I think it’s a mistake to worry too much about what is “normal”. “Normal” men in patriarchal societies tend to want their wives to dress in a way they perceive as modest; this derives from a desire to protect their “property” from those who might trespass or steal it. The more patriarchal the society, the more “modestly” it expects women to dress; in societies where women’s status is higher, women tend to dress more provocatively, and in those where it is lower, they tend to dress more concealingly. There are few if any exceptions, yet neofeminists teach a looking-glass version of reality in which dressing sexily is “objectification” and a manifestation of “patriarchy”, despite abundant real-world evidence that the exact opposite is true. Now, this is not to say that one individual man, or indeed large minorities of men, might not prefer women who “belong” to them dressed in a revealing fashion; however, the majority (“normal”) view has always been the opposite.

Maggie McNeill, “Wardrobe Choices”, The Honest Courtesan, 2014-10-08.

September 22, 2015

QotD: Women’s clothing in patriarchal cultures

March 21, 2015

QotD: The modern snob

Walking through Amsterdam recently, a paradox that I had long noticed in an inchoate way formulated itself clearly in my mind. It was this: A century ago, there would have been one clothes shop for every hundred well-dressed people. Nowadays there is one well-dressed person (if that) for every hundred clothes shops. What accounts for this strange reversal of ratios?

Beyond the fact that clothes are now mass-produced rather than made individually, there is an act of will involved. Practically everyone now dresses not merely in a casual way, but with studied slovenliness for fear of being thought elegant, as elegance is a metonym for undemocratic sentiment or belief. You can dress as expensively as you like, indeed expensive scruffiness is a form of chic, but on no account must you dress with taste and discrimination. To do so might be to draw hostile attention to yourself. Who on Earth do you think you are to dress like that?

[…]

Modern scruffiness, then, is a manifestation of egotism. Outside one of the shops in Amsterdam was a large plasma screen showing models wearing the kind of clothes to be had within. They were precisely the insolently ragged clothes that the great majority of people in the street were wearing anyway. This was a form of flattery of the public, for it implied that its members had nothing to aspire to in the matter of dress higher than that which they themselves were already wearing — that in the matter of appearance they had already reached acme of the possible.

There was yet more. The models, in their T-shirts, baseball caps, sneakers, and so forth, as uniform as any army, walked with the kind of vulpine lope that one associates with the less law-abiding young males of the American ghettoes. But even more striking was the expression on their faces, which were cachectic in the case of the women, androgynous in the case of men: a fixed, determined, humorless stare that indicated a hatred of the world and all that was in it, including their fellow-beings. If one saw such a person at a social event, one would go to some effort to avoid or to flee or not to talk to him or her. The models’ faces were vacantly earnest, as if they wished for annihilation of everything around them for some personal reason, no doubt trifling.

This is the first age in which people do not dress to please others, but dress to displease others, to make sure that everyone knows that I’m not going to make any effort just for you. And this, no doubt, is because I am as good as anyone in the world, bar none: His Majesty, myself. And what starts out as an attitude becomes an unexamined and ingrained habit.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Slobbery as Snobbery”, Taki’s Magazine, 2014-06-15.

December 14, 2014

New BBC historical TV series as accurate as possible … except for the codpieces being “too small”

Apparently, the fear was that US TV audiences would be shocked by authentic sized boasting pieces:

They may have been the crowning glory for any right-thinking Tudor gentleman, but it appears the traditional codpiece may be a little too much for American television viewers.

The stars of Wolf Hall, the BBC’s new period drama based on the novels of Hilary Mantel, have disclosed they have been issued with “smaller”-than average codpieces, out of respect for viewers’ sensibilities.

Mark Rylance, who stars as Thomas Cromwell in the forthcoming BBC series, said programme-makers had decided on “very small codpieces” which had to be “tucked away”.

He suggested allowances had been made amid concerns about the taste of modern audiences, particularly in America, who “may not know exactly what’s going on down there”.

It is one of few concessions permitted by programme-makers, who have otherwise gone to remarkable lengths to ensure historical accuracy, including trips to Shakespeare’s Globe to learn sword-fighting, lessons in etiquette and bowing, and a comprehensive study on spoons.

Mantel has given her seal of approval to the production, issuing a statement of glowing praise for how it has been adapted on screen.

Saying she was pleased programme-makers had resisted the temptation to “patronise” the Tudors to make them “cute”, she said: “My expectations were high and have been exceeded.”

When asked about the costumes in a Q&A to launch the BBC show, alongside actors Damian Lewis and Claire Foy, Rylance said they “did take a while to put on” but praised the overall effect.

“I think the codpieces are too small,” he added. “I think it was a direction from our American producers PBS [the US public service broadcaster] – they like very small codpieces which always seemed to be tucked away.”

When asked to clarify, he said: “I wasn’t personally disappointed by the codpieces: I’m a little more used to them than other people from being at the Globe for ten years.

“But I can see for modern audiences, perhaps more in America, they may not know exactly what’s going on down there.”

H/T to David Stamper for the link(s).

November 20, 2014

Fortunately, T-shirts aren’t as permanent as tattoos

If you’re of a skeptical turn, you may have wondered just what your friend’s new tattoo really says in Chinese, or Russian, or whatever script their tattoo artist just inked into their skin. My suspicion is that at least a significant proportion of the new ‘tats are the equivalent of these Japanese discount store shirts with random English words:

Reddit user k-popstar recently moved to Japan to teach English. Over the last few months he has been wandering into various discount stores and taking photos of shirts with random English words on them. I have to admit, that potato one is pretty sweet!

That second one is almost poetic. If I knew what “thirstry” was.

H/T to Coyote Blog for the link.

October 27, 2014

The invention of the suit

A.A. Gill had an unplanned meeting with British Labour Party leader, but the article isn’t about the politician himself, it’s about his suit:

Suits are malevolent magicians’ sleeves for socialists, full of patrician loops and tricks, small, embroidered, cryptic messages of deference and privilege. They are ever the uniform of the enemy. They are also the greatest British invention ever. That’s not hyperbole or jingotastic boasting. It’s the plain, double-breasted truth. Nothing else that comes from this pathetically stunted island has had anything like the universal acceptance, reach or influence of the suit.

Look at it as if you’d never seen one before. Nothing about it makes sense. It’s not practical; it’s not particularly comfortable; it doesn’t work; it’s not decorative; and it doesn’t make us look good, rather like the establishment it represents. And, like most things in this place, it arrived through a series of accidents, mistakes, misinterpretations, good intentions, conventions and slovenliness, all of it growing out of radicalism.

The suit is the polite taming, the socialising, the neutering, of riding and military kit. Those pointless buttons on the cuff were moved from lateral to vertical. You used to be able to fold the end of your sleeve over and forward and button it like a mitten, for riding in the cold. Incidentally, the buttons on the cuff should correspond to the number of buttons on the front, not for any practical reason, but just because that’s what they should do. The vents at the back are made for sitting on a horse. The slanting pockets are for easy access when mounted. The suit that we wear was, in essence, invented by Beau Brummell – an obsessive, highly strung, socially insecure, thin-skinned aesthete, snob and genius. And, of course, an Etonian. He wanted to simplify the extraordinarily otiose decorative court dress to give men an elegant line. When the bailiffs finally broke into his rooms, they found only a simple deal table with a note that said, archly, “Starch is everything.” Beau escaped to France, where people said he looked like an Englishman and he died in an asylum.

We have to thank the members of the Romantic movement for the sober colours of suits. It was their love of the Gothic that put us in grey and black but the suit stuck. It said something and it meant something to men around the world; it said and meant so much that they would discard their local dress, the costumes of millennia, their culture and their link to their ancestors, to dress up like English insurance brokers. There is not a corner of the world where the suit is not the default clobber of power, authority, knowledge, judgement, trust and, most importantly, continuity. The curtained changing rooms of Savile Row welcome the naked knees of the most despotic and murderous, immoral and venal dictators and kleptocrats, who are turned out looking benignly conservative, their sins carefully and expertly hidden, like the little hangman’s loops under their lapels.

October 14, 2014

A new view on cosplay – as a symptom of a seriously weakened economy

A certain amount of this rings true:

Imagine you’re a college graduate stuck in a perpetually lousy economy. That’s a problem Japanese twenty-somethings have faced for more than 20 years. Two decades of stagnation after the collapse of the 1980s real-estate and stock bubbles — combined with labor laws making it tough to fire older workers — have relegated vast numbers of Japanese young adults to low-paying, temporary contract jobs. Many find themselves living with their parents well into their twenties and beyond, unmarried and childless.

Then again, they do have plenty of time to dress up like wand-wielding sailor girls and cybernetic alchemist soldiers from the colorful world of anime cartoons and manga comics. Indeed, Japan’s Lost Decades have coincided with a major spike in “people escaping to virtual worlds of games, animation, and costume play,” Masahiro Yamada, a sociology professor at Chuo University in Tokyo, recently told the Financial Times. “Here, even the young and poor can feel as though they are a hero.”

It’s hard to blame them. After all, it’s not that these young adults in Japan are resisting becoming productive members of the economy — it’s that there just aren’t enough opportunities for them. So an increasingly large number of them spend an increasingly large amount of time living in make-believe fantasy worlds, pretending they are someone else, somewhere else. This is a very bad thing for the Japanese economy.

And guess what: America has a growing number of make-believe “cosplay” heroes, too. Many of the 130,000 people who attend the San Diego Comic Con every year invest big bucks in elaborate outfits as a way of showing off their favorite Japanese characters, as well as those from American superhero movies, comics, and “genre” televisions shows such as Game of Thrones. And this trend is growing — the crowd at Comic Con was one-third this size in 2000. In 2013, the SyFy channel even created a reality show about the trend, Heroes of Cosplay.

H/T to Ghost of a Flea for the link.

October 2, 2014

The Aral Sea, Uzbek cotton, forced labour, and the clothing industry

As reported the other day, what was once the world’s fourth largest lake, the Aral Sea, has almost completely dried up due to Soviet water diversion projects of the late 1950s and early 1960s:

In the early 1960s, the Soviet government decided the two rivers that fed the Aral Sea, the Amu Darya in the south and the Syr Darya in the east, would be diverted to irrigate the desert, in an attempt to grow rice, melons, cereals, and cotton.

This was part of the Soviet plan for cotton, or “white gold”, to become a major export. This temporarily succeeded, and in 1988, Uzbekistan was the world’s largest exporter of cotton.

The Soviet government made a deliberate choice to sacrifice the Aral Sea to create a vast new cotton-growing region in Uzbekistan. It was clearly quite successful, depending on how you choose to measure success.

The disappearance of the lake was no surprise to the Soviets; they expected it to happen long before. As early as 1964, Aleksandr Asarin at the Hydroproject Institute pointed out that the lake was doomed, explaining, “It was part of the five-year plans, approved by the council of ministers and the Politburo. Nobody on a lower level would dare to say a word contradicting those plans, even if it was the fate of the Aral Sea.”

The reaction to the predictions varied. Some Soviet experts apparently considered the Aral to be “nature’s error”, and a Soviet engineer said in 1968, “it is obvious to everyone that the evaporation of the Aral Sea is inevitable.”

The drying-out of the Aral was not just bad news for the fishermen of the region: it was a full-blown environmental disaster, as the former lake bottom was heavily polluted:

The receding sea has left huge plains covered with salt and toxic chemicals – the results of weapons testing, industrial projects, and pesticides and fertilizer runoff – which are picked up and carried away by the wind as toxic dust and spread to the surrounding area. The land around the Aral Sea is heavily polluted, and the people living in the area are suffering from a lack of fresh water and health problems, including high rates of certain forms of cancer and lung diseases. Respiratory illnesses, including tuberculosis (most of which is drug resistant) and cancer, digestive disorders, anaemia, and infectious diseases are common ailments in the region. Liver, kidney, and eye problems can also be attributed to the toxic dust storms. Health concerns associated with the region are a cause for an unusually high fatality rate amongst vulnerable parts of the population. The child mortality rate is 75 in every 1,000 newborns and maternity death is 12 in every 1,000 women. Crops in the region are destroyed by salt being deposited onto the land. Vast salt plains exposed by the shrinking Aral have produced dust storms, making regional winters colder and summers hotter.

The Aral Sea fishing industry, which in its heyday had employed some 40,000 and reportedly produced one-sixth of the Soviet Union’s entire fish catch, has been devastated, and former fishing towns along the original shores have become ship graveyards. The town of Moynaq in Uzbekistan had a thriving harbor and fishing industry that employed about 30,000 people; now it lies miles from the shore. Fishing boats lie scattered on the dry land that was once covered by water; many have been there for 20 years.

“Waterfront” of Aralsk, Kazakhstan, formerly on the banks of the Aral Sea. Photo taken Spring 2003 by Staecker. (Via Wikipedia)

So, tragic as all this is, what does it have to do with the clothing industry? The Guardian‘s Tansy Hoskins points out that due to the murky supply chains, it’s almost impossible to find out where the cotton used by many international clothing firms actually originates, and the Uzbek cotton fields are worked by forced labour:

The harvest of Uzbek cotton is taking place right now — it started on the 5 September and is expected to last until the end of October. The harvest itself is also a horror story, on top of the environmental devastation, this is cotton picked using forced labour. Every year hundreds of thousands of people are systematically sent to work in the fields by the government.

Under pressure from campaigners, in 2012, Uzbek authorities banned the use of child labour in the cotton harvest, but it is a ban that is routinely flouted. In 2013 there were 11 deaths during the harvest (pdf), including a six year old child, Amirbek Rakhmatov, who accompanied his mother to the fields and suffocated after falling asleep on a cotton truck.

Campaigners have also managed to get 153 fashion brands to sign a pledge to never knowingly use Uzbek cotton. Anti-Slavery International have worked on this fashion campaign but acknowledge that despite successes there is still a long way to go.

“Not knowingly using Uzbek cotton and actually ensuring that you don’t use Uzbek cotton are two completely different things,” explains Jakub Sobik, press officer at Anti-Slavery International.

One major problem that Sobik points out is that much of the Uzbek cotton crop now ends up in Bangladesh and China — key suppliers for European brands. “Whilst it is very hard to trace the cotton back to where it comes from because the supply chain is so subcontracted and deregulated, brands have a responsibility to ensure that slave picked cotton is not polluting their own supply chain.”

September 16, 2014

Coming to Kickstarter real soon now…

Frequent commenter Lickmuffin sent me a message that I thought was amusing enough to promote to a full post:

Speaking of writing like someone else, your Three Men In A Boat posts made me read that work and the similar-in-style Leacock. I’m starting work on a Sunshine Sketches-like book updated for modern times: Oxycontin Delusions of a Ditchpig Trailer Park.

That’s the working title — I’ll clean it up when I set things up on Kickstarter.

Speaking of Kickstarter, the wife wants to start a My Daughter Is Not A Skank campaign there to see if we can get some decent girls’ clothing manufactured. Went shopping on the weekend for the first time in a long time and it was kinda scary to see what’s being marketed to pre-teen girls. Most retailers only have two jean styles available for girls: Boot Cut and Skinny. In terms of actual cut and fit, they are identical. Old Navy is the only retailer with a third option: Boyfriend Skinny. Actually, that’s not quite true — Sears also offers a style called Mommy’s Little Money Maker.

I’m thinking that burkas actually make a lot of sense.

April 9, 2014

The rise of the bloodmouth carnists

ESR has a bit of fun at the expense of a militant vegan:

Some weeks ago I was tremendously amused by a report of an exchange in which a self-righteous vegetarian/vegan was attempting to berate somebody else for enjoying Kentucky Fried Chicken. I shall transcribe the exchange here:

>There is nothing sweet or savory about the rotting

>carcass of a chicken twisted and crushed with cruelty.

>There is nothing delicious about bloodmouth carnist food.

>How does it feel knowing your stomach is a graveyardI’m sorry, but you just inadvertently wrote the most METAL

description of eating a chicken sandwich in the history of mankind.MY STOMACH IS A GRAVEYARD

NO LIVING BEING CAN QUENCH MY BLOODTHIRST

I SWALLOW MY ENEMIES WHOLE

ESPECIALLY IF THEY’RE KENTUCKY FRIED

I am no fan of KFC, I find it nasty and overprocessed. However, I found the vegan rant richly deserving of further mockery, especially after I did a little research and discovered that the words “bloodmouth” and “carnist” are verbal tokens for an entire ideology.

First thing I did was notify my friend Ken Burnside, who runs a T-shirt business, that I want a “bloodmouth carnist” T-shirt – a Spinal-Tap-esque parody of every stupid trash-metal tour shirt ever printed. With flaming skulls! And demonic bat-wings! And umlauts! Definitely umlauts.

Once Ken managed to stop laughing we started designing. Several iterations. a phone call, and a flurry of G+ messages later, we had the Bloodmouth Carnist T-shirt. Order yours today!

March 17, 2014

Tokenism watch – PhD models

Martha Gill is underwhelmed by Betabrand’s use of PhDs as runway clothing models:

‘Hey ladies, you might have PhDs, but really you all want to be models’

Is there no job you don’t need a ludicrous set of qualifications for nowadays? Clothing company PhD, in a fairly ill-defined attempt to, I don’t know, raise awareness or something, have hit upon a novel concept for a fashion shoot: recruiting only models with PhDs.

“Our designers cooked up a collection of smart fashions for spring, so why not display them on the bodies of women with really big brains?” founder Chris Lindland said in a statement. Supporters have greeted it as a feminist move, saying it helps to promote “different kinds of female role models”.

Hmmm. Does it? I’m really not so sure that it does.

[…]

I mean, I see what they’re trying to do. They are trying to broaden the public’s idea of models, make them more representative, and show that being intelligent is something to aspire to, too. They just haven’t managed to do this. In any way.

You see, what I think they’ve done here is confuse the term “role model” with “clothing model”. The drive to make models more “representative” (see also Dove’s “real women” campaign) is actually setting up modelling to be far more aspirational than it is. It takes as read that being a model is the pinnacle of feminine achievement, and all we need to do to make girls feel good about themselves is to tell them they, too, can all be models. Even if they’re PhD students.

But models are just models. Really, really, ridiculously good-looking people doing what, when it comes down to it, is a fairly crap job.

The photo chosen to accompany the article in the Telegraph is why I originally wrote “runway model” instead of “clothing model”. The photos in the Daily Mail taken from the Betabrand website are much less … ridiculous than the Telegraph implies. They’re just modelling ordinary clothing for ordinary women, not the weird and totally impractical stuff some clothing designers foist on their runway models at fashion shows.

I’d say there’s no story here (despite blogging about it), but there is. It’s just not quite the drive-by that the Telegraph‘s photo editor wants it to be. Betabrand scored a lot of free advertising and (probably) got its clothing line modelled on the cheap as well. It’s rather amusing that the Daily Mail is significantly more realistic in their coverage of this story than the Telegraph.

January 11, 2014

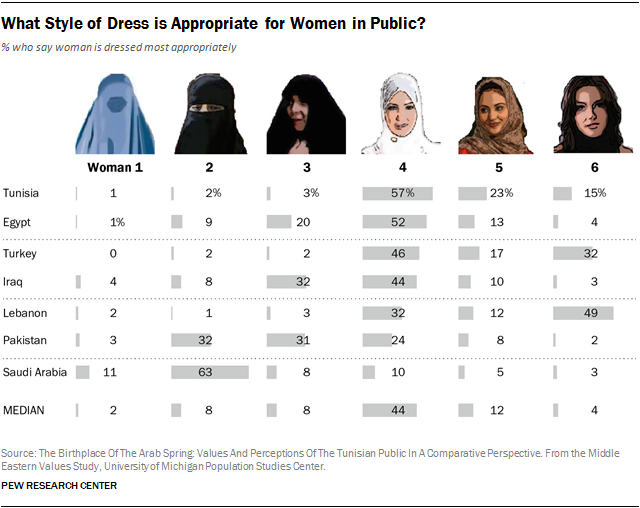

Poll on women’s head coverings in Islamic countries

From this graphic, you’d have to draw the conclusion that most people in Islamic nations are scandalized by the appearance of women’s hair:

An important issue in the Muslim world is how women should dress in public. A recent survey from the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research conducted in seven Muslim-majority countries (Tunisia, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Turkey), finds that most people prefer that a woman completely cover her hair, but not necessarily her face. Only in Turkey and Lebanon do more than one-in-four think it is appropriate for a woman to not cover her head at all in public.

The survey treated the question of women’s dress as a visual preference. Each respondent was given a card depicting six styles of women’s headdress and asked to choose the woman most appropriately outfitted for a public place. Although no labels were included on the card, the styles ranged from a fully-hooded burqa (woman #1) and niqab (#2) to the less conservative hijab (women #4 and #5). There was also the option of a woman wearing no head covering of any type.

Overall, most respondents say woman #4, whose hair and ears are completely covered by a white hijab, is the most appropriately dressed for public. This includes 57% in Tunisia, 52% in Egypt, 46% in Turkey and 44% in Iraq. In Iraq and Egypt, woman #3, whose hair and ears are covered by a more conservative black hijab, is the second most popular choice.

Update: Of course, no discussion of the oppression of women in other countries can be considered complete until we’ve managed to find an angle where Western culture is significantly worse:

Studies have found that the average woman in the UK spends £26,500 on her hair over her lifetime, with 25% of respondents saying they would rather spend money on their hair than food. And women don’t just spend serious money on their hair, they spend serious time on it. On average, British women spend just under two years of their lives styling their hair at home or in salons.

Whether it’s covered by a veil or coloured by Vidal Sassoon, hair is a feminist issue. Indeed, hair is so bound up with ideals of femininity that, to some degree, the measure of a woman is found in the length of her hair. In the semiotics of female sexuality, long hair is (hetero)sexual, short hair is non-sexual or homosexual, and no hair means you’re either a victim or a freak. When Natalie Portman shaved her head for a film role she summed up these stereotypes with the observation that: “Some people will think I’m a neo-Nazi or that I have cancer or I’m a lesbian.” But Portman also added: “It’s quite liberating to have no hair.”

[…]

In a sense, women’s hair in the west functions as it’s own sort of veil, one which most of us are unconsciously donning. The time and money women spend on their hair isn’t just the free exercise of personal preferences, it’s part of a broader cultural performance of what it means to be a woman; one that has largely been directed by men. Rather than fixating on what the veil means for Muslim women, then, we should probably spend a little more time thinking about our own homegrown veils. Because it’s still an unfortunate fact that, across the Muslim and non-Muslim world, women are often judged more by what is covering their head that what is in it.

November 15, 2013

Near-future investment advice – get out of retail clothing businesses

As Charles Stross makes clear in his most recent blog post, the way we buy clothes will be changing markedly in the near future:

Fabrican is a unlikely-sounding spin-off of the Department of Chemical Engineering, at Imperial College (which in case you’re not familiar with it is one of the top engineering/science colleges in the UK; formerly part of the University of London) — at least, it’s unlikely until you begin thinking in terms of emulsions, colloids, and the physical chemistry of nanoscale objects. It’s basically fabric in a spray can. Tiny fibres suspended in liquid are ejected through a fine nozzle and, as the supernatant evaporates, they adhere to one another. If at this point you’re thinking The Jetsons and spray-on clothing, have a cigar: you’ve fallen for the obvious marketing angle, because if you’re trying to market a new product and raise brand awareness among the public, what works better than photographs of serious-faced scientists with paint guns spray-painting hot-looking models with skin-tight instant leotards? (Note: the technical term for this sort of marketing gambit is, or really ought to be, bukake couture.)

[…]

What are the implications?

If you don’t think printing woven fabric is a big deal, DARPA beg to differ; DARPA is pumping serious money into robot sewing machines. But automating garment assembly from traditional fabric components turns out to be a really hard problem (as this possibly-paywalled New Scientist article on a €23M project to build a sewbot explains). Cloth is slippery, changes shape if you drop it, wrinkles, and has to be stretched and twisted and folded as it is sewn. Note that final word: sewn. If you can print fabric in situ out of fibres in a liquid form, you don’t need to sew components to shape—especially if you can print more than one type and colour of fibre at a time: you can fabricate your “stitches” (inter-layer connections) as part of the process, with minimal hand-finishing to possibly add fasteners (zips or buttons).

Add in a left-field extra: the rapid spread of millimeter wave scanners for airport security. These devices caused a bit of a to-do, earning them the nick-name “perv scanner” in some circles, because of their ability to see through clothing to the skin beneath, in order to check passengers for hidden contraband. But if you put the same machine in a clothes shop, it allows the establishment to obtain extremely accurate measurements of its customers without requiring a strip-tease and manual measurement of all the relevant saggy, lumpy bits and pieces. By use of surface-penetrating wavelengths (possibly high-intensity laser light, or infrared) it may also be possible to automatically distinguish between fatty tissue, musculature, and underlying bone structure. All of which are relevant to the construction of clothing.

So here’s my picture of the chain store of the future. You go in, go to the scanning booth, and do the airport-equivalent thing in a variety of positions — stretch and bend as well as hands-up. You then look at the styles on display on the shop floor, pick out what you like, and see it as it will appear on your own body on an avatar on a computer screen. You buy it, and a machine in the back of the store (or an out-of-town lights out 24×7 robotic garment factory) begins to print it. Some time later — maybe minutes, maybe hours or a day or two — the outfit you ordered comes to you. And it fits perfectly, every time. Some items are probably still off-the-shelf (socks, hosiery, maybe even those cheap tee shirts), but anything major is printed, unless you can afford to go to the really high end and pay a human being to make it for you out of natural fibres. Oh, and the printed stuff doesn’t have seams in places that chafe or bind.

September 16, 2013

“This is Britain. And in Britain you can wear what you want.”

In the Telegraph, Dan Hodges defends the right of women to wear whatever they want:

The debate about “The Veil”, is neither necessary, nor is it complex. In fact, it’s very, very simple. This is Britain. And in Britain you can wear what you want.

Obviously there are practical exceptions. I can’t turn up to my local swimming pool and jump in with my clothes on, for example. When I tweeted about this earlier today a number of people asked: what about people going through airport security? And in that instance obviously veils should be removed. In the same way that when I pass through security, my shoes occasionally have to be removed. But that doesn’t alter the basic fact that if I still want to wander round in my pair of battered Adidas Samba, I’m free to do so. And any women who wishes to wear a veil is free to do that too.

“You can’t wear hoodies in shopping centres, or crash helmets in banks”, some people have pointed out. Fair enough. When the nation is trembling from an onslaught of Burka-clad steaming gangs I may reassess my view. But until then the rule remains; we are a free society, and we are free to wear the clothing of our choice.

I understand those who express concern about the cultural implications of veils. Indeed, I share them. My wife and I regularly drive through Stamford Hill to see relatives. When we do, we invariably reflect on the local Hasidic Jewish community, and how great it is that London is so rich culturally. But it’s noticeable that all the women, (and indeed the men), are essentially dressed in the same way. That’s great to look at from the outside, and reflects a strong sense of heritage and identity. Yet it also reflects conformity. And conformity is a bad thing. It stifles personal identity, and by extension freedom.

But from my point of view, that’s just tough. If I were to advocate passing a law that said Hasidic Jewish women should be banned from going out unless they’re dressed in bright, vibrant colours, I’d rightly be regarded as having lost my mind. And it’s no different to advocating we should start punishing women who decide to go out in a veil.

September 15, 2013

Back to school shopping fails to rescue the clothing chains

We all spent less than we were supposed to last quarter, and the clothing business is feeling tight:

Fantasies about a strong back-to-school shopping season had already gotten slammed when teen retailer American Eagle Outfitters, back in August, chopped its second-quarter earnings in half and confessed to lousy sales — down 2% overall and 7% on a comparable-store basis. CEO Robert Hanson blamed weak traffic and women who hadn’t bought enough of the stuff on the shelf. “The domestic retail environment remains challenging,” he concluded.

Competitor Abercrombie & Fitch reported its quarterly results the same day. While total sales were down “only” 1% year over year, booming international sales — up 15% overall and up 60% in China on a comparable store basis — papered over a debacle in the US, where sales plunged 8%. CEO Michael Jeffries summed up the US phenomenon: a “challenging environment,” “weaker traffic,” and “softness in the female business.” While “consumers in general” might be feeling better, he ventured, “that’s not the case for the young consumer.”

Alas, by today, his “consumers in general” had gotten the blues too, according to the University of Michigan/Thomson Reuters consumer-sentiment index. It plunged from 82.1 in August to 76.8 in September, the lowest since April. “Economists” on average had expected a flat 82 — they don’t get out much, do they? Particularly brutal was the collapse of the economic outlook index from 73.7 to 67.2, the lowest since January. So, a retail recovery in the second half? Maybe not so much.