World War Two

Published 13 Jan 2024In the East, the Soviets launch a massive series of new offensives. In the West, Monty holds an ill-judged press conference about the Battle of the Bulge. Operation Nordwind, the German offensive in Alsace, continues. In Hungary, there’s house to house fighting as the Red Army besieges Budapest. In Asia, the Allies wrestle with the Kamikazes, begin their landings on Luzon, and advance in Burma.

00:54 Intro

01:12 Recap

01:22 Montgomery’s Press Conference

05:53 Operation Nordwind

07:07 The battle for Hungary

09:38 The huge Soviet offensive begins!

12:22 American landings on Luzon

15:29 Anti-Kamikaze tactics

18:11 Slim’s advance in Burma

21:11 Conclusion

(more…)

January 14, 2024

Soviet and American Massive Attacks – Week 281 – January 13, 1945

August 3, 2023

Behind Japanese lines in Burma – SOE and Karen tribal guerillas in 1944/45

Bill Lyman outlines one of the significant factors assisting General Slim’s XIVth Army to recapture Burma from the Japanese during late 1944 and early 1945:

If Lieutenant General Sir Bill Slim (he had been knighted by General Archibald Wavell, the Viceroy, the previous October, at Imphal) had been asked in January 1945 to describe the situation in Burma at the onset of the next monsoon period in May, I do not believe that in his wildest imaginings he could have conceived that the whole of Burma would be about to fall into his hands. After all, his army wasn’t yet fully across the Chindwin. Nearly 800 miles of tough country with few roads lay before him, not least the entire Burma Area Army under a new commander, General Kimura. The Arakanese coastline needed to be captured too, to allow aircraft to use the vital airfields at Akyab as a stepping stone to Rangoon. Likewise, I’m not sure that he would have imagined that a primary reason for the success of his Army was the work of 12,000 native levies from the Karen Hills, under the leadership of SOE, whose guerrilla activities prevented the Japanese from reaching, reinforcing and defending the key town of Toungoo on the Sittang river. It was the loss of this town, more than any other, which handed Burma to Slim on a plate, and it was SOE and their native Karen guerrillas which made it all possible.

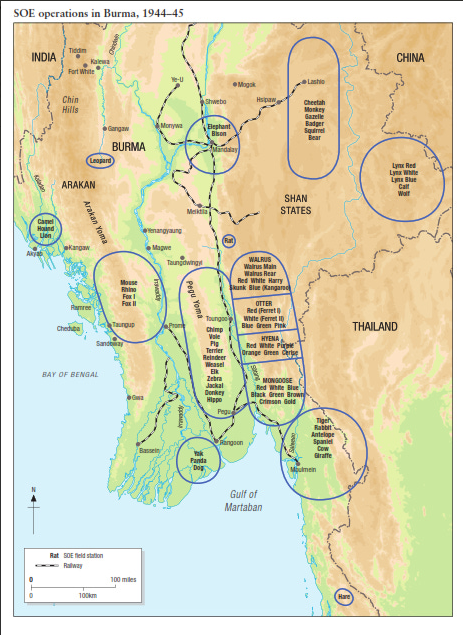

In January 1945 Slim was given operational responsibility for Force 136 (i.e. Special Operations Executive, or SOE). It had operated in front of 20 Indian Division along the Chindwin between 1943 and early 1944 and did sterling work reporting on Japanese activity facing 4 Corps. Persuaded that similar groups working among the Karens in Burma’s eastern hills – an area known as the Karenni States – could achieve significant support for a land offensive in Burma, Slim authorised an operation to the Karens. Its task was not merely to undertake intelligence missions watching the road and railways between Mandalay and Rangoon, but to determine whether they would fight. If the Karens were prepared to do so, SOE would be responsible for training and organising them as armed groups able to deliver battlefield intelligence directly in support of the advancing 14 Army. In fact, the resulting operation – Character – was so spectacularly successful that it far outweighed what had been achieved by Operation Thursday the previous year in terms of its impact on the course of military operations in pursuit of the strategy to defeat the Japanese in the whole of Burma. It has been strangely forgotten, or ignored, by most historians ever since, drowned out perhaps by the noise made by the drama and heroism of Thursday, the second Chindit expedition. Over the course of Slim’s advance in 1945 some 2,000 British, Indian and Burmese officers and soldiers, along with 1,430 tons of supplies, were dropped into Burma for the purposes of providing intelligence about the Japanese that would be useful for the fighting formations of 14 Army, as well as undertaking limited guerrilla operations. As Richard Duckett has observed, this found SOE operating not merely as intelligence gatherers in the traditional sense, but as Special Forces with a defined military mission as part of conventional operations linked directly to a military strategic outcome. For Operation Character specifically, about 110 British officers and NCOs and over 100 men of all Burmese ethnicities, dominated interestingly by Burmans mobilised as many as 12,000 Karens over an area of 7,000 square miles to the anti-Japanese cause. Some 3,000 weapons were dropped into the Karenni States. Operating in five distinct groups (“Walrus”, “Ferret”, “Otter”, “Mongoose” and “Hyena”) the Karen irregulars trained and led by Force 136, waited the moment when 14 Army instructed them to attack.

Between 30 March and 10 April 1945 14 Army drove hard for Rangoon after its victories at Mandalay and Meiktila, with Lt General Frank Messervy’s 4 Indian Corps in the van. Pyawbe saw the first battle of 14 Army’s drive to Rangoon, and it proved as decisive in 1945 as the Japanese attack on Prome had been in 1942. Otherwise strong Japanese defensive positions around the town with limited capability for counter attack meant that the Japanese were sitting targets for Allied tanks, artillery and airpower. Messervy’s plan was simple: to bypass the defended points that lay before Pyawbe, allowing them to be dealt with by subsequent attack from the air, and surround Pyawbe from all points of the compass by 17 Indian Division before squeezing it like a lemon with his tanks and artillery. With nowhere to go, and with no effective means to counter-attack, the Japanese were exterminated bunker by bunker by the Shermans of 255 Tank Brigade, now slick with the experience of battle gained at Meiktila. Infantry, armour and aircraft cleared General Honda’s primary blocking point before Toungoo with coordinated precision. This single battle, which killed over 1,000 Japanese, entirely removed Honda’s ability to prevent 4 Corps from exploiting the road to Toungoo. Messervy grasped the opportunity, leapfrogging 5 Indian Division (the vanguard of the advance comprising an armoured regiment and armoured reconnaissance group from 255 Tank Brigade) southwards, capturing Shwemyo on 16 April, Pyinmana on 19 April and Lewe on 21 April. Toungoo was the immediate target, attractive because it boasted three airfields, from where No 224 Group could provide air support to Operation Dracula, the planned amphibious attack against Rangoon. Messervy drove his armour on, reaching Toungoo, much to the surprise of the Japanese, the following day. After three days of fighting, supported by heavy attack from the air by B24 Liberators, the town and its airfields fell to Messervy. On the very day of its capture, 100 C47s and C46 Commando transports landed the air transportable elements of 17 Indian Division to join their armoured comrades. They now took the lead from 5 Indian Division, accompanied by 255 Tank Brigade, for whom rations in their supporting vehicles had had been substituted for petrol, pressing on via Pegu to Rangoon.

July 13, 2023

Bill Slim’s plan for the Battle of Meiktila in March 1945

Dr. Robert Lyman on the subject of his most recent book, The Reconquest of Burma 1944-45: From Operation Capital to the Sittang Bend:

When I was writing my latest book with General Lord Dannatt he said to me, “Rob, if I’ve got one criticism of A War of Empires it’s that you don’t emphasise enough the role of Bill Slim in coming up with the plan for victory in 1945, and executing it perfectly.” Fair. As Slim’s military biographer, I told Richard that I didn’t want to be accused of rewriting that book again. I was conscious of this problem as I was writing A War of Empires.

But it is fair criticism. It may be that I underplayed Slim’s role when I was considering all the other critical features in this great campaign. The idea behind the dramatic victory by 14th Army in Burma in 1945 was Slim’s and Slim’s alone. He pursued his own plan through to its remarkable conclusion.

[…]

Slim’s original plan was to fight the main strength of the Japanese army on the Shwebo Plain, a dry, flat plain between the loops of the Chindwin and Irrawaddy. Not only would the terrain be well suited to the deployment of armour, for which the Japanese had little effective reply, but the Japanese would be trapped with the river-line at their back. Slim had assumed that the Japanese would be unprepared to make a voluntary withdrawal. The scene was set for Slim to be able to deploy his superior mobility and firepower to destroy the main Japanese army in Burma.

By the end of the year, however, it became apparent that the Japanese were not going to conform to Slim’s plan for the battle, and General Kimura had seen the trap which his forces would be caught in if they attempted to stand and fight in the Shwebo Plain. Showing unusual flexibility and moral courage Kimura promptly withdrew his reconstituted 15th Army behind the Irrawaddy. Kimura hoped, not without reason, to be able to smash Slim’s army as it attempted to cross the river, which in itself presented an immense obstacle to the British. He would then counter-attack and destroy Slim as the British withdrew during the monsoon to the Chindwin.

Kimura’s move behind the Irrawaddy destroyed at a stroke Slim’s plan. Undaunted, and recognising the supreme importance of destroying Kimura’s army rather than taking ground for its own sake, Slim came up with another plan. In basic outline, his new plan (Operation Extended Capital) entailed crossing the Irrawaddy and fighting the decisive battle in February in the plain around Mandalay and the low hills around Meiktila, the key enemy air and supply base in Central Burma. Both the road and rail links between Mandalay and Rangoon ran through Meiktila. If Meiktila fell, the whole structure of the Japanese defence of Central Burma would collapse.

June 2, 2023

“Montgomery was a military talent; Slim was a military genius”

Dr. Robert Lyman is a known fan of Field Marshal Slim (as am I, for the record), not only for his brilliant military achievements, but also as a writer:

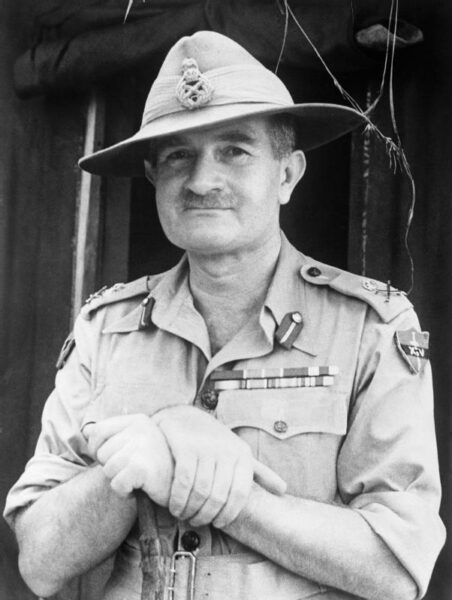

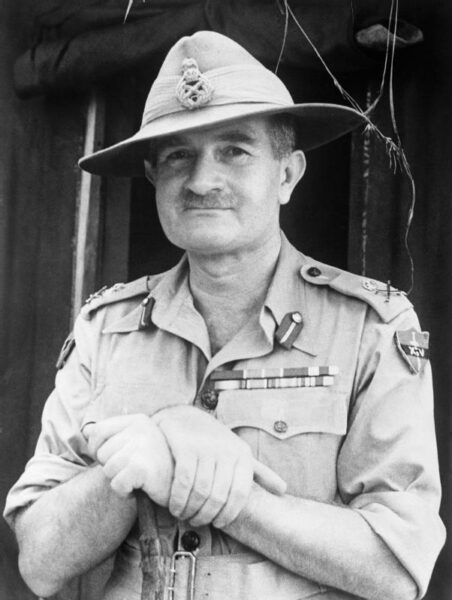

Field Marshal Sir William Slim (1891-1970), during his time as GOC XIVth Army.

Portrait by No. 9 Army Film & Photographic Unit via Wikimedia Commons.

How many British generals have been able to write as well as they could fight? Strangely perhaps, quite a few. Field Marshal Sir Michael Carver (Dilemmas of the Desert War, The Seven Ages of the British Army), General Sir David Fraser (And We Shall Shock Them), General Sir John Hackett (The Third World War) and Major General John Strawson (Beggars in Red) are four outstanding soldier-writers that spring immediately to mind. Even Monty wrote his memoirs. And in our own day I’ve read plenty of competent books from a slew of men who’ve reached the top of the profession of arms. The work of some, like that of General Sir Richard Sherriff (2017: War with Russia), Major General Mungo Melvin (Manstein) and Brigadier Allan Mallinson (Too Important for the Generals et al), could be described as outstanding. Julian Thompson and Richard Dannatt also fit this bill. But by far and away the best of Britain’s soldier-writers in the last century was also probably the greatest soldier – and field commander – of them all: Bill Slim. He was, more properly, Field Marshal William J. Slim KG, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, DSO, MC, KStJ, the onetime General Officer Commanding the famous 14th Army – the so-called Forgotten Army – of Burma fame. He was, in this author’s view, the greatest British general of the last war (to avoid further debate, let’s just agree that Monty failed as a coalition commander, whereas Slim excelled). Slim’s ability as a general is perfectly summed up by the historian Frank McLynn:

Slim’s encirclement of the Japanese on the Irrawaddy deserves to rank with the great military achievements of all time – Alexander at Gaugamela in 331 BC, Hannibal at Cannae (216 BC), Julius Caesar at Alesia (58 BC), the Mongol general Subudei at Mohi (1241) or Napoleon at Austerlitz (1805). The often made – but actually ludicrous – comparison between Montgomery and Slim is relevant here … there is no Montgomery equivalent of the Irrawaddy campaign … Montgomery was a military talent; Slim was a military genius.1

Some hint of Bill Slim’s fluency with the written word to complement his ability as a soldier came with the publication of Defeat into Victory in 1956, his superb retelling of the Burma story. Apart from its remarkable tale – the humiliation of British Arms in 1942 eventually overturned by a triumphant (and largely Indian) army in 1945 (87% of Slim’s army was Indian) – the quality of the writing was astonishing. Its author, a man who would be appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff in 1949 (following Monty), the first Sepoy General ever to do so, and by Attlee no less, could clearly wield a pen every bit as he could destroy Japanese armies in battle (a feat he achieved twice, first in 1944 and again in 1945). When the book was first published it was an instant publishing sensation with the first edition of 20,000 selling out immediately. The Field recorded: “Of all the world’s greatest records of war and military adventure, this story must surely take its place among the greatest. It is told with a wealth of human understanding, a gift of vivid description, and a revelation of the indomitable spirit of the fighting man that can seldom have been equalled – let alone surpassed – in military history.” The London Evening Standard was as effusive in its praise: “He has written the best general’s book of World War II. Nobody who reads his account of the war, meticulously honest yet deeply moving, will doubt that here is a soldier of stature and a man among men.” The author John Masters, who served in the 14th Army, wrote in the New York Times on 19 November 1961 that it was “a dramatic story with one principal character and several hundred subordinate characters”, arguing that Slim was “an expert soldier and an expert writer”. The book remains a best seller today.

The following year Slim also published an anthology of speeches and lectures, loosely based on the theme of leadership, called Courage and Other Broadcasts. Then in 1959 he published his second book, Unofficial History, which bears out in full Masters’ description of Slim as a superb writer. It was a deeply personal, honest though light hearted account of events during his service. It received widespread acclaim. The author John Connell described it as “for the most part uproarious fun. If Bill Slim hadn’t been a first-rate soldier, what a short story writer he might have made.” For its part, The National Review wrote: “One of the most significant aspects of Field Marshal Slim’s book is the affectionate respect he shows when he writes about British and Indian soldiers. He finds plenty to amuse him too. I doubt whether a kindlier or truer description of the contemporary soldier has been given anywhere than in Unofficial History … It is one of the most delightful and amusing books about modern campaigning I have ever read.”

1. The General Wondered Why https://amzn.eu/d/45gHfOH

April 28, 2023

Field Marshal Slim’s secret vice – he also wrote articles and short stories under pseudonym

It’s no secret that I have a very high regard for Field Marshal William Slim, so I’m quite looking forward to reading some of Slim’s pre-WW2 writings that have just been gathered together by Dr. Robert Lyman in a three-volume set:

Few people during his lifetime, and even fewer now, know that the man who was to become one of the greatest British generals of all time – and I’m not exaggerating – was in fact a secret scribbler. Now, many people know that he was the author of at least two best selling books. In 1956 he wrote his account of the Burma campaign, Defeat into Victory, described by one reviewer, quite rightly in my view, as “the best general’s book of World War II”. Then, in 1959, he published, under the title of Unofficial History, a series of articles about his military experience, some of which had been published previously as articles in Blackwood’s magazine. This was the first indication that there was an unknown literary side to Slim. The fact that he was a secret scribbler, or at least had been one once, was only publicly revealed on the publication of his biography in 1976 by Ronald Lewin – Slim, The Standard Bearer – which incidentally won the W.H. Smith Literary Award that same year. Lewin explained that Slim had written material for publication long before the war. In fact, between 1931 and 1940 he wrote a total of 44 articles, extending in length between two and eight thousand words – a total of 122,000 words in all – for a range of newspapers and magazines, including Blackwood’s Magazine, the Daily Mail, the Evening Express and the Illustrated Weekly of India. According to Lewin, he did this to supplement his earnings as an officer of the Indian Army. He didn’t do it to create a name for himself as a writer, or because he had pretensions to the artistic life, but because he needed the money. As with all other officers at the time who did not have the benefit of what was described euphemistically as “private means” he struggled to live off his army salary, especially to pay school fees for his children, John (born 1927) and Una (born 1930). Accordingly, he turned his hand to writing articles under a pseudonym, mainly of Anthony Mills (Mills being Slim spelt backwards) and, in one instance, that of Judy O’Grady.

With the war over, and senior military rank attained, he never again penned stories of this kind for publication. With it died any common remembrance of his pre-war literary activities. Copies of the articles have languished ever since amidst his papers in the Churchill Archives Centre at the University of Cambridge, from where I rescued them last year. They have been republished this week by Richard Foreman of Sharpe Books.

During the time Slim was writing these the pseudonym protected him from the gaze of those in the military who might believe that serious soldiers didn’t write fiction, and certainly not for public consumption via the newspapers. He certainly went to some lengths to ensure that his military friends and colleagues did not know of this unusual extra-curricular activity. In a letter to Mr S. Jepson, editor of the Illustrated Times of India on 26 July 1939 (he was then Commanding Officer of 2/7 Gurkha Rifles in Shillong, Assam) he warned that he needed to use an additional pseudonym to the one he normally used, because that – Anthony Mills – would then be immediately “known to several people and I do not wish them to identify me also as the writer of certain articles in Blackwood’s and Home newspapers. I am supposed to be a serious soldier and I’m afraid Anthony Mills isn’t.”

What do these 44 articles tell us of Slim? He would never have pretended that his writings represented any higher form of literary art. He certainly had no pretensions to a life as a writer. He was, first and foremost, a soldier. His writing was to supplement the family’s income. But, as readers will attest, he was very good at it. They demonstrate his supreme ability with words. As Defeat into Victory was to demonstrate, he was a master of the telling phrase every bit as much as he was a master of the battlefield. He made words work. They were used simply, sparingly, directly. Nothing was wasted; all achieved their purpose.

The articles also show Slim’s propensity for storytelling. Each story has a purpose. Some were simply to provide a picture of some of the characters in his Gurkha battalion, some to tell the story of a battle or of an incident while on military operations. Some are funny, some not. Some are of an entirely different kind, and have no military context whatsoever. These are often short adventure stories, while some can best be described as morality tales. A couple of them warned his readers not to jump to conclusions about a person’s character. Some showed a romantic tendency to his nature.

The stories can be placed into three broad categories. The first comprises seventeen stories about the Indian Army, of which the Gurkha regiments formed an important part. The second group are eleven stories about India, with no or only a passing military reference. The third, much smaller group, contains seventeen stories with no Indian or military dimension.

March 16, 2023

Field Marshal Slim’s one and only demotion … from lance-corporal back down to private

William Slim, arguably the best British general of the Second World War, didn’t have the fastest start to his military career, as recounted in an article by Frank Owen, the editor of the WW2 South East Asia theatre publication Phoenix. This and many others appear in Dr. Robert Lyman’s upcoming book Slim, Master of War:

The General stood on an ammunition box. Facing him in a green amphitheatre of the low hills that ring the Palel Plain, sat or squatted the British officers and sergeants of the 11th East African Division. They were then new to the Burma Front and were moving into the line the next day. The General removed his battered slouch hat, which the Gurkhas wear and which has become the headgear of the 14th Army. “Take a good look at my mug”, he advised. “Not that I consider it to be an oil painting. But I am the Army Commander and you had better be able to recognize me — if only to say “Look out, the old b…. is coming round”.

Lieutenant-General Sir William Slim, KCB, CB, DSO, MC (“Bill”) is 53, burly, grey and going a bit bald. His mug is large and weather beaten, with a broad nose, jutting jaw, and twinkling hazel eyes. He looks like a well-to-do West Country farmer, and could be one. For he has energy and patience and, above all, the man has common sense. However, so far Slim has not farmed. He started life as a junior clerk, once he was a school teacher, and then he became the foreman of a testing gang in a Midland engineering works. For the next 30 years Slim was a soldier.

He began at the bottom of the ladder as a Territorial private. August 4, 1914, found him at Summer camp with his regiment. The Territorials were at once embodied in the Regular Army, and Slim got his first stripe as lance-corporal. A few weeks later he was a private again, the only demotion that this Lieutenant-General has suffered.

It was a sweltering, dusty day and the regiment plodded on its twenty-mile route march down an endless Yorkshire lane. At that time British troops still marched in fours, so that Lance-Corporal Slim, as he swung along by the side of his men, made the fifth in the file, which brought him very close to the roadside. There were cottages there and an old lady stood at the garden gate.

“I can see her yet”, Slim reminisces. “she was a beautiful old lady with her hair neatly parted in the middle and wearing a black print dress. In her hand she held a beautiful jug, and on the top of that jug was a beautiful foam, indicating that it contained beer. She was offering it to the soldier boys.”

The Lance-Corporal took one pace to the side and grasped the jug. As he did, the column was halted with a roar. The Colonel, who rode a horse at its head, had glanced back. Slim was hailed before him and “busted” on the spot. The Colonel bellowed “Had we been in France you would have been shot.” Slim confides, “I thought he was a damned old fool – and he was. I lost my stripe, but he lost his army.” In truth he did, in France in March 1918. Bill soon got his stripe back.

Now in this corner of Palel Plain, one of India’s bloodiest battlefields and the scene of one of his greatest victories, Slim tells the officers and men of the 11th Division, “I have commanded every kind of formation from a section upwards to this army, which happens to be the largest single one in the world.” (At that time, Slim had under his command half a million troops.) “I tell you this simply that you shall realize I know what I am talking about. I understand the British soldier because I have been one, and I have learned about the Japanese soldier because I have been beaten by him. I have been kicked by this enemy in the place where it hurts, and all the way from Rangoon to India where I had to dust-off my pants. Now, gentlemen, we are kicking our Japanese neighbours back to Rangoon.”

Slim commanded the rear guard of the army that retreated from Burma in 1942. He is proud of that. His men marched and fought for a hundred days and nights and across a thousand miles. But this retreat was no Dunkirk. Says Slim “We brought our weapons out with us, and we carried our wounded, too. Dog-tired soldiers, hardly able to put one foot in front of another, would stagger along for hours carrying or holding up a wounded comrade. When at last they reached India over those terrible jungle mountains they did not go back to an island fortress and to their own people where they could rest and refit. The Army of Burma sank down on the frontier of India, dead beat and in rags. But, they fought here all through the downpour of the monsoon, and they saved India until a great new Army – which is this one – could be built up to take the offensive once again. In those days, if anyone had gone to me with a single piece of good news I would have burst out crying. Nobody ever did.”

He tells another story. One day he entered a jungle glade in a tank. In front of him stood a group of soldiers, in their midst the eternal Tommy. Assuming an optimism which he did not feel, Slim jumped out of the tank and approached them. “Gentlemen!” he said (which is the nice way that British generals sometimes address their troops) “Things might be worse!”

“‘Ow could they be worse?” inquired the Tommy.

“Well, it could rain” said Slim, lightly. He adds “And within quarter of an hour it did.”

March 13, 2023

Good “peacetime” generals versus good “wartime” generals

“Shady Maples“, a serving Canadian Army officer, explains why the skills and talents that allow an officer to rise to general rank in peacetime have no direct relationship with how that officer will perform in a shooting war:

Field Marshal Sir William Slim (1891-1970), during his time as GOC XIVth Army in Burma.

Portrait by No. 9 Army Film & Photographic Unit via Wikimedia Commons.

I am not the first person to make these kinds of observations. Jim Storr has written about peacetime promotion culture in the British Army and Thomas E. Ricks did the same with U.S. Army. Here is an excerpt from Storr:

It appears that many of those whom the British Army promoted in peacetime during the twentieth century were found wanting on the outbreak of war. Promotion to high command in peacetime very much reflects the values of existing senior commanders, themselves largely the products of a peacetime promotion system. To that extent it reflects deeply held values, and has an obvious impact on operational effectiveness in war.

Roughly two-thirds of those who commanded formations in the BEF [British Expeditionary Force] of 1940 were either sacked, retired immediately, or were never given another formation to command in the field.

Ricks describes a similar phenomenon occurring in the U.S. Army during the Second World War. Many senior leaders who had risen during peacetime couldn’t perform under real-world conditions. Under the stern hand of George C. Marshall, then Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, generals were removed from command at a rate that is unheard of today. Many of those who were fired had glowing records and some went on to redeem their reputations in later commands, which suggests that they had been promoted too soon or too high above their level of competence.

More recently, Russia has been churning through general officers in Ukraine, seemingly desperate to find someone who can achieve Putin’s war aims. If an army systematically promotes its officers above their level of competence in peacetime, then clearly their selection and assessment criteria are not aligned with the actual job requirements.

To illustrate the point, Storr compares careers of Second World War British Field Marshals. The first, Field Marshal John Verreker a.k.a. Lord Gort, was Commander-in-Chief (C.-in-C.) of the BEF during its disastrous efforts in France in 1940.

[Gort] was the epitome of the system: young, highly decorated, charismatic, promoted through and entirely within the system. He was only 51 when appointed CIGS [Chief of Imperial General Staff] … As C.-in-C. of the BEF, he “fussed over details and things of comparatively little consequence” and had a “constant preoccupation with things of small detail”.

After he oversaw the evacuation of British troops from Dunkirk, Gort was removed from command and served out the rest of the war in non-combatant posts. It should be noted that Gort was not a bad soldier. During the First World War, he rose from the rank of captain to acting lieutenant-colonel and in the process earned the Distinguished Service Order (with bar) and the Victoria Cross. It was during the interwar years that Gort ascended from the substantive rank of Major to Field Marshal. Battles may be won with good-enough tactics and a lot of chutzpah, but Gort was unprepared for the complexities of wartime command at the strategic level. He did, however, excel at playing politics.

For contrast, here is Storr’s description of Field Marshal William “Bill” Slim:

[The] 47-year-old Bill Slim was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in 1938, perhaps at the last possible opportunity. Slim had not been to Sandhurst; he had gained his commission “through the back door” and had come from a modest background. The outbreak of the Second World War saw him commanding a brigade in East Africa. Within four years he was commanding the Fourteenth Army in Burma … Slim was obviously not the product of a stable heirarchy in peacetime. His rise to fame came entirely during wartime. He was arguably one of the greatest British generals of the twentieth century. The contrast with Gort could not be more marked.

For his part, Ricks has a takes a wider view of how the post-war U.S. Army made some officers too big to fail:

Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq were all small, ambiguous, increasingly unpopular wars, and in each, success was harder to define than it was in World War II. Firing generals seemed to send a signal to the public that the war was going poorly.

But that is only a partial explanation. Changes in our broader society are also to blame. During the 1950s, the military, like much of the nation, became more “corporate” — less tolerant of the maverick and more likely to favor conformist “organization men”. As a large, bureaucratized national-security establishment developed to wage the Cold War, the nation’s generals also began acting less like stewards of a profession, responsible to the public at large, and more like members of a guild, looking out primarily for their own interests.

It seems like loyalty up became more important than loyalty out.

March 12, 2023

The young British officer’s attitude toward his men

Dr. Robert Lyman has been working on pulling together various newspaper and magazine articles written by Field Marshal William Slim before the Second World War, to be published later this year. I believe this will include everything he included (in shorter form in some cases) in his 1959 book Unofficial History plus many others. In this excerpt from “Private Richard Chuck, aka The Incorrigible Rogue”, Slim recounts taking command of a company of recent conscripts while recuperating from wounds received earlier in WW1:

“Light duty of a clerical nature,” announced the President of the Medical Board. Not too bad, I thought, as I struggled back into my shirt. “Light duty of a clerical nature” had a nice leisurely sound about it. I remembered a visit I had paid to a friend in one of the new government departments that were springing up all over London at the end of 1915. He had sat at a large desk dictating letters to an attractive young lady. When she got tired of taking down letters, she poured out tea for us. She did it very charmingly. Decidedly, light duty of a clerical nature might prove an agreeable change after a hectic year as a platoon commander and a rather grim six months in hospital. Alas, after a month in charge of the officers’ mess accounts of a reserve battalion, with no more assistant than an adenoidal “C” Class clerk, I had revised my opinion. My one idea was to escape from “light duty of a clerical nature” into something more active. Reserve battalions were like those reservoirs that haunted the arithmetic of our youth — the sort that were filled by two streams and emptied by one. Flowing in came the recovered men from hospitals and convalescent homes and the new enlistments; out went the drafts to battalions overseas. When the stream of voluntary recruits was reduced to a trickle the only way to restore the intake was by conscription, and this was my chance.

It had been decided to segregate the conscripts into a separate company as they arrived. I happened to be the senior subaltern at the moment and I applied for command of the new company. Rather to my surprise, for I was still nominally on light duty, I got it. The conscripts, about a hundred and twenty of them, duly arrived. They looked very much like any other civilians suddenly pushed into uniform, awkward, bewildered, and slightly sheepish, and I regarded them with some misgiving. After all, they were conscripts; I wondered if I should like them.

The young British officer commanding native troops is often asked if he likes his men. An absurd question, for there is only one answer. They are his men. Whether they are jet-black, brown, yellow, or café-au-lait, the young officer will tell you that his particular fellows possess a combination of military virtues denied to any other race. Good soldiers! He is prepared to back them against the Brigade of Guards itself! And not only does the young officer say this, but he most firmly believes it, and that is why, on a thousand battlefields, his men have justified his faith.

In a week I felt like that about my conscripts. I was a certain rise to any remark about one volunteer being worth three pressed men. Slackers? Not a bit of it! They all had good reasons for not joining up. How did I know? I would ask them. And I did. I had them, one by one, into the company office, without even an N.C.O. to see whether military etiquette was observed. They were quite frank. Most of them did have reasons — dependants who would suffer when they went, one-man businesses that would have to shut down. Underlying all the reasons of those who were husbands and fathers was the feeling that the young single men who had escaped into well-paid munitions jobs might have been combed out first.

[…]

We had now advanced far enough in our training to introduce the company to the mysteries of the Mills bomb. There is something about a bomb which is foreign to an Englishman’s nature. Some nations throw bombs as naturally as we kick footballs, but put a bomb into an unschooled Englishman’s hands and all his fingers become thumbs, an ague affects his limbs, and his wits desert him. If he does not fumble the beastly thing and drop it smoking at his — and your — feet, he will probably be so anxious to get rid of it that he will hurl it wildly into the shelter trench where his uneasy comrades cower for safety. It is therefore essential that the recruit should be led gently up to the nerve-racking ordeal of throwing his first live bomb; but as I demonstrated to squad after squad the bomb’s simple mechanism, I grew more and more tired with each until I could no longer resist the temptation to stage a little excitement. I fitted a dummy bomb, containing, of course, neither detonator nor explosive, with a live cap and fuse. Then for the twentieth time I began!

When you pull out the safety-pin you must keep your hand on the lever or it will fly off. If it does it will release the striker, which will hit the cap, which will set the fuse burning. Then in five seconds off goes your bomb. So when you pull out the pin don’t hold the bomb like this!’

I lifted my dummy, jerked out the pin, and let the lever fly off. There was a hiss, and a thin trail of smoke quavered upwards. For a second, until they realized its meaning, the squad blankly watched that tell-tale smoke. Then in a wild sauve qui peut they scattered, some into a nearby trench, others, too panic-stricken to remember this refuge, madly across country, I looked round, childishly pleased at my little joke, to find one figure still stolidly planted before me. Private Chuck alone held his ground, placidly regarding me, the smoking bomb, and his fleeing companions with equal nonchalance. This Casablanca act was, I felt, the final proof of mental deficiency — and yet the small eyes that for a moment met mine were perfectly sane and not a little amused.

“Well,” I said, rather piqued, “hy don’t you run with the others?” A slow grin passed over Chuck’s broad face.

“I reckon if it ‘ud been a real bomb you’d ‘ave got rid of it fast enough,” he said. Light dawned on me.

“After this, Chuck,” I answered, “you can give up pretending to be a fool; you won’t get your discharge that way!”

He looked at me rather startled, and then began to laugh. He laughed quietly, but his great shoulders shook, and when the squad came creeping back they found us both laughing. They found, too, although they may not have realized it at first, a new Chuck; not by any means the sergeant-major’s dream of a soldier, but one who accepted philosophically the irksome restrictions of army life and who even did a little more than the legal minimum.

November 19, 2022

Prelude to Victory: Burma, 1942

Army University Press

Published 11 Feb 2022In late 1941 and early 1942 the Imperial Japanese Army swept through the Asia-Pacific region like a wildfire. The Allies appeared powerless to stop them. With the British Army in Asia reeling, and pushed back to the frontier of India, something had to be done to stem the tide. “Prelude to Victory: Burma, 1942” provides context for Field Marshal William J. Slim and the 14th Army’s struggle to retake Burma from the Japanese.

March 21, 2021

Crap Tactics in the Pacific – Shall MacArthur Return? – WW2 – 134 – March 20, 1942

World War Two

Published 20 Mar 2021MacArthur makes one of the most iconic remarks of the whole war, but considering the fact that the Philippines seem unsalvageable, it’s pretty unclear just how he’ll do it, especially since even though ever more American soldiers are arriving in Australia, the Japanese threat to Australia grows daily. Bill Slim arrives in Burma to take command of I Burma Corps, and Joe Stilwell has taken over two Chinese Nationalist armies, so the defense of Burma looks like it might go on a while longer, though the Allies are at a serious disadvantage after losing Rangoon. The Japanese, for their part, are trying to figure out how the heck they’re going to administer all the territory they’ve taken this year and bring natural resources to Japan itself. There is still scattered fighting in the USSR, but the spring muds have put pad to any major offensives for the time being. As for the British, they launch Operation Outward, a hydrogen balloon campaign over Germany. Yep, you read that right. What a week.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @ww2_day_by_day – https://www.instagram.com/ww2_day_by_day

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesWritten and Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Maria Kyhle

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell

Edited by: Iryna Dulka

Sound design: Marek Kamiński

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Colorizations by:

– Mikołaj Uchman

– Daniel Weiss

– Norman Stewart – https://oldtimesincolor.blogspot.com/

– Adrien Fillon – https://www.instagram.com/adrien.colo…

– Olga Shirnina, a.k.a. Klimbim – https://klimbim2014.wordpress.com/Soundtracks from the Epidemic Sound:

– Rannar Sillard – “Easy Target”

– Jo Wandrini – “Dragon King”

– Wendel Scherer – “Time to Face Them”

– Howard Harper-Barnes – “London”

– Philip Ayers – “The Unexplored”

– Farrell Wooten – “Duels”

– Johan Hynynen – “Dark Beginning”

– Craft Case – “Secret Cargo”

– Johannes Bornlöf – “The Inspector 4”Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

June 21, 2020

Burma Victory (1945)

PeriscopeFilm

Published 31 May 2016Support Our Channel: https://www.patreon.com/PeriscopeFilm

Made in 1945, BURMA VICTORY is a British documentary about the Burma Campaign during World War Two. It was directed by Roy Boulting. The introduction to the film outlines the geography and climate of Burma, and the extent of the Japanese conquests. The film then describes the establishment of the South East Asian Command (SEAC) under Mountbatten, “a born innovator and firm believer in the unorthodox”, and gives a comparatively detailed account of subsequent military events, including the Battle of Imphal-Kohima and Slim’s drive on Mandalay, Arakan landings, the northern offensive of the Americans and Chinese under Stilwell, and the roles played by Chindits and Merrill’s Marauders. The film ends with the capture of Rangoon and the Japanese surrender. The film focuses on the difficulties of climate, terrain, the endemic diseases of dysentery, malaria, etc., the vital role of air supplies, the shattering of the myth of Japanese invincibility and the secondary role of the Burma campaign in overall Allied strategy.

This film represents a British look at the campaign and was the pet project of Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander, South-East Asia, and he planned it as a joint Anglo-American production. But this scheme foundered over the inability of the U.S. leadership and British to agree on the main theme of the film. The British wanted it to concentrate on the drive southwards to liberate Burma. The Americans, anxious not to be seen to be participating in the restoration of the British Empire, wanted to emphasize the heroic building of the Ledo Road and the drive northwards to relieve the Chinese. In the end the two sides went their separate ways. The Americans produced the Ronald Reagan narrated film The Stilwell Road and the British made Burma Victory. It was the final production of the Army Film and Photographic Unit (AFPU) and was directed, like Desert Victory (1943), by Roy Boulting. Not released until after the war was over, it was hailed and promoted as “the real Burma film”.

The Burma Campaign in the South-East Asian theatre of World War II was fought primarily between the forces of the British Empire and China, with support from the United States, against the forces of the Empire of Japan, Thailand, and the Indian National Army. British Empire forces peaked at around 1,000,000 land, naval and air forces, and were drawn primarily from British India, with British Army forces (equivalent to 8 regular infantry divisions and 6 tank regiments), 100,000 East and West African colonial troops, and smaller numbers of land and air forces from several other Dominions and Colonies. The Burmese Independence Army was trained by the Japanese and spearheaded the initial attacks against British Empire forces.

The campaign had a number of notable features. The geographical characteristics of the region meant that factors like weather, disease and terrain had a major effect on operations. The lack of transport infrastructure placed an emphasis on military engineering and air transport to move and supply troops, and evacuate wounded. The campaign was also politically complex, with the British, the United States and the Chinese all having different strategic priorities.

South East Asia Command (SEAC) was the body set up to be in overall charge of Allied operations in the South-East Asian Theatre during World War II. Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten served as Supreme Allied Commander of the South East Asia Command from October 1943 through the disbandment of SEAC in 1946.

This film is part of the Periscope Film LLC archive, one of the largest historic military, transportation, and aviation stock footage collections in the USA. Entirely film backed, this material is available for licensing in 24p HD and 2k. For more information visit http://www.PeriscopeFilm.com

February 18, 2019

Forgotten history of India’s Thermopylae

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published on 20 Jun 2017The History Guy tells the forgotten history of the World War II battle of Imphal also known as India’s Thermopylae.

The History Guy uses images that are in the Public Domain. As photographs of actual events are often not available, I will sometimes use photographs of similar events or objects for illustration.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TheHistoryGuy

The History Guy: Five Minutes of History is the place to find short snippets of forgotten history from five to fifteen minutes long. If you like history too, this is the channel for you.

The episode is intended for educational purposes. All events are presented in historical context.

October 19, 2013

QotD: Army leadership

Long ago I had learned that in conversation with an irate senior, a junior officer should confine himself strictly to the three remarks, “Yes, sir”, “No, sir”, and “Sorry, sir”! Repeated in the proper sequence, they will get him through the most difficult interview with the minimum discomfiture.

Field Marshal William Slim, “Student’s Interlude”, Unofficial History, 1959.

October 13, 2013

QotD: Luck of the draw

When the time came for us to leave Persia and make the long trek back to Iraq, we stopped again for a few days with Robertson in Kermanshah. Then I said good-bye to my host, my Persian friends, and to his house with keen regret — with, as a matter of fact, a secret personal regret.

As a junior officer in the first World War, I had been presumptuous enough sometimes to hope that if I survived and were not found out, I might with tremendous luck, by the time the next great war arrived, be a general. Then, I fondly imagined my headquarters would move from château to château, from which I would occasionally emerge, fortified by good wine and French cooking, to wish the troops the best of luck in their next attack. Alas, when the time did come and, by good fortune in the game of military snakes and ladders, I found myself a general, I was so inept in my choice of theatres that no châteaux were available. More often than not, I had to make do with a plot of desert sand, a tree in the African bush, or a patch of jungle, while my cuisine was based on bully beef and the vintages of my imagination were replaced by over-chlorinated water. Once or twice, however, I did get, if not my château with its chef and its cellar, at least an excellent substitute — an oil company bungalow. Once having sampled its comfort I would not have swapped Robertson’s house for all the châteaux of the Loire. Dug in there, a delectable future had spread before me in which I achieved my youthful ambition and conducted the war from linen-sheeted bed and luxurious long bath. But, like other youthful hopes, the vision faded. I was once more, had I known it, destined to châteaux-less wilderness.

Field Marshal William Slim, “Persian Pattern”, Unofficial History, 1959.

September 13, 2013

QotD: The constant theme of British battles through history

I have a theory that, while the battles the British fight may differ in the widest possible way, they have invariably two common characteristics — they are always fought uphill and always at the junction of two or more map sheets.

Field Marshal William Slim, “Aid to the Civil”, Unoficial History, 1959.