Fortunately, as Tim Worstall explains, politicians can rarely be believed — especially when it comes to economics:

Hillary Clinton Vows To Slam The Economy Into Recession Immediately Upon Election

This probably isn’t quite what Hillary Clinton intended to say but it is what she did say at a fundraiser on Friday night. That immediately upon election she would slam the US economy into a recession. For what she has said is that she’s not going to add a penny to the national debt. Which, in an economy running a $500 billion and change budget deficit means tax rises and or spending cuts of $500 billion and change immediately she takes the oath. And that’s a large enough and fierce enough change, before she does anything else, to bring back a recession.

[…]

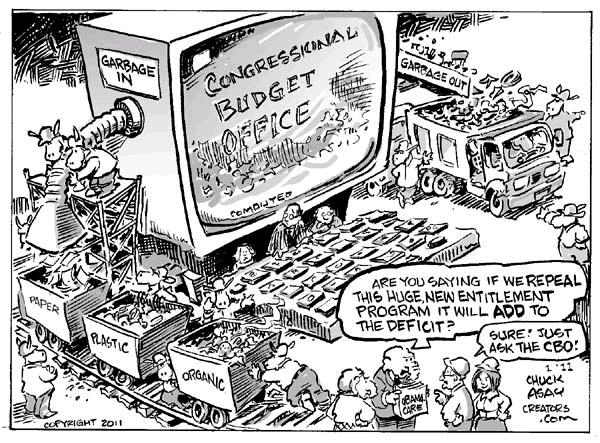

Now, what she meant is something more like this. That she has some spending plans, which she does. And she is also proposing some tax rises. And that her tax rises will balance her spending plans and thus the mixture of plans will not increase the national debt. Which is possibly even true although I don’t believe a word of it myself. For her taxation plans are based upon static analyses when we really must use dynamic ones to measure tax changes. This is normally thought of as something that the right prefers. For if we measure the effects of tax cuts using the dynamic method then there will be some (please note, some, not enough for the cuts to pay for themselves) Laffer Effects meaning that the revenue loss is smaller than that under a static analysis. But this is also true about tax rises. Behaviour really does change when incentives change. Thus tax rises gain less revenue in real life than what a straight line or static analysis predicts.

That is, as I say, probably what she means. But that’s not actually what she said. She said she’ll not add a penny to the national debt. Which means that immediately on taking office she’s got to either raise taxes by $500 billion and change or reduce spending by that amount. Because the budget deficit is that $500 Big Ones and change at present and the deficit is the amount being added to the national debt each year. The problem with this being that that’s also some 3.5% or so of GDP and an immediate fiscal tightening of that amount would put the US economy back into recession.