toldinstone

Published 25 Feb 2026How Sparta, the most powerful Greek city-state, collapsed in only 20 years.

0:00 Introduction

0:38 Classical Sparta

1:29 Spartan politics

2:22 Helots

3:24 Population decline

4:37 Hubris

5:25 The Battle of Leuctra

6:42 Messenia liberated

7:35 Enter Macedon

8:08 Attempts at reform

9:08 Irrelevance

9:37 Roman Sparta

(more…)

February 26, 2026

The Decline and Fall of Sparta

February 25, 2026

QotD: The notion of “history”

“History” is itself a fairly recent phenomenon, historically speaking. As far as we can tell, all the preliterate civilizations, and a lot of the literate ones, lived in what amounted to an endless now. I find [Julian] Jaynes’s ideas [in his book The Origins of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind] very helpful in this regard, but we don’t need him for this, because whatever the explanation, it’s an obvious fact of historiography (“the history of History”; the study of the writing of History). Herodotus and Thucydides were more or less contemporaries, but what a difference in their work! Herodotus’s “history” was a collection of anecdotes; Thucydides focused on people and their motivations; but both of them wrote in the 400s BC — that is, 2500 years ago.

We are closer in time to them than they were to the men who built the Pyramids — by a long shot — and think about that for a second. That’s the vast scope of merely literate human history. Human settlement itself goes back at least another 6,000 years before that, and probably a lot longer.

So far as we can tell, well into historical time men had no real conception of “the past”. Even those men who had recently died weren’t really gone, and again I find Jaynes useful here, but he’s not necessary; it’s obvious by funeral customs alone. They had a basic notion of change, but it was by definition cyclical — the sun rises and sets, the moon goes through its phases, the stars move, the seasons change, but always in an ordered procession. What once was will always return; what is will pass away, but always to return again.

Linear time — the sense of time as a stream, rather than a cycle; the idea that the “past” forecloses possibilities that will never return — only shows up comparatively late in literate history. Hesiod wrote somewhere between 750 and 650 BC; his was the first work to describe a Golden Age as something that might’ve actually existed (as opposed to the Flood narratives of the ancient Middle East).

Note that this is not yet History — that would have to wait another 300 years or so. Whereas a Thucydides could say, with every freshman that has ever taken a history class, that “We study the past so that we don’t make the same mistakes”, that would’ve been meaningless to Hesiod — we can’t imitate the men of the Golden Age, because they were a different species of man.

Note also that Thucydides could say “Don’t make the mistakes of the past” because “the past” he was describing was “the past” of currently living men — he was himself a participant in the events he was describing “historically”.

The notion that the Golden Age could return, or a new era begin, within the lifetime of a living man is newer still. That’s the eschaton proper, and for our purposes it’s explicitly Christian — that is, it’s at most 2000 years old. Christ explicitly promised that some of the men in the crowd at his execution would live to see the end of the world (hence the fun medieval tradition of the Wandering Jew). And since that didn’t happen, you get the old-school, capital-G Gnostics, who interpreted that failure to mean that it was up to us to bring about our own salvation via secret knowledge …

… or, in Europe starting about 1000 AD, you get the notion that it’s up to us to somehow force Jesus to return by killing off all the sinners. I can’t recommend enough Norman Cohn’s classic study The Pursuit of the Millennium if you want the gory details. Cohn served with the American forces denazifying Europe, so he has some interesting speculations along Vogelin’s lines, but for our purposes it doesn’t matter. All we need to do is note that this was in many ways The Last Idea.

Severian, “The Ghosts”, Founding Questions, 2022-05-17.

February 11, 2026

QotD: Delusional takes – “There are no white people in the Bible”

[Responding to an image posted here.]

Oh boy, I get to post more Damned Facts that will offend people who richly deserve to be offended.

There were lots of white people in the Bible. And you don’t need to get into any definitional questions about the genetics of ancient Judea, either.

Greeks and Romans were white — that is, pale-skinned Caucasians. We know this from art, from sequenced genomes, and from contemporary descriptions of what they looked like. Herodotus described the Pontic Greeks as being blonde and blue-eyed.

Here’s the really Damned Fact: brownness in Mediterranean European populations was a late development. Post-Classical. Caused by …

… the Islamic invasions, post 722 CE. Resulted in Europeans of the Mediterranean coast becoming admixed (to put it very, very diplomatically) with Arabs and Africans. That’s why there’s a really noticeable gradient in Italy between lighter-skinned Northerners and darker-skinned Southerners; it’s all about how long various regions were under Islamic domination.

The question that usually comes up is, was Jesus himself “white”?

It’s possible. We can’t go by the artistic evidence, because Byzantine art deliberately confused Jesus with stylized depictions of the Emperor in his glory (there’s a really famous example of this in the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople). And those Greek emperors may well have been depicted as a bit blonder and more blue-eyed than they actually were, because that was considered beautiful. Dashboard Jesus is a late polyp of this tradition.

But until we find actual genetic material we’re not going to know. Imperial-run Palestine was a swirling cauldron of different ethnic groups, and the genetic boundaries didn’t necessarily match up neatly with the religious ones. Knowing that his parents were part of the Jewish people doesn’t necessarily help much.

The two most likely cases are that Jesus looked like a current-day city Arab, or he looked like a Philistine — that is, Greek with some local admixture; a lot of coastal Lebanese still look like that today. But full-bore pasty-skinned Euro can’t be ruled out.

ESR, The social media site formerly known as Twitter, 2025-11-10.

February 1, 2026

The Agora of Athens | A Historical Tour

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published 3 Oct 2025The Agora was the political and economic heart of ancient Athens. This tour explores its long history and evocative ruins.

Chapters

0:00 Introduction

0:47 Bouleuterion

1:44 Tholos

2:22 Monument of the Eponymous Heroes

2:56 Temple of Hephaestus

5:28 The Hellenistic Agora

6:16 Stoa of Attalos

6:57 Augustus and the Agora

8:06 Odeon of Agrippa

9:26 Herulian Wall

10:56 Overview

January 19, 2026

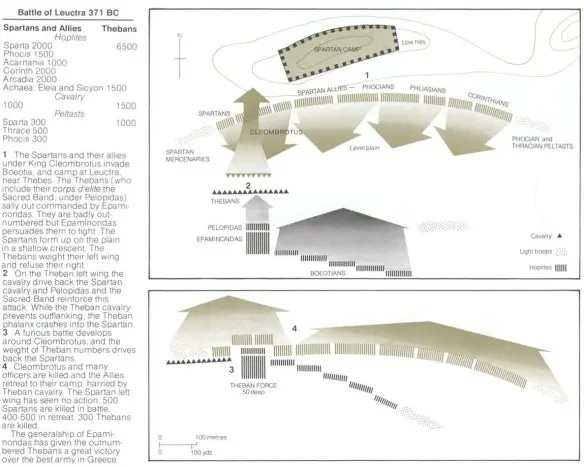

QotD: Epaminondas and the defeat of Sparta at Leuctra

In 371 BCE, the Theban General Epaminondas did battle with Sparta at the height of its power. Sparta, having won the Peloponnesian War 33 years earlier, dominated Southern Greece and carried an invincible reputation. They were unstoppable, and they were coming. Thebes and the rest of the Boeotian city-states, led by Epaminondas, needed a way to fight back.

Epaminondas led a smaller force (some 6,000 to Sparta’s 11,000, though historians debate the exact numbers) to a field in front of a Boeotian village called Leuctra. The Battle of Leuctra would not only mark the beginning of centuries of Spartan decline, but also change the way Greek armies battled all the way through the conquests of Alexander the Great.

How did Epaminondas do it? How could he upend the mighty Spartan empire with a force barely half the size? The answer lay in resource allocation, patience, and 300 extremely important gay men.

If you had the misfortune of fighting against a Spartan army in the last few centuries BCE, you had to contend with a phalanx of hoplites. Thousands of men would align shoulder to shoulder, stick out their shields and spears, and push. You probably had a phalanx of your own, but against the Spartan line, you stood no chance.

Epaminondas didn’t have the numbers to directly contend with the Spartan phalanx, but he did have a specific elite force: the Sacred Band of Thebes. The Sacred Band was made of 300 hand-picked warriors paired off into homosexual couples. The idea was that lovers would fight more fiercely for each other.

Instead of a futile effort to out-push a force half their size, the Boeotians overloaded one side. They put a majority of their force on the left side, thinning out the right. They advanced this overloaded left wing before the weaker right wing, hoping to win before the Spartans could fully engage.

The Boeotian left wing, led in part by the Sacred Band, broke through the Spartan line. With enemy forces charging the side and rear, the Spartans quickly routed. When the dust settled, Epaminondas inflicted upon the Spartans one of the most decisive blowouts in Greek history.

Diagram courtesy of WarHistory.org

Over 1,000 Spartans perished in the Battle of Leuctra, including their king and military leader Cleombrotus. The Boetians lost around a hundred, but exact estimates are hard to come by. By anyone’s estimate, their casualties paled in comparison. Sparta’s military reputation would never recover, and the next 200 years marked an era of Spartan decline.

Epaminondas didn’t invent the phalanx. In fact, it’s unclear who really did. There is evidence of a similar strategy in Sumer over 2,000 years earlier. It’s a fairly basic idea — everyone hold your shields together and push. But Epaminondas did advance the strategy. Others would continue to innovate on Epaminondas’ “oblique” advance, up to and including Alexander the Great.

Luke Brown, “Pushing Tush Is Ancient Technology”, Wide Left, 2025-10-13.

January 11, 2026

QotD: The limits of foreign policy realism

Longtime readers will remember that we’ve actually already talked about “realism” as a school of international relations study before, in the context of our discussion of Europa Universalis. But let’s briefly start out with what we mean when we say IR realism (properly “neo-realism” in its modern form): this is not simply being “realistic” about international politics. “Realism” is amazing branding, but “realists” are not simply claiming that they are observing reality – they have a broader claim about how reality works.

Instead realism is the view that international politics is fundamentally structured by the fact that states seek to maximize their power, act more or less rationally to do so, and are unrestrained by customs or international law. Thus the classic Thucydidean formulation in its most simple terms, “the strong do what they will, the weak suffer what they must”,1 with the additional proviso that, this being the case, all states seek to be as strong as possible.

If you accept those premises, you can chart a fairly consistent analytical vision of interstate activity basically from first principles, describing all sorts of behavior – balancing, coercion, hegemony and so on – that ought to occur in such systems and which does occur in the real world. Naturally, theory being what it is, neo-realist theory (which is what we call the modern post-1979 version of this thinking) is split into its own sub-schools based on exactly how they imagine this all works out, with defensive realism (“states aim to survive”) and offensive realism (“states aim to maximize power”), but we needn’t get into the details.

So when someone says they are a “foreign policy realist”, assuming they know what they’re talking about, they’re not saying they have a realistic vision of international politics, but that they instead believe that the actions of states are governed mostly by the pursuit of power and security, which they pursue mostly rationally, without moral, customary or legal constraint. This is, I must stress, not the only theory of the case (and we’ll get into some limits in a second).

The first problem with IR Realists is that they run into a contradiction between realism as an analytical tool and realism as a set of normative behaviors. Put another way, IR realism runs the risk of conflating “states generally act this way”, with “states should generally act this way”. You can see that specific contradiction manifested grotesquely in John Mearsheimer’s career as of late, where his principle argument is that because a realist perspective suggests that Russia would attack Ukraine that Russia was right to do so and therefore, somehow, the United States should not contest this (despite it being in the United States’ power-maximizing interest to do so). Note the jump from the analytical statement (“Russia was always likely to do this”) to the normative statement (“Russia carries no guilt, this is NATO’s fault, we should not stop this”). The former, of course, can always be true without the latter being necessary.

I should note, this sort of “normative smuggling” in realism is not remotely new: it is exactly how the very first instances of realist political thought are framed. The first expressions of IR realism are in Thucydides, where the Athenians – first at Corinth and then at Melos – make realist arguments expressly to get other states to do something, namely to acquiesce to Athenian Empire. The arguments in both cases are explicitly normative, that Athens did not act “contrary to the common practice of mankind” (expressed in realist dog-eat-dog terms) and so in the first case shouldn’t be punished with war by Sparta and in the latter case, that the Melians should submit to Athenian rule. In both cases, the Athenians are smuggling in a normative statement about what a state should do (in the former case, seemingly against interest!) into a description of what states supposedly always do.

I should note that one of my persistent complaints against international relations study in political science in general is that political scientists often read Thucydides very shallowly, dipping in for the theory and out for the rest. But Thucydides’ reader would not have missed that it is always the Athenians who make the realist arguments and they lost both the arguments [AND] the war. When Thucydides has the Melians caution that the Athenians’ “realist” ruthlessness would mean “your fall would be a signal for the heaviest vengeance and an example for the world to meditate upon”2 the ancient Greek reader knows they are right, in a way that it often seems to me political science students seem to miss.

And there’s a logical contradiction inherent in this sort of normative smuggling, which is that the smuggling is even necessary at all. After all, if states are mostly rational and largely pursue their own interests, loudly insisting that they should do so seems a bit pointless, doesn’t it? Using realism as a way to describe the world or to predict the actions of other states is consistent with the logical system, but using it to persuade other states – or your own state – seems to defeat the purpose. If you believe realism is true, your state and every other is going to act to maximize its power, regardless of what you do or say. If they can do otherwise than there must be some significant space for institutions, customs, morals, norms or simple mistakes and suddenly the air-tight logical framework of realism begins to break down.

That latter vision gives rise to constructivism (“international relations are shaped by ideology and culture”) and IR liberalism (“international relations are also shaped by institutions, which can bend the system away from the endless conflict realism anticipates”). The great irony of realism is that to think that having more realists in power would cause a country to behave in a more realist way is inconsistent with neo-Realism which would suggest countries ought to behave in realist ways even in the absence of realist theory or thinkers.

In practice – and this is the punchline – in my experience most “realists”, intentionally or not, use realism as a cover for strong ideological convictions, typically convictions which are uncomfortable to utter in the highly educated spaces that foreign policy chatter tends to happen. Sometimes those convictions are fairly benign – it is not an accident that there’s a vocal subset of IR-realists with ties to the CATO Institute, for instance. They’re libertarians who think the foreign policy adventures that often flew under the banner of constructivist or liberal internationalist label – that’s where you’d find “spreading democracy will make the world more peaceful” – were really expensive and they really dislike taxes. But “we should just spend a lot less on foreign policy” is a tough sell in the foreign policy space; realism can provide a more intellectually sophisticated gloss to the idea. Sometimes those convictions are less benign; one can’t help but notice the realist pretensions of some figures in the orbit of the current administration have a whiff of authoritarianism or ethnocentrism in them, since a realist framework can be used to drain imperial exploitation and butchery of its moral component, rendering it “just states maximizing their power – and better to be exploiter than exploited”.

One question I find useful to ask of any foreign policy framework, but especially of self-claimed realist frameworks is, “what compromise, what tradeoff does this demand of you?” Strategy, after all, is the art of priorities and that means accepting some things you want are lower priority; in the case of realism which holds that states seek to maximize power, it may mean assigning a high priority to things you do not want the state to do at all but which maximize its power. A realism deserving of the name, in applied practice would be endlessly caveated: “I hate, this but …” “I don’t like this, but …” “I would want to do this, but …” If a neo-realist analysis leads only to comfortable conclusions that someone and their priorities were right everywhere all along, it is simply ideology, wearing realism as a mask. And that is, to be frank, the most common form, as far as I can tell.

That isn’t to say there is nothing to neo-realism or foreign policy realists. I think as an analytical and predict tool, realism is quite valuable. States very often do behave in the way realist theory would suggest they ought, they just don’t always do so and it turns out norms and expectations matter a lot. Not the least of which because, as we’ve noted before, the economic model on which realist and neo-realist thinking was predicted basically no longer exists. To return to the current Ukraine War: is Putin really behaving rationally in a power-maximizing mode by putting his army to the torch capturing burned out Ukrainian farmland one centimeter at a time and no faster? It sure seems like Russian power has been reduced rather than enhanced by this move, even though realists will insist that Russia’s effort to dominate states near it is rational power-maximizing under offensive realism.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, June 27, 2025 (On the Limits of Realism)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2025-06-27.

- Thuc. 5.89.

- Thuc. 5.90.

January 3, 2026

Penelope vs Clytemnestra in Greek Mythology

MoAn Inc.

Published 10 Sept 2025I’m trying out shorter videos on the channel, so this is a very basic breakdown explanation. Clytemnestra and Penelope are polar opposites, and their characters bookend The Odyssey. One is seen as the best wife, one is seen as the worst. They’re supposed to be compared and contrasted in this way: Agamemnon’s homecoming to Mycenae is a warning to Odysseus about what could potentially go very, very wrong with his own return to Ithaca. There are so many fascinating ways to dissect these two women, so please don’t take this as a be-all-end-all!

Voice of Erica Stevenson, host of MoAn Inc.

(more…)

December 29, 2025

What Do We ACTUALLY Know About Homer? (Author of Iliad & Odyssey)

MoAn Inc.

Published 23 Dec 2025

(more…)

December 15, 2025

How to Eat Like an Ancient Stoic

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 8 Jul 2025Lentil soup with leeks, coriander seeds, and herbs

City/Region: Greece | Rome

Time Period: 3rd Century B.C.E. | 1st CenturyThe ancient stoics were all about being happy with what you’ve got. If one could learn to take pleasure in eating simple foods like lentil soup and barley bread (usually eaten by the poorest members of society), then they would have more happiness than if they constantly craved luxurious food. Granted, most of these philosophers were wealthy, so they didn’t actually have to live like the very poor.

The ancient Greek stoic philosopher Zeno of Citium was known for carrying around lentil soup in a clay pot, and that was probably just lentils boiled in water. This recipe, adapted from ancient Rome’s Apicius from a few centuries later, is a little fancier, but still rather simple and uses ingredients that would have been available to Zeno. Despite its simplicity, it’s surprisingly delicious with a hint of sweetness, oniony leek, and the cooling effect of the mint.

Boil the lentils; when skimmed, put in leeks and green cilantro. Pound coriander-seed, pennyroyal, silphium, mint, and rue, moisten with vinegar, add honey, blend with garum, vinegar, and defrutum. Pour over the lentils, add oil, serve.

— Apicius, de re coquinaria, 1st Century

December 12, 2025

Starships and Walls : Which Shall We Build?

Feral Historian

Published 25 Jul 2025While faster than light travel may be impossible, proclaiming absolutes based on the understanding of a particular time has a spotty record. But even if we are limited to sublight travel by the fundamental nature of the universe, we as a civilization have several macro-level choices to make, one of the most significant being which foundational concept do we want to build a future on: Ships? Or walls?

00:00 Intro

01:50 The Athenian Sailor

05:25 Frontiers

06:00 Assuming it’s Impossible

07:26 Picard Without Starfleet?

09:40 Culture over Economics

15:28 Founders of Worlds🔹 Patreon | patreon.com/FeralHistorian

🔹 Ko-Fi | ko-fi.com/feralhistorian

December 1, 2025

QotD: Young Cyrus, before he became “the Great”

Of all Cyrus’s many qualities: willpower, strength, charisma, glibness, intelligence, handsomeness; Xenophon makes a point of emphasizing one in particular, and his choice might strike some readers as strange. It is this: “He did not run from being defeated into the refuge of not doing that in which he had been defeated”. Cyrus learned to love the feeling of failure, because failure means you’re facing a worthy challenge, failure means you haven’t set your sights too low, failure means you’ve encountered a stone hard enough to sharpen your own edge. Yes, it’s the exact opposite of the curse of the child prodigy, and it’s the key to Cyrus’s success. He doesn’t flee failure, he seeks it out, hungers for it, rushes towards it again and again, becoming a little scarier every time. He’s found a cognitive meta-tool, one of those secrets of the universe which, if you can actually internalize them, make you better at everything. Failure feels good to him rather than bad, is it any surprise he goes on to conquer the world?

And then … the most important single moment in Cyrus’s education, the moment when it becomes clear that he has actually set his sights appropriately high. He gets bored of the hunts. Cyrus deduces, correctly, that the hunts he is sent on, and all the other little missions, are contrived. Each is a problem designed to impart a lesson, a little puzzle box constructed by a demiurge with a solution in mind. In this respect, they’re like the problems in your math textbook. And like the problems in your math textbook, getting good at them is very dangerous, because it can mislead and delude you into thinking that you’ve gotten good at math, when actually you’ve gotten good at the sorts of problems that people put in textbooks.

When you’re taught from textbooks, you quickly learn a set of false lessons that are very useful for completing homework assignments but very bad in the real world. For example: all problems in textbooks are solvable, all problems in textbooks are worth solving (if you care about your grade), all problems in textbooks are solvable by yourself, and all of the problems are solvable using the techniques in the chapter you just read. But in the real world, the most important skills are not solving a quadratic by completing the square or whatever, the most important skills are: recognizing whether it’s possible to solve a given problem, recognizing whether solving it is worthwhile, figuring out who can help you with the task, and figuring out which tools can be brought to bear on it. The all-important meta-skills are not only left undeveloped by textbook problems, they’re actively sabotaged and undermined. This is why so many people who got straight As in school never amount to anything.

The section covering his childhood and education concludes with a dialogue between Cyrus and his father Astyages as the two ride together towards the border of Persia. Astyages recapitulates and summarizes all of the lessons that Cyrus has been taught, and adds one extra super-secret leadership tip. Cyrus wants to know how to attract followers and keep their loyalty, and his father gives him a very good answer which is: just be great. Be the best at what you do. Be phenomenally effective at everything. People aren’t stupid, they want to follow a winner, so be the kind of guy who’s going to win over and over again, and if you aren’t that guy, then maybe choose a different career.

Cyrus asks and so Astyages clarifies: no, he doesn’t mean be great at making speeches, or at crafting an image, or at appearing to be very good at things. He doesn’t mean attending “leadership seminars”, or getting an MBA, or joining a networking organization for “young leaders”. He means getting extremely good at the actual, workaday, object-level tasks of your trade: “There is no shorter road, son … to seeming to be prudent about such things … than becoming prudent about them”. In Cyrus’s case, this means tactics, logistics, personnel selection, drill, all the unglamorous parts of running an ancient army. People aren’t stupid. If they see that he is great at these things, they will flock to his banner. And then, one more ingredient, the final step: make it clear that you care about their welfare. “The road to it is the same as that one should take if he desires to be loved by his friends, for I think one must be evident doing good for them.”

There you have it. Two simple #lifehacks to winning undying loyalty: be the best in the world at what you do, and actually give a damn about the people under you. Our rulers could learn a thing or two from this book. So ends the education.1 The rest of this book, and the bulk of it, is Cyrus putting these lessons into practice by very rapidly conquering all of the Ancient Near East. It’s telegraphed well in advance that the final boss of this conquest will be the mighty Neo-Babylonian empire founded by Nebuchadnezzar,2 but before he takes them on Cyrus first has to grind levels by putting down an incipient rebellion by his grandfather’s Armenian vassals,3 then whipping the neighboring Chaldeans into line, then peeling away the allegiance of various Assyrian nobles, then defeating the Babylonians’ Greek allies and Egyptian mercenaries, before finally taking on the Great King in his Great City.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: The Education of Cyrus, by Xenophon”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2024-01-08.

- There’s actually one other noteworthy bit of advice that Astyages gives:

“Above all else, remember for me never to delay providing provisions until need compels you; but when you are especially well off, then contrive before you are at a loss, for you will get more from whomever you ask if you do not seem to be in difficulty … be assured that you will be able to speak more persuasive words at just the moment when you are especially able to show that you are competent to do both good and harm.”

This is decent enough advice, but what makes it especially fun is that Astyages also applies it to the gods! Maybe it’s his own pagan spin on “God helps those who help themselves”, but Cyrus takes this advice and takes it a step further. He learns to interpret auguries himself so that he will never be at the mercy of priests. Then when he needs an omen, he performs the sacrifices, decides which of the entrails, the weather, the stars, and so on are pointing his way, loudly points them out, and ignores the rest.

Henrich notes in The Secret of our Success that divination can be an effective randomization strategy in certain sorts of game theoretic contests. But the true superpower is deciding on a case-by-case basis whether you’re going to act randomly, or just make everybody think you’re acting randomly.

- Yes, that Nebuchadnezzar.

- Somewhere in the middle of In Xanadu, Dalrymple recounts an old Arab proverb that goes: “Trust a snake before a Jew, and a Jew before a Greek. But never trust an Armenian.” The tricksy Armenian ruler more than lives up to this reputation. But when Cyrus outwits and captures him, his son shows up to beg for his life, and what follows is one of the more philosophically charged exchanges in the entire book. They go multiple rounds, but by the end of it the Armenian crown prince has put Cyrus in a logical box as deftly as Socrates ever did to one of his interlocutors, and Cyrus lets the king off with a warning. The prince goes on to combat anti-Armenian stereotypes by serving Cyrus faithfully to the end of his days.

November 8, 2025

History Summarized: Greece… TWO (it’s in Italy)

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 4 Jul 2025From the Olympians who brought you “Greece” and “The Other Side of Greece” comes the bold, innovative, and way shinier “GREECE TWO”.

SOURCES & Further Reading:

The Greeks: A Global History by Roderick Beaton

Ancient Greece: The Definitive Visual History produced by DK & Smithsonian

The Complete Greek Temples by Tony Spawforth

Ancient Cities Brought To Life by Jean-Claude Golvin

“From Sicily to Syria – The Growth of Trade and Colonization” from Ancient Greek Civilization by Jeremy McInerney

“Magna Graecia: Taras and Syracuse” and “Cyrene, Leptis Magna, and Ancient Libya” from Great Tours: Ancient Cities of the Mediterranean by Darius Arya

Sicily: An Island at the Crossroads of History by John Julius Norwich

“The Greeks: An Illustrated History” by Diane Harris Cline for National Geographic

November 3, 2025

QotD: Was Alexander “the Great”?

Finally, I think we need to talk briefly about Alexander’s character and his immediate impact in all of this. As I noted above, Alexander was charismatic and even witty and so there are a number of very famous anecdotes of him doing high-minded things: his treatment of Darius’ royal household, his treatment of the Indian prince Porus, his refusal to drink water in Gedrosia when his soldiers had none, and so on. These anecdotes get famous, because they’re the kind of things that fit into documentaries and films very neatly and making for arresting, memorable moments. But there is a tendency to reduce Alexander’s character to just these moments and then end up making him out – in a very Droysen-and-Tarn sort of way – into the “Gentleman Conqueror”.

And that’s just not a reading of Alexander which can survive reading all of any of our key sources on him. The moment you read more than just the genteel anecdotes (“for he, too, is Alexander”, – though note that Alexander’s gentle words do not keep him from trying to use Darius’ family to extort Darius out of his kingdom, Arr. Anab. 2.14.4-9), I think one must concede that Alexander was quite ruthless, a man of immense violence. I mean, and I want to stress this, he killed one of his closest companions with a spear in a drunken rage. I do not think there is a collection of polite-but-witty one-liners to make up for that. But Cleitus was hardly the only person Alexander killed.

Alexander had Bessus, the assassin of Darius, mutilated by having his nose and ears cut off before being executed (Arr. Anab. 4.7.3). He has 2,000 survivors of the sack of Tyre crucified on the beach (Q. Curtius Rufus 4.4.14-17). Because he resisted bravely and wouldn’t kneel, Alexander had the garrison commander at Gaza dragged to death by having his ankles pierced and tied to a chariot (Q. Curtius Rufus 4.4.29). Early in his reign, Alexander sacks Thebes and butchers the populace, as Arrian notes, “sparing neither women nor children” (Arr. Anab. 1.8.8; Arrian tries, somewhat lamely, to distance Alexander from this saying it was is Boeotian allies who did most – but not all – of the killing). Of the Greek mercenaries enrolled in the Persian army at Granicus – a common thing for Greek soldiers to do in this period – Arrian (Anab. 1.16.6) reports that he enslaved them, despite, as Plutarch notes, the Greeks holding in good order and attempting to surrender under terms before they were engaged (Plut. Alex. 16.13). Not every opponent of Alexander gets Porus’ reward for bravery and pride.

Meanwhile, Alexander’s interactions, as noted above, with the civilian populace were self-serving and generally imperious. That’s not unusual for ancient armies, but I should note that Alexander’s conduct towards civilians was also no better than the (dismally bad) norm for ancient armies: he foraged, looted what he wanted, occasionally burned things (including significant parts of Persepolis, the Persian capital), seized land and laborers for his colonies and so on. Alexander’s operations in Central Asia seem to have been particularly brutal: when the populace fled to fortified settlements, Alexander’s orders were to storm each one in turn, killing all of the men and enslaving all of the women and children (Arr. Anab. 4.2.4, note also 4.6.5, doing the same in Marakanda).

And this, at least, brings back to our original question: Was Alexander “Great”? In a sense, I think the expectation in this question is to deliver a judgment on Alexander, but I think its actual function is to deliver a judgment on us.

The Alexander we have in our sources – rather than in the imperialistic hagiographies of him that still condition so much popular memory – seems to have been a witty, charismatic, but arrogant, paranoid and violent fellow. As I joke to my students, “Alexander seems to have enjoyed two things in life, killing and drinking and he was only good at the former”. He could be gentle and witty, but it seems, especially towards the end of his reign, was more often proud, imperious and murderous.

He was at best an indifferent administrator and because he was so indifferent to that task, most of his rule amounted to questions of the men he chose to do the job for him, and those choices were generally quite poor. He made no meaningful preparations for the survival of his empire, his family or his friends upon his death; Arrian (Anab. 7.26.3) reports famously that his last words were, when pushed by his companions to name a successor, τῷ κρατίστῳ (toi kratistoi), “to the strongest”. Translation: kill each other for it. And they did, killing every member of Alexander’s family in the process.1

He was not a great judge of men – for every Perdiccas, there is a Harpalus – or a great military innovator. He largely used the men and the army that his father gave him, and where he deviated from the men, the replacements were generally inferior. That said, he was an astounding commander on campaign and on the battlefield, managing the complex logistics of a massive operation excellently (until his pride got the better of him in Gedrosia) and managing his battles with unnatural calm, skill and luck. He was also, fairly clearly, a good fighter in the personal sense. Alexander was a poor ruler and a lack-luster king, but he was extremely good at destroying, killing and enslaving things.

To the Romans – who first conferred the title “the Great” on Alexander, so far as we know (he is Alexander Magnus first in Plautus’ Mostellaria 775 (written likely in the late 200s)) – that was enough for greatness. And of course it was enough for his Hellenistic successors, who patterned themselves off of Alexander; Antiochus III even takes the title megas (“the Great”) in imitation of Alexander after he reconquers the Persian heartland. Evidently by that point, if not earlier, the usage had slipped into Greek (it may well have started in Greek, of course; Plautus’ comedies are adapted from Greek originals). It should be little shock that, for the Romans, this was enough: this was a culture that reserved their highest honor, the triumph, for military glory alone. And it was clearly enough for Droysen and Tarn too: to be good at killing things and then hamfistedly attempt – and mostly fail – to civilize them, after all, was what made the German and British Empires great. It had to be enough, or else what were all of those Prussian officers and good Scottish gentlemen doing out there with all of that violence? To question Alexander might mean questioning the very system those men served.

What is greatness? Is it pure historical impact, absent questions of morality, or intent? If that is the case, Alexander was Great, because he killed an exceptionally large number of people and in so doing set off a range of historical processes he hadn’t intended (the one he did intend, fusing the Macedonian and Persian ruling class, didn’t really happen) which set off an economic boom and created the vibrant Hellenistic cultural world, outcomes that Alexander did not intend at all. This is a classic “great, but not good” formulation: we might as well talk of “Chinggis the Great”, “Napoleon the Great” or (more provocatively) “Hitler the Great” for their tremendous historical impact. Yet this is a definition that can be sustained, but which robs “greatness” of its value in emulation.

One cannot help but suspect in many of these circumstances, “greatness” is about killing larger numbers of people, so long as they are strange people who live over yonder and dress and pray differently than we here do. It is ironic that Tarn credited Alexander with imagining the unity of mankind, given that Alexander was in the process of butchering however many non-Macedonians was required to set up a Macedonian ethnic ruling class over all other peoples. One suspects, for Droysen and Tarn, it was “greatness”, to be frank, because they understood the foot inside the boot Alexander was planting on the necks of the world, was European and white and so were they. In that vision, greatness is “our man” as opposed to “their man”. But that is such a small-minded, petty form of greatness, “our killer and not your killer”.

Does greatness require something more? The creation of something enduring, perhaps? Alexander largely fails this test, for it is not Alexander but the men who came after him, who exterminated his royal line and built their kingdoms on the ashes of his, who constructed something enduring. Perhaps greatness requires making the world better? Or some kind of greatness of character? For these, I think, it is hard to make Alexander fit, unless one is willing, like Tarn was, to bend and break the narrative to force it. Had Alexander, in fact, been Diogenes (Plut. Alex. 14.1-5), rather than Alexander, but with his character – witty, charismatic, but imperious, arrogant and quick to violence – I do not think we would admire him. As for making the world better, Alexander mostly served to destroy a state he does not seem to have had the curiosity or cultural competence to understand, as Reames puts, it, “not King of Asia, but a Macedonian conqueror in a long, white-striped purple robe” (op. cit. 212). He surely did not understand their religions.2

In a sense, Alexander, I think, serves as a mirror for us. We question the greatness of Alexander and what is revealed are the traits, ideals, and actions we value. Alexander’s oversized personality is as captivating and charismatic now as it was then, and his record as a killer and conqueror is nearly unparalleled. But what is striking about Alexander is that beyond that charisma and military skill there is almost nothing else, which is what makes the test so discerning.

And so I think we continue to wrestle with the legacy and value of Alexander III of Macedon.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: On the Reign of Alexander III of Macedon, the Great? Part II”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-05-24.

- I thus find it funny that every few years another “inspiring” anecdote about Alexander’s wise last words filters around the internet that Alexander’s actual reported last words were so grim and heartless.

- On this, see F. Naiden, Soldier, Priest and God (2018).

October 24, 2025

The future is feminine … maybe

William M. Briggs celebrates the feminine future by celebrating the end of a matriarchy in Greek mythology:

An obvious cause, but of course not the sole problem, is our anti-discrimination laws. These enforce DIE and the Great Feminization (David Stove, decades ago, saw it all coming in his essay “Jobs for the Girls“), which always choke out even hints of manliness. A solution would thus seem to be expurgating this great and terrible body of enervating law.

Alas, that would require men. Congress is unable even to decide what time it is. It will never summon the testicular fortitude to cancel the Civil Rights Act. It does not need to be so.

Perhaps you recall Mary Renault’s The King Must Die, which tells the tale of Theseus and his slaying of the Minotaur. Theseus travels to Athens to fulfill his destiny, but must first pass through Eleusis, where he finds himself in a battle to the death with the King. He wins, but discovers that King is only a ceremonial role; the occupant’s main job is to die each year. During his year-long reign, all his appetites are sated by the queen and her attendants, and he becomes weak.

Eleusis is, of course, a matriarchy. The culture enslaved to a desultory Earth Mother cult. The men soft and unable to deal with hostile neighbors. Theseus bucks tradition, gathers a group of men, the Companions, and goes out to take care of business. He then marches back into Eleusis and declares the restoration of the patriarchy. The queen, in one last defiant girl-boss move, reveals she has taken an abortifacient to kill Theseus’s child. She takes poison and sails off to die.

Theseus installs his Companions into all key positions, institutes a new religion based on knowledge instead of human sacrifice, instructs the men their time in the Longhouse is over, and that is that. The transition takes place in a day.

That is the most true-to-life part of the novel. That instant switch. After all, if the men were united, what could the women do? Women applying force and violence only happens in the movies. Women call for men to do violence on their behalf. But if men have the courage to say no, then that is that.

Now, of course, men do not say no, argues Andrews, and do not have the courage to, either. The Longhouse issues edicts and the men obey, their own appetites well enough satisfied. What next?

Our own John Carter reasons, correctly I think, that the Great Feminization is self-limiting.

It’s also probably no accident that the Trump administration seems to care a lot more about what the anons of the Online Right say than it does about the opinion of the universities or the news media. All the intelligent young men got pushed out of the institutions, and those ionized particles of free male energy then began to self-assemble online into an ad hoc competence hierarchy where prestige is measured by clout rather than professional degrees, job titles, or institutional affiliations. The anon swarm is entirely informal, meaning that its outcomes are not amenable to antidiscrimination legislation or to procedural manipulation; you can screw with the algo all you want but you can’t actually force people to care what women say just because they’re women (thereby placing women into the position of openly trading in thirst, which gets them attention but certainly doesn’t mean that anyone has to pretend to take them seriously).

All that’s happened so far is that people’s attention has been redirected away from crazy woke females and towards the influencers of the online right. The fever has broken but society is a long way from recovered. The institutions are still under the control of crazy woke females, and this is extremely bad, especially because they are — for biological reasons related to childlessness — only going to get crazier as time goes on. Fortunately no one really cares what they say anymore, so as they throw tantrums as the institutions are reclaimed over the next decade or so, their protests won’t register as anything but irrelevant toddler noise.

We still have to hurdle those “rights” laws, because they are still driving behavior of all large organizations. They can be purged or be forgotten. To purge requires Theseus-like courage. To forget requires we first suffer.

Get ready to suffer.

October 23, 2025

QotD: The importance of ancestor veneration to pre-Christian cultures

John: The claim that the fundamental religion of the Greco-Roman world was ancestor veneration, and that everything else was incidental to or derivative from that, is so interesting. I’m not conversant enough with the ancient sources to know whether Fustel de Coulanges is overstating this part, but if you imagine that he’s correct, a lot of other things click into place. For instance, he does a good job showing why it leads pretty quickly to extreme patrilineality, much as it did in the one society that arguably placed even more of an emphasis on ancestor veneration — Ancient China.

And like in China, what develops out of this is an entire domestic religion, or rather a million distinct domestic religions, each with its own secret rites. In China there were numerous attempts over the millennia to standardize a notion of “correct ritual”, none of which really succeeded, until the one-two punch of communism and capitalism swept away that entire cultural universe. But for thousands of years, every family (defined as a male lineage) maintained its own doctrine, its own historical records, its own gods and hymns and holy sites. It’s this fact that makes marriage so momentous. The book has a wonderfully romantic passage about this:

Two families live side by side; but they have different gods. In one, a young daughter takes a part, from her infancy, in the religion of her father; she invokes his sacred fire; every day she offers it libations. She surrounds it with flowers and garlands on festal days. She asks its protection, and returns thanks for its favors. This paternal fire is her god. Let a young man of the neighboring family ask her in marriage, and something more is at stake than to pass from one house to the other.

She must abandon the paternal fire, and henceforth invoke that of the husband. She must abandon her religion, practice other rites, and pronounce other prayers. She must give up the god of her infancy, and put herself under the protection of a god whom she knows not. Let her not hope to remain faithful to the one while honoring the other; for in this religion it is an immutable principle that the same person cannot invoke two sacred fires or two series of ancestors. “From the hour of marriage,” says one of the ancients, “the wife has no longer anything in common with the religion of her fathers; she sacrifices at the hearth of her husband.”

Marriage is, therefore, a grave step for the young girl, and not less grave for the husband; for this religion requires that one shall have been born near the sacred fire, in order to have the right to sacrifice to it. And yet he is now about to bring a stranger to this hearth; with her he will perform the mysterious ceremonies of his worship; he will reveal the rites and formulas which are the patrimony of his family. There is nothing more precious than this heritage; these gods, these rites, these hymns which he has received from his fathers, are what protect him in this life, and promise him riches, happiness, and virtue. And yet, instead of keeping to himself this tutelary power, as the savage keeps his idol or his amulet, he is going to admit a woman to share it with him.

Naturally this reminded me of the Serbs. Whereas most practitioners of traditional Christianity have individual patron saints, Serbs de-emphasize this and instead have shared patrons for their entire “clan” (defined as a male lineage). Instead of the name day celebrations common across Eastern Europe, they instead have an annual slava, a religious feast commemorating the family patron, shared by the entire male lineage. Only men may perform the ritual of the slava, unmarried women share in the slava of their father. Upon marriage, a woman loses the heavenly patronage of her father’s clan, and adopts that of her husband, and henceforward participates in their rituals instead. It’s … eerily similar to the story Fustel de Coulanges tells. Can this really be a coincidence, or have the Serbs managed to hold onto an ancient proto-Indo-European practice?1 I tend towards the latter explanation, since that would be the most Serbian thing ever.

But I’m more interested in what all this means for us today, because with the exception of maybe a few aristocratic families, this highly self-conscious effort to build familial culture and maintain familial distinctiveness is almost totally absent in the Western world. But it’s not that hard! I said before that the patrilineal domestic worship of ancient China was annihilated in the 20th century, but perhaps that isn’t quite as true as it might at first appear. I know plenty of Chinese people with the ability to return to their ancestral village and consult a book that records the names and deeds of their male-lineage ancestors going back thousands of years. These aren’t aristocrats,2 these are normal people, because this is just what normal people do. And I also know Chinese people named according to generation poems written centuries ago, which is a level of connection with and submission to the authority of one’s ancestors that seems completely at odds with the otherwise quite deracinated and atomized nature of contemporary Chinese society.

Perhaps this is why I have an instinctive negative reaction when I encounter married couples who don’t share a name. I don’t much care whether it’s the wife who takes the husband’s name or the husband who takes the wife’s, or even both of them switching to something they just made up (yeah, I’m a lib).3 But it just seems obvious to me on a pre-rational level that a husband and a wife are a team of secret agents, a conspiracy of two against the world, the cofounders of a tiny nation, the leaders of an insurrection. Members of secret societies need codenames and special handshakes and passwords and stuff, keeping separate names feels like the opposite — a timorous refusal to go all-in.

And yet, literally the entire architecture of modern culture and society4 is designed to brainwash us into valuing our individual “autonomy” too much to discover the joy that comes from pushing all your chips into the pot. Is there any hope of being able to swim upstream on this one? What tricks can we steal from weak-chinned Habsburgs and the Chinese urban bourgeoisie?

Jane: I have a friend whose great-grandmother was one of four sisters, and to this day their descendants (five generations’ worth by now!) get together every year for a reunion with scavenger hunts and other competitions color-coded by which branch they’re from. Ever since I heard this story, one of my goals as a mother has been to make the kind of family where my grandchildren’s grandchildren will actually know each other, so I’ve thought a lot about how to do that.

On an individual level, you can get pretty far just by caring. People — children especially, but people more generally — long to know who they are and where they came from. In a world where they don’t get much of that, it doesn’t take many stories about family history and trips “home” to inculcate a sense a “fromness”: some place, some people.5 Our kids have this, I think, and it’s almost entirely a function of (1) their one great-grandparent who really cared and (2) the ancestral village of that branch of the family, which they’ve grown up visiting every year. Nothing builds familial distinctiveness like praying at the graves of your ancestors! But that doesn’t scale, because we’re a Nation of Immigrants(TM) and we mostly don’t have ancestral villages. (The closest I get is Brooklyn, a borough I have never even visited.) And even for the fraction of Americans whose ancestors were here before 1790 (or 1850, or whatever point you choose as the moment just before urbanization and technological innovation began to really dislocate us), the connection to people and place grows yearly more strained.

For the highly mobile professional-managerial class, moving for that new job, it’s even worse. You and I live where we live not because we like it particularly, or because we have roots here, but because it’s what made sense for work. And though we sometimes idly talk about moving somewhere with better weather and more landscape (not even a prettier landscape, just, you know, more), I don’t think any of the places we’d consider have a sufficiently diverse economic base that I’d bet on them being able to support four households worth of our children and grandchildren. We often think of living in your hometown in order to stay connected to your family as a sacrifice that children make — hanging out a shingle in the third largest town in Nebraska rather than heading to New York for Biglaw or something like that — but I increasingly see giving your children a hometown they can reasonably stay in as a sacrifice that we can make as parents.

Fustel de Coulanges has this beautiful, poetic passage about the relationship between the individual and the family:

To form an idea of inheritance among the ancients, we must not figure to ourselves a fortune which passes from the hands of one to those of another. The fortune is immovable, like the hearth, and the tomb to which it is attached. It is the man who passes away. It is the man who, as the family unrolls its generations, arrives at his house appointed to continue the worship, and to take care of the domain.

I love this as a metaphor. It’s generational thinking on steroids: it’s not just “plant trees for your grandchildren to enjoy”, it’s “don’t sell the timberland to pay your bills because it’s your grandchildren’s patrimony”. And there’s something to it, especially when the woods are inherited, because it’s your duty to pass along what was passed down to you. You should be bound by the past, you should be part of something greater than yourself, because the “authentic you” is an incoherent half-formed ball of mutually contradictory desires and lizard-brain instinct. It’s the job of your family and your culture (but I repeat myself) to mold “you” into something real, like the medieval bestiaries though mother bears did to their cubs. But take it literally, as Fustel de Coulanges insists the ancients did, and it feels too much like playing Crusader Kings for me to be entirely comfortable. Yeah, this time my player heir is lazy and gluttonous, but his son looks like he’s shaping up okay, maybe we’ll go after Mecklenburg in thirty years or so. The actual individual is basically incidental to the process. And the entire ancient city is built of this!

The book describes how several families (and it’s worth noting that this includes their slaves and clients; the family here is the gens, which only aristocrats have) come together to form a φρᾱτρῐ́ᾱ or curia, modeled exactly after the family worship with a heroic ancestor, sacred hearth, and cult festivals. Then later several phratries form a tribe, again with a god and rites and patterns of initiation, and then the tribes found a city, each nested intact within the next level up, so that the city isn’t just a conglomeration of people living in the same place, it’s a cult of initiates who are called citizens. And, as in the family, the individual is really only notable as the part of this vast diachronic entity that’s currently capable of walking around and performing the rites. The ancient citizen is the complete opposite of the autonomous, actualized agent our society valorizes, which makes it a useful corrective to our excesses. That image of the family unrolling, of the living man as the one tiny part that’s presently above ground, is something we deracinated moderns would do well to guard in our hearts. But that doesn’t make it true.

Almost by accident, in showing us what inheritance and family meant for the ancient world, Fustel de Coulanges illustrates why Christianity is such a revolutionary doctrine. For the ancients, the son and heir is the one who will next hold the priesthood in the cult of his sacred ancestor. In Christ, we are each adopted into sonship, each made the heir of the Creator of all things, “no more a servant, but a son; and if a son, then an heir of God through Christ”.

Jane and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: The Ancient City, by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-02-20.

- Speaking of ancient proto-Indo-European practices, his descriptions of the earliest Greek and Roman marriage ceremonies are also fascinating. They incorporate a stylized version of something very reminiscent of Central Asian bride kidnapping! I like to think this is also a holdover of some unfathomably old custom, rather than convergent evolution.

- IMO China never really regained a true aristocracy after Mongol rule and the upheavals preceding the establishment of the Ming dynasty.

- The trouble with hyphenation is, what do you do the following generation? I know people are bad at thinking about the future, but come on, you just have to imagine this happening one more time. In fact, the brutally patrilineal Greeks and Romans and Chinese were more advanced than us in recognizing a simple truth about exponential growth. Your ancestors grow like 2^N, which means their contribution gets diluted like 1/(2^N), unless you pick an arbitrary rule and stick with it.

- With the exception of the Crazy Rich Asians movie. Maybe the Chinese taking over Hollywood will slowly purge the toxins from our society. Lol. Lmao.

- Sometimes, as with the Habsburgs, it becomes cringe.