this is not the older hoplite phalanx in two very important ways: first, it is equipped and fights differently, but second it has a very different place in the overall tactical system: the Macedonian phalanx may be the “backbone” of a Hellenistic army, but it is not the decisive arm of the system.

So let’s start with the equipment, formation and fighting style. The older hoplite phalanx was a shield wall, using the large, c. 90cm diameter aspis and a one-handed thrusting spear, the dory. Only the front rank in a formation like this engaged the enemy, with the rear ranks providing replacements should the front hoplites fall as well as a morale force of cohesion by their presence which allowed the formation to hold up under the intense mental stress of combat. But while hoplites notionally covered each other with their shields, they were mostly engaged in what were basically a series of individual combats. As we noted with our bit on shield walls, the spacing here seems to have been wide enough that while the aspis of your neighbor is protecting you in that it occupies physical space that enemy weapons cannot pass through, you are not necessarily hunkered down shoulder-to-shoulder hiding behind your neighbor’s shield.

The Macedonian or sarisa-phalanx evolves out of this type of combat, but ends up quite different indeed. And this is the point where what should be a sentence or two is going to turn into a long section. The easy version of this section goes like this: the standard Macedonian phalangite (that is, the soldier in the phalanx) carried a sarisa, a two-handed, 5.8m long (about 19ft) pike, along with an aspis, a round shield of c. 75cm carried with an arm and neck strap, a sword as a backup weapon, a helmet and a tube-and-yoke cuirass, probably made out of textile. Officers, who stood in the first rank (the hegemones) wore heavier armor, probably consisting of either a muscle cuirass or a metal reinforced (that is, it has metal scales over parts of it) tube-and-yoke cuirass. I am actually quite confident that sentence is basically right, but I’m going to have to explain every part of it, because in popular treatments, many outdated reconstructions of all of this equipment survive which are wrong. Bear witness, for instance, to the Wikipedia article on the sarisa which gets nearly all of this wrong.

Wikipedia‘s article on the topic as of January, 2024. Let me point out the errors here.

1) The wrong wood, the correct wood is probably ash, not cornel – the one thing Connolly gets wrong on this weapon (but Sekunda, op. cit. gets right).

2) The wrong weight, entirely too heavy. The correct weight should be around 4kg, as Connolly shows.

3) Butt-spikes were not exclusively in bronze. The Vergina/Aigai spike is iron, though the Newcastle butt is bronze (but provenance, ????)

4) They could be anchored in the ground to stop cavalry. This pike is 5.8m long, its balance point (c. 1.6m from the back) held at waist height (c. 1m), so it would be angled up at something like 40 degrees, so anchoring the butt in the ground puts the head of the sarisa some 3.7m (12 feet) in the air – a might bit too high, I may suggest. The point could be brought down substantially if the man was kneeling, which might be workable. More to the point, the only source that suggests this is Lucian, a second century AD satirist (Dial Mort. 27), writing two centuries after this weapon and its formation had ceased to exist; skepticism is advised.

5) We’ll get to shield size, but assuming they all used the 60cm shield is wrong.

6) As noted, I don’t think these weapons were ever used in two parts joined by a tube and also the tube at Vergina/Aigai was in iron. Andronikos is really clear here, it is a talon en fer and a douille en fer. Not sure how that gets messed up.Sigh. So in detail we must go. Let us begin with the sarisa (or sarissa; Greek uses both spellings). This was the primary weapon of the phalanx, a long pike rather than the hoplite‘s one-handed spear (the dory). And we must discuss its structure, including length, because this is a case where a lot of the information in public-facing work on this is based on outdated scholarship, compounded by the fact that the initial reconstructions of the weapon, done by Minor Markle and Manolis Andronikos, were both entirely unworkable and, I think, quite clearly wrong. The key works to actually read are the articles by Peter Connolly and Nicholas Sekunda.1 If you are seeing things which are not working from Connolly and Sekunda, you may safely discard them.

Let’s start with length; one sees a very wide range of lengths for the sarisa, based in part on the ancient sources. Theophrastus (early third century BC) says it was 12 cubits long, Polybius (mid-second century) says it was 14 cubits, while Asclepiodotus (first century AD) says the shortest were 10 cubits, while Polyaenus (second century AD) says that the length was 16 cubits in the late fourth century.2 Two concerns come up immediately: the first is that the last two sources wrote long after no one was using this weapon and as a result are deeply suspect, whereas Theophrastus and Polybius saw it in use. However, the general progression of 12 to 14 to 16 – even though Polyaenus’ word on this point is almost worthless – has led to the suggestion that the sarisa got longer over time, often paired to notions that the Macedonian phalanx became less flexible. That naturally leads into the second question, “how much is a cubit?” which you will recall from our shield-wall article. Connolly, I think, has this clearly right: Polybius is using a military double-cubit that is arms-length (c. 417mm for a single cubit, 834mm for the double), while Theophrastus is certainly using the Athenian cubit (487mm), which means Theophrastus’ sarisa is 5.8m long and Polybius’ sarisa is … 5.8m long. The sarisa isn’t getting longer, these two fellows have given us the same measurement in slightly different units. This shaft is then tapered, thinner to the tip, thicker to the butt, to handle the weight; Connolly physically reconstructed these, armed a pike troupe with them, and had the weapon perform as described in the sources, which I why I am so definitively confident he is right. The end product is not the horribly heavy 6-8kg reconstructions of older scholars, but a manageable (but still quite heavy) c. 4kg weapon.

Of all of the things, the one thing we know for certain about the sarisa is that it worked.

Next are the metal components. Here the problem is that Manolis Andronikos, the archaeologist who discovered what remains our only complete set of sarisa-components in the Macedonian royal tombs at Vergina/Aigai managed to misidentify almost every single component (and then poor Minor Markle spent ages trying to figure out how to make the weapon work with the wrong bits in the wrong place; poor fellow). The tip of the weapon is actually tiny, an iron tip made with a hollow mid-ridge massing just 100g, because it is at the end of a very long lever and so must be very light, while the butt of the weapon is a large flanged iron butt (0.8-1.1kg) that provides a counter-weight. Finally, Andronikos proposed that a metal sleeve roughly 20cm in length might have been used to join two halves of wood, allowing the sarisa to be broken down for transport or storage; this subsequently gets reported as fact. But no ancient source reports this about the weapon and no ancient artwork shows a sarisa with a metal sleeve in the middle (and we have a decent amount of ancient artwork with sarisae in them), so I think not.3

Polybius is clear how the weapon was used, being held four cubits (c. 1.6m) from the rear (to provide balance), the points of the first five ranks could project beyond the front man, providing a lethal forward hedge of pike-points.4 As Connolly noted in his tests, while raised, you can maneuver quite well with this weapon, but once the tips are leveled down, the formation cannot readily turn, though it can advance. Connolly noted he was able to get a English Civil War re-enactment group, Sir Thomas Glemham’s Regiment of the Sealed Knot Society, not merely to do basic maneuvers but “after advancing in formation they broke into a run and charged”. This is not necessarily a laboriously slow formation – once the sarisae are leveled, it cannot turn, but it can move forward at speed.

The shield used by these formations is a modified form of the old hoplite aspis, a round, somewhat dished shield with a wooden core, generally faced in bronze.5 Whereas the hoplite aspis was around 90cm in diameter, the shield of the sarisa-phalanx was smaller. Greek tends to use two words for round shields, aspis and pelte, the former being bigger and the latter being smaller, but they shift over time in confusing ways, leading to mistakes like the one in the Wikipedia snippet above. In the classical period, the aspis was the large hoplite shield, while the pelte was the smaller shield of light, skirmishing troops (peltastai, “peltast troops”). In the Hellenistic period, it is clear that the shield of the sarisa-phalanx is called an “aspis” – these troops are leukaspides, chalkaspides, argyraspides (“white shields”, “bronze shields”, “silver shields” – note the aspides, pl. of aspis in there). This aspis is modestly smaller than the hoplite aspis, around 75cm or so in diameter; that’s still quite big, but not as big.

Then we have some elite units from this period which get called peltastai but have almost nothing to do with classical period peltastai. Those older peltasts were javelin-equipped light infantry skirmishers. But Hellenistic peltastai seem to be elite units within the phalanx who might carry the sarisa (but perhaps a shorter one) and use a smaller shield which gets called the pelte but is not the pelte of the classical period. Instead, it is built exactly like the Hellenistic aspis – complete with a strap-suspension system suspending it from the shoulder – but is smaller, only around 65cm in diameter. These sarisa-armed peltastai are a bit of a puzzle, though Asclepiodotus (1.2) in describing an ideal Hellenistic army notes that these guys are supposed to be heavier than “light” (psiloi) troops, but lighter than the main phalanx, carrying a smaller shield and a shorter sarisa, so we might understand them as an elite force of infantry perhaps intended to have a bit more mobility than the main body, but still be able to fight in a sarisa-phalanx. They may also have had less body-armor, contributing that the role as elite “medium” infantry with more mobility.6

Finally, our phalangites are armored, though how much and with what becomes really tricky, fast. We have an inscription from Amphipolis7 setting out military regulations for the Antigonid army which notes fines for failure to have the right equipment and requires officers (hegemones, these men would stand in the front rank in fighting formation) to wear either a thorax or a hemithorakion, and for regular soldiers where we might expect body armor, it specifies a kottybos. All of these words have tricky interpretations. A thorax is chest armor (literally just “a chest”), most often somewhat rigid armor like a muscle cuirass in bronze or a linothorax in textile (which we generally think means the tube-and-yoke cuirass), but the word is sometimes used of mail as well.8 A hemithorakion is clearly a half-thorax, but what that means is unclear; we have no ancient evidence for the kind of front-plate without back-plate configuration we get in the Middle Ages, so it probably isn’t that. And we just straight up don’t know what a kottybos is, although the etymology seems to suggest some sort of leather or textile object.9

In practice there are basically two working reconstructions out of that evidence. The “heavy” reconstruction10 assumes that what is meant by kottybos is a tube-and-yoke cuirass, and thus the thorax and hemithorakion must mean a muscle cuirass and a metal-reinforced tube-and-yoke cuirass respectively. So you have a metal-armored front line (but not entirely muscle cuirasses by any means) and a tube-and-yoke armored back set of ranks. I would argue the representational evidence tends to favor this; we most often see phalangites associated with tube-and-yoke cuirasses, rarely with muscle cuirasses (but sometimes!) and not often at all in situations where they have the rest of their battle kit (helmet, shield, sarisa) as required for the regular infantry by the inscription but no armor.

Then there is the “light” reconstruction11 which instead reads this to mean that only the front rank had any body armor at all and the back ranks only had what amounted to thick travel cloaks. Somewhat ironically, it would be really convenient for the arguments I make in scholarly venues if Sekunda was right about this … but I honestly don’t think he is. My judgment rebels against the notion that these formations were almost entirely unarmored and I think our other evidence cuts against it.12

Still, even if we take the “heavy” reconstruction here, when it comes to armor, we’re a touch less well armored compared to that older hoplite phalanx. The textile tube-and-yoke cuirass, as far as we can tell, was the cost-cutting “cheap” armor option for hoplites (as compared to more expensive bell- and later muscle-cuirasses in bronze). That actually dovetails with helmets: Hellenistic helmets are lighter and offer less coverage than Archaic and Classical helmets do as well. Now that’s by no means a light formation; the tube-and-yoke cuirass still offers good protection (though scholars currently differ on how to reconstruct it in terms of materials). But of course all of this makes sense: we don’t need to be as heavily armored, because we have our formation.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part Ia: Heirs of Alexander”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-01-19.

1. So to be clear, that means the useful is P. Connolly, “Experiments with the sarissa” JRMES 11 (2000) and N. Sekunda, “The Sarissa” Acta Universitatis Lodziensis 23 (2001). The parade of outdated scholarship is Andronikos, “Sarissa” BCH 94 (1970); M. Markle, “The Macedonian sarissa” AJA 81 (1977) and “Macedonian arms and tactics” in Macedonia and Greece in Late Classical and Early Hellenistic Times, (1982), P.A. Manti, “The sarissa of the Macedonian infantry” Ancient World 23.2 (1992) and “The Macedonian sarissa again” Ancient World 25.2 (1994), J.R. Mixter, “The length of the Macedonian sarissa” Ancient World 23.2 (1992). These weren’t, to be clear, bad articles, but they are stages of development in our understanding, which are now past.

2. Theophrastus HP 3.12.2. Polyb. 18.29.2. Asclepiodotus Tact. 5.1; Polyaenus Strat. 2.29.2. Also Leo Tact. 6.39 and Aelian Tact. 14.2 use Polybius’ figure, probably quoting him.

3. Also, what very great fool wants his primary weapon, which is – again – a 5.8m long pike that masses around 4kg to be held together in combat entirely by the tension and friction of a c. 20cm metal sleeve?

4. Christopher Matthew, op. cit., argues that Polybius must be wrong because if the weapon is gripped four cubits from the rear, it will foul the rank behind. I find this objection unconvincing because, as noted above and below, Peter Connolly did field drills with a pike troupe using the weapon and it worked. Also, we should be slow to doubt Polybius who probably saw the weapon and its fighting system first hand.

5. What follows is drawn from K. Liampi, Makedonische Schild (1998), which is the best sustained study of Hellenistic period shields.

6. Sekunda reconstructs them this way, without body armor, in Macedonian Armies after Alexander, (2013). I think that’s plausible, but not certain.

7. Greek text is in Hatzopoulos, op. cit.

8. Polyb. 30.25.2. Also of scale, Hdt. 9.22, Paus. 1.21.6.

9. The derivation assumed to be from κοσύμβη or κόσσυμβος, which are a sort of shepherd’s heavy cloak.

10. Favored by Hatzopoulos, Everson and Connolly.

11. Favored by Sekunda and older scholarship, as well as E. Borza, In the Shadow of Olympus (1990), 204-5, 298-9.

12. Representational evidence, but also the report that when Alexander got fresh armor for his army, he burned 25,000 sets of old, worn out armor. Curtius 9.3.21; Diodorus 17.95.4. Alexander does not have 25,000 hegemones, this must be the armor of the general soldiery and if he’s burning it, it must be made of organic materials. I think the correct reading here is that Alexander’s soldiers mostly wore textile tube-and-yoke cuirasses.

March 7, 2025

March 1, 2025

QotD: Roman Republic versus Seleucid Empire – the Battle of Magnesia

Rome’s successes at sea in turn set conditions for the Roman invasion of Anatolia, which will lead to the decisive battle at Magnesia, but of course in the midst of our naval narrative, we rolled over into a new year, which means new consuls. The Senate extended Glabrio’s command in Greece to finish the war with the Aetolians, but the war against Antiochus was assigned to Lucius Cornelius Scipio, one of the year’s consuls and brother of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, the victor over Hannibal at Zama (202). There’s an exciting bit of politics behind Scipio getting the assignment (including his famous brother promising to serve as one of his military tribunes), but in a sense that’s neither here nor there. As we’ve seen, Rome has no shortage of capable generals. From here on, if I say “Scipio”, I mean Lucius Cornelius Scipio; if I want his brother, I’ll say “Scipio Africanus”.

Scipio also brought fresh troops with him. The Senate authorized him to raise a supplementum (recruitment to fill out an army) of 3,000 Roman infantry, 100 Roman cavalry, 5,000 socii infantry and 200 socii cavalry (Livy 37.2.1) as well as authorizing him to carry the war into Asia (meaning Anatolia or Asia Minor) if he thought it wise – which of course he will. In addition to this, the two Scipios also called for volunteers from Scipio Africanus’ veterans and got 5,000 of them, a mix of Romans and socii (Livy 37.4.3), so all told Lucius Cornelius Scipio is crossing to Greece with reinforcements of some 13,000 infantry (including some battle-hardened veterans), 300 cavalry and one Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus.1 That said, a significant portion of this force is going to end up left in Greece to handle garrison duty and the Aetolians. Antiochus III, for his part, spends this time raising forces for a major battle, while dispatching his son Seleucus (the future Seleucus IV, r. 187-175) to try to raid Pergamum, Rome’s key ally in the region.

Once the Romans arrive (and join up with Eumenes’ army), both sides maneuvered to try and get a battle on favorable terms. Antiochus III’s army was massive with lots of cavalry – 62,000 infantry and 12,000 cavalry, an army on the same general order of magnitude as the one that fought at Raphia – so he sought an open area, setting up his fortified camp near Magnesia, with fairly formidable defenses – a ditch with a double-rampart (Livy 37.37.9-11). Unsurprisingly, the Romans, with a significant, but smaller force, preferred a fight in more confined quarters and for several days the armies sat opposite each other with minor skirmishes (Livy 37.38).

The problem Scipio faced was a simple one: the year was coming to a close, which meant that soon new consuls would be elected and he could hardly count on his command being extended. Consequently, Scipio calls together his war council – what the Romans call a consilium – to ask what he should do if Antiochus III couldn’t be lured into battle on favorable terms. The answer he got back was to force a battle and so force a battle Scipio did, advancing forward onto the ground of Antiochus’ choosing, leading to the Battle of Magnesia.

We have two accounts of this battle which mostly match up, one in Livy (Livy 37.39-44) and another in Appian’s Syrian Wars (App. Syr. 30-36). Livy here is generally the better source and chances are both authors are relying substantially on Polybius (who would be an even better source), whose account of the battle is lost.

Antiochus III’s army was enormous, with a substantial superiority in cavalry. From left to right, according to Livy (Livy 37.40), Antiochus III deployed: Cyrtian slinger and Elymaean archers (4,000), then a unit of caetrati (4,000; probably light infantry peltasts), then the contingent of Tralli (1,500; light infantry auxiliaries from Anatolia), then Carian and Cilicians equipped like Cretans (1,500; light archer infantry), then the Neo-Cretans (1,000; light archer infantry), then the Galatian cavalry (2,500; mailed shock cavalry), then a unit of Tarantine cavalry (number unclear, probably 500; Greek light cavalry), a part of the “royal squadron” of cavalry (1,000; Macedonian shock cavalry), then the ultra-heavy cataphract cavalry (3,000), supported by a mixed component of auxiliaries (2,700; medium thureophoroi infantry?) along with his scythed chariots and Arab camel troops.

That gets us to the central component of the line (still reading left to right): Cappadocians (2,000) who Livy notes were similarly armed to the Galatian infantry (1,500, unarmored, La Tène infantry kit, so “mediums”) who come next. Then the main force of the phalanx, 16,000 strong with 22 elephants. The phalanx was formed 32 ranks deep, with the intervals between the regiments covered by the elephants deployed in pairs, creating an articulated or enallax phalanx like Pyrrhus had, but using elephants rather than infantry to cover the “hinges”. This may in fact, rather than being a single phalanx 32 men deep be a “double” phalanx (one deployed behind the other) like we saw at Sellasia. Then on the right of the phalanx was another force of 1,500 Galatian infantry. Oddly missing here is the main contingent of the elite Silver Shields (the Argyraspides); some scholars2 note that a contingent of them 10,000 strong would make Livy’s total strength numbers and component numbers match up and he has just forgotten them in the main line. We might expect them to be deployed to the right of the main phalanx (where Livy will put the infantry Royal Cohort (regia cohors), confusing a subunit of the argyraspides with the larger whole unit. Michael Taylor in a forthcoming work3 has suggested they may also have been deployed behind the cavalry we’re about to get to or otherwise to their right.

That gets us now to the right wing (still moving left to right; you begin to realize how damn big this army is), we have more cataphracts (3,000, armored shock cavalry), the elite cavalry agema (1,000; elite Mede/Persian cavalry, probably shock), then Dahae horse archers (1,200; Steppe horse archers), then Cretan and Trallian light infantry (3,000), then some Mysian Archers (2,500) and finally another contingent of Cyrtian slinger and Elymaean archers (4,000).

This is, obviously, a really big army. But notice that a lot of its strength is in light infantry: combining the various archers, slingers and general light infantry (excluding troops we suspect to be “mediums”) we come to something like 21,500 lights, plus another 7,700 “medium” infantry and then 26,000 heavy infantry (accounting for the missing argyraspides). That’s 55,200 total, but Livy reports a total strength for the army of 62,000; it’s possible the missing remainder were troops kept back to defend the camp, in which case they too are likely light infantry. A Roman army’s infantry contingent is around 28% “lights” (the velites), who do not occupy any space in the main battle line. Antiochus’ infantry contingent, while massive, is 39% “lights” (and another 14% “mediums”), some of which do seem to occupy actual space in the battle line.

Of course Antiochus also has a massive amount of cavalry ranging from ultra-heavy cataphracts to light but highly skilled horse archers and massive cavalry superiority covereth a multitude of sins.

But the second problem with this gigantic army is one that – again, in a forthcoming work – Michael Taylor has pointed out. The physical space of the battlefield at Magnesia is not big enough to deploy the whole thing […]

Now Livy specifies that the flanks of Antiochus’ army curve forward, describing them as “horns” (cornu) rather than “wings” (alae) and noting they were “a little bit advanced” (paulum producto), which may be an effort to get more of this massive army actually into the fight […]. So while this army is large, it’s also unwieldy and difficult to bring properly into action and it’s not at all clear from either Livy or Appian that the whole army actually engaged – substantial portions of that gigantic mass of light infantry on the wings just seem to dissolve away once the battle begins, perhaps never getting into the fight in the first place.

The Roman force was deployed in its typical formation, with the three lines of the triplex acies and the socii flanking the legions (Livy 37.39.7-8), with the combined Roman and socii force being roughly 20,000 strong (the legions and alae being somewhat over-strength). In addition Eumenes, King of Pergamum was present and the Romans put his force on their right to cover the open flank, while he anchored his left flank on the Phrygios River. Eumenes’ wing consisted of 3,000 Achaeans (of the Achaean League) that Livy describes as caetrati and Appian describes as peltasts (so, lights), plus nearly all of Scipio’s cavalry: Eumenes’ cavalry guard of 800, plus another 2,200 Roman and socii cavalry, and than some auxiliary Cretan and Trallian light infantry, 500 each. Thinking his left wing, anchored on the river, relatively safe, Scipio posted only four turmae of cavalry there (120 cavalry). He also had a force of Macedonians and Thracians mixed together – so these are probably “medium” infantry – who had come as volunteers, who he posts to guard the camp rather than in the main battleline. I always find this striking, because I think a Hellenistic army would have put these guys in the front line, but a Roman commander looks at them and thinks “camp guards”. The Romans also had some war elephants, sixteen of them, but Scipio assesses that North African elephants won’t stand up to the larger Indian elephants of the Seleucids (which is true, they won’t) and so he puts them in reserve behind his lines rather than out front where they’d just be driven back into him. All told then, the Roman force is around 26,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry – badly outnumbered by Antiochus, but of a relatively higher average quality and a bit more capable of actually fitting its entire combat power into the space.

The Battle

Because the armies are so large, much like as happened at Raphia, the battle that results is almost three battles running in parallel: the two wings and the center. Antiochus III commanded from his right wing, where – contrary to the expectations of Scipio who thought the river would secure his flank there – he intended his main attack. His son Seleucus commanded the left. Livy reports a light rain which interfered with both with visibility and some of Antiochus’ light troops’ weapons, as their bows and slings reacted poorly to the moisture (as composite bows will sometimes do; Livy 37.41.3-4, note also App. Syr. 33).Antiochus opens the battle on his left with his scythed chariots, a novel “gimmick” weapon (heavy chariots with blades all over them, used to shock infantry out of position). This may have been a nasty surprise for the Romans, but given the dispositions of the army, it was Eumenes, not Scipio who faces the chariots and as Livy notes, Eumenes was well aware how to fight them (Livy 37.41.9), using his light troops – those Cretan archers and Trallian javelin-troops. Deployed in loose order, they were able to move aside to avoid the chariots better than heavy infantry in close-order (similar tactics are used against elephants) and could with their missiles strike at chariot drivers and horses at range (Livy 37.41.10-12). Turning back this initial attack seems to have badly undermined the morale of the Seleucid left-wing, parts of which fled, creating a gap between the extreme left-wing and the heavy cavalry contingent. Eumenes then, with the Roman cavalry, promptly hammered the disordered line, hitting first the camel troops, then in the confusion quickly overwhelming the rest of the cavalry, including the cataphracts, leading Antiochus’ left wing to almost totally collapse, isolating the phalanx in the center. It’s not clear what the large mass of light infantry on the extreme edge of the battlefield was doing.

Meanwhile on the other side of the battle, where Scipio had figured a light screen of 120 equites would be enough to hold the end of the line, Antiochus delivered is cavalry hammer-blow successfully. Obnoxiously, both of our sources are a lot less interested in describing how he does this (Livy 37.42.7-8 and App. Syr. 34), which is frustrating because it is a bit hard to make sense of how it turns out. On the one hand, the constricted battlefield will have meant that, regardless of how they were positioned, those argyraspides are going to end up following Antiochus’ big cavalry hammer on the (Seleucid) right. They then overwhelm the cavalry and put them to flight and then push the infantry of that wing (left ala of socii and evidently a good portion of the legion next to it) back to the Roman camp.

On the other hand, the Roman infantry line reaches its camp apparently in good order or something close to it. Marcus Aemilius, the tribune put in charge of the camp is able to rush out, reconstitute the infantry force and, along with the camp-guard, halt Antiochus’ advance. The thing is, infantry when broken by cavalry usually cannot reform like that, but the distance covered, while relatively short, also seems a bit too long for the standard legionary hastati-to-principes-to-triarii retrograde. Our sources (also including a passage of Justin, a much later source, 31.8.6) vary on exactly how precipitous the flight was and it is possible that it proceeded differently at different points, with some maniples collapsing and others making an orderly retrograde. In any case, it’s clear that the Roman left wing stabilized itself outside of the Roman camp, much to Antiochus’ dismay. Eumenes, having at this point realized both that he was winning on his flank and that the other flank was in trouble dispatched his brother Attalus with 200 cavalry to go aid the ailing Roman left wing; the arrival of these fellows seem to have caused panic and Antiochus at this point begins retreating.

Meanwhile, of course, there is the heavy infantry engagement at the center. Pressured and without flanking support, Appian reports that the Seleucid phalanx first admitted what light infantry remained and then formed square, presenting their pikes tetragonos, “on all four sides” (App. Syr. 35), a formation known as a plinthion in some Greek tactical manuals. Forming this way under pressure on a chaotic battlefield is frankly impressive (though if they were formed as a double-phalanx rather than a double-thick single-phalanx, that would have made it easier) and a reminder that the core of Antiochus’ army was quite capable. Unable in this formation to charge, the phalanx was showered with Roman pila and skirmished by Eumenes’ lighter cavalry; the Romans seem to have disposed of Antiochus’ elephants with relative ease – the Punic Wars had left the Romans very experienced at dealing with elephants (Livy 37.42.4-5). Appian notes that some of the elephants, driven back by the legion and maddened disrupted the Seleucid square, at which point the phalanx at last collapsed (App. Syr. 35); Livy has the collapse happen much faster, but Appian’s narrative here seems more plausible.

What was left of Antiochus’ army now fled to their camp – not far off, just like the Roman one – leading to a sharp battle at the camp which Livy describes as ingens et maior prope quam in acie cades, “a huge slaughter, almost greater than that in the battle” (Livy 37.43.10), with stiff resistance at the camp’s gates and walls holding up the Romans before they eventually broke through and butchered the survivors. Livy reports that of Antiochus’ forces, 50,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry were killed, another 1,500 captured; these seem really high as figures go, but Appian reports almost the exact same. Interesting, Livy doesn’t report the figure in his own right or attribute it to Polybius but instead simply notes “it is said that”, suggesting he may not be fully confident of the number either. Taylor supposes, reasonably I think, that this oversized figure may also count men who fled from the battlefield, reflecting instead that once Antiochus III could actually reconstitute his army, he had about 19,000 men, most of the rest having fled.4 Either way, the resulting peace makes clear that the Seleucid army was shattered beyond immediate repair.

Roman losses, by contrast, were shockingly light. Livy reports 300 infantry lost, 24 Roman cavalry and 25 out of Eumenes’ force; Appian adds that the 300 infantry were “from the city” – meaning Roman citizens – so some socii casualties have evidently been left out (but he trims Eumenes’ losses down to just fifteen cavalry) (Livy 37.44.2-3; App. Syr. 36). Livy in addition notes that many Romans were wounded in addition to the 300 killed. This is an odd quirk of Livy’s casualty reports for Roman armies against Hellenistic armies and I suspect it reflects the relatively high effectiveness of Roman body armor, by this point increasingly dominated by the mail lorica hamata: good armor converts lethal blows into survivable wounds.5 It also fits into a broader pattern we’ve seen: Hellenistic armies that face Roman armies always take heavy casualties, winning or losing, but when Roman armies win they tend to win lopsidedly. It is a trend that will continue.

So why Roman victory at Magnesia? It is certainly not the case that the Romans had the advantage of rough terrain in the battle: the battlefield here is flat and fairly open. It should have been ideal terrain for a Hellenistic army.

A good deal of the credit has to go to Eumenes, which makes the battle a bit hard to extrapolate from. It certainly seems like Eumenes’ quick thinking to disperse the Seleucid chariots and then immediately follow up with his own charge was decisive on his flank, though not quite battle winning. Eumenes’ forces, after all, lacked the punch to disperse the heavier phalanx, which did not panic when its wing collapsed. Instead, the Seleucid phalanx, pinned into a stationary, defensive position by Eumenes’ encircling cavalry, appears to have been disassembled primary by the Roman heavy infantry, peppering it with pila before inducing panic into the elephants. It turns out that Samnites make better “glue” for an articulated phalanx than elephants, because they are less likely to panic.

Meanwhile on the Seleucid right (the Roman left), the flexible and modular nature of the legion seems to have been a major factor. Antiochus clearly broke through the Roman line at points, but with the Roman legion’s plethora of officers (centurions, military tribunes, praefecti) and with each maniple having its own set of standards to rally around, it seems like the legion and its socii ala managed to hold together and eventually drive Antiochus off, despite being pressured. That, in and of itself, is impressive: it is the thing the Seleucid center fails to do, after all.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part IVb: Antiochus III”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-04-05.

1. I enjoy this joke because the idea of bringing Scipio Africanus along as a junior officer is amusing, but I should note that in the event, he doesn’t seem to have had much of a role in the campaign.

2. E.g. Bar Kockva, The Seleucid Army: Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns (1979)

3. “A Commander Will Put an End to his Insolence: the Battle of Magnesia, 190BC” to appear in The Seleucids at War: Recruitment, Organization and Battles (forthcoming in 2024), eds. Altay Coşkun and Benhamin E. Scolnic.

4. Taylor, Antiochus the Great (2013), 143.

5. On this, see, uh, me, “The Adoption and Impact of Roman Mail Armor in the Third and Second Centuries B.C.” Chiron 52 (2022).

February 23, 2025

QotD: The Hellenistic army system as a whole

I should note here at the outset that we’re not going to be quite done with the system here – when we start looking at the third and second century battle record, we’re going to come back to the system to look at some innovations we see in that period (particularly the deployment of an enallax or “articulated” phalanx). But we should see the normal function of the components first.

No battle is a perfect “model” battle, but the Battle of Raphia (217BC) is handy for this because we have the two most powerful Hellenistic states (the Ptolemies and Seleucids) both bringing their A-game with very large field armies and deploying in a fairly standard pattern. That said, there are some quirks to note immediately: Raphia is our only really good order of battle of the Ptolemies, but as our sources note there is an oddity here, specifically the mass deployment of Egyptians in the phalanx. As I noted last time, there had always been some ethnic Egyptians (legal “Persians”) in the phalanx, but the scale here is new. In addition, as we’ll see, the position of Ptolemy IV himself is odd, on the left wing matched directly against Antiochus III, rather than on his own right wing as would have been normal. But this is mostly a fairly normal setup and Polybius gives us a passably good description (better for Ptolemy than Antiochus, much like the battle itself).

We can start with the Seleucid Army and the tactical intent of the layout is immediately understandable. Antiochus III is modestly outnumbered – he is, after all, operating far from home at the southern end of the Levant (Raphia is modern-day Rafah at the southern end of Gaza), and so is more limited in the force he can bring. His best bet is to make his cavalry and elephant superiority count and that means a victory on one of the wings – the right wing being the standard choice. So Antiochus stacks up a 4,000 heavy cavalry hammer on his flank behind 60 elephants – Polybius doesn’t break down which cavalry, but we can assume that the 2,000 with Antiochus on the extreme right flank are probably the cavalry agema and the Companions, deployed around the king, supported by another 2,000 probably Macedonian heavy cavalry. He then uses his Greek mercenary infantry (probably thureophoroi or perhaps some are thorakitai) to connect that force to the phalanx, supported by his best light skirmish infantry: Cretans and a mix of tough hill folks from Cilicia and Caramania (S. Central Iran) and the Dahae (a steppe people from around the Caspian Sea).

His left wing, in turn, seems to be much lighter and mostly Iranian in character apart from the large detachment of Arab auxiliaries, with 2,000 more cavalry (perhaps lighter Persian-style cavalry?) holding the flank. This is a clearly weaker force, intended to stall on its wing while Antiochus wins to the battle on the right. And of course in the middle [is] the Seleucid phalanx, which was quite capable, but here is badly outnumbered both because of how full-out Ptolemy IV has gone in recruiting for his “Macedonian” phalanx and also because of the massive infusion of Egyptians.

But note the theory of victory Antiochus III has: he is going to initiate the battle on his right, while not advancing his left at all (so as to give them an easier time stalling), and hope to win decisively on the right before his left comes under strain. This is, at most, a modest alteration of Alexander-Battle.

Meanwhile, Ptolemy IV seems to have anticipated exactly this plan and is trying to counter it. He’s stacked his left rather than his right with his best troops, including his elite infantry (the agema and peltasts, who, while lighter, are more elite) and his best cavalry, supported by his best (and only) light infantry, the Cretans.1 Interestingly, Polybius notes that Echecrates, Ptolemy’s right-wing commander waits to see the outcome of the fight on the far side of the army (Polyb. 6.85.1) which I find odd and suggests to me Ptolemy still carried some hope of actually winning on the left (which was not to be). In any case, Echecrates, realizing that sure isn’t happening, assaults the Seleucid left.

I think the theory of victory for Ptolemy is somewhat unconventional: hold back Antiochus’ decisive initial cavalry attack and then win by dint of having more and heavier infantry. Indeed, once things on the Ptolemaic right wing go bad, Ptolemy moves to the center and pushes his phalanx forward to salvage the battle, and doing that in the chaos of battle suggests to me he always thought that the matter might be decided that way.

In the event, for those unfamiliar with the battle: Antiochus III’s right wing crumples the Ptolemaic left wing, but then begins pursuing them off of the battlefield (a mistake he will repeat at Magnesia in 190). On the other side, the Gauls and Thracians occupy the front face of the Seleucid force while the Greek and Mercenary cavalry get around the side of the Seleucid cavalry there and then the Seleucid left begins rolling up, with the Greek mercenary infantry hitting the Arab and Persian formations and beating them back. Finally, Ptolemy, having escaped the catastrophe on his left wing, shows up in the center and drives his phalanx forward, where it wins for what seem like obvious reasons against an isolated Seleucid phalanx it outnumbers almost 2-to-1.

But there are a few structural features I want to note here. First, flanking this army is really hard. On the one hand, these armies are massive and so simply getting around the side of them is going to be difficult (if they’re not anchored on rivers, mountains or other barriers, as they often are). Unlike a Total War game, the edge of the army isn’t a short 15-second gallop from the center, but likely to be something like a mile (or more!) away. Moreover, you have a lot of troops covering the flanks of the main phalanx. That results, in this case, in a situation where despite both wings having decisive actions, the two phalanxes seem to be largely intact when they finally meet (note that it isn’t necessarily that they’re slow; they seem to have been kept on “stand by” until Ptolemy shows up in the center and orders a charge). If your plan is to flank this army, you need to pick a flank and stack a ton of extra combat power there, and then find a way to hold the center long enough for it to matter.

Second, this army is actually quite resistive to Alexander-Battle: if you tried to run the Issus or Gaugamela playbook on one of these armies, you’d probably lose. Sure, placing Alexander’s Companion Cavalry between the Ptolemaic thureophoroi and Gallic mercenaries (about where he’d normally go) would have him slam into the Persian and Medean light infantry and probably break through. But that would be happening at the same time as Antiochus’ massive 4,000-horse, 60-elephant hammer demolished Ptolemaic-Alexander’s left flank and moments before the 2,000 cavalry left-wing struck Alexander himself in his flank as he advanced. The Ptolemaic army is actually an even worse problem, because its infantry wings are heavier, making that key initial cavalry breakthrough harder to achieve. Those chunky heavy-cavalry wings ensure that an effort to break through at the juncture of the center and the wing is foolhardy precisely because it leaves the breakthrough force with heavy cavalry to one side and heavy infantry to the other.

I know this is going to cause howls of pain and confusion, but I do not think Alexander could have reliably beaten either army deployed at Raphia; with a bit of luck, perhaps, but on the regular? No. Not only because he’d be badly outnumbered (Alexander’s army at Gaugamela is only 40,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry) but because these armies were adapted to precisely the sort of army he’d have and the tactics he’d use. Even without the elephants (and elephants gave Alexander a hell of a time at the Hydaspes), these armies can match Alexander’s heavy infantry core punch-for-punch while having enough force to smash at least one of his flanks, probably quite quickly. Note that the Seleucid Army – the smaller one at Raphia – has almost exactly as much heavy infantry at Raphia as Alexander at Gaugamela (30,000 to 31,000), and close to as much cavalry (6,000 to 7,000), but of course also has a hundred and two elephants, another 5,000 more “medium” infantry and massive superiority in light infantry (27,000 to 9,000). Darius III may have had no good answer to the Macedonian phalanx, but Antiochus III has a Macedonian phalanx and then essentially an entire second Persian-style army besides (and his army at Magnesia is actually more powerful than his army at Raphia).

This is not a degraded form of Alexander’s army, but a pretty fearsome creature of its own, which supplements an Alexander-style core with larger amounts of light and medium troops (and elephants), without sacrificing much, if any, in terms of heavy infantry and cavalry. The tactics are modest adjustments to Alexander-Battle which adapt the military system for symmetrical engagements against peer armies. The Hellenistic Army is a hard nut to crack, which is why the kingdoms that used them were so successful during the third century, to the point that, until the Romans show up, just about the only thing which could beat a Hellenistic army was another Hellenistic army.