Practical Engineering

Published 29 Oct 2018Comparing modern concrete to that of the western Roman empire.

In this video, I discuss a few modern techniques that help improve design life of concrete, including roller compacted concrete (RCC) and water reducing admixtures (superplasticizers). There are a whole host of differences between modern concrete and that of the western Roman empire that I didn’t have time to go into, including freeze/thaw damage. This is such an interesting topic, so here are some references if you’d like to learn more:

– http://www.romanconcrete.com/

– https://www.usbr.gov/tsc/techreferenc…

– https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_c…-Patreon: http://patreon.com/PracticalEngineering

-Website: http://practical.engineeringTonic and Energy by Elexive is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6fBP…

August 2, 2020

Was Roman Concrete Better?

February 11, 2020

Hydrogen – the Fuel of the Future?

Real Engineering

Published 20 Apr 2018Thank you to Shell for sponsoring this video. Listen to the Intelligence Squared Podcast for more: https://www.intelligencesquared.com/i…

Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/brianjamesm…Additional Reading: https://go.shell.com/2qLmhWv

Get your Real Engineering merch at: https://standard.tv/collections/real-…

Patreon:

https://www.patreon.com/user?u=282505…

Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/brianjamesm…

Twitter:

https://twitter.com/FiosrachtMy Patreon Expense Report:

https://goo.gl/ZB7kvKThank you to my patreon supporters: Adam Flohr, darth patron, Zoltan Gramantik, Henning Basma, Karl Andersson, Mark Govea, Mershal Alshammari, Hank Green, Tony Kuchta, Jason A. Diegmueller, Chris Plays Games, William Leu, Frejden Jarrett, Vincent Mooney, Ian Dundore, John & Becki Johnston. Nevin Spoljaric, Kedar Deshpande

Music:

“Sydney Sleeps Alone Tonight” by eleven.five & Dan Sieg [Silk Music]

“Hydra” by Huma-Huma, and “Dawn” by Andrew Odd [Silk Music]

Silk Music: http://bit.ly/MoreSilkMusic

January 4, 2020

Looking back at the ’20s … the 1620s

In the latest installment of Anton Howes’ Age of Invention, he takes us back to what he calls the “transformative 20s” of the seventeenth century:

St. Paul’s Church in Covent Garden (built 1631-8) by Inigo Jones.

Photo by Steve Cadman via Wikimedia Commons.

The 1620s saw an upsurge in major projects to transform Britain’s landscape. Engineers from the Dutch Republic like Cornelius Vermuyden came to straighten its rivers, build canals, and even drain its marshes, converting them into pasturage and farmland — in the decades that followed, they would even begin to drain the Great Fens. The cityscapes changed too. The former theatre designer and architect Inigo Jones — by 1615 the Surveyor-General of the King’s Works — introduced classical architecture from the continent, drawing upon the rules of beauty and proportion that had been set down by Vitruvius in the first century BCE and resuscitated in Renaissance Italy by Andrea Palladio. Jones’s influence transformed England’s palaces, churches, cathedrals, and even Covent Garden square, to reflect his ancient Roman ideal.

But the environment, built or natural, would be most transformed by the experiments of a few individuals with fossil fuels. Dud Dudley, an illegitimate child of the 5th Baron Dudley, in the 1620s experimented with smelting iron with peat and coal. Dudley was not the first to do so — the patent on using coal instead of charcoal to work iron had been sold on from person to person since at least 1589 — but his experiments were among the most influential. The famous Abraham Darby, who achieved commercial success in applying coal to smelting metals in the early eighteenth century, was Dud Dudley’s great-great-nephew.

The decade also saw major new attempts to use coal as a fuel in other processes, such as glass-making. Although the patent on using coal to make glass had been around since at least 1610, by the 1620s Sir Robert Mansell had bought out the partners who owned it and was pouring a fortune into setting up glassworks at Newcastle. In this case, the transformation was institutional. Mansell’s political connections allowed him to widen the terms of his patent, such that he even tried to ban all other kinds of glass in England, regardless of whether they were made using other fuels, or even imported. Usually, patents of invention were for things entirely new, and were not supposed to interfere with existing English industries. But over the course of the 1610s, various abuses like Mansell’s came to light. King James I, eager for cash, had sold monopolies on ancient trades, as well as the new — one crony was even awarded a patent for inns and alehouses. Mansell’s patent, along with the others, was attacked in Parliament in the 1620s, and even revoked. The outcry ultimately led to the Statute of Monopolies of 1624 — the earliest patent legislation in England, which sought to regulate the royal practice of granting them. (Ironically, Mansell was so well-connected that he managed to get his controversial glass-making patent renewed and then exempted from the new Act.) The Statute of Monopolies was the only English patent legislation in force during the Industrial Revolution — there was no more patent legislation until 1852.

Finally, the ’20s saw a transformation of science. It was the decade in which Francis Bacon published some of his most significant works, on how to collect, refine, and systematise human knowledge for the good of humankind. He set out a comprehensive programme for the organisation of science and invention, with his utopian work New Atlantis setting out his ideal R&D lab – “Salomon’s House”. (Despite these high-minded aims, Bacon was also Mansell’s brother-in-law, and as attorney-general had helped draft the controversial glass-making patent. In 1621 he was convicted, fined, and even briefly imprisoned in the Tower of London for his role in the corrupt early patent system, though he appears to have been a scapegoat.)

November 4, 2019

A Tale of Swords and Gunpowder – Weapons in Ancient China l HISTORY OF CHINA

IT’S HISTORY

Published 12 Aug 2015Dao, Gun, Jian and Quiang are the four main traditional fighting weapons of China. Even though, the Chinese had already invented gunpowder by the end of the tenth century. So besides of having an arsenal of swords, spears, sabres, crossbows and bow and arrows, the Chinese military could also choose from cannons, rockets, mines and even handheld firearms. Still, close combat would remain the favoured means of battle for a long time. All about the history of Chinas weaponry now on IT’S HISTORY!

» SOURCES

Videos: British Pathé (https://www.youtube.com/user/britishp…)

Pictures: mainly Picture Alliance

Content:

Lu Gwei-Djen, Joseph Needham and Phan Chi-Hsing (1988): “The Oldest Representation of a Bombard”. In:

Technology and Culture 29 (3), pp. 594-605

Needham, Joseph (1986): Science and Civilization in China. Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic. Taipei

Tittmann, Wilfried/ Nibler, Ferdinand & John, Wolfgang ()

“Salpeter und Salpetergewinnung im Übergang vom Mittelalter zur Neuzeit”: http://www.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/technik…

Wang Ling (1947): “On the Invention and Use of Gunpowder and Firearms in China”. In: Isis 37 (3/4), 160-178» ABOUT US

IT’S HISTORY is a ride through history – Join us discovering the world’s most important eras in IN TIME, BIOGRAPHIES of the GREATEST MINDS and the most important INVENTIONS.» HOW CAN I SUPPORT YOUR CHANNEL?

You can support us by sharing our videos with your friends and spreading the word about our work.» CAN I EMBED YOUR VIDEOS ON MY WEBSITE?

Of course, you can embed our videos on your website. We are happy if you show our channel to your friends, fellow students, classmates, professors, teachers or neighbors. Or just share our videos on Facebook, Twitter, Reddit etc. Subscribe to our channel and like our videos with a thumbs up.» CAN I SHOW YOUR VIDEOS IN CLASS?

Of course! Tell your teachers or professors about our channel and our videos. We’re happy if we can contribute with our videos.» CREDITS

Presented by: Guy Kiddey

Script by: Martin Haldenmair

Directed by: Daniel Czepelczauer

Director of Photography: Markus Kretzschmar

Music: Markus Kretzschmar

Sound Design: Bojan Novic

Editing: Franz JänichA Mediakraft Networks original channel

Based on a concept by Florian Wittig and Daniel Czepelczauer

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard-Olsson, Spartacus Olsson

Head of Production: Michael Wendt

Producer: Daniel Czepelczauer

Social Media Manager: Laura Pagan and Florian WittigContains material licensed from British Pathé

All rights reserved – © Mediakraft Networks GmbH, 2015

July 20, 2019

QotD: Spices

Why do we use spices in our foods? In thinking about this question keep in mind that (1) other animals don’t spice their foods, (2) most spices contribute little or no nutrition to our diets, and (3) the active ingredients in many spices are actually aversive chemicals, which evolved to keep insects, fungi, bacteria, mammals and other unwanted critters away from the plants that produce them.

Several lines of evidence indicate that spicing may represent a class of cultural adaptations to the problem of food-borne pathogens. Many spices are antimicrobials that can kill pathogens in foods. Globally, common spices are onions, pepper, garlic, cilantro, chili peppers (capsicum) and bay leaves. Here’s the idea: the use of many spices represents a cultural adaptation to the problem of pathogens in food, especially in meat. This challenge would have been most important before refrigerators came on the scene. To examine this, two biologists, Jennifer Billing and Paul Sherman, collected 4578 recipes from traditional cookbooks from populations around the world. They found three distinct patterns.

1. Spices are, in fact, antimicrobial. The most common spices in the world are also the most effective against bacteria. Some spices are also fungicides. Combinations of spices have synergistic effects, which may explain why ingredients like “chili power” (a mix of red pepper, onion, paprika, garlic, cumin and oregano) are so important. And, ingredients like lemon and lime, which are not on their own potent anti-microbials, appear to catalyze the bacteria killing effects of other spices.

2. People in hotter climates use more spices, and more of the most effective bacteria killers. In India and Indonesia, for example, most recipes used many anti-microbial spices, including onions, garlic, capsicum and coriander. Meanwhile, in Norway, recipes use some black pepper and occasionally a bit of parsley or lemon, but that’s about it.

3. Recipes appear to use spices in ways that increase their effectiveness. Some spices, like onions and garlic, whose killing power is resistant to heating, are deployed in the cooking process. Other spices like cilantro, whose antimicrobial properties might be damaged by heating, are added fresh in recipes.

Thus, many recipes and preferences appear to be cultural adaptations adapted to local environments that operate in subtle and nuanced ways not understood by those of us who love spicy foods. Billing and Sherman speculate that these evolved culturally, as healthier, more fertile and more successful families were preferentially imitated by less successful ones. This is quite plausible given what we know about our species’ evolved psychology for cultural learning, including specifically cultural learning about foods and plants.

Among spices, chili peppers are an ideal case. Chili peppers were the primary spice of New World cuisines, prior to the arrival of Europeans, and are now routinely consumed by about a quarter of all adults, globally. Chili peppers have evolved chemical defenses, based on capsaicin, that make them aversive to mammals and rodents but desirable to birds. In mammals, capsicum directly activates a pain channel (TrpV1), which creates a burning sensation in response to various specific stimuli, including acid, high temperatures and allyl isothiocyanate (which is found in mustard or wasabi). These chemical weapons aid chili pepper plants in their survival and reproduction, as birds provide a better dispersal system for the plants’ seeds than other options (like mammals). Consequently, chilies are innately aversive to non-human primates, babies and many human adults. Capsaicin is so innately aversive that nursing mothers are advised to avoid chili peppers, lest their infants reject their breast (milk), and some societies even put capsicum on mom’s breasts to initiate weaning. Yet, adults who live in hot climates regularly incorporate chilies into their recipes. And, those who grow up among people who enjoy eating chili peppers not only eat chilies but love eating them. How do we come to like the experience of burning and sweating — the activation of pain channel TrpV1?

Research by psychologist Paul Rozin shows that people come to enjoy the experience of eating chili peppers mostly by re-interpreting the pain signals caused by capsicum as pleasure or excitement. Based on work in the highlands of Mexico, children acquire this gradually without being pressured or compelled. They want to learn to like chili peppers, to be like those they admire. This fits with what we’ve already seen: children readily acquire food preferences from older peers. In Chapter 14, we further examine how cultural learning can alter our bodies’ physiological response to pain, and specifically to electric shocks. The bottom line is that culture can overpower our innate mammalian aversions, when necessary and without us knowing it.

Joseph Henrich, The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter, 2015.

June 18, 2019

Blitzkrieg on Speed – Nazis on Crystal Meth Part 2 – WW2 SPECIAL

World War Two

Published on 17 Jun 2019While many armies use performance enhancing drugs during WW2, the Wehrmacht takes it to extremes in 1940, with more than debatable consequences.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvJoin our Discord Server: https://discord.gg/D6D2aYN.

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesHosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Astrid Deinhard, Joram Appel and Spartacus Olsson

Produced and Directed by: Spartacus Olsson and Astrid Deinhard

Executive Producers: Bodo Rittenauer, Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Joram Appel and Astrid Deinhard

Edited by: Spartacus Olsson

Sound Engineering: Joakim BrodénColorisations by Spartacus Olsson

Archive by Reuters/Screenocean http://www.screenocean.com

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

World War Two

1 hour ago

Read before you comment; “it wasn’t just the Germans” This video treats the use of methamphetamine by the German Wehrmacht and its cultural background. The purpose of this video is not to attribute any atrocities that the Nazis perpetrated to that they were simply on drugs – we know that this was not a contributing factor to what they did, although it perhaps influenced how they did it. It is also not the purpose of this video to single out Germany as the only belligerent to use drugs in WW2. As we point out in the video, many belligerents (to not say all) used drugs, especially amphetamines during WW2. In fact amphetamines are still in official, monitored used by for instance the US Army in some situations to this day. However, the Wehrmacht and a few of the Axis allies used methamphetamine which is different than amphetamine as the effects of meth is unpredictable and comes on faster and harder. These unpredictable effects include hallucinations and delusions, which amphetamines do not induce, or at least to a lesser and more predictable degree. Methamphetamine metabolizes into amphetamine in the body, but in that process it creates a number of side effects that contribute to its unstable effects. Of course this was poorly understood in 1940 and meth was also available commercially over the counter in many places like the US and Australia, mostly as a dieting pill and (somewhat ironically) an anti-depressant. While amphetamines like Benzedrine are still administered by doctors for certain conditions, methamphetamine is now known to be a very dangerous, potentially lethal, drug that only has recreational use, and in 2019 it is therefore illegal almost everywhere in the world. Last but not least, the Wehrmacht was singular in how liberal they were in distributing drugs to the troops, at least to begin with. It is important to also point out that beside the official use of drugs, many soldiers throughout the ages have resorted to intoxicating themselves to deal with the unfathomable horrors of war, and in this respect WW2 was no different. We will cover drug use by other belligerents and in general during the war in future videos.

May 7, 2019

The Science of Ginger: Why and How it Burns and Its Impact on Cooking | Ginger | What’s Eating Dan?

America’s Test Kitchen

Premiered on 22 Mar 2019Why does ginger burn? Why does ginger turn pink? How come ginger makes meat mushy? Dan answers these questions and more about one of the most interesting ingredients cooks have at their disposal in this episode of What’s Eating Dan?.

Click here to browse our ginger recipes: https://cooks.io/2FlixBy

Click here for our Ginger Snap recipe: https://cooks.io/2JuniOB

Click here for our Ginger-Scallion Everything Sauce recipe: https://cooks.io/2Yh01Tu

How to make Ginger-Milk Curd and the science behind it: https://blog.khymos.org/2014/02/24/gi…ABOUT US: Located in Boston’s Seaport District in the historic Innovation and Design Building, America’s Test Kitchen features 15,000 square feet of kitchen space including multiple photography and video studios. It is the home of Cook’s Illustrated magazine and Cook’s Country magazine and is the workday destination for more than 60 test cooks, editors, and cookware specialists. Our mission is to test recipes over and over again until we understand how and why they work and until we arrive at the best version.

April 22, 2019

QotD: Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier

It was surprising how much I did not know about Lavoisier; and of how little importance it was. He is Saint George killing the dragon of Phlogiston in this account. Father of modern chemistry, &c. Student of heat and respiration; improver of gunpowder; hyper-efficient tax collector in the bureaucracy of the French Old Regime; academician; weekend geologist; dreamer in agriculture and economics; aristocratic gardener whose works around his Château de Frechines might plausibly be described as an experimental farm; social climber and assiduous self-promoter, whose fame could not hide him from the glinting blades of Robespierre.

A very clever man was our Lavoisier, the more charming the farther one got away from him (often I read between the lines); whose pleasure, once he took offices in the Arsenal at Paris, with a budget to do largely as he pleased, was to conduct violent experiments on anything that was lying around. His revolution in chemistry consisted of quantifying it all.

When a child, I had the evil of Phlogiston brought to my attention. It was, not from the Dark Ages as popularly supposed, but only from the end of the seventeenth century, the prevailing “settled science” on the combustible principle in the air, and other substances. It was pure theory, and surprisingly easy to kick over with a few methodical tests; notwithstanding the scientific establishment of the day kicked, screamed, and desperately resisted every attempt to displace it. Lavoisier (and Priestley in England) burnt or blew up one thing and another until Lavoisier had discovered and named Oxygen.

And so we advanced from Phlogiston to Oxygen, and incidentally to ascending in hot air balloons. Good show!

David Warren, “Phlogiston”, Essays in Idleness, 2016-05-31.

April 13, 2019

April 5, 2019

QotD: Debunking the “MSG is harmful” myth

The story of MSG is a true tragedy. The negativity associated with this delicious amino acid is due to a spurious study from 1968 that linked MSG with the “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.” This study connected that gut-bomb feeling you sometimes get after eating Chinese food to MSG, despite the fact that the typically cheap Chinese food prepared in American restaurants is fatty and served in large portions, and (like any restaurant), the food can be spoiled. My mom theorizes that lots of MSG was used to cover up the fact that, say, shrimp was a day past its prime, and that the sick feeling was due to the food but got blamed on the MSG. There’s never been a scientifically rigorous study that’s linked MSG with any negative effects. MSG should be used frequently and added to anything that needs the flavor drawn out, especially soups. But it enhances virtually anything it touches: Once, eating pizza at home, a friend scanned my spice rack and saw a jar with white powder whose label, in my grandfather’s messy scrawl, read what looked like “MS6.” He sprinkled it on his pizza and came to find me, telling me that whatever MS6 was, it was the most amazing thing he’d ever tasted. Yes, MSG makes even pizza better.

Caitlin PenzeyMoog, “Salt grinders are bullshit, and other lessons from growing up in the spice trade”, The A.V. Club, 2017-04-06.

March 1, 2019

Theodore Dalrymple on Michel Houellebecq: “Houellebecq runs an abattoir for sacred cows”

At the New English Review:

Not reading many contemporary French novels, I am not entitled to say that Michel Houellebecq is the most interesting French novelist writing today, but he is certainly very brilliant, if in a somewhat limited way. His beam is narrow but very penetrating, like that of a laser, and his theme an important, indeed a vital one: namely the vacuity of modern life in the West, its lack of transcendence, lived as it is increasingly without religious or political belief, without a worthwhile creative culture, often without deep personal attachments, and without even a struggle for survival. Into what Salman Rushdie (a much lesser writer than Houellebecq) called “a God-shaped hole” has rushed the search for sensual pleasure which, however, no more than distracts for a short while.

Something more is needed, but Western man — at least Western man at a certain level of education, intelligence and material ease — has not found it. Houellebecq’s underlying nihilism implies that it is not there to be found. The result of this lack of transcendent purpose is self-destruction not merely on a personal, but on a population, scale. Technical sophistication has been accompanied, or so it often seems, by mass incompetence in the art of living. Houellebecq is the prophet, the chronicler, of this incompetence.Even the ironic title of his latest novel, Sérotonine, is testimony to the brilliance of his diagnostic powers and his capacity to capture in a single word the civilizational malaise which is his unique subject. Serotonin, as by now every self-obsessed member of the middle classes must know, is a chemical in the brain that acts as a neurotransmitter to which is ascribed powers formerly ascribed to the Holy Ghost. All forms of undesired conduct or feeling are caused by a deficit or surplus or malalignment of this chemical, so that in essence all human problems become ones of neurochemistry.

On this view, unhappiness is a technical problem for the doctor to solve rather than a cause for reflection and perhaps even for adjustment to the way one lives. I don’t know whether in France the word malheureux has been almost completely replaced by the word déprimée, but in English unhappy has almost been replaced by depressed. In my last years of medical practice, I must have encountered hundreds, perhaps thousands, of depressed people, or those who called themselves such, but the only unhappy person I met was a prisoner who wanted to be moved to another prison, no doubt for reasons of safety.

Houellebecq’s one-word title captures this phenomenon (a semantic shift as a handmaiden to medicalisation) with a concision rarely equalled. And indeed, he has remarkably sensitive antennae to the zeitgeist in general, though it must be admitted that he is most sensitive to those aspects of it that are absurd, unpleasant, or dispiriting rather than to any that are positive.

February 25, 2019

QotD: Defining mineral reserves

The European chemists organisation – EuChemS – has just added to the torrent of environmental drivel with their new periodic table. They’re trying to tell us which elements are going to run out when and thus tell us all that we’ve got to recycle. The entire process is bunkum because they’ve not understood the first thing about the supply of minerals. They simply do not know the meaning of mineral reserve that is.

Just for the edification of anyone who does drool when contemplating their own nasal effluvia – you know, a member of Greenpeace, that sort of person – a mineral reserve is something we’ve proven, yes proven, that we can extract from using today’s technology, at today’s prices, and make a profit. It costs a lot of money to prove these facts. Thus we only prove for what we’re likely to use in the next few decades. Mineral reserves are, to a reasonable level of accuracy, just the working stock of current mines.

There is no relationship, no relationship at all, between our mineral reserves and how much of that element or mineral is available to us to use. Really do grasp this point. It’s not that the amount is larger. It’s not that the multiple is high. It’s that there is no relationship at all. There are, for example, absolutely no mineral reserves of hafnium anywhere on the planet. Nothing, absolutely nada. At current rates of usage we might run out some few billion years after the Sun goes Red Giant. The European Chemical Society tries to tell us that there’s a serious risk of running short of Hafnium in the next 100 years. This is so gibberingly stupid that it would get a laugh from German geologists – I know because I told some this once and they giggled. Seriously, German – German – geologists, giggling.

Tim Worstall, “More Environmental Drivel With New Periodic Table – We’re Going To Run Out Of Helium”, Continental Telegraph, 2019-01-23.

October 28, 2018

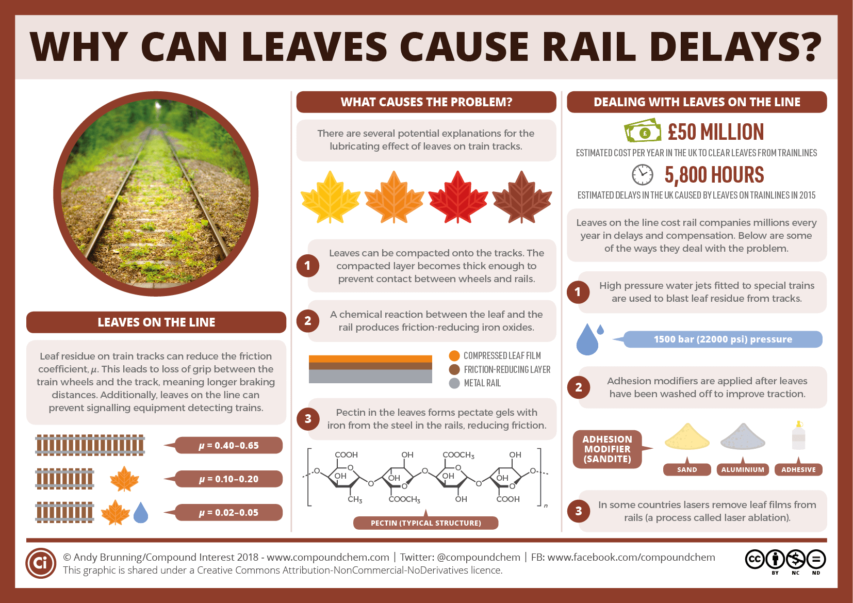

The actual science behind the “leaves on the line” excuse for late trains

While it doesn’t explain the “wrong type of snow” excuse also deployed by announcers when Britain’s trains run inexplicably slow in winter, here’s the scientific facts about the “leaves on the line” excuse:

Autumn is here, and for most of us, it’s a time of beauty as the leaves cascade through an array of hues before pirouetting down from the trees. If you have to travel by train, however, you might tire of ‘leaves on the line’ being the supposed cause of train delays. It turns out to be more than just a flimsy excuse – and particular chemical reactions are partly to blame.

We’ve previously looked at the chemical cause of the colours of autumn leaves. By the time they make their descent from trees to the ground, most of these colours have passed. What remains is a brown husk, mainly made up of cellulose. Cellulose is the biological polymer that is the main component of plant cell walls.

Once leaves have fallen from trees, they simply decompose over time. Their presence isn’t usually a problem until it comes to the train network. When leaves fall on train lines, they can reduce the grip between the train wheels and the track. This, in turn, can lead to longer braking distances for trains. By disrupting the contact between the train wheels and the track, the leaves also prevent signalling equipment detecting trains. This can then cause train delays.

What makes leaves affect train tracks in this way? Scientists have a few suggestions, and it’s likely that they all contribute to the problem to some extent.

May 29, 2018

“[T]here’s just no way that we’re going to get to fentanyl harm reduction without [legalization]”

Tim Worstall reports on a recent Nebraska drug bust involving enough fentanyl “to kill 26 million people” (that is, about 120 lbs of the stuff) and explains why the current enforcement regime is going to have to change:

Now, I’m in favour of all of these drugs being legalised anyway. It’s the idiot’s body, up to them what they ingest in whatever manner. If it kills them, well, their choice. The argument that they shouldn’t therefore we must prevent them doesn’t cut much ice with me.

But put that aside and think in a utilitarian manner. If we can prevent overdoses and wasted lives then we should. But only if how we’re going to do it is better than the results of either not doing so or even using some other manner of dealing with the problem.

It’s arguable that clamping down on certain illegal drugs does at least limit their penetration of the market. I don’t think this is true of heroin but perhaps it is potentially true. It’s absolutely not true of fentanyl. For that’s a synthetic opioid. A decent chemist can synthesise it – a good one can make the precursors as well. There is no need to get opium, morphine or any other poppy related product that we already control.

It’s also, as we can see, alarmingly cheap already. Easy to smuggle in vast quantities of doses.

There’s another problem with it. The difference between a dose that gives a high and one that kills is pretty narrow. And it’s an extremely potent drug as well. Quantities for either are small – smaller than can generally be measured by users with candles and teaspoons.

It’s cheap, easy enough to make, has no precursors we can control, kills easily enough and dosage is alarmingly difficult to get right. So, what do we do?

We’re not going to get rid of it for all of the above reasons. So, we need to do damage limitation. Stopping people from dying from it sounds like a pretty good idea actually. And that means that we need it to be pure and in known dosages. That is, we need it to be legal.

I think all drugs should be legal, hey, your body and all that. But even if you think that harm reduction is a more important goal there’s just no way that we’re going to get to fentanyl harm reduction without legality of it. For that’s the only way we will get it in known doses which don’t kill people. And we’re most assuredly going to keep getting it even if we don’t legalise it. Our choices are people tooting on illegal fentanyl and dying or people tooting on legal fentayl and not dying. Not such a toughie that question, is it?

May 9, 2018

What Makes Spicy Foods Spicy | Earth Lab

BBC Earth Lab

Published on 24 Aug 2017Greg Foot explains why some food is spicy!