World War Two

Published 5 Apr 2024What happened to Italian soldiers overseas after the fall of Mussolini? What about the French soldiers left over in Indochina after the Japanese “occupation by invitation”? And, what did the Allies think of the Italian Communist movement and its partisan forces?

(more…)

April 6, 2024

Italian Communists, the French in Indochina, and the fate of Italy’s army – WW2 – OOTF 34

March 7, 2024

QotD: Helmuth von Moltke’s Kabinettskriege of 1870

[The Franco-Prussian War] is generally considered the magnum opus of the titanic Prussian commander, Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke. Exercising deft operational control and an uncanny sense of intuition, Moltke orchestrated an aggressive opening campaign which sent Prusso-German armies streaming like a mass of tentacles into France, trapping the primary French field army in the fortress of Metz in the opening weeks of the war and besieging it. When the French Emperor, Napoleon III, marched out with a relief army (comprising the rest of France’s battle-worthy formations), Moltke hunted that army down as well, encircling it at Sedan and taking the entire force (and the emperor) into captivity.

From an operational perspective, this sequence of events was (and is) considered a masterclass, and a major reason why Moltke has become revered as one of history’s truly great talents (he is on this writer’s Mount Rushmore alongside Hannibal, Napoleon, and Manstein). The Prussians had executed their platonic ideal of warfare — the encirclement of the main enemy body — not once, but twice in a matter of weeks. In the conventional narrative, these great encirclements became the archetype of the German kesselschlacht, or encirclement battle, which became the ultimate goal of all operations. In a certain sense, the German military establishment spent the next half-century dreaming of ways to replicate its victory at Sedan.

This story is true, to a certain extent. My objective here is not to “bust myths” about blitzkrieg or any such trite thing. However, not everyone in the German military establishment looked at the Franco-Prussian War as an ideal. Many were terrified by what happened after Sedan.

By all rights, Moltke’s masterpiece at Sedan should have ended the war. The French had lost both of their trained field armies and their head of state, and ought to have given in to Prussia’s demand (namely, the annexation of the Alsace-Lorraine region).

Instead, Napoleon III’s government was overthrown and a National Government was declared in Paris, which promptly declared what amounted to a total war. The new government abandoned Paris, declared a Levee en Masse — a callback to the wars of the French Revolution in which all men aged 21 to 40 were to be called to arms. Regional governments ordered the destruction of bridges, roads, railways, and telegraphs to deny their use to the Prussians.

Instead of bringing France to its knees, the Prussians found a rapidly mobilizing nation which was determined to fight to the death. The mobilization prowess of the emergency French government was astonishing: by February, 1871, they had raised and armed more than 900,000 men.

Fortunately for the Prussians, this never became a genuine military emergency. The newly raised French units suffered from poor equipment and poor training (particularly because most of France’s trained officers had been captured in the opening campaign). The new mass French armies had poor combat effectiveness, and Moltke managed to coordinate the capture of Paris alongside a campaign which saw Prussian forces marching all over France to run down and destroy the elements of the new French Army.

Big Serge, “The End of Cabinet War”, Big Serge Thought, 2023-11-30.

February 22, 2024

The Malayan Emergency – Britain’s Jungle War v Communists

The History Chap

Published Nov 16, 2023Britain’s Victorious Jungle War Against the Communists

Get My FREE Weekly Newsletter

https://www.thehistorychap.com

January 31, 2024

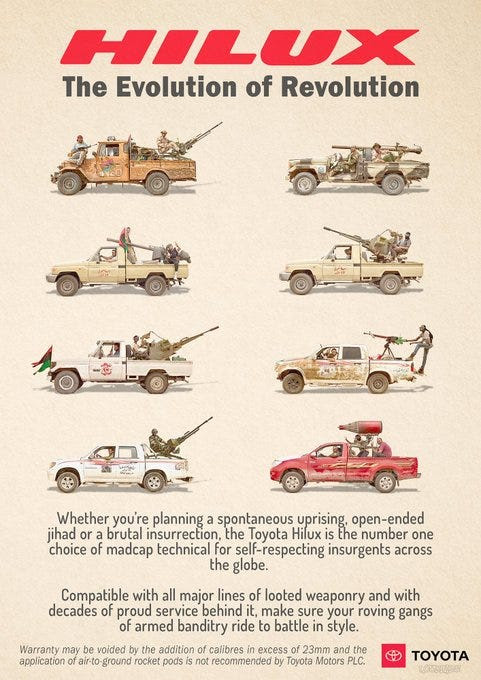

The rise of the “Technical”

Kulak at Anarchonomicon considers the innovation and adaptability that Chad’s ragtag forces displayed in the late 1980s to drive Libyan forces out of their territory, specifically the military use of Toyota pickup trucks as improvised gun carriages:

The Great Toyota War of 1987 was the final phase of the Chadian-Libyan conflict. Gadhafi’s Libyan forces by all rights should have dominated the vast stretches of desert being fought over: the Chadian military was less than a 3rd the size of the Libyan, and the Libyans were vastly better equipped fielding hundreds of tanks and armored personnel carriers, in addition to dozens of aircraft … to counter this the Chadians did something unique … They mounted the odds and ends heavy weapons systems they had in the truck beds of their Toyota pickups, and using the speed and maneuverability of the Toyotas, managed to outperform Libya’s surplus tanks and armored vehicles. By the end of the Chadian assault to retake their northern territory, the Libyans had suffered 7500 casualties to the Chadians 1000, with the Libyan defeat compounded by the loss of 800 armored vehicles, and close to 30 aircraft captured or destroyed.

The maneuverability and speed of the pickups made them incredibly hard to hit, and the tanks in particular struggled to get a sight picture … strafing within a certain range the pickups moved faster across the horizon than the old soviet tanks’ main gun could be hand cranked around to shoot them.

Since then Technology has become the backbone of insurgencies, militias, poorer militaries, and criminal cartels around the world. The ready availability of civilian pickups, with the ability of amateur mechanics to mount almost any weapon system in their truck-bed means that this incredibly simple system is about the most cost-effective and easy way for a small force to make the jump to mounted combat and heavy weapon.

But these weapons are far less asymmetric than motorcycles. The increasing importance of mobility means even the most advanced armies are getting in on the game. The US Army is currently converting a portion of its Humvees to have their rear seat and trunk cut out for a truck bed so that they can run a mobile light artillery out of it:

Popular Mechanics article – https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/weapons/a28288/hawkeye-humvee-mounted-howitzer/

The importance of instant maneuverability far outstretches any advantage armor can give in this application. Since artillery shells are radar-detectable, and, follow a parabolic arc, their origin point is easily calculable. Thus shoot and Scoot tactics are necessary since it may only be a minute or two from firing a volley that counter artillery fire might be inbound.

Aside from The bemused jokes that the US is finally catching up with the tech Chad had in the 80s, The truth is most advanced forces have always had something light with a heavy gun that can travel at highway speeds … the fact the US is now converting Humvees to have full light artillery pieces is only really a continuation of the trend of semi-auto grenade launchers, TOW missiles, or anti-tank guns being placed on light fast vehicles since WW2.

The remarkable thing about the technical isn’t that they’re some unique capability militaries can’t use … most poorer countries field something equivalent (the Libyans seemed to have screwed up the unit composition of their force) … Rather the unique advantage is how easy and cheap they are for non-conventional or poorer forces to home assemble.

US combat-ready Humvees cost the military into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, a cost that is presumably even higher as they’re modified to carry heavy weapons systems.

As ridiculous as a Toyota with an Air-to-Ground rocket pod, or a repurposed anti-air gun might be, they’re cheap. The pickup truck new is $20,000-50,000, though I suspect any irregular force would pay closer to 1000-5,000 for something decades old, if they pay at all. Likewise, they’re trivial to source, which is good if sanctions or anti-money laundering laws are trying to stop you from buying anything, and as the Chadians proved: pretty much any captured or surplus heavy weapon will go on it.

This gets irregular forces into the mounted combat game … but it does slightly more than that. Pickup trucks, as any perturbed Prius driver will tell you, are shockingly common … perhaps one in 10 or more vehicles out there are some form of pickup truck. This not only makes them easy to source, but it disguises them and allows them to operate hidden amongst the rolling stock of civilian vehicles, requiring either visual identification or extensive intelligence work to tell them from mere civilians.

This combination of mobility, resemblance to civilian vehicles, and ability to deploy heavy weapons was used to devastating effect by the Islamic State during the 2014 Fall of Mosul. Striking quickly while Iraqi national tanks were deployed elsewhere the small Islamic force entered the city at 2:30 am, striking in small convoys that overwhelmed checkpoints with their firepower, executing and torturing captured Iraqi soldiers and targeted enemies as they went. Even after taking into account desertions and “ghost soldiers” (fake soldiers meant to pad unit numbers so corrupt officials could collect their pay) which significantly reduced the 30,000 Iraqi army and 30,000 police within the city … Even after allowing for all that, the Iraqi national forces still outnumbered the 800-1500 ISIS fighters at a rate of 15 to 1.

YET ISIS was able to achieve a total victory and take the whole of the city within 6 days.

2 years later it would take the Iraqi government with American backing 9 months to retake it.

How? How does a force of 1500 at most, most without any formal training, overwhelm and defeat a force of 12,000-23,000, which at least has some training, better equipment, and has an entire state behind it? How did ISIS do this entirely without air support? Even as the Iraqi government bombed them from helicopters?

How did they take in 6 days what would take the Iraqi government with full American backing 9 months to retake?

Well, they made the Iraqis break and run.

January 22, 2024

QotD: Mao’s theory of “protracted war” as adapted to Vietnamese conditions by Võ Nguyên Giáp

The primary architect of Vietnam’s strategy, initially against French colonial forces and then later against the United States and the US-backed South Vietnamese (Republic of Vietnam or RVN) government was Võ Nguyên Giáp.

Giáp was facing a different set of challenges in Vietnam facing either France or the United States which required the framework of protracted war to be modified. First, it must have been immediately apparent that it would never be possible for a Vietnamese-based army to match the conventional military capability of its enemies, pound-for-pound. Mao could imagine that at some point the Red Army would be able to win an all-out, head-on-head fight with the Nationalists, but the gap between French and American capabilities and Vietnamese Communist capabilities was so much wider.

At the same time, trading space for time wasn’t going to be much of an option either. China, of course, is a very large country, with many regions that are both vast, difficult to move in, and sparsely populated. It was thus possible for Mao to have his bases in places where Nationalist armies literally could not reach. That was never going to be possible in Vietnam, a country in which almost the entire landmass is within 200 miles of the coast (most of it is far, far less than that) and which is about 4% the size of China.

So the theory is going to have to be adjusted, but the basic groundwork – protract the war, focus on will rather than firepower, grind your enemy down slowly and proceed in phases – remains.

I’m going to need to simplify here, but Giáp makes several key alterations to Mao’s model of protracted war. First, even more than Mao, the political element in the struggle was emphasized as part of the strategy, raised to equality as a concern with the military side and fused with the military operation; together they were termed dau tranh, roughly “the struggle”. Those political activities were divided into three main components. Action among one’s own people consisted of propaganda and motivation designed to reinforce the will of the populace that supported the effort and to gain recruits. Then, action among the enemy people – here meaning Vietnamese who were under the control of the French colonial government or South Vietnam and not yet recruited into the struggle – a mix of propaganda and violent action to gain converts and create dissension. Finally, action against the enemy military, which consisted of what we might define as terroristic violence used as message-sending to negatively impact enemy morale and to encourage Vietnamese who supported the opposition to stop doing so for their own safety.

Part of the reason the political element of this strategy was so important was that Giáp knew that casualty ratios, especially among guerrilla forces – on which, as we’ll see, Giáp would have to rely more heavily – would be very unfavorable. Thus effective recruitment and strong support among the populace was essential not merely to conceal guerrilla forces but also to replace the expected severe losses that came with fighting at such a dramatic disadvantage in industrial firepower.

That concern in turn shaped force-structure. Giáp theorized an essentially three-tier system of force structure. At the bottom were the “popular troops”, essentially politically agitated peasants. Lightly armed, minimally trained but with a lot of local knowledge about enemy dispositions, who exactly supports the enemy and the local terrain, these troops could both accomplish a lot of the political objectives and provide information as well as functioning as local guerrillas in their own villages. Casualties among popular troops were expected to be high as they were likely to “absorb” reprisals from the enemy for guerrilla actions. Experienced veterans of these popular troops could then be recruited up into the “regional troops”, trained men who could now be deployed away from their home villages as full-time guerrillas, and in larger groups. While popular troops were expected to take heavy casualties, regional troops were carefully husbanded for important operations or used to organize new units of popular troops. Collectively these two groups are what are often known in the United States as the Viet Cong, though historians tend to prefer their own name for themselves, the National Liberation Front (Mặt trận Dân tộc Giải phóng miền Nam Việt Nam, “National Liberation Front for South Vietnam”) or NLF. Finally, once the French were forced to leave and Giáp had a territorial base he could operate from in North Vietnam, there were conventional forces, the regular army – the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) – which would build up and wait for that third-phase transition to conventional warfare.

The greater focus on the structure of courses operating in enemy territory reflected Giáp’s adjustment of how the first phase of the protracted war would be fought. Since he had no mountain bases to fall back to, the first phase relied much more on political operations in territory controlled by the enemy and guerrilla operations, once again using the local supportive population as the cover to allow guerrillas and political agitators (generally the same folks, cadres drawn from the regional troops to organize more popular troops) to move undetected. Guerrilla operations would compel the less-casualty-tolerant enemy to concentrate their forces out of a desire for force preservation, creating the second phase strategic stalemate and also clearing territory in which larger mobile forces could be brought together to engage in mobile warfare, eventually culminating in a shift in the third phase to conventional warfare using the regional and regular troops.

Finally, unlike Mao, who could envision (and achieve) a situation where he pushed the Nationalists out of the territories they used to recruit and supply their armies, the Vietnamese Communists had no hope (or desire) to directly attack France or the United States. Indeed, doing so would have been wildly counter-productive as it likely would have fortified French or American will to continue the conflict.

That limitation would, however, demand substantial flexibility in how the Vietnamese Communists moved through the three phases of protracted war. This was not something realized ahead of time, but something learned through painful lessons. Leadership in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV = North Vietnam) was a lot more split than among Mao’s post-Long-March Chinese Communist Party; another important figure, Lê Duẩn, who became general secretary in 1960, advocated for a strategy of “general offensive” paired with a “general uprising” – essentially jumping straight to the third phase. The effort to implement that strategy in 1964 nearly overran the South, with ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam – the army of South Vietnam) being defeated by PAVN and NLF forces at the Battles of Bình Giã and Đồng Xoài (Dec. 1964 and June 1965, respectively), but this served to bring the United States more fully into the war – a tactical and operational victory that produced a massive strategic setback.

Lê Duẩn did it again in 1968 with the Tet Offensive, attempting a general uprising which, in an operational sense, mostly served to reveal NLF and PAVN formations, exposing them to US and ARVN firepower and thus to severe casualties, though politically and thus strategically the offensive ended up being a success because it undermined American will to continue the fight. American leaders had told the American public that the DRV and the NLF were largely defeated, broken forces – the sudden show of strength exposed those statements as lies, degrading support at home. Nevertheless, in the immediate term, the Tet Offensive’s failure on the ground nearly destroyed the NLF and forced the DRV to back down the phase-ladder to recover. Lê Duẩn actually did it again in 1972 with the Eastern Offensive when American ground troops were effectively gone, exposing his forces to American airpower and getting smashed up for his troubles.

It is difficult to see Lê Duẩn’s strategic impatience as much more than a series of blunders – but crucially Giáp’s framework allowed for recovery from these sorts of defeats. In each case, the NLF and PAVN forces were compelled to do something Mao’s model hadn’t really envisaged, which was to transition back down the phase system, dropping back to phase II or even phase I in response to failed transitions to phase III. By moving more flexibly between the phases (while retaining a focus on the conditions of eventual strategic victory), the DRV could recover from such blunders. I think Wayne Lee actually puts it quite well that whereas Mao’s plan relied on “many small victories” adding up to a large victory (without the quick decision of a single large victory), Giáp’s more flexible framework could survive many small defeats on the road to an eventual strategic victory when the will of the enemy to continue the conflict was exhausted.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How the Weak Can Win – A Primer on Protracted War”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-03-03.

January 21, 2024

A Book and a Rifle: The Vercors Resistance in WWII

Forgotten Weapons

Published 20 May 2018One of the single largest actions of the French Resistance during World War Two was Operation Montagnards — the plan to drop about 4,000 Allied paratroops onto the Vercors Massif when the resistance was activated in support of the Allied landings in Normandy and Provence. If you are scratching your head trying to figure out why you don’t remember that operation, it is because it never actually happened. The two Allied landings were originally intended to take place simultaneously, but logistical limitations forced the southern landings to be delayed about two months. In an deliberate decision to prevent the Germans from immediately understanding the nature of the Allied attack, the whole of the French Resistance was activated to support the Normandy landings in June 1944. The internal attacks in the south would force the Germans to keep significant forces in that area in expectation of a second landing, which would increase the chances of the Normandy landings succeeding. Unfortunately, the other result of this decision was that Resistance cells would come into the open in anticipation of imminent military support, which would not be coming. The southern elements of the Resistance were basically sacrificed in this gambit.

The Vercors Massif is a large geographical feature near Lyon and Grenoble which comprises basically a triangular sheer-walled plateau rising well above the surrounding plains. It offers a fantastically defensible redoubt, and that is what it was planned to be. Paratroops dropped onto the top of the massif would reinforce a substantial force of Maquis fighters, and create a serious strong point behind the German lines to aid in the fight inland from the landing beaches. The plan was organized in Algiers by Resistance representatives from the Vercors and Free French officers earlier in the war. Some have argued that the lack of support was simply due to the compromises of the single-landing plan, while others fault de Gaulle for deliberately abandoning the men and women on Vercors as part of a strategy to consolidate post-war political support — but that debate is beyond the scope of today’s discussion.

The fighters and civilians on the massif ultimately held out for about 6 weeks — only just too little to still be there when the Allied armored columns reached Grenoble. The German commander in the area spent several weeks making small probing attacks before the final assault with about 10,000 veteran Wehrmacht soldiers, glider-borne infantry, and tanks. Once that attack came, the fate of the Vercors was sealed. With proper military backing they could have defended their redoubt, but instead they had only a smattering of small arms and no heavy weaponry at all. It was a fight that was gloriously courageous but hopelessly doomed to failure.

I am privileged to have in my own collection a Berthier carbine tied to the Vercors Resistance, as evidenced by the brass embellishments on its stock. While I cannot conclusively prove it came from the Resistance, it was sold to me without any premium attached to them, and I have no reason to believe it is fake. And, of course, since I have no plans to sell it, I am not really concerned about conclusively proving its veracity to others. For me, it is a poignant icon of a tremendously heroic group. I hope I would live up to the bar they set should I ever be in a comparable situation!

(more…)

January 8, 2024

QotD: Nomadic cultures’ territorial needs

This bears little resemblance to the strategic concerns of historical nomads. As a direct consequence of failing to understand the subsistence systems that nomads relied on, [George R.R.] Martin [in his descriptions of the Dothraki nomad culture] has also rendered their patterns of warfare functionally unintelligible.

The chief thing that nomads, both Great Plains Native Americans and Eurasian Steppe Nomads used violence to secure control of is the one thing the Dothraki never do: territory. To agrarian elites (who write most of our sources) and modern viewers, the vast expanses of grassland that nomads live on often look “empty” and “unused” (and thus not requiring protection), but that’s not correct at all. Those “empty” grasslands are very much in use; the nomads know this and are abundantly willing to defend those expanses of grass with lethal force to keep out interlopers. Remember: the knife’s edge of subsistence for nomads is very thin indeed, so it takes only a small disruption of the subsistence system to push the community into privation.

For the Eurasian Steppe nomad, the grass that isn’t near their encampment is in the process of regrowth for the season or year when it will be near their encampment and need to support their herds. Allowing some rival nomadic group to move their sheep and their horses over your grassland – eating the essential grass along the way – means that grass won’t be there for your sheep and your horses when you need it; and when the sheep starve, so will you. So if you are stronger than the foreign interloper, you will gather up all of your warriors and confront them directly. If you are weaker, you will gather your warriors and raid the interloper, trying to catch members of their group when they’re alone, to steal horses and sheep (we’ll come back to that); you are trying to inflict a cost for being on your territory so that they will go away and not come back.

The calculus for nomadic hunters like the Great Plains Native Americans is actually fairly similar. Land supports bison, bison support tribal groupings, so tribal groups defend access to land with violent reprisals against groups that stray into their territory or hunt “their” bison. And of course the reverse is true – these groups aren’t merely looking to hold on to their own territory, but to expand their subsistence base by taking new territory. Remember: the large tribe is the safe tribe; becoming the large tribe means having a larger subsistence base. And on either the plains or the steppe, the subsistence base is fundamentally measured in grass and the animals – be they herded sheep or wild bison – that grass supports. Both Secoy and McGinnis (op. cit.) are full of wars of these sorts on the Great Plains, where one group, gaining a momentary advantage, violently pushes others to gain greater territory (and thus food) for itself. For instance, Secoy (op. cit., 6-32) discusses how access to horses allowed the Plains Apache to rapidly violently expand over the southern Plains in the late 17th century, before being swept off of them by the fully nomadic Ute and Comanche in the first third of the 18th. As McGinnis notes (op. cit., 16ff), on the Northern Plains, prior to 1800 it initially was the Shoshone who were dominant and expanding, but around 1800 began to be pushed out by the Blackfoot, who in turn would, decades later, be pushed by the expanding Sioux.

This kind of warfare is different from the way that settled, agrarian armies take territory. Generally, the armies of agrarian states seek to seize (farm-) land with its population of farmers mostly intact and exert control both over the land and the people subsequently in order to extract the agricultural surplus. But generally (obviously there are notable exceptions) nomads both lack the administrative structures to exert that kind of control and are also very able to effectively resist that sort of control themselves (it is hard for even nomads to tax nomads), making “empire building” along agrarian lines difficult or undesirable (unless you are the Mongols). So instead, polities are trying to inflict losses (typically more through raiding and ambush than battle). Since rivals will tend to avoid areas that become unsafe due to frequent raiding, the successful tribe can essentially push back an opposing tribe with frequent raids. In extreme circumstances, a group may feel threatened enough to get up and move entirely – which of course creates conflict wherever they go, since their plan is to disposess the next group along the way of their territory.

Within that security context, larger scale groupings – alliances, confederations, and super-tribal “nations” – are common. On the Eurasian Steppe, such alliances tended to be personal, although there was a broad expectation that a given ethnic grouping would work together against other ethnic groupings (an expectation that Chinggis actually worked very hard, once he became the Great Khan of a multi-ethnic “Mongol” army, to break up through the decimal organization system; this reorganization is part of what made the Mongol Empire so much more successful than previous Steppe confederations). Likewise, even a cursory look at the Native Americans of the Great Plains produces both a set of standard enmities (the Sioux and the Crow, for instance) but also webs of peace agreements, treaties, alliances, confederations and so on. The presence of British, French, Spanish and American forces (both traders and military forces) fit naturally into that system; the Plains Apache allied with the Spanish against the Comanche, the Crow with the United States against the Sioux and so on. Such allies might not only help out in a conflict, but also deter war and raiding because their strength and friendship made lethal retaliation likely (don’t attack someone allied to Chinggis Khan and expect to survive the experience …).

Exactly none of that complexity appears with the Dothraki, who have no alliances, no peace agreements, no confederations and no territory to attack or defend. Instead, the Dothraki simply sail around the grass sea, fighting whenever they should chance to meet.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: That Dothraki Horde, Part IV: Screamers and Howlers”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-01-08.

December 13, 2023

How Churchill Started the Cold War in Greece in 1944 – War Against Humanity 121

World War Two

Published 12 Dec 2023You might think that the Cold War starts after this war ends. But already, as the Germans withdraw from Greece, the ideologically opposed Greek resistance groups ELAS and EDES are at each others’ throats. It all culminates in Athens in December 1944; British troops fire some of the first shots of the Cold War as Greece descends into Civil War.

(more…)

November 9, 2023

Defending a stateless society: the Estonian way

David Friedman responded to a criticism of his views from Brad DeLong. Unfortunately, the criticism was written about a decade before David saw it, so he posted his response on his own Substack instead:

English version of the Estonian Defence League’s home page as of 2023-11-08.

https://www.kaitseliit.ee/en

Back in 2013 I came across a piece by Brad DeLong critical of my views. It argued that there were good reasons why anarcho-capitalist ideas did not appear until the nineteenth century, reasons illustrated by how badly a stateless society had worked in the Highlands of Scotland in the 17th century. I wrote a response and posted it to his blog, then waited for it to appear.

I eventually discovered what I should have realized earlier — that his post had been made nine years earlier. It is not surprising that my comment did not appear. The issues are no less interesting now than they were then, so here is my response:

Your argument rejecting a stateless order on the evidence of the Scottish Highlands is no more convincing than would be a similar argument claiming that Nazi Germany or Pol Pot’s Cambodia shows how bad a society where law is enforced by the state must be. The existence of societies without state law enforcement that work badly — I do not know enough about the Scottish Highlands to judge how accurate your account is — is no more evidence against anarchy than the existence of societies with state law enforcement that work badly is against the alternative to anarchy.

To make your case, you have to show that societies without state law enforcement have consistently worked worse than otherwise similar societies with it. For a little evidence against that claim I offer the contrast between Iceland and Norway in the tenth and eleventh centuries or northern Somalia pre-1960 when, despite some intervention by the British, it was in essence a stateless society, and the situation in the same areas after the British and Italians set up the nation of Somalia, imposing a nation state on a stateless society. You can find short accounts of both those cases, as well as references and a more general discussion of historical feud societies, in my Legal Systems Very Different From Ours. A late draft is webbed.

So far as the claim that the idea of societies where law enforcement is private is a recent invention, that is almost the opposite of the truth. The nation state as we know it today is a relatively recent development. For historical evidence, I recommend Seeing Like a State by James Scott, who offers a perceptive account of the ways in which societies had to be changed in order that states could rule them.

As best I can tell, most existing legal systems developed out of systems where law enforcement was private — whether, as you would presumably argue, improving on those systems or not is hard to tell. That is clearly true of, at least, Anglo-American common law, Jewish law and Islamic law, and I think Roman law as well. For details again see my book.

In which context, I am curious as to whether you regard yourself as a believer in the Whig theory of history, which views it as a story of continual progress, implying that “institutions A were replaced by institutions B” can be taken as clear evidence of the superiority of the latter.

And From the Real World

In chapter 56 of the third edition of The Machinery of Freedom I discussed how a stateless society might defend against an aggressive state, which I regard as the hardest problem for such a society. One of the possibilities I raise is having people voluntarily train and equip themselves for warfare for the fun (and patriotism) of it, as people now engage in paintball, medieval combat in the Society for Creative Anachronism, and various other military hobbies.

A correspondent sent me a real world example of that approach — the Estonian Defense League, civilian volunteers trained in the skills of insurgency. They refer to it as “military sport”. Competitions almost every week.

Estonia’s army of 6000 would not have much chance against a Russian invasion but the Estonians believe, with the examples of Iraq and Afghanistan in mind, that a large number of trained and armed insurgents could make an invasion expensive. The underlying principle, reflected in a Poul Anderson science fiction story1 and one of my small collection of economics jokes,2 is that to stop someone from doing something you do not have to make it impossible, just unprofitable. You can leverage his rationality.

Estonia has a population of 1.3 million. The league has 16,000 volunteers. Scale the number up to the population of the U.S. and you get a militia of about four million, roughly twice the manpower of the U.S. armed forces, active and reserve combined. The League is considered within the area of government of the Ministry of Defense, which presumably provides its weaponry; in an anarchist equivalent the volunteers would have to provide their own or get them by voluntary donation. But the largest cost, the labor, would be free.

Switzerland has a much larger military, staffed by universal compulsory service, but there are also private military associations that conduct voluntary training in between required military drills. Members pay a small fee that helps fund the association and use their issued arms and equipment for the drills.

1. The story is “Margin of Profit“. I discuss it in an essay for a work in progress, a book or web page containing works of short literature with interesting economics in them.

2. Two men encountered a hungry bear. One turned to run. “It’s hopeless,” the other told him, “you can’t outrun a bear.” “No,” he replied, “But I might be able to outrun you.”

October 14, 2023

Why Did the Vietnam War Break Out?

Real Time History

Published 10 Oct 2023In 1965, US troops officially landed in Vietnam, but American involvement in the ongoing conflict between the Communist North and the anti-Communist South had started more than a decade earlier. So, why did the US-Vietnam War break out in the first place?

(more…)

October 2, 2023

Why France Lost Vietnam: The Battle of Dien Bien Phu

Real Time History

Published 29 Sept 2023After the French success in the Battle of Na San, the battle of Dien Bien Phu is supposed to defeat the Viet Minh once and for all. But instead the weeks-long siege becomes a symbol of the French defeat in Vietnam.

(more…)

September 22, 2023

Is the Slovak Uprising Doomed to Fail? – War Against Humanity 115

World War Two

Published 21 Sep 2023Even as they battle an uprising in Slovakia, the Nazis see the opportunity to continue their racial realignment of Europe. The latest victims of this genocidal legacy are Anne Frank and her family, who arrive at Auschwitz. In Britain, the V-1 menace is defeated. But as London breathes a sigh of relief, the Nazis and their allies reduce Warsaw to rubble in a rampage of burning, looting, rape, and murder.

(more…)

September 16, 2023

France’s Vietnam War: Fighting Ho Chi Minh before the US

Real Time History

Published 15 Sept 2023After the Second World War multiple French colonies were pushing towards independence, among them Indochina. The Viet Minh movement under Ho Chi Minh was clashing with French aspirations to save their crumbling Empire.

(more…)

September 7, 2023

How Britain Helped the Communist Revolution – War Against Humanity 113

World War Two

Published 6 Sep 2023Fight the Nazis or fight your countrymen? From Marshal Tito’s Partisans in Yugoslavia to the ELAS fighters in Greece, that is the animating question among the Balkans resistance movements. For many, the question is already answered. It is Mihailović and his Chetniks and EDES, EKKA, and the Greek royalist government who must be out-maneuvered first. British foreign policy has so far failed to change this state of affairs, can Churchill get his SOE officers to stop these civil wars?

(more…)

September 1, 2023

Will the Resistance Smash Nazism or Build Communism? – War Against Humanity 112

World War Two

Published 31 Aug 2023The hour of resistance is here. Across Western Europe, armies of resistance fighters rise up to meet the Allied armies and sabotage the Axis war machine. In Slovakia, a secret army fights to restore Czechoslovak independence. But against this hopeful backdrop, the Axis forces strike back hard. And, all around, the spectre of communism strikes fear in the Western Powers.

(more…)