Drachinifel

Published 5 Sept 2025Today we take a look at a heretofore unpublished account from a sailor who saw the destruction of HMS Hood, and take a look at what this might tell us about the incident.

(more…)

September 6, 2025

New Evidence on the loss of HMS Hood!

April 2, 2025

Iceland’s “double standards about sex between adults and minors … exposes grey areas in victim-centered sanctimony”

Janice Fiamengo discusses the recent revelation that Iceland’s Minister for Education and Children’s Affairs, Ásthildur Lóa Thórsdóttir, had an affair with an under-age teen when she was in her 20s:

Last week, Ásthildur Lóa Thórsdóttir [right], Iceland’s Minister for Education and Children’s Affairs, was revealed to have had a sexual relationship with a teen boy decades ago, when she was 23 years old. The case vividly highlights the west’s double standards about sex between adults and minors, and it exposes grey areas in victim-centered sanctimony.

That the case occurred in Iceland, a feminist stronghold with a female president, a female prime minister, and a claimed “zero-tolerance policy for sexual abuse and exploitation of children“, is not at all surprising. No one seriously expects feminists to apply their touted compassion to male teenagers; and no one believes that their championing of gender equality includes sexual probity for women.

Iceland is so thoroughly feminist that in 2023, the prime minister herself joined other women on a one-day strike to demand, amongst other utopian objectives, “an end to unequal pay,” neatly sidestepping (while illustrating) that the so-called pay gap is caused primarily by women’s tendency to work fewer hours than men do. Female moral innocence is such a cherished belief of the Nordic island nation that it has designated 2025 as Women’s Year, with “12 months of events dedicated to progressing gender equality.” (Interested readers should consult a gushing Guardian article, “Women are the best to women“, which depicts Iceland as a near-idyllic women-led community in which men hardly figure.)

Clearly, when the most powerful woman in the country can take a day off to showcase women’s alleged lack of power, few women are prepared to consider their own potential abuse of it.

That brings us to the Minister for Children’s Affairs, who appeared flabbergasted last week to find that her long-ago sexual past has become fodder for unsympathetic public discussion and suggestions of serious impropriety. “I understand … what it looks like“, she is quoted as saying to reporters, seemingly exasperated at how difficult it is “to get the right story in the news today”. At 58 years of age, Thórsdóttir is being given a tiny glimpse into what thousands of men have experienced since feminism entered its Jacobin phase.

Over three decades ago, Thórsdóttir began a relationship with a 15-year-old boy who was attending her church group. He has been identified as Eirik Asmundsson. He was a troubled boy with a chaotic home life, and she was an adult member in the group; newspaper articles have said that she was a group counselor, which she denies. She claims that the relationship did not become sexual until the boy was 16, and that he pursued her.

Thórsdóttir eventually gave birth to a child — a son — when she was 23 and Asmundsson was 16. She claims, again contrary to news reports, that their sexual relationship was long over by then, having lasted only a few weeks. What is undisputed is that she forced the boy to pay child support for 18 years, long after she had met and married another man, which occurred about a year after the child’s birth. She also opposed numerous requests by her child’s father to form and maintain a relationship with his son. Overall, she treated the boy shamefully.

Naturally, if a male government minister had been found to have been sexually involved with, impregnated, and then split from a 15- or 16-year-old girl when he was 22, especially when he was part of a religious organization in which he had some degree of moral or spiritual influence over her, there would be no public doubt whatsoever about his culpability.

All news reports would have been condemnatory, and his protestations, if he had been naïve enough to make any, would have been in vain. There would have been a chorus of disapproving statements from his fellow politicians in the Icelandic parliament. He would have been forced to resign from government and would likely be facing criminal investigation, perhaps for custodial rape (sex with a youth in one’s employment, care, or custody).

In Thórsdóttir’s case, in contrast, there has been only a brief flurry of reports and limited personal fallout. She was forced to resign from her ministerial post, but she remains in government. That she has kept her job is extraordinary. The Daily Mail, while not defending her, waffled about her potential criminality, saying “The age of consent is 15 in Iceland, but it is illegal to have sex with anyone under the age of 18 if the adult holds a position of authority over them, as Thorsdottir is accused of doing“.

February 2, 2025

HMS Hood – Death in 17 Mins – The Bismarck Part 2

World War Two

Published 1 Feb 2025On May 24, 1941, the Kriegsmarine‘s mighty battleship Bismarck goes head to head with the Royal Navy’s HMS Hood. Seventeen minutes later, just one of the steel titans is left afloat and 1,400 men are dead.

Special thanks goes to the HMS Hood Association, to learn more about HMS hood visit hmshood.org.uk

(more…)

January 27, 2025

The Bismarck‘s First Adventure – The Bismarck Part 1

World War Two

Published 26 Jan 2025At 02:00 on May 19, 1941, Germany’s most powerful battleship ever sets sail. Bismarck will sail out into the North Atlantic, evade the Royal Navy and tear apart Britain’s Atlantic convoys. At least that’s the plan … pretty soon things start to go wrong.

(more…)

December 26, 2023

The awe-inducing power of volcanoes

Ed West considers just how much human history has been shaped by vulcanology, including one near-extinction event for the human race:

A huge volcano has erupted in Iceland and it looks fairly awesome, both in the traditional and American teenager senses of the word.

Many will remember their holidays being ruined 13 years ago by the explosion of another Icelandic volcano with the epic Norse name Eyjafjallajökull. While this one will apparently not be so disruptive, volcano eruptions are an under-appreciated factor in human history and their indirect consequences are often huge.

Around 75,000 years ago an eruption on Toba was so catastrophic as to reduce the global human population to just 4,000, with 500 women of childbearing age, according to Niall Ferguson. Kyle Harper put the number at 10,000, following an event that brought a “millennium of winter” and a bottleneck in the human population.

In his brilliant but rather depressing The Fate of Rome, Harper looked at the role of volcanoes in hastening the end of antiquity, reflecting that “With good reason, the ancients revered the fearsome goddess Fortuna, out of a sense that the sovereign powers of this world were ultimately capricious”.

Rome’s peak coincided with a period of especially clement climatic conditions in the Mediterranean, in part because of the lack of volcanic activity. Of the 20 largest volcanic eruptions of the last 2,500 years, “none fall between the death of Julius Caesar and the year AD 169”, although the most famous, the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, did. (Even today it continues to reveal knowledge about the ancient world, including a potential treasure of information.)

However, the later years of Antiquity were marked by “a spasm” of eruptions and as Harper wrote, “The AD 530s and 540s stand out against the entire late Holocene as a moment of unparalleled volcanic violence”.

In the Chinese chronicle Nan Shi (“The History of the Southern Dynasties”) it was reported in February 535 that “there twice was the sound of thunder” heard. Most likely this was a gigantic volcanic explosion in the faraway South Pacific, an event which had an immense impact around the world.

Vast numbers died following the volcanic winter that followed, with the year 536 the coldest of the last two millennia. Average summer temperature in Europe fell by 2.5 degrees, and the decade that followed was intensely cold, with the period of frigid weather lasting until the 680s.

The Byzantine historian Procopius wrote how “during the whole year the sun gave forth its light without brightness … It seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear”. Statesman Flavius Cassiodorus wrote how: “We marvel to see now shadow on our bodies at noon, to feel the mighty vigour of the sun’s heat wasted into feebleness”.

A second great volcanic eruption followed in 540 and (perhaps) a third in 547. This led to famine in Europe and China, the possible destruction of a city in Central America, and the migration of Mongolian tribes west. Then, just to top off what was already turning out to be a bad decade, the bubonic plague arrived, hitting Constantinople in 542, spreading west and reaching Britain by 544.

Combined with the Justinian Plague, the long winter hugely weakened the eastern Roman Empire, the combination of climatic disaster and plague leading to a spiritual and demographic crisis that paved the way for the rise of Islam. In the west the results were catastrophic, and urban centres vanished across the once heavily settled region of southern Gaul. Like in the Near East, the fall of civilisation opened the way for former barbarians to build anew, and “in the Frankish north, the seeds of a medieval order germinated. It was here that a new civilization started to grow, one not haunted by the incubus of plague”.

November 9, 2023

Defending a stateless society: the Estonian way

David Friedman responded to a criticism of his views from Brad DeLong. Unfortunately, the criticism was written about a decade before David saw it, so he posted his response on his own Substack instead:

English version of the Estonian Defence League’s home page as of 2023-11-08.

https://www.kaitseliit.ee/en

Back in 2013 I came across a piece by Brad DeLong critical of my views. It argued that there were good reasons why anarcho-capitalist ideas did not appear until the nineteenth century, reasons illustrated by how badly a stateless society had worked in the Highlands of Scotland in the 17th century. I wrote a response and posted it to his blog, then waited for it to appear.

I eventually discovered what I should have realized earlier — that his post had been made nine years earlier. It is not surprising that my comment did not appear. The issues are no less interesting now than they were then, so here is my response:

Your argument rejecting a stateless order on the evidence of the Scottish Highlands is no more convincing than would be a similar argument claiming that Nazi Germany or Pol Pot’s Cambodia shows how bad a society where law is enforced by the state must be. The existence of societies without state law enforcement that work badly — I do not know enough about the Scottish Highlands to judge how accurate your account is — is no more evidence against anarchy than the existence of societies with state law enforcement that work badly is against the alternative to anarchy.

To make your case, you have to show that societies without state law enforcement have consistently worked worse than otherwise similar societies with it. For a little evidence against that claim I offer the contrast between Iceland and Norway in the tenth and eleventh centuries or northern Somalia pre-1960 when, despite some intervention by the British, it was in essence a stateless society, and the situation in the same areas after the British and Italians set up the nation of Somalia, imposing a nation state on a stateless society. You can find short accounts of both those cases, as well as references and a more general discussion of historical feud societies, in my Legal Systems Very Different From Ours. A late draft is webbed.

So far as the claim that the idea of societies where law enforcement is private is a recent invention, that is almost the opposite of the truth. The nation state as we know it today is a relatively recent development. For historical evidence, I recommend Seeing Like a State by James Scott, who offers a perceptive account of the ways in which societies had to be changed in order that states could rule them.

As best I can tell, most existing legal systems developed out of systems where law enforcement was private — whether, as you would presumably argue, improving on those systems or not is hard to tell. That is clearly true of, at least, Anglo-American common law, Jewish law and Islamic law, and I think Roman law as well. For details again see my book.

In which context, I am curious as to whether you regard yourself as a believer in the Whig theory of history, which views it as a story of continual progress, implying that “institutions A were replaced by institutions B” can be taken as clear evidence of the superiority of the latter.

And From the Real World

In chapter 56 of the third edition of The Machinery of Freedom I discussed how a stateless society might defend against an aggressive state, which I regard as the hardest problem for such a society. One of the possibilities I raise is having people voluntarily train and equip themselves for warfare for the fun (and patriotism) of it, as people now engage in paintball, medieval combat in the Society for Creative Anachronism, and various other military hobbies.

A correspondent sent me a real world example of that approach — the Estonian Defense League, civilian volunteers trained in the skills of insurgency. They refer to it as “military sport”. Competitions almost every week.

Estonia’s army of 6000 would not have much chance against a Russian invasion but the Estonians believe, with the examples of Iraq and Afghanistan in mind, that a large number of trained and armed insurgents could make an invasion expensive. The underlying principle, reflected in a Poul Anderson science fiction story1 and one of my small collection of economics jokes,2 is that to stop someone from doing something you do not have to make it impossible, just unprofitable. You can leverage his rationality.

Estonia has a population of 1.3 million. The league has 16,000 volunteers. Scale the number up to the population of the U.S. and you get a militia of about four million, roughly twice the manpower of the U.S. armed forces, active and reserve combined. The League is considered within the area of government of the Ministry of Defense, which presumably provides its weaponry; in an anarchist equivalent the volunteers would have to provide their own or get them by voluntary donation. But the largest cost, the labor, would be free.

Switzerland has a much larger military, staffed by universal compulsory service, but there are also private military associations that conduct voluntary training in between required military drills. Members pay a small fee that helps fund the association and use their issued arms and equipment for the drills.

1. The story is “Margin of Profit“. I discuss it in an essay for a work in progress, a book or web page containing works of short literature with interesting economics in them.

2. Two men encountered a hungry bear. One turned to run. “It’s hopeless,” the other told him, “you can’t outrun a bear.” “No,” he replied, “But I might be able to outrun you.”

September 7, 2023

History Summarized: Iceland’s Hallgrimskirkja

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 26 May 2023The name is more visually complicated than the church itself.

I tried my best to pronounce all the Icelandic correctly but that LL sound is TRICKY.SOURCES & Further Reading:

Great Courses lectures “Iceland’s Independence” and “The Capital and Beyond in Southwest Iceland” from The Great Tours Iceland by Jennifer Verdolin, “Iceland’s Hallgrimskirkja” from World’s Greatest Churches by William R. Cook. Plus, two visits to Iceland and a lot of time spent staring at the thing.

(more…)

June 16, 2023

October 10, 2021

Three Years in Vinland: The Norse Attempt to Colonize America

Atun-Shei Films

Published 9 Oct 2021Happy Leif Erikson Day! Some time after Thorvald Erikson’s disastrous voyage to the mysterious lands west of Greenland, a wealthy Icelander named Thorfinn Karlsefni financed and led an expedition of his own, with the goal of establishing a permanent Norse settlement in Vinland. Karlsefni and his crew would spend three summers in the New World, where they would have to deal with internal division, hostile Native Americans, and (according to some) the wrath of demonic mythological creatures.

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

Leave a Tip via Paypal ► https://www.paypal.me/atunsheifilms

Buy Merch ► https://teespring.com/stores/atun-she…

#LeifErikson #Vinland #History

Original Music by Dillon DeRosa ► http://dillonderosa.com/

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/atun_shei~REFERENCES~

[1] Magnus Magnusson & Hermann Pálsson. The Vinland Sagas: The Norse Discovery of America (1965). Penguin Books, Page 7-43

[2] Birgitta Wallace. “Karlsefni” (2006). The Canadian Encyclopedia [https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.c..].

[3] Lorraine Boissonault. “L’Anse Aux Meadows and the Viking Discovery of North America” (2005). JSTOR Daily https://daily.jstor.org/anse-aux-mead…

May 23, 2021

Where is Scandinavia?

CGP Grey

Published 25 Mar 2015Grey Merch: https://cgpgrey.com/merch

Grey on Twitter: https://twitter.com/cgpgrey

October 27, 2020

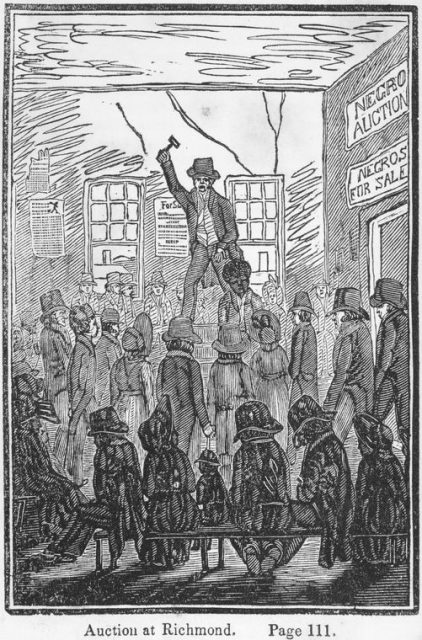

America’s “brutal system of slavery [was] unlike anything that had existed in the world before”

I missed this article by Kay S. Hymowitz when it was published by City Journal a couple of weeks back:

Auction at Richmond. (1834)

“Five hundred thousand strokes for freedom ; a series of anti-slavery tracts, of which half a million are now first issued by the friends of the Negro.” by Armistead, Wilson, 1819?-1868 and “Picture of slavery in the United States of America. ” by Bourne, George, 1780-1845

New York Public Library via Wikimedia Commons.

… slavery was a mundane fact in most human civilizations, neither questioned nor much thought about. It appeared in the earliest settlements of Sumer, Babylonia, China, and Egypt, and it continues in many parts of the world to this day. Far from grappling with whether slavery should be legal, the code of Hammurabi, civilization’s first known legal text, simply defines appropriate punishments for recalcitrant slaves (cutting off their ears) or those who help them escape (death). Both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament take for granted the existence of slaves. Slavery was so firmly established in ancient Greece that Plato could not imagine his ideal Republic without them, though he rejected the idea of individual ownership in favor of state control. As for Rome, well, Spartacus, anyone?

In the ancient world, slaves were almost always captives from the era’s endless wars of conquest. They were forced to do all the heavy labor required for building and sustaining cities and towns: clearing forests; building roads, temples, and palaces; digging and transporting stone; hoeing fields; rowing galley ships; and marching to almost-certain death in the front line of battle. Women (and often enough boy) slaves had the task of servicing the sexual appetites of their masters. None of that changed with the arrival of a new millennium. Gaelic tribes took advantage of the fall of the Roman Empire to raid the west coast of England and Wales for strong bodies; one belonged to a 16-year-old later anointed St. Patrick, patron saint of Ireland. “In the slavery business, no tribe was fiercer or more feared than the Irish,” writes Thomas Cahill in How the Irish Saved Civilization.

Today, of course, the immorality of slave-owning is as clear as day. But in the premodern world, no neat division existed between evil slaveowners and their innocent victims. Once the Vikings arrived in their longboats in the 700s, the Irish enslavers found themselves the enslaved. Slavery became the commanding height of the Viking economy; Norsemen raided coastal villages across Europe and brought their captives to Dublin, which became one of the largest slave markets of the time. The Vikings thought of their slaves as more like cattle than people; the unlucky victims had to sleep alongside the domestic animals, according to the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen. Norsemen rounded up captured Irish men and women to settle the desolate landscape of Iceland; scientists have found Irish DNA in present-day Icelanders, a legacy of that time. The Slavic tribes in Eastern Europe were an especially fertile supplier for Viking slave traders as well as for Muslim dealers from Spain: their Latin name gave us the word slave. Slavs were evidently not deterred by the misery they must have suffered; when Viking power waned by the twelfth century, the Slavs turned around and enslaved Vikings as well as Greeks.

Slavery was a normal state of affairs well beyond the territory we now call Europe. The Mayans had slaves; the Aztecs harnessed the labor of captives to build their temples and then serve as human sacrifices at the altars they had helped construct. The ancient Near East and Asia Minor were chockfull of slaves, mostly from East Africa. According to eminent slavery scholar Orlando Patterson, East Africa was plundered for human chattel as far back as 1580 BC. Muhammad called for compassion for the enslaved, but that didn’t stop his followers from expanding their search for chattel beyond the east coast into the interior of Africa, where the trade flourished for many centuries before those first West Africans arrived in Jamestown. Throughout that time, African kings and merchants grew rich from capturing and selling the millions of African slaves sent through the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean to Persians and Ottomans.

From the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries, the North African Barbary coast was a hub for “white slavery.” This episode was relatively short-lived in the global history of slavery, but one with overlooked impact on Western culture. Around 1619, just as the first Africans were being sailed from the African coast to Jamestown, Algerian and Tunisian pirates, or “corsairs” as they were known, were using their boats to raid seaside villages on the Mediterranean and Atlantic for slaves who happened in this case to be white. In 1631, Ottoman pirates sacked Baltimore on the southern coast of Ireland, capturing and enslaving the villagers. Around the same time, Iceland was raided by Barbary corsairs who took hundreds of prisoners, selling them into lifetime bondage.

October 26, 2020

October 10, 2020

When Vikings Met Native Americans: The Voyage of Thorvald Erikson

Atun-Shei Films

Published 9 Oct 2020Happy Leif Erikson Day! After Leif’s discovery of unknown lands to the west of Greenland, his brother Thorvald set off on an expedition of his own. Thorvald’s voyage, as related in the medieval Icelandic text The Saga of the Greenlanders, marks the first time in recorded history that Europeans came face-to-face with Native Americans. In this video, I regale you with this tale of adventure, exploration, and cultural collision. And for some reason, I spend about a third of the video talking about a bowl, a coin, and some yarn made of goat hair.

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

Leave a Tip via Paypal ► https://www.paypal.me/atunsheifilms (All donations made here will go toward the production of The Sudbury Devil, our historical feature film)

Buy Merch ► teespring.com/stores/atun-shei-films

#LeifErikson #Vinland #History

Original Music by Dillon DeRosa ► http://dillonderosa.com/

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/atun_shei~REFERENCES~

[1] Magnus Magnusson & Hermann Pálsson. The Vinland Sagas: The Norse Discovery of America (1965). Penguin Books, Page 59-61

[2] Sîan Grønlie. The Book of the Icelanders / The Story of the Conversion (2006). Viking Society for Northern Research, Page 4

[3] Ingeborg Marshall. “Beothuk Transportation” (1998). Heritage Newfoundland and Labrador https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/a…

[4] Patricia Sutherland. Dorset-Norse Interactions in the Canadian Arctic (2000). Canadian Museum of Civilization, Page 2-9

September 7, 2020

Who Was Leif Erikson?

Atun-Shei Films

Published 9 Oct 2019Happy Leif Erikson Day! Allow me to regale you with the saga of the daring Viking who sailed to North America five hundred years before Columbus (that hack) and called it Vinland. We all know his name and his famous deeds – but what sort of man was Leif Erikson?

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

#LeifErikson #Viking #History

Watch our film ALIEN, BABY! free with Prime ► http://a.co/d/3QjqOWv

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/alienbabymovie

Instagram ► https://www.instagram.com/atunsheifilms

Merch ► https://atun-sheifilms.bandcamp.com

September 5, 2020

History Summarized: The Viking Age

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 4 Sep 2020The Vikings are enjoying a new wave of enthusiasm in popular culture, but these seafaring Norsemen are still quite clearly a misunderstood force in medieval European history. So let’s take a wide look at the European world during The Viking Age!

Check out Yellow’s livestreams over at https://Twitch.tv/LudoHistory

SOURCES & Further Reading: The Vikings by Walaker Nordeide and Edwards, Vikings: A Very Short Introduction by Richards, Age of the Vikings and The Conversion of Scandinavia by Winroth, The Vikings By Harl via The Great Courses, The Viking World by Graham-Campbell, The Viking Way by Price.

This video was edited by Sophia Ricciardi AKA “Indigo”. https://www.sophiakricci.com/

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/kguuvvq

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

From the comments:

Ludohistory

23 hours ago (edited)

Thanks so much for having me on and letting me help out! It was a lot of fun (even if I talked a little too fast sometimes)! To clarify a piece that I know I did cover too briefly — missionary trips to Scandinavia occurred in Denmark around 823, on the orders of Louis the Pious, and in Sweden in 829, when Ansgar, a Frankish monk, traveled to the town of Birka, where he found a very small Christian community, probably mostly enslaved or formerly enslaved people, and converted a couple of Norse people, including the town prefect. (The graveyard for that town, incidentally, is where the 10th century “female warrior” that made waves a few years ago was buried).There’s a lot we didn’t get a chance to talk about about the diaspora and its ending, so if there’s anything you all are curious on or find unclear, let me know here or on twitter 🙂

Finally, if you liked this, all the VODs for my personal streams (where I try to ramble about history in games) can be found by clicking on my name, and tomorrow I’ll be streaming CKIII on twitch (link in the description)!