World War Two

Published 2 Mar 2024Bill Slim’s master plan is near fruition and the Japanese are surrounded at Meiktila in Burma. The Allies have also nearly cleared Manila on Luzon, but the fighting on Iwo Jima is just growing in intensity. In Europe, the Soviets are still on the move in Poland, though attacking now to the north, but in Hungary it’s the Germans who are making plans for a new offensive. The big news on the Western Front is the Allies reaching the Rhine, though how they’ll cross that mighty river is anyone’s guess.

(more…)

March 3, 2024

Allied Deception Surrounds Japanese in Burma – WW2 – Week 288 – March 2, 1945

March 2, 2024

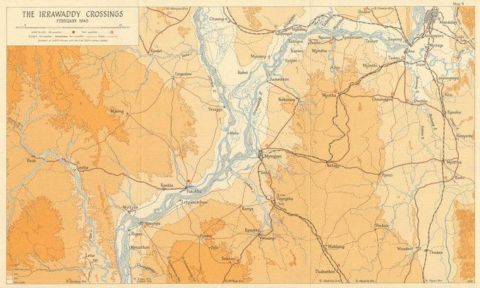

Crossing the Irrawaddy

Dr. Robert Lyman is on a visit to the site of a very significant event in the battle for Burma in 1945:

On 13-14 February 1945, 79-years ago this month the 7th Indian Division commanded by Major General Geoffrey Evans secured crossings over the Irrawaddy at Pakkoku and Nyaung-U/Bagan. The northern crossing (Pakkoku) was designed to allow Punch Cowan’s 17th Indian Division, and the Sherman tanks of 255 Indian Tank Brigade, to race across country to seize Meiktila. The southern ones, at Nyaung-U and Bagan (a few miles to the south still), were designed to prevent the enemy from interfering with the operations against Meiktila, and to make him believe that securing the Irrawaddy as a route to Rangoon — and not Meiktila — was Slim’s primary objective. In 2005, for the 60th anniversary of the Irrawaddy crossings, I was privileged to walk the battlefield with three veterans of these crossings, John Chiles (Probyn’s Horse), Manny Curtis (South Lancashire Regiment) and Bert Wilkins (RA, in support of the South Lancs). During that trip we travelled along the Irrawaddy from Bagan, anxiously scouring the maps in the South Lancs’ War Diary searching for B4 beach, where on the early morning of 14 February 1945 two hundred men of 2nd Battalion South Lancashire Regiment had rowed silently across the river to form the vanguard of the 7th Indian Division beachhead. I remember vividly the excitement as we found B4 — it was much easier than I had thought — disembarked from the boat and climbed to the top of the cliffs to find old trenches from the battle. It was an emotional event for the veterans as they recalled the battle and found trenches left by the defenders decades before.

At Nyaung-U the first wave of a company of the 2nd Bn South Lancs (including Manny Curtis) managed to seize the high ground above B4 in the early morning of 14 February. It was the longest opposed river crossing in any theatre of the Second World War. The beaches had been recced by a Sea Reconnaissance Unit and a Special Boat Section. However, subsequent waves of troops from the remainder of the South Lancs, the 4th Battalion 14th Punjab Regiment and the 4th Battalion 1st Gurkha Rifles were mauled by enemy machine gun fire as the leaky canvas boats and temperamental outboard motors failed to cope with the distance they had to cover and the strength of the river’s flow. The enemy? Pagan and Nyaungu were defended not by the Japanese but by three battalions of the Indian National Army’s 4th Guerrilla Regiment, some 2,000 men in well-sited positions overlooking the Irrawaddy. This was the only major engagement of the war when troops of the Indian Army fought in direct combat against the INA. To subdue the enemy positions causing casualties on the water, Sherman tanks of the Gordon Highlanders sniped the enemy positions, and an artillery bombardment by 25-pdrs and a Hurribomber strike pummelled the east bank of the river. Together these actions succeeded in forcing the INA to surrender. Further to the west, at Pagan, the INA’s 9th Battalion took a heavy toll of the assaulting 1/11th Sikh Regiment, before they withdrew to Mount Popa to the rear. River crossing are dangerous, especially for troops with little training in boatmanship, across one of the world’s greatest rivers. But this time the 7th Indian Division succeeded with little training or preparation. By the end of the day the east bank was in its hands. Amazingly, a cinematographic unit were available to film some of the crossings at Nyaung-U. An 8-minute reel of the landings can be seen in the IWM on JFU35.

Today I was able to revisit B4. Not much had changed in nearly 20-years. The size of the Irrawaddy even in the dry season is astonishing, the task given to the men of 33 Brigade enormous. In 2005 we climbed the cliffs that Manny and his friends had raced up in 1945. Looking at them again today, I realised just how Gallipoli-like was the terrain. In the hands of of better trained enemy, 33 Brigade should never have managed to get off the beachhead. Rippling rows of gullies flow behind the initial landing site: if these had all been defended, a position of great depth and near impregnability could have been achieved. These photos look down on B4 and across to the position up which the men of 2nd South Lancs scrambled.

February 25, 2024

Iwo Jima! – WW2 – Week 287 – February 24, 1945

World War Two

Published 24 Feb 2024This week the Battle of Iwo Jima begins and American forces raise the Stars and Stripes on Mount Suribachi. Elsewhere, the Allies fight the stiff Japanese defences in Manila. The Red Army continues fighting through East Prussia and Pomerania as Stalin plans the next stage of the advance on the Reich. There are Allied advances in Western Europe and Italy too.

00:01 Intro

00:54 Recap

01:16 Iwo Jima Begins

06:32 The war in the Philippines

07:56 The Battle of Manila

11:12 Fighting in Burma

12:14 Operation Grenade

13:46 Operation Encore

14:38 Soviet plans for new offensives

21:28 Moscow Commission Meets

(more…)

February 18, 2024

German Counterattack in Pomerania – WW2 – Week 286 – February 17, 1945

World War Two

Published 17 Feb 2024The Germans finally launch a counterattack into the Soviet flanks, but it does not go as well as was as hoped. The Siege of Budapest comes to an end, also not well for the Germans. The Soviets have now also surrounded Breslau. In Burma, the Allies cross the Irrawaddy River, in the Philippines the fight for Manila continues, and in the Pacific preparations are underway for an American invasion of Iwo Jima Island.

01:50 The fight for East Prussia

04:08 German counterattack in Poland

07:00 Breslau Surrounded

07:57 The Siege of Budapest

09:14 Operation 4th Term in Italy

10:07 Operation Veritable Continues

11:36 Allies cross the Irrawaddy

14:43 The Fight in the Philippines

17:52 Preparations for Iwo Jima

(more…)

February 11, 2024

The Battle of Manila Begins – WW2 – Week 285 – February 10, 1945

World War Two

Published 10 Feb 2024The American advance on Luzon has reached the Philippine capital, and it looks like they have a real fight on their hands with the Japanese there. There are supposed to be two new Allied operations starting in Western Europe, but one is delayed by flooding. The Allies do manage to eliminate the Colmar Pocket in the west, though. On the Eastern Front, there are new Soviet attacks in Pomerania and East Prussia, as well as out of the Steinau Bridgehead to the south, and in Budapest, it looks like the Soviet siege might soon end in victory.

(more…)

February 4, 2024

Is the Red Army too fast for its own good? – WW2 – Week 284 – February 3, 1945

World War Two

Published 3 Feb 2024Soviet forces have reached the old German border in force, however, logistical issues and a strong enemy presence possibly threatening their flanks means that a drive on Berlin may not be doable just now. Heinrich Himmler is in charge of the new Army Group to defend the Reich, and he has a host of problems. On the Western Front, the Allies finally eliminated the Colmar Pocket, and in the Philippines, the American advance reaches Manila, and the battle for the city is about to begin.

(more…)

February 1, 2024

The Kohima Epitaph: Britain’s Forgotten Battle That Changed WW2

The History Chap

Published 9 Nov 2023What is the Kohima Epitaph and what has it got to do with Britain’s forgotten battle that changed the Second World War? Well, those of you living in the UK and who attend Remembrance Sunday services will probably know the words even if you don’t know the story behind them:

“When you go home, tell them of us and say,

For your tomorrow, We gave our today.”The memorial which bears those powerful words, stands in a cemetery containing the graves over over 1,400 British servicemen and memorials to over 900 Indian troops who died alongside them. They died in one of the bloodiest, toughest, grimmest battles of the Second World War. A battle sometimes called the “Stalingrad of the East.”

Outnumbered 6:1 and half of whom were from non-combat units, the multi-national British garrison stood their ground in bloody hand-to-hand fighting, refusing to retreat or surrender for two weeks until relieved. And even then the battle continued for another vicious month. That stand stopped the Japanese invasion of India in its tracks and turned the tide of the war in South East Asia. Both for its ferocity and its turning point in the war, it has been called: “Britain’s greatest battle”.

The Japanese lost 53,000 men from their army of 85,000.

The British (14th Army) lost 4,000 men killed and wounded.This forgotten victory was made possible by General William (Bill) Slim commanding the 14th Army. Rather like the battle and the 14th Army, General Slim has not received the recognition that he is due. And yet, it is almost completely forgotten. Rather like the army that fought against the Japanese in Burma.

So, as we near Remembrance Sunday, I think it is time to reveal the story of the Battle of Kohima in 1944.

(more…)

January 28, 2024

Himmler Takes Command – WW2 – Week 283 – January 27, 1945

World War Two

Published 27 Jan 2024A new German Army Group has been formed, tasked with protecting the Reich from the east and commanded by none other than Heinrich Himmler, who has never held such a command. The Soviets are really on the move in the east and have even begun reaching the prewar German border. In the west the Allies have cleared the Roer Triangle and are also working hard to eliminate the Colmar Pocket. In the Far East the Americans are advancing on Luzon, and in Burma the Allies have success on the Arakan and the Shwebo Plain, and finally manage to re open the Burma Road with China.

01:27 Soviet advances in East Prussia

09:23 Hungary and the fight for Buda

11:19 Operations Nordwind, Cheerful, and Blackcock

14:23 Block 5

16:14 American advances on Luzon

18:55 Allied successes in Burma

22:06 Summary

22:26 Conclusion

(more…)

January 23, 2024

The battle of Sangshak, 1944

Dr. Robert Lyman discusses a new book by David Allison that covers one of the many small battles that made up the large Imphal-Kohima campaign:

When Wavell, by then Viceroy of India, visited Imphal after the battle in October, to bestow knighthoods on the four victors — Lieutenant Generals Bill Slim (14 Army), Montagu Stopford (33 Corps), Geoffrey Scoones (4 Corps) and Philip Christison (15 Corps) — he admitted to Slim that he found the battle hard to follow, as it seemed to have been fought in “penny-packets”. In professing his ignorance of Slim’s great triumph, Wavell nevertheless hit the nail on the head. Sangshak was one of those penny-packet fights which cumulatively determined the outcome of Japan’s audacious invasion of India.

Like many battles in insufficiently examined wars, Sangshak has suffered over the years from a paucity of rigorous examination. Louis Allen’s magisterial The Longest War gave it short treatment in 1984, and very little else. Until now. I’m delighted to say that a Hong Kong-based Australian lawyer with a military background — David Allison — has produced a new account of this crucial battle, and it is absolutely outstanding. It can be purchased here. I recommend it very strongly. It’s not long: at 159-pages of text you can make your way through this in a couple of days, but it is diligently researched, well written and judiciously argued. For those who know something of the battle, the big arguments in the past about the state training of the 50 Indian Parachute Brigade, the temporary breakdown of its commander, Hope-Thomson and the supposed loss of the captured Japanese map and orders by HQ 23 Indian Division, are calmly and satisfyingly explained.

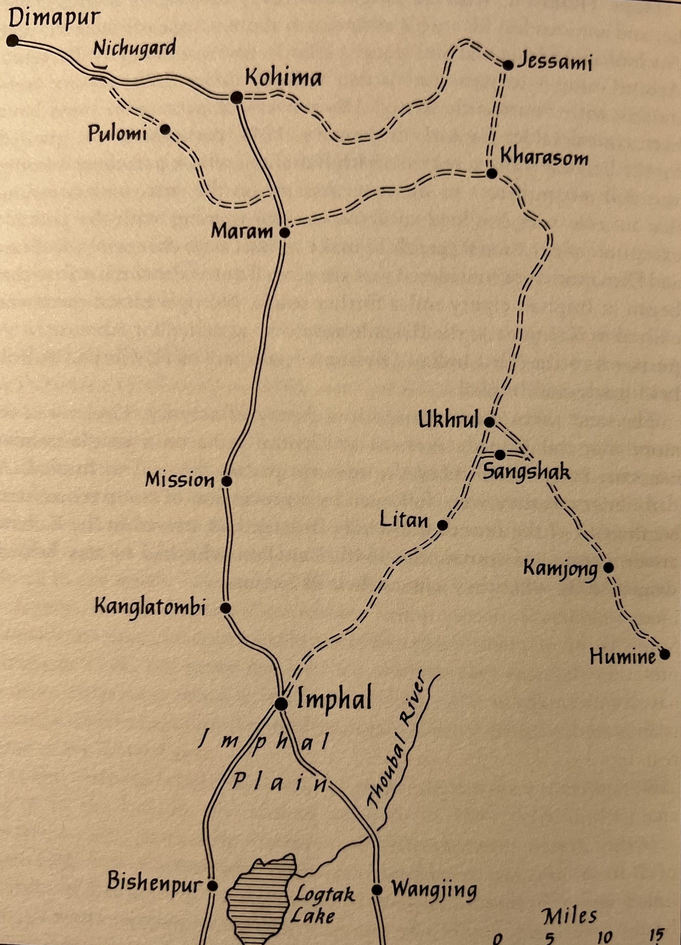

The story can be briefly told. The territory to the north-east of Imphal (centring on the Naga village of Ukhrul) had only the lightest of garrisons and no real defences. Until 16 March it was home to 49 Brigade, which was then despatched to the Tiddim Road to deal with the advance in the south of Lieutenant General Yanagida’s 33 Division. The brigade had considered itself to be in a rear area, and, extraordinarily, no dug-in and wired defensive positions had been prepared. It was one of the most serious British planning failures of the campaign. The entire north-eastern portion of Imphal lay effectively undefended. The gap left by the brigade’s departure had been filled in part by the arrival of the first of the two battalions of the newly raised 50 Indian Parachute Brigade (comprising the Gurkha 152 Battalion and the Indian 153 Battalion), whose young and professional commander, 31-year-old Brigadier M.R.J. (“Tim”) Hope-Thomson, had persuaded New Delhi to allow him to complete the training of his brigade in territory close to the enemy. The area north-east of Imphal was regarded as suitable merely for support troops and training. At the start of March, the brigade HQ and one battalion had arrived in Imphal and began the leisurely process of shaking itself out in the safety of the hills north-east of the town. To the brigade was added 4/5 Mahrattas under Lieutenant Colonel Trim, left behind when 49 Brigade was sent down to the Tiddim Road. To Scoones and his HQ, the area to which Hope-Thomson and his men were sent represented the lowest of all combat priorities. Sent into the jungle almost to fend for themselves, it was not expected that they would have to fight, let alone be on the receiving end of an entire Japanese divisional attack. They had little equipment, no barbed wire, and little or no experience or knowledge of the territory. No one considered it worthwhile to keep them briefed on the developing situation. To all intents and purposes, 50 Indian Parachute Brigade was an irrelevant appendage, attached to Major General Ouvry Roberts’ 23 Indian Division for administrative purposes but otherwise left to its own devices.

Before long, information began to reach Imphal that Japanese troops were advancing in force on Ukhrul and Sangshak. Inexplicably, however, this information appeared not to ring any warning bells in HQ IV Corps in Imphal, which was preoccupied with the developing threat in the Tamu area where the main Japanese thrust was confidently predicted. On the night of 16 March, the single battalion of 50 Parachute Brigade took over responsibility for the Ukhrul area from 49 Brigade, which was hastily departing for the Tiddim Road. They had no idea that an entire Japanese division of 20,000 men was crossing the Chindwin in strength opposite Homalin. On 19 March, large columns of Japanese infantry were reported advancing through the hills.

No one had expected them to be where they were. But the first shock came to the Japanese 3/58 battalion (Major Shimanoe), part of Lieutenant General Sato’s 31 Division – troops whose objective was Kohima, and not Imphal – who were bloodily rebuffed by the determined opposition of the young Gurkha soldiers at an unprepared position forward of Sheldon’s Corner. The 170 Gurkha recruits refused to allow the 900 men of 3/58 to roll over them and inflicted 160 casualties on the advancing Japanese. In the swirling confusion of the next 36 hours, Hope Thomson and his staff kept their heads, attempting to concentrate what remained of the dispersed companies of 152 Battalion and 4/5 Mahrattas back to a common position at the village of Sangshak, which dominated the tracks southwest to Imphal.

It was at this now-deserted Naga village that Hope-Thomson, on 21 March, decided to group his brigade for its last stand, his staff desperately attempting to alert HQ 4 Corps in Imphal to the enormity of what was happening to the north-east. The Japanese columns infiltrated quickly around and through the British positions, heading in the direction of Litan. The Japanese now began days of repeated assaults on the position in a battle of intense bravery and sacrifice for both sides. Hope Thomson’s men could only dig shallow trenches, which provided no protection from Japanese artillery.

January 14, 2024

Soviet and American Massive Attacks – Week 281 – January 13, 1945

World War Two

Published 13 Jan 2024In the East, the Soviets launch a massive series of new offensives. In the West, Monty holds an ill-judged press conference about the Battle of the Bulge. Operation Nordwind, the German offensive in Alsace, continues. In Hungary, there’s house to house fighting as the Red Army besieges Budapest. In Asia, the Allies wrestle with the Kamikazes, begin their landings on Luzon, and advance in Burma.

00:54 Intro

01:12 Recap

01:22 Montgomery’s Press Conference

05:53 Operation Nordwind

07:07 The battle for Hungary

09:38 The huge Soviet offensive begins!

12:22 American landings on Luzon

15:29 Anti-Kamikaze tactics

18:11 Slim’s advance in Burma

21:11 Conclusion

(more…)

December 17, 2023

The Battle of the Bulge Begins – WW2 – Week 277 – December 16, 1944

World War Two

Published 16 Dec 2023Adolf Hitler’s Ardennes counteroffensive finally goes off this week, and it does indeed catch the Allies by surprise, and they suspend other offensive operations in the west. They are still attacking in Italy, and the Soviets are still advancing in Hungary, trying to cut off Budapest. In the Far East, there are Allied landings on Mindoro, and they are also on the march in Burma, hoping to pin down the enemy.

0:00 Intro

0:55 Recap

1:22 Street fighting in Athens

04:07 Operation Queen ends

06:33 Autumn Mist Offensive plans

09:51 Allied intelligence failures

12:26 The Ardennes Offensive Begins

16:57 Allied attacks in Italy and Soviet plans to surround Budapest

20:07 The Allied offensive in Burma

22:10 Mindoro Landings

24:33 Summary

25:14 Conclusion

(more…)

November 26, 2023

General Patton’s Metz Obsession – WW2 – Week 274 – November 25, 1944

World War Two

Published 25 Nov 2023Metz finally falls to Patton’s 3rd Army, but boy, it’s taken some time. To the south, the Allies also take Belfort and Strasbourg, and to the north Operation Queen continues trying to reach the Roer River. The Soviets complete their conquest of the islands in the Gulf of Riga and continue advancing in Hungary to the south, but it’s the Axis Powers — the Japanese — who are advancing in China, taking Dushan and Nanning.

01:15 Operation Queen Continues

04:49 9th Army attacks toward the Roer

05:54 Pattons 3rd Army takes Metz

09:22 Allies take Belfort, Mulhouse, and Strasbourg

13:56 8th Army Attacks in Italy

15:42 Soviet advances and German indecision

18:05 Japanese take Dushan and Nanning

19:21 The fight for Peleliu ends

21:43 Notes from all over

22:23 Conclusion

(more…)

October 24, 2023

See Inside The M3 Grant | Tank Chats Reloaded

The Tank Museum

Published 30 Jun 2023With a crew of six and a chaotically crowded interior, the Grant was a US-produced WW II tank more used by the British and Indian Armies than anyone else. Join Chris Copson as he explores probably the best preserved example of this rare vehicle – and listen out for the cheese sandwich …

(more…)

September 15, 2023

Learning to handle mules to accompany Chindit columns in WW2

Robert Lyman posted some interesting details from veteran Philip Brownless of how British troops in India had to learn how to handle mules and abandon their motor transport in order to get Chindit columns into Japanese territory in Burma:

Soon after our return from the Arakan front in the autumn of 1943, we were in central India, and had been told that the whole division was to be handed over to General Wingate and trained to operate behind the Japanese lines. All our motor transport was to be taken away and we were to be entirely dependent upon mules for our transport.

The C.O. one evening looked round the mess and then said to me “You look more like a country bumpkin than anybody else. You will go on a veterinary course on Tuesday and when you come back you will take charge of 44 Column’s mules.”

I had never met one of these creatures before. On arriving at Ambala I reported to the Area Brigade Major who wasn’t expecting me and seemed to have no clue about anything. He said “You’d better go down to the Club and book in”. I reported to the Club, a comfortable looking establishment, and they seemed to have a vague idea that a few bodies like me might turn up on a course and were apologetic that I would have to sleep in a tent but otherwise could enjoy the full facilities of the Club. I was shown the tent, an EPIP tent or minor marquee, with a coloured red lining and golden fleur de lys all over it, (very Victorian) with a small office extension with table and chair in front and another extension at the back with bath, towel rail and a fully bricked floor. Having lived either in a tent or under the stars in both the desert and the Arakan for the last 2 years, this struck me as luxury indeed. Even better, I took on a magnificent bearer, with suitable references, whom I found later was some kind of Hindu priest. I soon got used to having my trouser legs held up for me to put my feet in, and being helped into the rest of my clothes. I had a comfortable 3 weeks learning all about mules.

I discovered all sorts of things like the veterinary term “balls”, which were massive pills which were given to the mule by – first of all grabbing his tongue and pulling it out sideways so he couldn’t shut his mouth on your arm, and then gently throwing the ball at his epiglottis and making sure it went down. Then you let go of his tongue and gave him a nice pat. One of our lecturers, an Indian warrant officer, knew his stuff well and was so pleased about it that when he asked a question he would give you the answer himself. He liked being dramatic and loved to finish a description of some fatal ailment by saying “Treatment, bullet”.

Many of the men in our battalion were East Enders; others came from all over Essex. A few were countrymen, two were Irish and knew all about horses, one sergeant had been in animal transport and one invaluable soldier had been an East End horse dealer. The large majority had had nothing to do with animals: however, the saving grace was that English soldiers seem to be naturally good with animals and soon learned to handle them well. I arranged to get some instruction from the nearby unit of Madras Sappers and Miners and we borrowed a handful of trained mules from them for the men to practise handling, tying on loads and learning to talk to them.

Then came the great day when we were to draw up our main complement of animals, about 70 mules and 12 ponies. We were dumped at a small railway station. It was all open ground and there was a team of Army Veterinary Surgeons to allocate fairly between the three battalions, the Essex, the Borders and the Duke of Wellington’s. Lieut. Jimmy Watt of the Borders was a pal of mine: he and I, with a squad of men were to march them back nearly 100 miles to our camp, sleeping each of the five nights under the stars. As soon as we arrived at the disembarkation site I got all our mule lines laid out, with shackles (used to tie mules fore and aft) and nosebags ready. I had also picked up the tip that the mules would be wild, having spent three days in the train, and almost impossible to hold, so I instructed our men to tie them together in threes before they got off the train. As all three pulled in different directions, one muleteer could hold them. Not everybody had learned this trick so the result was that wild mules were careering all over the place, impossible to catch. When our first handful of mules arrived, they were quickly secured in a straight line and fed. They were familiar with lines like this and cooled down at once, long ears relaxed and tails swishing amiably. When the wild mules careering round saw this line, they said to themselves “We’ve done this before” and came and stood in our lines. We shackled them and I picked out the moth-eaten ones and sent them back to the vets who kept sending polite messages of thanks to Mr. Brownless for catching them. We finished up with a very good set of mules. Jimmy Watt and I had a bit of a conscience about the Duke of Wellington’s so we picked them out a really good pony. We felt even worse a few weeks later when it was sent back to Remounts with a weak heart! The Brigade Transport Officer visited us the second evening so Jimmy Watt and I walked him round rather quickly, chatting hard, to approve the allocation of animals, and he agreed with our arrangement.

In a highly optimistic mood early on, I decided to practise a river crossing. We marched several miles out from camp to a typical wide sandy Indian river, 300 yards across, made our preparations, i.e. assembling the two assault boats, making floating bundles of our clothes and gear by wrapping them in groundsheets, unsaddling the animals, and assembling at the water’s edge. A good sized detachment of muleteers was posted on the opposite bank ready to catch the mules. The mules waded into the shallow water but no one could get them to move off. We tried all sorts of inducements in vain and then suddenly, one sturdy little grey animal decided to swim and the whole lot immediately followed. Calamity ensued! Mules are very short sighted and could only dimly see the opposite bank but downstream was a bright yellow sandy outcrop and they all made for this. The muleteers on the other bank, when they realised what was happening, ran through the scrub and jungle as fast as they could, but the mules arrived first and bolted off into the wilds of India. I swam my pony across with my arm across his withers and directing him by holding his head harness, the gear was ferried across and the mule platoon, with one pony, began the march back to camp. Deeply depressed, I wondered how to tell the C.O. I had lost all his mules and imagined the court martial which awaited me (or, serving under General Wingate, would I be shot out of hand?) An hour and a half later we came in sight of the camp and to my utter astonishment I could see the mules in their lines. When I arrived at the mule lines, the storeman met me and said that the whole lot had arrived at the double and had gone to their places. He had merely gone along the lines, shackling them and patted their noses. Salvation! I kept quiet for a bit but it got out and I was the butt of much merrymaking.

August 6, 2023

The Warsaw Uprising Begins! – WW2 – Week 258 – August 5, 1944

World War Two

Published 5 Aug 2023As the Red Army closes in on Warsaw, the Polish Home Army in the city rises up against the German forces. Up in the north the Red Army takes Kaunas. The Allies take Florence in Italy this week, well, half of it, and in France break out of Normandy and into Brittany. The Allies also finally take Myitkyina in Burma after many weeks of siege, and in the Marianas take Tinian and nearly finish taking Guam. And in Finland the President resigns, which could have serious implications for Finland remaining in the war.

(more…)