To tell the story of the fall of a realm, it’s best to start with its rise.

More than three thousand years ago, the Shang dynasty ruled the Chinese heartland. They raised a sprawling capital out of the yellow plains, and cast magnificent ritual vessels from bronze. One of the criteria of civilization is writing, and they had the first Chinese writing, incising questions on turtle shells and ox scapulae, applying a heated rod, and reading the response of the spirits in the pattern of cracks. “This year will Shang receive good harvest?” “Is the sick stomach due to ancestral harm?” “Offer three hundred Qiang prisoners to [the deceased] Father Ding?” The kings of Shang maintained a hegemony over their neighbors through military prowess, and sacrificed war captives from their campaigns totaling in the tens of thousands for the favor of their ancestors.

But the Shang faced growing threat from the Zhou, a once-subordinate people from west beyond the mountains. Inspired by a rare conjunction of the planets in 1059 BC, the Zhou declared that there was such a thing as the Mandate of Heaven, a divine right to rule—and while the Shang had once held it, their misrule and immorality had forced the Mandate to pass to the Zhou. Thirteen years later, the Zhou and their allies defeated the Shang in battle, seized their capital, drove their king to suicide, and supplanted them as overlords of the Central Plains.

If the Shang were goth jocks, the Zhou were prep nerds. In grave goods, food-serving vessels replaced wine vessels. Mass human sacrifice disappeared, while bureaucracy expanded. The Shang lacked the state power to administer their surrounding subject peoples so much as intimidate them into line; the Zhou, galvanized by a rebellion not long after the conquest, put serious thought into consolidating their control. While the king remained in the west to rule over the original Zhou lands, he sent relatives and allies east into the conquered territories to establish colonies at strategically important locations, anchoring Zhou rule in a sprawling network of hereditary regional lords bound together by blood, marriage, custom, and ancestor worship of the Heaven-blessed founding Zhou kings.

For generations, the system worked, ensuring military successes at the borders and stability in the interior. The first reigns of the dynasty became a golden age in the cultural imagination for thousands of years. But by the dynasty’s second century, barbarian incursions were putting the state on the defensive, and surviving records hint at waning control over the regional lords and power struggles at court. 771 BC marked a breaking point, when barbarians allied with disgruntled nobles to overrun the royal domain and kill King You of Zhou.

Legend has it that the king was bewitched by his new consort, a melancholy beauty born from a virgin impregnated by the touch of a black salamander. Desperate to make her laugh, the king pranked his lords by lighting the beacon fires intended to summon them in case of invasion. When she delighted at the sight, he kept playing the same trick until the lords got sick of him and stopped coming, which doomed him when the barbarians actually invaded.

But the historical reality seems to be the usual sordid political struggle around a new consort — and heir — threatening the power of the old one. The original queen’s powerful father allied with barbarians to root out the upstart, only to get maybe more than he bargained for. Sure, he put his grandkid on the throne in the end, but the royal house had been devastated. It would never regain the ancestral lands it had lost to the barbarians, the direct holdings that filled its treasury and provided for its armies. The king retreated east into the Central Plains, playing ground of lords that were now more powerful than him. While the royal line remained symbolically important, as holder of the Mandate of Heaven from which all the states derived their legitimacy, the loss of central authority in every other sense would unleash centuries of intensifying interstate warfare and upheaval.

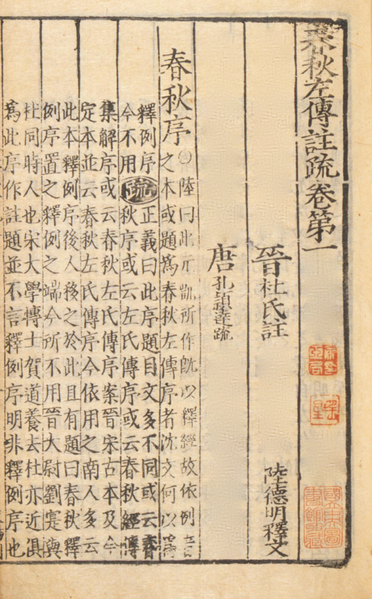

This is the world of the Spring and Autumn Annals, and the Zuozhuan.

The Spring

“Spring and Autumn Annals” is a bit of a redundant translation, since “spring and autumn” was just an old way of saying “year”, and thus, “annals”. And technically, there were multiple Spring and Autumn Annals — every state kept, in addition to court and administrative documents, its own laconic record of each year’s wars, diplomacy, natural phenomena, major rites, and notable deaths. But the state of Lu’s is special, because Confucius was from Lu. He’s said to have personally edited and compiled the extant version of its 242-year-long Spring and Autumn, loading each character with weighty yet subtle moral deliberation. This ensured it a place in the Confucian canon, and its survival where every other state’s annals have been lost to time. The era that it covers is named the Spring and Autumn period after the text, not the other way around.

Taken on its own, though, the Annals is little more than a list of dry facts. For example, the first year reads:

The first year, spring, the royal first month.

In the third month, our lord and Zhu Yifu swore a covenant at Mie.

In summer, in the fifth month, the Liege of Zheng overcame Duan at Yan.

In autumn, in the seventh month, the Heaven-appointed king sent his steward Xuan to us to present the funeral equipment for Lord Hui and Zhong Zi.

In the ninth month, we swore a covenant with a Song leader at Su.

In winter, in the twelfth month, the Zhai Liege came.

Gongzi Yishi died.

Who is Zhu Yifu? Who’s Duan? What’s all this about “overcoming”? Where does the moral deliberation come in? This canon badly needs meta, and the most notable of the ancient commentaries written for the Spring and Autumn Annals is the Zuozhuan. Ten times as long as the text it’s for, the Zuozhuan is the flesh on the Annals‘ bare bones, one of the foundational works of ancient Chinese literature and history-writing in its own right.

While tradition attributes the text’s authorship to Zuo Qiuming, a contemporary of Confucius, most modern historians date its compilation to the century after. In its extant form, it’s presented interleaved with the Annals, so that after the Annals’ account of each year, with entries such as …

In summer, in the sixth month, on the yiyou day (26), Gongzi Guisheng of Zheng assassinated his ruler, Yi.

… you have the Zuozhuan’s account of the year, mostly composed of elaborations upon the above entries, such as:

The leaders of Chu presented a large turtle to Lord Ling of Zheng. Gongzi Song and Gongzi Guisheng were about to have an audience with the lord. Gongzi Song’s index finger moved involuntarily. He showed it to Gongzi Guisheng and said, “On other days when my finger did this, I always without fail got to taste something extraordinary.” As they entered, the cook was about to take the turtle apart. They looked at each other and smiled. The lord asked why, and Gongzi Guisheng told him. When the lord had the high officers partake of the turtle, he called Gongzi Song forward but did not give him any. Furious, Gongzi Song dipped his finger into the cauldron, tasted the turtle, and left. The lord was so enraged that he wanted to kill Gongzi Song. Gongzi Song plotted with Gongzi Guisheng to act first. Gongzi Guisheng said, “Even with an aging domestic animal, one is reluctant to kill it. How much more so then with the ruler?” Gongzi Song turned things around and slandered Gongzi Guisheng. Gongzi Guisheng became fearful and complied with him. In the summer, they assassinated Lord Ling.

The text says, “Gongzi Guisheng of Zheng assassinated his ruler, Yi”: this is because he fell short in weighing the odds. The noble man said, “To be benevolent without martial valor is to achieve nothing.” In all cases when a ruler is assassinated, naming the ruler [with his personal name rather than his title] means that he violated the way of rulership; naming the subject means that the blame lies with him.

There’s a few too many mythological creatures and just-so stories for the Zuozhuan to be taken entirely at face value, but it’s clear that its creator(s) had access to diverse now-lost records for the era portrayed. For example, some of the events show a two-month dating discrepancy — one of the states used a different calendar, and most likely the creator(s) overlooked the difference when borrowing from sources from that state. While the overall level of historical rigor versus 4th century BC authorial invention remains under heated debate, the Zuozhuan is undeniably the most comprehensive written source on its era that we have.

And importantly, it’s enjoyable.

You can think of the Zuozhuan as the Gene Wolfe of ancient historical works. It’s not an easy read, especially in translation, where names that are visibly distinct in the original (e.g. 季, 急, 姬, etc.) all get unhelpfully collapsed into one transliteration (Ji). The work drops you into a whirl of nouns and events, some of them one-off asides, others part of long-running narrative threads that might only surface again decades of entries later. While a casual readthrough still offers plenty of rewards, putting together all the subtext, references, and connections between entries is an endeavor that’s occupied readers for millennia. Your unreliable narrator remains enigmatic on most of the events he presents, leaving interpretation as an exercise for the reader; when he does speak, either directly or in the voice of the “noble man”, he can raise more questions than he answers. For one, the rule about the naming of an assassinated ruler largely holds in the Annals, but seems to have some notable exceptions.

But if you’re willing to plunge in, the work offers an experience unlike anything else.