Finally, it is 1928. Hoover feels like he has accomplished his goal of becoming the sort of knowledgeable political insider who can run for President successfully. Calvin Coolidge decides not to run for a second term (in typical Coolidge style, he hands a piece of paper to a reporter saying “I do not choose to run for President in 1928” and then disappears and refuses to answer further questions). The Democrats nominate Al Smith, an Irish-Italian Catholic with a funny accent; it’s too early for the country to really be ready for this. Historians still debate whether Hoover and/or his campaign deserves blame for being racist or credit for being surprisingly non-racist-under-the-circumstances.

The main issue is Prohibition. Smith, true to his roots, is against. Hoover, true to his own roots (his mother was a temperance activist) is in favor. The country is starting to realize Prohibition isn’t going too well, but they’re not ready to abandon it entirely, and Hoover promises to close loopholes and fix it up. Advantage: Hoover.

The second issue is tariffs. Everyone wants some. Hoover promises that if he wins, he will call a special session of Congress to debate the tariff question. Advantage: Hoover.

The last issue is personality. Republican strategists decide the best way for their candidate to handle his respective strengths and weaknesses is not to campaign at all, or be anywhere near the public, or expose himself to the public in any way. Instead, they are “selling a conception. Hoover was the omnicompetent engineer, humanitarian, and public servant, the ‘most useful American citizen now alive’. He was an almost supernatural figure, whose wisdom encompasses all branches, whose judgment was never at fault, who knew the answers to all questions.” Al Smith is supremely charismatic, but “boasted of never having read a book”. Advantage: unclear, but Hoover’s strategy does seem to work pretty well for him. He racks up most of the media endorsements. Only TIME Magazine dissents, saying that “In a society of temperate, industrious, unspectacular beavers, such a beaver-man would make an ideal King-beaver. But humans are different.”

Apparently not that different. Hoover wins 444 votes to 87, one of the greatest electoral landslides in American history.

Anne McCormick of the New York Times describes the inauguration:

We were in a mood for magic … and the whole country was a vast, expectant gallery, its eyes focused on Washington. We had summoned a great engineer to solve our problems for us; now we sat back comfortable and confidently to watch our problems being solved. The modern technical mind was for the first time at the head of a government. Relieved and gratified, we turned over to that mind all of the complications and difficulties no other had been able to settle. Almost with the air of giving genius its chance, we waited for the performance to begin.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

March 11, 2025

QotD: Herbert Hoover wins the presidency

December 7, 2024

Rediscovering the legacy of “Silent Cal”

Jacob M. Farley recently discovered the history of Calvin Coolidge’s presidency and the economic policies he pursued to such good effect in the 1920s (although Herbert Hoover’s energetic turn as Commerce Secretary for Harding and Coolidge strongly indicated that the benign laissez faire approach would be changed once Coolidge left the Oval Office):

Calvin Coolidge, Governor of Massachusetts, 1919.

Photo by Notman Studio, Boston, restored by Adam Cuerden via Wikimedia Commons.

In the pantheon of American presidents, Calvin Coolidge, or “Silent Cal”, often plays the role of the overlooked extra in the corner of history’s grand narrative. I can attest to this, as my first real exposure to him occurred recently during a visit to a museum whilst travelling in the US. Having spent some time since then reading up on everything Cal-related, I’ve become increasingly convinced that there’s a compelling case to be made that Coolidge’s approach to governance, particularly his economic policies, should be dusted off and revisited, not just for historical curiosity but as a lodestar for free marketeers far and wide.

Before I go any further, let’s set the scene of Coolidge’s era. The 1920s is often remembered for jazz, flappers, and the stock market’s dizzying heights. But beneath the cultural tumult, Coolidge was busy orchestrating what can quite fairly be called a symphony of minimalistic governance. His philosophy was profoundly simple: government should do less, not more.

Whilst this may seem extraordinarily mundane to you, consider that this wasn’t simply cheap talk on the campaign trail designed to get a nod of approval from over-50s. His ideas weren’t born out of laziness or disinterest but from a profound belief in the efficacy of the market’s invisible hand over the visible, often clumsy, hand of government intervention.

Coolidge’s administration slashed taxes like a bootlegger cuts whiskey – to make the good times flow more freely, notably through the Revenue Acts of 1924 and 1926. This wasn’t just about giving the rich a break; it was about stimulating economic activity by leaving more money in the pockets of Americans. By leaving more money in the pockets of Americans, he was essentially saying, “Here’s your allowance, now go make some noise at the stock market”.

The result? A crescendo of consumer spending, industrial growth, and a stock market that seemed to reach for the stars.

Coolidge believed in setting the rules of the game and then letting the players play. This isn’t to say there was no regulation, but rather, it was about not over-regulating, about allowing businesses to innovate, expand, and yes, even fail, without the government always having its finger on the scale. Imagine if the conductor only pointed out the tempo and let the musicians interpret it – that was Coolidge’s regulatory approach.

Under Coolidge, the U.S. economy boomed. Unemployment dipped to levels we can only dream of today, and real GDP growth was robust. If the economy were a piece of music, it was hitting all the right notes. But here’s where the narrative often shifts to a sombre tone – the Great Depression. While Coolidge left office before the market crashed, the seeds of economic disaster were arguably sown in the very success of the 1920s, exacerbated by policies that followed his term, particularly those of the Federal Reserve.

This is where the story of Coolidge’s economic policy gets nuanced. The Federal Reserve, relatively new on the scene, played its own tune by the late 1920s. Its policies, intended to stabilise the economy, are often critiqued for contributing to the eventual bust. Coolidge’s hands-off approach might have been a wise nod to market self-correction, but the Fed’s actions, flooding the number of dollars in circulation to stimulate the market’s trajectory in a way they deemed desirable, led to an artificially manufactured drunkenness, leading to a nasty hangover – The Great Depression.

After Coolidge, the economy didn’t just crash; it was like the Charleston dancer tripped over its own feet.

There had been a brief, nasty recession following the end of the First World War, but Harding and Coolidge responded not by muscular government action but by letting the market sort things out. Hoover, as Coolidge’s successor, was not cut from that cloth. Hoover was a believer in the progressive big-government approach to just about everything and his attempts to respond after the 1929 crash absolutely made things much, much worse. Later historians have chosen to forget Hoover’s actual policies and pretend that he followed Coolidge’s lead (most historians over the next couple of generations were pro-Roosevelt, so portraying Hoover as a conservative non-interventionist allowed them to contrast that with Roosevelt’s even more centralizing, interventionist policies).

December 6, 2024

QotD: Herbert Hoover in the Harding and Coolidge years

[Herbert] Hoover wants to be president. It fits his self-image as a benevolent engineer-king destined to save the populace from the vagaries of politics. The people want Hoover to be president; he’s a super-double-war-hero during a time when most other leaders have embarrassed themselves. Even politicians are up for Hoover being president; Woodrow Wilson has just died, leaving both Democrats and Republicans leaderless. The situation seems perfect.

Hoover bungles it. He plays hard-to-get by pretending he doesn’t want the Presidency, but potential supporters interpret this as him just literally not wanting the Presidency. He refuses to identify as either a Democrat or Republican, intending to make a gesture of above-the-fray non-partisanship, but this prevents either party from rallying around him. Also, he might be the worst public speaker in the history of politics.

Warren D. Harding, a nondescript Senator from Ohio, wins the Republican nomination and the Presidency. Hoover follows his usual strategy of playing hard-to-get by proclaiming he doesn’t want any Cabinet positions. This time it works, but not well: Harding offers him Secretary of Commerce, widely considered a powerless “dud” position. Hoover accepts.

Harding is famous for promising “return to normalcy”, in particular a winding down of the massive expansion of government that marked WWI and the Wilson Administration. Hoover had a better idea – use the newly-muscular government to centralize and rationalize American In his first few years in Commerce – hitherto a meaningless portfolio for people who wanted to say vaguely pro-prosperity things and then go off and play golf – Hoover instituted/invented housing standards, traffic safety standards, industrial standards, zoning standards, standardized electrical sockets, standardized screws, standardized bricks, standardized boards, and standardized hundreds of other things. He founded the FAA to standardize air traffic, and the FCC to standardize communications. In order to learn how his standards were affecting the economy, he founded the NBER to standardize government statistics.

But that isn’t enough! He mediates a conflict between states over water rights to the Colorado River, even though that would normally be a Department of the Interior job. He solves railroad strikes, over the protests of the Department of Labor. “Much to the annoyance of the State Department, Hoover fielded his own foreign service.” He proposes to transfer 16 agencies from other Cabinet departments to the Department of Commerce, and when other Secretaries shot him down, he does all their jobs anyway. The press dub him “Secretary of Commerce and Undersecretary Of Everything Else”.

Hoover’s greatest political test comes when the market crashes in the Panic of 1921. The federal government has previously ignored these financial panics. Pre-Wilson, it was small and limited to its constitutional duties – plus nobody knows how to solve a financial panic anyway. Hoover jumps into action, calling a conference of top economists and moving forward large spending projects. More important, he is one of the first government officials to realize that financial panics have a psychological aspect, so he immediately puts out lots of press releases saying that economists agree everything is fine and the panic is definitely over. He takes the opportunity to write letters saying that Herbert Hoover has solved the financial panic and is a great guy, then sign President Harding’s name to them. Whether or not Hoover deserves credit, the panic is short and mild, and his reputation grows.

While everyone else obsesses over his recession-busting, Hoover’s own pet project is saving the Soviet Union. Several years of civil war, communism, and crop failure have produced mass famine. Most of the world refuses to help, angry that the USSR is refusing to pay Czarist Russia’s debts and also pretty peeved over the whole Communism thing. Hoover finds $20 million to spend on food aid for Russia, over everyone else’s objection […]

So passed the early 1920s. Warren Harding died of a stroke, and was succeeded by Vice-President “Silent Cal” Coolidge, a man famous for having no opinions and never talking. Coolidge won re-election easily in 1924. Hoover continued shepherding the economy (average incomes will rise 30% over his eight years in Commerce), but also works on promoting Hooverism, his political philosophy. It has grown from just “benevolent engineers oversee everything” to something kind of like a precursor modern neoliberalism:

Hoover’s plan amounted to a complete refit of America’s single gigantic plant, and a radical shift in Washington’s economic priorities. Newsmen were fascinated by is talk of a “third alternative” between “the unrestrained capitalism of Adam Smith” and the new strain of socialism rooting in Europe. Laissez-faire was finished, Hoover declared, pointing to antitrust laws and the growth of public utilities as evidence. Socialism, on the other hand, was a dead end, providing no stimulus to individual initiative, the engine of progress. The new Commerce Department was seeking what one reporter summarized as a balance between fairly intelligent business and intelligently fair government. If that were achieved, said Hoover, “we should have given a priceless gift to the twentieth century.”

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

August 2, 2023

QotD: The Coolidge years

I washed my car this morning and it rained this afternoon. Therefore, washing cars causes rain.

So-called “progressives” tell us that Calvin Coolidge was a bad president because the Great Depression started just months after he left office.

This is precisely the same, lame argument expressed in two different contexts.

In five years (August 2023), we will mark the 100th anniversary of the day that Silent Cal became America’s 30th President. I intend to celebrate it along with others who believe in small government, but you can bet there’ll be plenty of progressives trying to rain on our parade. So let’s get those umbrellas ready.

Let’s remember that the eight years of Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921) were economically disastrous. Taxes soared, the dollar plummeted, and the economy soured. A sharp, corrective recession in 1921 ended quickly because the new Harding-Coolidge administration responded to it by reducing the burden of government. When Harding died suddenly in 1923, Coolidge became President and for the next six years, America enjoyed the unprecedented growth of “the Roaring ’20s.” Historian Burton Folsom elaborates:

One measure of prosperity is the misery index, which combines unemployment and inflation. During Coolidge’s six years as president, his misery index was 4.3 percent — the lowest of any president during the twentieth century. Unemployment, which had stood at 11.7 percent in 1921, was slashed to 3.3 percent from 1923 to 1929. What’s more, [Coolidge’s Treasury Secretary] Andrew Mellon was correct on the effects of the tax-rate cuts — revenue from income taxes steadily increased from $719 million in 1921 to over $1 billion by 1929. Finally, the United States had budget surpluses every year of Coolidge’s presidency, which cut about one-fourth of the national debt.

That’s a record “progressives” can only dream about but never deliver. Yet when they rank U.S. presidents, Coolidge gets the shaft. If you can get your hands on a copy of the out-of-print 1983 book, Coolidge and the Historians by Thomas Silver, buy it! You’ll be delighted at what Coolidge actually said, and simultaneously incensed at the shameless distortions of his words at the hands of progressives like Arthur Schlesinger.

Lawrence W. Reed, “Cal and the Big Cal-Amity”, Foundation for Economic Education, 2018-07-25.

November 19, 2022

American political parties from 1865 down to the Crazy Years we’re living through now

Severian responds to a comment about the Democrats and Republicans and how they have morphed over the years to the point neither party would recognize itself:

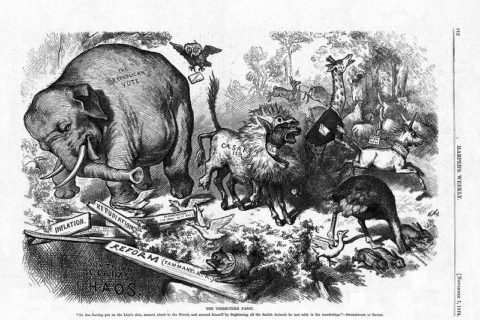

“The Third-Term Panic”, by Thomas Nast, originally published in Harper’s Magazine on 7 November 1874.

A braying ass, in a lion’s coat, and “N.Y. Herald” collar, frightening animals in the forest: a giraffe (“N. Y. Tribune”), a unicorn (“N. Y. Times”), and an owl (“N. Y. World”); an ostrich, its head buried, represents “Temperance”. An elephant, “The Republican Vote”, stands near broken planks (Inflation, Repudiation, Home Rule, and Re-construction). Under the elephant, a pit labeled “Southern Claims. Chaos. Rum.” A fox (“Democratic Party”) has its forepaws on the plank “Reform. (Tammany. K.K.)” The title refers to U.S. Grant’s possible bid for a third presidential term. This possibility was criticized by New York Herald owner and editor James Gordon Bennett, Jr.

Image and caption via Wikimedia Commons.

I find this extremely useful. I’d add that the postbellum parties do shift ideologies fairly regularly, as PR notes, such that even though they’re still called by the same names, they’re nowhere near the same parties, 1865-present.

I’d add some distinguishing tags for ease of reference, like so:DEMOCRATS:

The Redeemers of the “Solid South”, 1865-1882, when their main issue was ending Reconstruction and establishing Jim Crow.

The Grover Cleveland years, 1882-1896: Still primarily an opposition party, their main goal was reining in the ridiculous excesses of the Gilded Age Republicans. As one of about 100 people worldwide who have strong opinions on Grover Cleveland, I should probably recuse myself here, so let me just say this: Union Army veterans were to the Gilded Age GOP what the Ukraine is to the Uniparty now. They simply couldn’t shovel money at them fast enough, and the guys who orchestrate those ridiculous flag-sucking “thank you for your service” celebrations before pro sporting events would tell them to tone it way, way down. Cleveland spent most of his presidency slapping the worst of this down.

[How bad was it? So bad that not only did they pass ridiculous giveaways like the Arrears of Pension Act and the Dependent Pension Act — think “Build Back Brandon” on steroids, times two, plus a bunch of lesser boondoggles — but they got together every Friday night when Congress was in session to pass “private” pension bills. These are exactly what they sound like: Federal pensions to one specific individual, put up by his Congressman. Grover Cleveland used to burn the midnight oil vetoing these ridiculous fucking things, which makes him a true American hero as far as I’m concerned].

The Populist Party years, 1896-1912: They were more or less absorbed by the Populist Party — William Jennings Bryan ran as a “Democrat” in 1896, but he was really a Populist; that election hinged entirely on economic issues. They still had the “Solid South”, but the Democrats of those years were basically Grangers.

The Progressive Years, 1912-1968: They picked up all the disaffected “Bull Moose” Republicans who split the ticket and handed the Presidency to Woodrow Wilson in 1912, becoming the pretty much openly Fascist entity they’d remain until 1968.

The Radical Party, 1968-1992: The fight between the Old and New Left, or Marxism vs. Maoism.

The Boomer Triumphalist Party, 1992-2000. It’s an Alanis-level irony that Bill Clinton was the most “conservative” president in my lifetime, if the metric for “conservatism” is “what self-proclaimed conservatives say they want”. This was our Holiday From History, in which “wonks” reigned supreme, tweaking the commas in the tax code while occasionally making some noises about silly lifestyle shit.

The Batshit Insane Party, 2000-Present. The years of the Great Inversion. Today’s Democrats only know one thing: Whatever is, is wrong.

REPUBLICANS:

The Radical Party, 1864-1876: Determined to impose utopia at bayonet point in the conquered South, they started asking themselves why they couldn’t simply impose utopia at bayonet point everywhere. They never did figure it out, and we owe those awful, awful racists in the Democratic Party our undying thanks for that. This is the closest America ever came to a theocracy until The Current Year. Morphed into

The party of flabbergastingly ludicrous robber baron excess, 1876-1896. In these years, J.P. Morgan personally bailed out the United States Treasury. Think about that. FTX, meet Credit Mobilier. You guys are pikers, and note that was 1872. William McKinley deserves a lot more credit than he gets in pretty much everything, but he might’ve been the most fiscally sane American president. Only Calvin Coolidge is even in the ballpark.

The Progressive Party, 1900-1912. For all the Left loves to call Republicans “fascists”, for a time they were … or close enough, Fascism not being invented quite yet. But the Democrats coopted it under Wilson, leading to

The Party of (Relative) Sanity, 1912-1968. Before Warren G. and Nate Dogg, there were Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge, the only two contestants in the “American politicians with their heads screwed on straight” competition, 20th century division. Alas, superseded by the

Anti-Left Party, 1968-2000. Want to punch a hippie? Vote for Richard Nixon. Or Gerald Ford. Or, yes, the Gipper.

The Invade-the-World, Invite-the-World Branch of the Uniparty, 2000-Present. Wouldn’t it be nice if Bill Clinton could keep it in his pants, and wasn’t a walking toothache like Al Gore? That was the essence of W’s pitch in 2000. Our Holiday From History was supposed to continue, but alas, 9/11. Some very special people at the State Department got their chance to finally settle their centuries-long grudge with the Cossacks, and, well … here we are.

By my count, the longest periods of ideological consistency ran about 50 years … and I’m not sure if that really tells us much, because it makes sense to view 1914-1945, if not 1914-1991, as THE World War, which put some serious constraints on the ideology of both sides.

Trend-wise, what I see is one side going nuts with some huge moral crusade, while the other side frantically tries to slam on the brakes (while getting their beaks good and wet, of course). Antebellum, it was the proslavery side leading the charge, but if they’d been slightly less excitable in the late 1840s, the abolitionist lunatics would’ve done the job for them by the late 1860s. If you know anything about the Gilded Age, you know that they somehow presented the truly ridiculous excesses of the Robber Barons as some kind of moral triumph; this was, after all, Horatio Alger‘s America. Progressivism, of either the Marxist or the John Dewey variety, is just moralizing gussied with The Science™, and so forth.

The big difference between then and now, of course, is that the grand moral crusade of The Current Year is open, shit-flinging nihilism. The “opposition”, such as it is, is also full of shit-flinging nihilists; they just don’t want to go before they’ve squeezed every possible penny out of the Suicide of the West. So … yeah. We’re overdue for a big ideological change. And we shall get it, never fear; we can only hope that we won’t have to see it by the light of radioactive fires.

April 12, 2022

Calvin Coolidge: The Silent President

Biographics

Published 27 Sep 2021Simon’s Social Media:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/SimonWhistler

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/simonwhistler/This video is #sponsored by Squarespace.

Source/Further reading:

Miller Center, in-depth overview: https://millercenter.org/president/co…

History Today, overview: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/…

New Yorker, “The case for Coolidge” (cached): https://webcache.googleusercontent.co…

NY Times, “Coolidge, the great refrainer”: https://www.nytimes.com/2013/02/17/bo…

NY Times, 1933 obituary for Coolidge: https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytim…

Atlantic, “Coolidge and depression”: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/…

Politico, “How Coolidge survived the Harding-era scandals”: https://www.politico.com/magazine/sto…

History, “Boston Police Strike of 1919”: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-h…

Coolidge letter written after death of his son: https://www.shapell.org/manuscript/pr…

May 11, 2019

QotD: The Coolidge Effect

Behavioral endocrinologist Frank A. Beach first mentioned the term “Coolidge effect” in publication in 1955, crediting one of his students with suggesting the term at a psychology conference. He attributed the neologism to:

… an old joke about Calvin Coolidge when he was President … The President and Mrs. Coolidge were being shown [separately] around an experimental government farm. When [Mrs. Coolidge] came to the chicken yard she noticed that a rooster was mating very frequently. She asked the attendant how often that happened and was told, “Dozens of times each day.” Mrs. Coolidge said, “Tell that to the President when he comes by.” Upon being told, the President asked, “Same hen every time?” The reply was, “Oh, no, Mr. President, a different hen every time.” President: “Tell that to Mrs. Coolidge.”

The joke appears in a 1978 book (A New Look at Love, by Elaine Hatfield and G. William Walster, p. 75), citing an earlier source (footnote 19, Chapter 5).

November 25, 2018

QotD: Calvin Coolidge, master of inactivity

When asked to summarize the record of his administration, Coolidge replied, “Perhaps one of the most important accomplishments of my administration has been minding my own business.” The point wasn’t that he was lazy, the point was that it takes work to stop government from doing stupid things. “It is much more important to kill bad bills than to pass good ones,” he once remarked.

When Coolidge said, “When you see ten problems rolling down the road, if you don’t do anything, nine of them will roll into a ditch before they get to you.” Again, the point wasn’t laziness, it was confidence in the ability of society — a.k.a. the people — to figure things out for themselves. For every ten big problems our society faces, nine of them aren’t the government’s problem. Liberals think not only that all ten are the government’s problem, but that ten is an insanely low tally of the big problems the government is supposed to be dealing with. And fewer and fewer conservatives would endorse the Coolidge Ratio.

I’m increasingly convinced we’ll never have another one like him. My point isn’t that we don’t produce people like Coolidge anymore — though that’s more than a little true, too. It’s not that a Coolidge couldn’t get elected today either, though who could argue with that? It’s that even if we somehow produced a Coolidge and got him or her elected, the nature of the state is such that even Coolidge couldn’t really be Coolidge.

Jonah Goldberg, “The Unwisdom of Crowds”, National Review, 2017-01-21.

September 28, 2018

The staunch Progressive dismissal of Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge

In Richard Epstein’s review of Jill Lepore’s recent book These Truths: A History of the United States, there’s some interesting discussion of the Harding and Coolidge administrations:

Lepore’s narrative of this period begins with President Warren Harding, who, she writes, “in one of the worst inaugural addresses ever delivered,” argued, in his own words, “for lightened tax burdens, for sound commercial practices, for adequate credit facilities, for sympathetic concern for all agricultural problems, for the omission of unnecessary interference of Government with business, for an end to Government’s experiment in business, for more efficient business in Government, and for more efficient business in Government administration.” Harding’s sympathetic reference of farmers is a bit out of keeping with the rest of his remarks. Indeed, farmers had already been a protected class before 1920, and the situation only got worse when Franklin Roosevelt’s administration implemented the Agricultural Adjustment Acts of the 1930s, which cartelized farming. But for all her indignation, Lepore never explains what is wrong with Harding’s agenda. She merely rejects it out of hand, while mocking Harding’s conviction.

Given her doggedly progressive premises, Lepore may have predicted a calamitous meltdown in the American economy under Harding, but exactly the opposite occurred. Harding appointed an exceptionally strong cabinet that included as three of its principal luminaries Charles Evans Hughes as Secretary of State, Andrew Mellon as Secretary of Treasury, and Herbert Hoover as the ubiquitous Secretary of Commerce, with a portfolio far broader than that position manages today. And how did they perform? Lepore does not mention that Harding coped quickly and effectively with the serious recession of 1921 by refusing to follow Hoover’s advice for aggressive intervention. Instead, Harding initiated powerful recovery by slashing the federal budget in half and reducing taxes across the board. Both Roosevelt and Obama did far worse in advancing recovery with their more interventionist efforts.

To her credit, Lepore notes the successes of Harding’s program: the rise of industrial production by 70 percent, an increase in the gross national product by about 40 percent, and growth in per capita income by close to 30 percent between 1922 and 1928. But, she doesn’t seem to understand why that recovery was robust, especially in comparison with the long, drawn-out Roosevelt recession that lingered on for years when he adopted the opposite policy of extensive cartelization and high taxes through the 1930s.

Lepore is on sound ground when she attacks Harding and Coolidge for their 1920s legislation that isolated the American economy from the rest of the world. The Immigration Act of 1924 responded to nativist arguments by seriously curtailing immigration from Italy and Eastern Europe, subjecting millions to the ravages of the Nazis a generation later. Harding and Coolidge also increased tariffs on imports during this period. What Lepore never quite grasps is that any critique of these actions rests most powerfully on the classical liberal worldview that she rejects. Indeed, Harding and Coolidge exhibited the same intellectual confusion that today animates Donald Trump, who gets high marks for supporting deregulation and tax reductions at home, while simultaneously indulging in unduly restrictive immigration policies and mercantilist trade wars abroad. Analytically, however, the same pro-market policies should control both domestically and abroad. Hoover never got that message — as president, he signed the misguided Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 that sharply reduced the volume of international trade to the detriment of both the United States and all of its trading partners, which helped turn what had been a short-term stock market downturn in 1929 into the enduring Great Depression of the 1930s.

October 29, 2017

QotD: Mencken’s revised view of Coolidge

In what manner he would have performed himself if the holy angels had shoved the Depression forward a couple of years — this we can only guess, and one man’s hazard is as good as another’s. My own is that he would have responded to bad times precisely as he responded to good ones — that is, by pulling down the blinds, stretching his legs upon his desk, and snoozing away the lazy afternoons…. He slept more than any other President, whether by day or by night. Nero fiddled, but Coolidge only snored…. Counting out Harding as a cipher only, Dr. Coolidge was preceded by one World Saver and followed by two more. What enlightened American, having to choose between any of them and another Coolidge, would hesitate for an instant? There were no thrills while he reigned, but neither were there any headaches. He had no ideas, and he was not a nuisance.

H.L. Mencken, The American Mercury, 1933-04.

March 17, 2016

Coolidge: The Best President You Don’t Know

Published on 4 May 2015

Americans today place enormous pressure on presidents to “do something”…anything, to get the economy going. There was one president, though, Calvin Coolidge, who did “nothing” — other than shrink government. What happened? America’s economy boomed. Is there a lesson to be learned? Award-winning author, historian, and biographer Amity Shlaes thinks so.

September 21, 2014

The Roosevelts and the foundation of the Imperial Presidency

Amity Shlaes on the recent Ken Burns documentary on Teddy Roosevelt, FDR, and Eleanor Roosevelt:

“He is at once God and their intimate friend,” wrote journalist Martha Gellhorn back in the 1930s of President Franklin Roosevelt. The quote comes from The Roosevelts, the new Ken Burns documentary that PBS airs this month. But the term “documentary” doesn’t do The Roosevelts justice. “Extravaganza” is more like it: In not one but 14 lavish hours, the series covers two great presidents, Theodore Roosevelt, who served in the first decade of the last century, and Franklin Roosevelt, who led our nation through the Great Depression and to victory in World War II. In his use of the plural, Burns correctly includes a third Roosevelt: Eleanor, who as first lady also affected policy, along with her spouse.

[…]

Absent, however, from the compelling footage is any display of the negative consequences of Rooseveltian action. The premise of Theodore Roosevelt’s trustbusting was that business was too strong. The opposite turned out to be true when, bullied by TR, the railroads promptly collapsed in the Panic of 1907. In the end it fell to TR’s very target, J. P. Morgan, to organize the rescue on Wall Street.

The documentary also neglects to mention that the economy of the early 1920s proved likewise fragile — casualty, in part, to President Woodrow Wilson’s fortification of TR’s progressive policies. Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge poured their own energy into halting the expansion of an imperial presidency and sustaining the authority of the states. This endeavor, anti-progressive, also won approbation: In 1920, the Harding-Coolidge ticket beat Cox-Roosevelt. The result of the Harding-Coolidge style of presidency was genuine and enormous prosperity. The 1920s saw the arrival of automobiles, indoor toilets, and the very radios that FDR would later use so effectively to his advantage. Joblessness dropped; the number of new patents soared. TR had enjoyed adulation, but so did his mirror opposite, the refrainer Coolidge.

When it comes to the 1930s, such twisting of the record becomes outright distortion. By his own stated goal, that of putting people to work, Roosevelt failed. Joblessness remained above 10 percent for most of the decade. The stock market did not come back. By some measures, real output passed 1929 levels monetarily in the mid 1930s only to fall back into a steep depression within the Depression. As George Will comments, “the best of the New Deal programs was Franklin Roosevelt’s smile.” The recovery might have come sooner had the smile been the only New Deal policy.

So great is Burns’s emphasis on the Roosevelt dynasty that William Howard Taft, Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover come away as mere seat warmers in the White House. Especially puzzling is the neglect of TR’s progressive heirs, Taft and Wilson, who, after all, set the stage for FDR. This omission can be explained only by Burns’s desire to cement the reign of the Roosevelts. On the surface, the series’ penchant for grandees might seem benign, like the breathless coverage of Princess Kate’s third trimester in People magazine. In this country, elevating presidential families is a common habit of television producers; the Kennedys as dynasty have enjoyed their share of airtime. Still, Burns does go further than the others, ennobling the Roosevelts as if they were true monarchs, gods almost, as in Martha Gellhorn’s above mentioned line. Burns equates progressive policy with the family that promulgates it. And when Burns enthrones the Roosevelts, he also enthrones their unkingly doctrine, progressivism.

May 22, 2014

How politicians are like soccer goalkeepers

At Worthwhile Canadian Initiative, Stephen Gordon talks about the odd distribution of goalie decisions on penalty kicks and how they’re quite similar to politicians:

Goaltenders jumped in more than 90% penalty kicks in the sample: the frequency of staying put was only 6.3%. Kickers, on the other hand, distributed their targets in roughly equal proportions.

The goaltenders’ strategy was not wholly ineffective: when the kicker aimed left or right (71.4% of the time), goaltenders guessed correctly 6 times out of 11. But the fact remains that the frequency of the goaltender staying put (6.3%) is much smaller that the frequency of kicks aimed down the middle (28.7%).

[…]

This doesn’t mean that goaltenders should never jump. What it does mean is that goaltenders jump far too often. Why?

Bar-Eli et al suggest an explanation: ‘action bias’. This is presented as an example of Kahneman and Miller’s (1986) [PDF] ‘norm bias’. Goaltenders believe is is less bad to follow the ‘norm’ (i.e., to jump) and fail than to not jump and fail. In other words, goaltender think that jumping and missing is less costly than not jumping and missing.

Which brings us to economic policy. Politicians are continually demanded to ‘do something’ about a kaleidoscopic array of grievances, and the norm in these cases is to promise to do something. As far as politicians and most voters are concerned, doing something is better than doing nothing — even when doing nothing is the correct response.

In many cases — possibly the majority of cases — doing nothing is the smart move. A recent example is the concern about the so-called ‘skill shortage’. When firms complain that they can’t get the workers they want at the wages they are willing to pay, the correct response is to do nothing: the market response to a labour shortage is to let wages increase.

But doing nothing is almost always bad politics: it is invariably interpreted as a lack of concern, and this perceived indifference will be pounced upon by other political parties. A politician who promises to act polls better than one who promises to do nothing.

A goalkeeper who fails to jump looks like an idiot if the ball goes left or right. The fans roar their disapproval and the keeper learns that doing the dramatic-but-wrong thing is better for his reputation than the non-dramatic (but more likely to be correct) non-action. Politicians also learn that the media will turn themselves purple denouncing the lack of action (even when that’s the correct decision) and short-term polling numbers move in the wrong direction.

As Calvin Coolidge is reported to have said, “Don’t just do something; stand there.” But even if you’re right not to take action, it will be harder to bear up under the criticism of the “do something” crowd.

February 23, 2014

Visiting the grave of Calvin Coolidge

I missed this post earlier in the week, as Mark Steyn briefly talks about visiting the grave of the 30th president in Plymouth Notch, Vermont:

Presidents are thin on the ground in my corner of New Hampshire. There’s Franklin Pierce down south, and Chester Arthur over in western Vermont (or, for believers in the original birther conspiracy, southern Quebec), but neither is any reason for a jamboree. So, for a while around Presidents Day, I’d drive my kids over the Connecticut River and we’d zig-zag down through the Green Mountain State to the Coolidge homestead in Plymouth Notch. And there, with the aid of snowshoes, we’d scramble up the three-foot drifts of the village’s steep hillside cemetery to Silent Cal’s grave. Seven generations of Coolidges are buried there all in a row — including Julius Caesar Coolidge, which is the kind of name I’d like to find on the ballot one November (strong on war, but committed to small government). The 30th president is as seemly and modest in death as in life, his headstone no different from those of his forebears or his sons — just a plain granite marker with name and dates: in the summer, if memory serves, there’s a small US flag in front, and there’s no snow so that, under the years of birth and death, you can see the small American eagle that is all that distinguishes this man’s gravestone from the earlier Calvin Coolidges in his line.

I do believe it’s the coolest grave of any head of state I’ve ever stood in front of. It moves me far more than the gaudier presidential memorials. “We draw our presidents from the people,” said Coolidge. “I came from them. I wish to be one of them again.” He lived the republican ideal most of our political class merely pays lip service to.

I came to Plymouth Notch during my first winter at my new home in New Hampshire, and purchased some cheddar from the village cheese factory still owned by his son John (he sold it in 1998). So, ever afterwards, the kids and I conclude our visit by swinging by the fromagerie and buying a round of their excellent granular curd cheese.

I just finished reading Amity Shlaes’ recent biography of Coolidge (highly recommended, by the way), and I have to admire a man who was able to walk away from the presidency despite the loud demands of his party to run again (and was almost certain to be re-elected if he had chosen to run). Coolidge was the last of the strong advocates for small government to occupy the White House. His immediate successor was very much the opposite: many of the big government ideals of FDR were strongly prefigured in the life and works of Hoover, despite later historians’ claims that Hoover was all about laissez faire economics.

May 27, 2013

QotD: Two lessons from Calvin Coolidge

I managed to talk for more than 15 minutes, but I could have boiled my remarks down to these two points.

- Small government is the best way to achieve competent and effective government. Coolidge and his team were able to monitor government and run it efficiently because the federal budget consumed only about 5 percent of GDP. But when the federal budget is 23 percent of GDP, by contrast, it’s much more difficult to keep tabs on what’s happening – particularly when the federal government operates more than 1,000 programs. Even well-intentioned bureaucrats and politicians are unlikely to do a good job, […]

- Higher tax rates don’t automatically lead to more tax revenue. Coolidge and his Treasury Secretary practiced something called “scientific taxation,” but it’s easier just to call it common sense. Since Amity’s book covered the data from the 1920s, I shared with the audience some amazing data from the 1980s showing that lower tax rates on the “rich” led to big revenue increases.

Dan Mitchell, “Two Lessons from Calvin Coolidge”, International Liberty, 2013-05-26