Forgotten Weapons

Published on 25 Jun 2019http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

Over many years of filming with my high speed camera, I have a decent little library of malfunctions in a wide variety of guns. These don’t normally make it into videos, and I figured it would be neat to present a bunch of them together. Enjoy!

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

PO Box 87647

Tucson, AZ 85754

August 21, 2019

Slow Motion Malfunctions of Exotic Firearms

August 18, 2019

AAI 2nd Gen SPIW Flechette Rifles

Forgotten Weapons

Published on 24 Jun 2019http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

The SPIW program began in 1962 with entries from Colt, Springfield, AAI, and Winchester. The first set of trials were a complete failure, and both Colt and Winchester abandoned the project at that point. AAI pressed on, producing these second generation rifles – one for trials in 1966 and one after. Both are chambered for the XM-645 5.6x57mm single-flechette cartridge. Under testing, both showed multiple serious problems in reliability, noise, cook-offs, and accuracy. The company would struggle on for years continuing to develop the flechette rifle system, but would be ultimately unsuccessful.

Thanks to the Rock Island Arsenal Museum for allowing me access to film this very interesting rifle! If you are in the Quad Cities in Illinois or Iowa, the Museum is definitely worth a visit. They have a great number of small arms on display as well as an excellent history of the Rock Island Arsenal.

http://www.arsenalhistoricalsociety.o…

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

PO Box 87647

Tucson, AZ 85754

August 3, 2019

We finally get an explanation for Justin Trudeau’s diplomatically catastrophic India tour

A few days ago, I noted on social media:

This is exactly the sort of suave, diplomatic polish that will smooth over all the damage in the Canada-India relationship. This is a quote from PM Trudeau’s right-hand man in John Ivison’s new book:

“We walked into a buzzsaw — (Narendra) Modi and his government were out to screw us and were throwing tacks under our tires to help Canadian conservatives, who did a good job of embarrassing us,”

http://thepostmillennial.com/out-to-screw-us-butts-blames-indian-pm-for-trudeaus-disastrous-trip/ #JustinTrudeau #India #fiasco #books #GeraldButts #NarendraModi #diplomacy

I figured this had to be some kind of new variant of the old “modifed limited hangout“, but it’s so potentially damaging to an already badly frayed relationship that there had to be more to it … possibly a lot more to it. No rational senior official would say something like that unless there was a much worse revelation that it was intended to camouflage. But whatever it was would have to be “recall the High Commissioner” bad to justify that kind of self-inflicted diplomatic wound.

Brian Lilley is similarly puzzled, but he has a simpler explanation: it’s that familiar combination of the Trudeau unwillingness to take responsibility, an over-developed blame-casting habit, and Trudeau’s own frequently demonstrated love of wearing costumes:

It’s one thing for Butts to think those things, another to voice them in a way that he knows will be made public. It’s also the most tone-deaf assessment of the trip I’ve seen since Sophie Trudeau went on TV and blamed the staff for those outfits.

I mean think about that trip, the two things that got Trudeau in trouble were the invite of the terrorist to dinner and the outrageous outfits. Both of those amount to self-inflicted wounds.

At least Butts admits the photos of Trudeau and his family were a problem.

“Nobody would remember any of that had it not been for the photographs. We should have known this better than anybody — in many ways we’d used this to get elected. The picture will overwhelm words. We did the count — we did forty-eight meetings and he was dressed in a suit for forty-five of them. But give people that picture and it’s the only one they’ll remember,” Butts told Ivison.

[…]

The simple fact of the matter is that the trip to India was a disaster, the kind Trudeau and his team weren’t used to dealing with. So now a year and half later they are still looking to lay the blame anywhere but where it belongs.

With themselves.

July 11, 2019

To lose one VCDS may be regarded as misfortune; to lose five looks like horrific leadership failure

(Apologies to Oscar for my misappropriation of his phrasing for the title of this post.) The current Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff has announced his resignation. Lieutenant General Paul Wynnyk will resign from his current role after rumours circulated that he was to be replaced with former VCDS Vice-Admiral Mark Norman. Ted Campbell has more:

I see, from a story on Global News, broken by Mercedes Stephenson, of Global and David Pugliese (Post Media), two journalists with very good sources inside DND and the Canadian Armed Forces, that “The second in command of Canada’s military Lt.-Gen. Paul Wynnyk is resigning after he said Chief of the Defence Staff General Jonathan Vance planned to replace him as the vice chief of the defence staff with Vice-Admiral Mark Norman … [but] … Vance then reversed that plan weeks later, according to Wynnyk, when Norman settled with the government and retired from the military.”

Lieutenant General “Wynnyk was the fifth vice chief to serve under Vance, and questions are now being raised about his leadership, senior military sources told Global News … [and, the report says] … There are now questions about who will fill the job next. No one appears to be ready, the sources said.” With the utmost respect to Mercedes Stephenson’s sources, who are, I suspect three and two-star admirals and generals, almost any general officer is “ready” to be Vice Chief of the Defence Staff or to fill almost any other “flag” appointment (jobs like surgeon general and the judge advocate general being obvious exceptions). I lived through times when the head of the Army’s equipment engineering branch was not an engineer ~ but was picked specifically because he could lead and manage people and could leave the “engineering” to subordinates, and when a logistics officer ran the Army, to the horror or a few combat branch dinosaurs, and when a Signals officer was Chief of the Defence Staff, too, because, at the time, the top leaders still understood that generals are generalists. I will assert, some will disagree but they are wrong, that almost every rear admiral and major general, from almost every corner of the military, is “ready” right now, to be Chief of the Defence Staff and almost every commodore and brigadier general is equally “ready” to be the Vice Chief. If that is not the case then the Canadian Forces’ leadership system is in a crisis right now, which only a wholesale slaughter of admirals and generals will rectify … or else there will be a slaughter of young Canadian men and women when our armed forces muct face a near-peer enemy.

At the risk of repeating myself:

- The current military command and control (C²) superstructure is beyond bloated, it is morbidly obese;

- The military C² system has things back-asswards ~ staff officers outrank combat commanders. We have commodores and brigadier generals sitting behind big desks in Ottawa when they ought to be commanding flotillas, brigades and air groups. The desks in HQs should be occupied by Navy captains and commanders and Army and RCAF colonels and lieutenant colonels, all of whom are, already, proven executives;

- The CDS should be a three-star officer, a vice admiral or a lieutenant general ~ Canada, with only about 110,000 men and women, regular and reserve, in uniform, doesn’t need a four-star CDS. Reducing her or his rank would be an act “pour encourager les autres;”

- The military’s command culture must start with getting the foundation right. The recruiting, selection, training and development of junior leaders, corporals and 2nd lieutenants (using the Army as my example), must be the highest priority for every single senior officer. If the foundation is solid then developing admirals and generals will not be a problem. If, as I suspect, the foundation is weak, if there is rank inflation, as I assert there is, at the tank/rifle section and troop/platoon command levels, then problems are going to persist and be magnified at the unit (ship, regiment or squadron), formation (group, brigade, wing and higher) and command levels and in National Defence HQ, too. Eventually, if the foundation is weak then we, Canadians will pay the price in blood … the blood of our sons and daughters and grandsons and granddaughters.

June 6, 2019

iTunes is dead – “There will be no funeral, because it had no friends”

I use iTunes because I have to, not because I particularly want to. Apparently that’s not uncommon among iPhone users:

iTunes, Apple’s Frankenstein’s monster of an MP3-player-cum-record store-cum-video-store-cum-iPhone-updater-cum-random-task-performer, a piece of software which opens on your computer whenever it wants and which seems to require you to download an updated version every eight hours, was pronounced dead on Monday. It was 19 years old. There will be no funeral, because it had no friends.

Apple CEO Tim Cook announced that in its future operating systems, iTunes will be replaced by three separate programs: One for music (Apple Music), one for podcasts (Apple Podcasts) and one for video (Apple TV). Updating your phone — which never had anything to do with music, podcasts or video — will now be a function of the operating system. This sounds promising. It sounds normal.

But the mystery remains how Apple, of all companies, found itself sullying its machines for so long with iTunes’ wretched presence. By the end iTunes wasn’t just bad, it was fascinatingly bad — a “toxic hellstew,” as programmer Marco Arment put it in 2015. It was a master class in bad user experience from a company whose brand is excellent user experience: Put your trust in Apple’s machines and its native apps and everything will just work. There are no viruses, no blue screens of death, no pre-installed junkware popping up all over your brand-new desktop. Things just show up where they’re supposed to be. Mac’s user interface is so vastly superior to Windows’ that it seems ridiculous even to compare them. They’re both operating systems in the sense that the stick-shift on a Yugo and the flappy paddles on a Ferrari are both transmissions. Yet by 2015 one of Apple’s essential apps wasn’t just horrid to look at and baffling to use — it couldn’t even store and play people’s MP3s properly.

I never experienced the horror stories myself; [lucky bastard!] the idea of buying music from Apple and, because of its aggressive digital rights management, not even getting an MP3 file with which I could do what I liked always struck me as daft. But the Internet is full of tales of woe from people who entrusted their music collections to Apple and got royally screwed. iTunes would make curatorial decisions all by itself: If you bought Neil Young’s 1977 compilation album Decade, but already had On the Beach in your library, it might just decide not to include Walk On and Tired Eyes on your version of Decade. Or it might delete them from On the Beach, depending on its mood.

This was presumptuous and annoying, but at least somewhat explicable: iTunes consumers were far more singles-focused than album-focused. (Indeed the app is widely credited with ending the “age of the album.”) Less explicable were reports of Apple Music replacing people’s legacy music collections — songs they had ripped from CDs and entrusted to iTunes — with new downloads. People spoke of entire collections being corrupted or lost overnight. People reported that their libraries looked nothing alike on their various Apple devices. At one point, apparently under the impression that not many people loathe U2, Apple famously went ahead and beamed one of the band’s new snorefests onto everyone’s iTunes without asking.

My experiences with iTunes have been mostly of the minor irritant variety: disappearing songs, paid-for tracks that refused to play on certain devices, and songs showing up in playlists that they don’t belong to, for example. But at least — most of the time — the non-Apple songs were not randomly deleted from my library. Not too often, anyway.

May 15, 2019

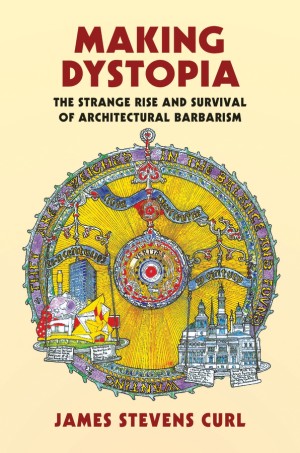

Modern architecture as a generations-long art crime spree

Theodore Dalrymple is clearly quite a fan of Making Dystopia: The Strange Rise and Survival of Architectural Barbarism by James Stevens Curl, as this is at least the third review of the book I’ve seen by him (and you can probably tell I agree with much of his viewpoint that I’m blogging it yet again…)

In a recent debate in Prospect magazine on the question of whether modern architecture has ruined British towns and cities, Professor James Stevens Curl, one of Britain’s most distinguished architectural historians, wrote as his opening salvo:

Visitors to these islands who have eyes to see will observe that there is hardly a town or city that has not had its streets — and skyline — wrecked by insensitive, crude, post-1945 additions which ignore established geometries, urban grain, scale, materials, and emphases.

This is so self-evidently true that I find it hard to understand how anyone could deny it, but modern architects and hangers-on such as architectural journalists do deny it, like war criminals who, for obvious reasons, continue to deny their crimes in the face of overwhelming evidence.

This is true not only of Britain but of many, perhaps most, other countries that have or had any towns or cities to ruin. Anyone who rides into the center of Paris from Charles de Gaulle Airport, for example, will be appalled at the modernist visual hell that scours his eyes as he goes.

Nor is this visual hell the consequence of the need to build cheaply. Where money is no object, contemporary architects, like the sleep of reason in Goya’s etching, bring forth monsters. The Tour Montparnasse (said to be the most hated building in Paris), the Centre Pompidou, the Opéra Bastille, the Musée du quai Branly, the new Philharmonie, do not owe their preternatural ugliness to lack of funds, but rather to the incapacity, one might say the ferocious unwillingness, of architects to build anything beautiful, and to their determination to leave their mark on the city as a dog leaves its mark on a tree.

Professor Curl’s magnum opus is both scholarly and polemical. He has been observing the onward march of modernism and its effects for sixty years and is justifiably outraged by it. British architects have managed to reverse the terms of the anarchist Bakunin’s dictum that the urge to destroy is also a creative urge: Their urge to create is also a destructive urge. I could give many concrete examples (no pun intended).

Curl knows that he is arguing not against an aesthetic, but against an ironclad ideology. The architectural Leninists have been determined so to indoctrinate the public that they hope and expect a generation will grow up knowing nothing but modernism, and therefore will be unable to judge it. (All judgment is comparative, as Doctor Johnson said.) In Paris recently, I saw an advertisement on the Métro (a few days before the fire in Notre-Dame) to the effect that Paris would not be Paris without the Centre Pompidou — which, of course, has a good claim to be the ugliest building in the world. In the face of such an advertisement promoted by the cultural elite, what ordinary person would dare demur?

Centre Georges-Pompidou (no, this isn’t an under construction image … it’s from 2017 and the construction was technically complete in 1977)

Gerd Eichmann photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Could anyone imagine a worldwide outpouring of genuine and heartfelt grief, such as that which greeted the burning of Notre-Dame de Paris, if any building of the last seventy years burnt down? Indeed, the destruction of many would be a cause almost for rejoicing. Modernist buildings will never age as Notre-Dame aged; they will merely deteriorate, and usually do deteriorate even before completion.

May 5, 2019

Theresa May’s awful “Withdrawal” Agreement

Hector Drummond relays a Spectator article that lists 40 problems with Prime Minister May’s agreement with the EU:

Just in case readers don’t have the time to go through the lengthly document themselves, Steerpike has compiled a list of the top 40 horrors lurking in the small print of Theresa May’s Brexit deal.

[…]

In summary: The supposed “transition period” could last indefinitely or, more specifically, to an undefined date sometime this century (“up to 31 December 20XX”, Art. 132). So while this Agreement covers what the government is calling Brexit, what we in fact get is: “transition” + extension indefinitely (by however many years we are willing to pay for) + all of those extra years from the “plus 8 years” articles.

Should it end within two years, as May hopes, the UK will still be signed up to clauses keeping us under certain rules (like VAT and ECJ supervision) for a further eight years. Some clauses have, quite literally, a “lifetime” duration (Art.39). If the UK defaults on transition, we go in to the backstop with the Customs Union and, realistically, the single market. We can only leave the transition positively with a deal. But we sign away the money. So the EU has no need to give us a deal, and certainly no incentive to make the one they offered “better” than the backstop. The European Court of Justice remains sovereign, as repeatedly stipulated. Perhaps most damagingly of all, we agree to sign away the rights we would have, under international law, to unilaterally walk away. Again, what follows relates (in most part) for the “transition” period. But the language is consistent with the E.U. imagining that this will be the final deal.

The top 40 horrors:

- From the offset, we should note that this is an EU text, not a UK or international text. This has one source. The Brexit agreement is written in Brussels.

- May says her deal means the UK leaves the EU next March. The Withdrawal Agreement makes a mockery of this. “All references to Member States and competent authorities of Member States…shall be read as including the United Kingdom.” (Art 6). Not quite what most people understand by Brexit. It goes on to spell out that the UK will be in the EU but without any MEPs, a commissioner or ECJ judges. We are effectively a Member State, but we are excused – or, more accurately, excluded – from attending summits. (Article 7)

- The European Court of Justice is decreed to be our highest court, governing the entire Agreement – Art. 4. stipulates that both citizens and resident companies can use it. Art 4.2 orders our courts to recognise this. “If the European Commission considers that the United Kingdom has failed to fulfil an obligation under the Treaties or under Part Four of this Agreement before the end of the transition period, the European Commission may, within 4 years after the end of the transition period, bring the matter before the Court of Justice of the European Union”. (Art. 87)

- The jurisdiction of the ECJ will last until eight years after the end of the transition period. (Article 158).

- The UK will still be bound by any future changes to EU law in which it will have no say, not to mention having to comply with current law. (Article 6(2))

And on for another 35 awful items.

March 3, 2019

Yet another “adventure” in modern architecture

Or maybe the photographer is that Russian guy who did the greatest blog post of all time, just dragging Ottawa over thirty miles of bad road. He’s come back for a sequel

— Colby Cosh (@colbycosh) March 2, 2019

Thread reader can’t piece together unrelated-by-Twitter-standards tweets, so here’s the rest of that thread in one go:

Tank Chats #43 Matilda I | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published on 22 Dec 2017Development of Matilda I began in 1935. Production began just before the outbreak of the Second World War in July 1939 and 139 vehicles were delivered by August 1940. 97 of these were lost after the evacuation of troops from Dunkirk, without having had much use. The rest were removed from British service in 1941, but captured vehicles stayed in German service in domestic security roles.

Support the work of The Tank Museum on Patreon: ► https://www.patreon.com/tankmuseum

Or donate http://tankmuseum.org/support-us/donateVisit The Tank Museum SHOP: ►https://tankmuseumshop.org/

Twitter: ► https://twitter.com/TankMuseum

Tiger Tank Blog: ► http://blog.tiger-tank.com/

Tank 100 First World War Centenary Blog: ► http://tank100.com/ #tankmuseum #tanks

February 17, 2019

Tank Chats #42 Elefant | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published on 18 Aug 2017Originally known as the Ferdinand, then later renamed Elefant, 90 of this heavily armed and armoured vehicle were built, seeing service in the Soviet Union, Italy and Germany.

Although deployed as a tank destroyer, the Elefant had its origins in Ferdinand Porsche’s attempt to build what became the Tiger tank.

This particular Elefant is part of The Tiger Collection at The Tank Museum, Bovington, on loan from the US Army Ordnance Training and Heritage Center, VA.

Support the work of The Tank Museum on Patreon: ► https://www.patreon.com/tankmuseum

Or donate http://tankmuseum.org/support-us/donateTwitter: ► https://twitter.com/TankMuseum

Tiger Tank Blog: ► http://blog.tiger-tank.com/

Tank 100 First World War Centenary Blog: ► http://tank100.com/ #tankmuseum #tanks #tigertank tiger tanks tank chat

February 10, 2019

A debate on the impact of Brutalism on British cities

In Prospect magazine, James Stevens Curl and Barnabas Calder disagree on how Brutalist architecture has influenced destroyed urban areas in so many British cities. This is Curl’s opening salvo:

20 Fenchurch Street in London has been nicknamed the “Walkie-Talkie” due to its distinctive design.

Image by Toa Heftiba via Wikimedia Commons.

Visitors to these islands who have eyes to see will observe that there is hardly a town or city that has not had its streets — and skyline — wrecked by insensitive, crude, post-1945 additions which ignore established geometries, urban grain, scale, materials, and emphases.

Such structures were designed by persons indoctrinated in schools of architecture in ways that made them incapable of creating designs that did not cause immense damage and offend the eye, the sensibilities, and the spirit. Harmony with what already exists has never been a consideration for them, as it was not for their teacher: following the lead of “Le Corbusier” (as Swiss-French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret called himself), they have, on the contrary, done everything possible to create buildings incompatible with anything that came before. It seems that the ability to destroy a townscape or a skyline was the only way they have been able to make their marks. Can anyone point to a town in Britain that has been improved aesthetically by modern buildings?

Look at the more recent damage done to the City of London, with such crass interventions as the so-called “Walkie-Talkie” (which, through its reflectivity, has caused damage on the street below), or the repellent stuff inflicted on several cities by the infamous John Poulson and some of his bent cronies (from the 1950s until they were jailed in 1974). Quod erat demonstrandum.

How has this catastrophe been allowed to happen? A series of totalitarian doctrinaires reduced the infinitely adaptable languages of real architecture to an impoverished vocabulary of monosyllabic grunts. Those individuals rejected the past so that everyone had to start from scratch, reinventing the wheel and confining their design clichés to a few banalities. Today, form follows finance, when modern architecture is dominated by so-called “stars,” and becomes more bizarre, egotistical, unsettling, and expensive, ignoring contexts and proving stratospherically remote from the aspirations and needs of ordinary humanity. Their alienating works, inducing unease, are, without exception, inherently dehumanising and visually repulsive.

February 6, 2019

“The haggis croquette is the most London-thing ever done in London”

At the IEA, Andy Mayer reports on the first attempted Burns Night Supper in the City of London:

Haggis is a traditional Scottish dish made with sheep’s heart, liver and lungs, and stomach (or sausage casing); onion, oatmeal, suet, and spices. It’s either a local delicacy or an elaborate joke played on the English (take your pick).

Photo by “Lordvolom1” via Wikimedia Commons.

Last week the City of London held their first attempt at a Burns night supper, with the First Minister and representatives of the Scottish Government as guests of honour.

It is a difficult tradition to get wrong. Largely it requires steaming piles of Scotland’s revenge on the sausage, poetry that the English politely pretend to understand while feeling vaguely threatened, and bonhomie to overcome it, enabled through litres of distillate infused with the flavour of an entire peat bog.

The City served haggis croquettes, with wine.

There’s possibly a Glaswegian satirist somewhere who’s just given up. “Ach I canne compete. The sassenach dough-monkeys just served wee Nicola a haggis croquette, on Rabbie Burns night! I’m breaking-me pen.”

Meanwhile in Shoreditch two Millenials have just set up the Haggis Croquette Cafe, serving Organic Iron-Bru made from recycled plastic girders. The haggis croquette is the most London-thing ever done in London.

I spent much of the evening talking to trade officials. Their job is to sell Scottish opportunity around the world and open up its markets.

This was interesting – how would descendants of Adam Smith visiting the birthplace of trade economist David Ricardo define their comparative advantage? What can Scotland do better than anyone else? What might they do well enough that they can carve out positions, despite larger rivals, better off leaving such things to Scotland? Fundamentally, how are they going to compete?

There was an uneasy pause after these questions. And then to paraphrase, “Oh no, we don’t want to compete, we want to cooperate! With everyone! Not being threatening, that’s our advantage!”

I feel very sure that Smith, on hearing this, would have reached out, to extend the invisible hand of history across time, to give this official a mild slap. “Encouraging competition, with and from other places, and then getting out of the way, is the whole point”, he might say.

February 2, 2019

Curing Tuberculosis – The Hero Koch – Extra History – #1

Extra Credits

Published on 31 Jan 2019Fascinatingly enough, tuberculosis was actually considered “trendy” in the Victorian era of Europe — but Dr. Robert Koch, hero of the German Empire, was convinced that he could cure it. A British writer named Arthur Conan Doyle, however, was a little skeptical, and for good reason…

Enjoy today’s extra-Extra History! Dr. Robert Koch was going to save Germany, and the rest of Europe, from tuberculosis. Maybe he would even get his own institute, like his medical rival Louis Pasteur. He knew for sure he was on to something…

Join us on Patreon! http://bit.ly/EHPatreon

January 30, 2019

QotD: Political memoirs

We’re told not to judge books by their covers, but faced with these two it’s hard not to. Harman’s is one of those thick, expensive tomes which, understandably, politicians write when they’ve had enough earache and, unbelievably, publishers keep buying for vast sums, despite the fact that a fortnight after publication you can pick them up cheaper than an adult colouring book in a remainder bin. The old saw that ‘all political careers end in failure’ might now better be: ‘All political careers end with a book on Amazon going for less than the price of the postage.’

Julie Burchill, “Harriet Harman and Jess Phillips: poles apart in the sisterhood”, The Spectator, 2017-02-25.