In 2005, [Gertrude Himmelfarb] published The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments. It is a provocative revision of the typical story of the intellectual era of the late eighteenth century that made the modern world. In particular, it explains the source of the fundamental division that still doggedly grips Western political life: that between Left and Right, or progressives and conservatives. From the outset, each side had its own philosophical assumptions and its own view of the human condition. Roads to Modernity shows why one of these sides has generated a steady progeny of historical successes while its rival has consistently lurched from one disaster to the next.

By the time she wrote, a number of historians had accepted that the Enlightenment, once characterized as the “Age of Reason”, came in two versions, the radical and the skeptical. The former was identified with France, the latter with Scotland. Historians of the period also acknowledged that the anti-clericalism that obsessed the French philosophes was not reciprocated in Britain or America. Indeed, in both the latter countries many Enlightenment concepts — human rights, liberty, equality, tolerance, science, progress — complemented rather than opposed church thinking.

Himmelfarb joined this revisionist process and accelerated its pace dramatically. She argued that, central though many Scots were to the movement, there were also so many original English contributors that a more accurate name than the “Scottish Enlightenment” would be the “British Enlightenment”.

Moreover, unlike the French who elevated reason to a primary role in human affairs, British thinkers gave reason a secondary, instrumental role. In Britain it was virtue that trumped all other qualities. This was not personal virtue but the “social virtues” — compassion, benevolence, sympathy — which British philosophers believed naturally, instinctively, and habitually bound people to one another. This amounted to a moral reformation.

In making her case, Himmelfarb included people in the British Enlightenment who until then had been assumed to be part of the Counter-Enlightenment, especially John Wesley and Edmund Burke. She assigned prominent roles to the social movements of Methodism and Evangelical philanthropy. Despite the fact that the American colonists rebelled from Britain to found a republic, Himmelfarb demonstrated how very close they were to the British Enlightenment and how distant from French republicans.

In France, the ideology of reason challenged not only religion and the church, but also all the institutions dependent upon them. Reason was inherently subversive. But British moral philosophy was reformist rather than radical, respectful of both the past and present, even while looking forward to a more enlightened future. It was optimistic and had no quarrel with religion, which was why in both Britain and the United States, the church itself could become a principal source for the spread of enlightened ideas.

In Britain, the elevation of the social virtues derived from both academic philosophy and religious practice. In the eighteenth century, Adam Smith, the professor of moral philosophy at Glasgow University, was more celebrated for his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) than for his later thesis about the wealth of nations. He argued that sympathy and benevolence were moral virtues that sprang directly from the human condition. In being virtuous, especially towards those who could not help themselves, man rewarded himself by fulfilling his human nature.

Edmund Burke began public life as a disciple of Smith. He wrote an early pamphlet on scarcity which endorsed Smith’s laissez-faire approach as the best way to serve not only economic activity in general but the lower orders in particular. His Counter-Enlightenment status is usually assigned for his critique of the French Revolution, but Burke was at the same time a supporter of American independence. While his own government was pursuing its military campaign in America, Burke was urging it to respect the liberty of both Americans and Englishmen.

Some historians have been led by this apparent paradox to claim that at different stages of his life there were two different Edmund Burkes, one liberal and the other conservative. Himmelfarb disagreed. She argued that his views were always consistent with the ideas about moral virtue that permeated the whole of the British Enlightenment. Indeed, Burke took this philosophy a step further by making the “sentiments, manners, and moral opinion” of the people the basis not only of social relations but also of politics.

Keith Windschuttle, “Gertrude Himmelfarb and the Enlightenment”, New Criterion, 2020-02.

March 5, 2025

QotD: British and French Enlightenments

December 17, 2024

QotD: Capitalism is a combination of laziness, stupidity, and greed

… But we can approach this the other way too, looking at capitalism rather than engineering. As Adam Smith didn’t quite say (but as I do, often) capitalists are lazy, stupid and greedy. Finding that new way to make money is really difficult. So, very few try. Once someone does try and find then all the lazy — and greedy, did I mention that? — capitalist bastards copy what is being done. This hauls vast amounts of capital into that area, competition erodes the profits being made by the pioneer and the end result is that it’s consumers who make out like bandits. The result (here) is that the entrepreneur makes 3% or so of the money and the consumers near all the rest. This is the very thing that makes this capitalist and free market thing work.

Tim Worstall, “Folks Are Copying SpaceX – That’s How Capitalism Works”, It’s all obvious or trivial except …, 2024-09-16.

January 20, 2024

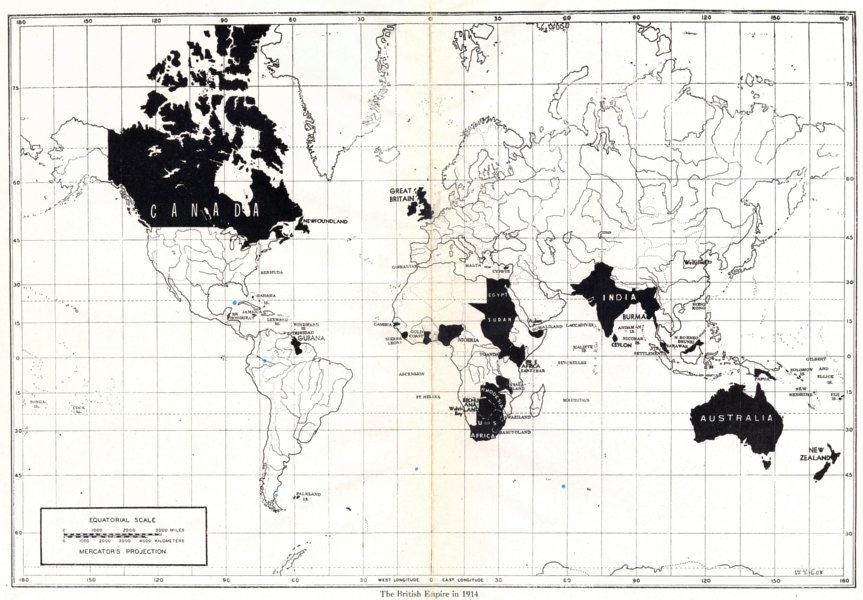

The British Empire would have failed a proper cost-benefit analysis

At the Institute of Economic Affairs, Kristian Niemietz is working on a paper on the economics of empire that, as he shows in this article, indicates that the empire was never a winning economic proposition for Britain as a whole, no matter how well certain well-connected individuals and companies benefitted:

But is it actually true that imperialism makes countries richer? Does imperialism make economic sense?

This question was already hotly debated at the heyday of imperialism. Adam Smith believed that the British Empire would not pass a cost-benefit test:

The pretended purpose of it was to encourage the manufactures, and to increase the commerce of Great Britain. But its real effect has been to raise the rate of mercantile profit, and to enable our merchants to turn into a branch of trade, of which the returns are more slow and distant than those of the greater part of other trades, a greater proportion of their capital than they otherwise would have done […]

Great Britain derives nothing but loss from the dominion which she assumes over her colonies.

He believed that Britain would be better off if it dissolved its Empire:

Great Britain would not only be immediately freed from the whole annual expense of the peace establishment of the colonies, but might settle with them such a treaty of commerce as would effectually secure to her a free trade, more advantageous to the great body of the people, though less so to the merchants, than the monopoly which she at present enjoys.

The liberal free-trade campaigner Richard Cobden agreed:

[O]ur naval force, on the West India station […], amounted to 29 vessels, carrying 474 guns, to protect a commerce just exceeding two millions per annum. This is not all. A considerable military force is kept up in those islands […]

Add to which, our civil expenditure, and the charges at the Colonial Office […]; and we find […] that our whole expenditure, in governing and protecting the trade of those islands, exceeds, considerably, the total amount of their imports of our produce and manufactures.

If imperialism was a loss-making activity – why did Britain and other European colonial empires engage in it for so long?

Smith and Cobden explained it in terms of clientele politics (or Public Choice Economics, as we would say today). Somebody obviously benefited, even if the nation as a whole did not. And the beneficiaries were politically better organised than those who footed the bill.

This proto-Public Choice case against imperialism was not limited to political liberals. Otto von Bismarck, the Minister President of Prussia and future Chancellor of the German Empire, hated liberals in the Smith-Cobden tradition, but he rejected colonialism in terms that almost make him sound like one of them:

The supposed benefits of colonies for the trade and industry of the mother country are, for the most part, illusory. The costs involved in founding, supporting and especially maintaining colonies […] very often exceed the benefits that the mother country derives from them, quite apart from the fact that it is difficult to justify imposing a considerable tax burden on the whole nation for the benefit of individual branches of trade and industry [translation mine].

In his writing about the economics of imperialism, even Michael Parenti, a Marxist-Leninist political scientist (who is, for obvious reasons, popular among Twitter hipsters), sounds almost like a Public Choice economist:

[E]mpires are not losing propositions for everyone. […] [T]he people who reap the benefits are not the same ones who foot the bill. […]

The transnationals monopolize the private returns of empire while carrying little, if any, of the public cost. The expenditures needed […] are paid […] by the taxpayers.

So it was with the British empire in India, the costs of which […] far exceeded what came back into the British treasury. […]

[T]here is nothing irrational about spending three dollars of public money to protect one dollar of private investment – at least not from the perspective of the investors.”

This leads us to a curious situation. Today’s woke progressives disagree with their comrade Parenti on the economics of empire, but they do agree with Britain’s old imperialists, who argued that the Empire was vital for Britain’s prosperity.

December 8, 2023

QotD: Prices as information

Price = information, gang. Adam Smith said that any item’s real value is what its purchaser is willing to pay, and this is exactly the kind of thing he was talking about.

Let’s all take another huge toke and return to our Libertarian paradise, where all conceivable information is both completely accurate and totally free to circulate. And since we’re now all so very, very mellow, let’s give Karl Marx due credit. One of his main gripes with “capitalism” is that it “commodifies” everything. Everything has its price under “capitalism”, Marx said, even stuff that shouldn’t – human life, human dignity. Since this is a college classroom and I’m the prof, I can assign some homework. Go google up “kid killed over sneakers”. You can always find stories like that. Put your natural, in-many-ways-admirable young person’s urge to rationalize aside, and simply consider the information. What were those Air Jordans really worth, based on the stuff we’ve learned today?

See what I mean? Marx had a point. What are those sneakers worth, considered from the standpoint of “demand”? Obviously more than whatever a human life is worth, considered from the same standpoint. Hence Marxism’s enduring appeal to young people whose hearts are in the right place. “Commodificiation”, or “reification” as he sometimes called it, is very real, and very nasty …

Severian, “Velocity of Information (I)”, Founding Questions, 2020-12-26.

August 2, 2020

QotD: Marx’s imperfect economic understanding

We’re at the 200th anniversary of Karl Marx’s birth – also the 201st of Ricardo’s publication, the 242nd of Smith’s Wealth of Nations. And it has to be said that the latter two were more perceptive analysts of the human condition and also contributed vastly more to human knowledge and happiness. Most of the bits that Marx got right in economics were in fact lifted from those other two. The one big thing he got wrong was not to believe them about markets.

We can find, if we look properly, Marx’s insistences of how appalling monopoly capitalism would be in Smith. They’re both right too, it would be appalling. But we do have to understand what they both mean by this. In modern terms they mean monopsony, more specifically the monopoly buyer of labour. What is it that prevents this? Competition in the market among capitalists for access to the labour they desire to exploit. That very competition decreasing the amount of grinding of faces into the dust they’re able to do. Henry Ford’s $5 a day is an excellent example of this very point.

Ford wanted access to the best manufacturing labour of his time. He also wanted to have a lower turnover of that labour, lower training costs. So, he doubled wages (actually, normal wages plus a 100% bonus if you did things the Ford Way) and got that labour. At which point all the other manufacturers had to try and compete with those higher wages in order to get that labour they wanted to expropriate the sweat of the brow from. Marx did get this, he pointed out that exactly this sort of competition, in the absence of a reserve army of the unemployed, is what would raise real wages as productivity improved.

Smith also didn’t like the setting of wages as it precluded just such competition and such wage rises.

Where Marx went wrong was in not realising this power of markets. He knew of them, obviously, understood the idea, but just didn’t understand their power to ameliorate, destroy even, that march to monopoly capitalism.

[…]

The thing we really need to know on this bicentenary about Karl Marx is that he was wrong. He just never did grasp the power of markets to disrupt, even prevent, the tendencies he saw in capitalism. Specifically, and something we all need to know today, the power of competition among capitalists as the method of improving the lives of all us wage slaves. You know, that’s why we proletariat today, exploited as we are and ground into the dust, are the best fed, longest lived and richest, in every sense of the word, human beings who have ever existed. Something which is, if we’re honest about it, not a bad recommendation for a socio-economic system really. You know, actually working? Achieving the aim of improving the human condition?

Tim Worstall, “Marx At 200 – Yes, He Was Wrong, Badly Wrong”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-05-04.

May 20, 2020

QotD: Behavioural economics, aka the applied theory of bossing people around

Once [Richard] Thaler has established that you are in myriad ways irrational it’s much easier to argue, as he has, vigorously — in his academic research, in popular books, and now in a column for The New York Times — that you are too stupid to be treated as a free adult. You need, in the coinage of Thaler’s book, co-authored with the law professor and Obama adviser Cass Sunstein, to be “nudged.” Thaler and Sunstein call it “paternalistic libertarianism.”

Adam Smith spoke of “the man of system” who “seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board.” Thaler and his benevolent friends are men, and some few women, of system. They hate the Chicago School, have never heard of the Austrian School, dismiss spontaneous order, and favor bossing people around — for their own good, understand. Employing the third most unbelievable sentence in English (the other two are “The check is in the mail” and “Of course I’ll respect you in the morning”), they declare cheerily, “We’re from the government and we’re here to help.”

We humans face a choice of treating people as children or as adults. A liberal society, Smith’s “liberal plan of [social] equality, [economic] liberty, and [legal] justice,” treats adults as adults. The principle of an illiberal society, from Thaler’s to the much worse kind, is that you are to be corrected not through respectful dialog that treats you as an equal, but by compulsion or trickery, which treats you like a toddler about to walk into traffic.

Wikipedia lists fully 257 cognitive biases. In the category of decision-making biases alone there are anchoring, the availability heuristic, the bandwagon effect, the baseline fallacy, choice-supportive bias, confirmation bias, belief-revision conservatism, courtesy bias, and on and on. According to the psychologists, it’s a miracle you can get across the street.

For Thaler, every one of the biases is a reason not to trust people to make their own choices about money. It’s an old routine in economics. Since 1848, one expert after another has set up shop finding “imperfections” in the market economy that Smith and Mill and Bastiat had come to understand as a pretty good system for supporting human flourishing.

Dierdre McCloskey, “The Applied Theory of Bossing People Around”, Reason, 2018-02-11.

May 16, 2020

QotD: Division of labour in the modern world

… digital devices slow us down in subtler ways, too. Microsoft Office may be as much a drag on productivity as Candy Crush Saga. To see why, consider Adam Smith’s argument that economic progress was built on a foundation of the division of labour. His most celebrated example was a simple pin factory: “One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points” and 10 men together made nearly 50,000 pins a day.

In another example — the making of a woollen coat — Smith emphasises that the division of labour allows us to use machines, even “that very simple machine, the shears with which the shepherd clips the wool”.

The shepherd has the perfect tool for a focused task. That tool needs countless other focused specialists: the bricklayer who built the foundry; the collier who mined fuel; the smith who forged the blades. It is a reinforcing spiral: the division of labour lets us build new machines, while machines work best when jobs have been divided into one small task after another.

The rise of the computer complicates this story. Computers can certainly continue the process of specialisation, parcelling out jobs into repetitive chunks, but fundamentally they are general purpose devices, and by running software such as Microsoft Office they are turning many of us into generalists.

In a modern office there are no specialist typists; we all need to be able to pick our way around a keyboard. PowerPoint has made amateur slide designers of everyone. Once a slide would be produced by a professional, because no one else had the necessary equipment or training. Now anyone can have a go — and they do.

Well-paid middle managers with no design skills take far too long to produce ugly slides that nobody wants to look at. They also file their own expenses, book their own travel and, for that matter, do their own shopping in the supermarket. On a bill-by-the-minute basis none of this makes sense.

Why do we behave like this? It is partly a matter of pride: since everyone has the tools to build a website or lay out a book, it feels a little feeble to hand the job over to a professional. And it is partly bad organisational design: sacking the administrative assistants and telling senior staff to do their own expenses can look, superficially, like a cost saving.

Tim Harford, “Why Microsoft Office is a bigger productivity drain than Candy Crush Saga”, The Undercover Economist, 2018-02-02.

April 12, 2019

QotD: Money is not wealth

If you want to create wealth, it will help to understand what it is. Wealth is not the same thing as money.* Wealth is as old as human history. Far older, in fact; ants have wealth. Money is a comparatively recent invention.

Wealth is the fundamental thing. Wealth is stuff we want: food, clothes, houses, cars, gadgets, travel to interesting places, and so on. You can have wealth without having money. If you had a magic machine that could on command make you a car or cook you dinner or do your laundry, or do anything else you wanted, you wouldn’t need money. Whereas if you were in the middle of Antarctica, where there is nothing to buy, it wouldn’t matter how much money you had.

Wealth is what you want, not money. But if wealth is the important thing, why does everyone talk about making money? It is a kind of shorthand: money is a way of moving wealth, and in practice they are usually interchangeable. But they are not the same thing, and unless you plan to get rich by counterfeiting, talking about making money can make it harder to understand how to make money.

Money is a side effect of specialization. In a specialized society, most of the things you need, you can’t make for yourself. If you want a potato or a pencil or a place to live, you have to get it from someone else.

How do you get the person who grows the potatoes to give you some? By giving him something he wants in return. But you can’t get very far by trading things directly with the people who need them. If you make violins, and none of the local farmers wants one, how will you eat?

The solution societies find, as they get more specialized, is to make the trade into a two-step process. Instead of trading violins directly for potatoes, you trade violins for, say, silver, which you can then trade again for anything else you need. The intermediate stuff — the medium of exchange — can be anything that’s rare and portable. Historically metals have been the most common, but recently we’ve been using a medium of exchange, called the dollar, that doesn’t physically exist. It works as a medium of exchange, however, because its rarity is guaranteed by the U.S. Government.

The advantage of a medium of exchange is that it makes trade work. The disadvantage is that it tends to obscure what trade really means. People think that what a business does is make money. But money is just the intermediate stage — just a shorthand — for whatever people want. What most businesses really do is make wealth. They do something people want.**

* Until recently even governments sometimes didn’t grasp the distinction between money and wealth. Adam Smith (Wealth of Nations, v:i) mentions several that tried to preserve their “wealth” by forbidding the export of gold or silver. But having more of the medium of exchange would not make a country richer; if you have more money chasing the same amount of material wealth, the only result is higher prices.

** There are many senses of the word “wealth,” not all of them material. I’m not trying to make a deep philosophical point here about which is the true kind. I’m writing about one specific, rather technical sense of the word “wealth.” What people will give you money for. This is an interesting sort of wealth to study, because it is the kind that prevents you from starving. And what people will give you money for depends on them, not you.

When you’re starting a business, it’s easy to slide into thinking that customers want what you do. During the Internet Bubble I talked to a woman who, because she liked the outdoors, was starting an “outdoor portal.” You know what kind of business you should start if you like the outdoors? One to recover data from crashed hard disks.

What’s the connection? None at all. Which is precisely my point. If you want to create wealth (in the narrow technical sense of not starving) then you should be especially skeptical about any plan that centers on things you like doing. That is where your idea of what’s valuable is least likely to coincide with other people’s.

Paul Graham, “How to Make Wealth”, Paul Graham, 2004-04.

September 21, 2018

QotD: “Let us abandon Capitalism, and go back to Adam Smith”

An old friend of mine, among my bosses in late ’seventies Bangkok — Antoine van Agtmael, genuinely admired and loved — was the genius who invented the expression “emerging markets,” to replace that downer, “developing countries.” (Which in turn had been the euphemism for “backward countries.”) It was by such creative hocus-pocus that attitudes towards “Third World” investment were dramatically changed, in the era of Thatcher and Reagan. A man of indomitably good intentions; charitable, selfless, and a brilliant merchant banker; a little leftish in his social and cultural outlook — I give Antoine’s phrase as an example of the sort of poetry that changes the world. I took pride, once, in editing a book of his astute investment “case studies.”

Thirty-six years have passed, since in my youth and naiveté I was draughting a book of my own on what is still called “development economics.” (I was a business journalist in Asia then, who did a little teaching on the side.) It seemed to me that “free enterprise” should be encouraged; that “government intervention” should be discouraged; but that the aesthetic, moral, and spiritual order in one ancient “developing country” after another was being undermined by the success, as also by the frequent failures, not only of foreign but of domestic investors. This bugged me because, like my father before me (who had worked and taught westernizing subjects in this same Third World), my well-intended efforts on behalf of “progress” were ruining everything they touched; everything I loved.

My attempt to explain this, if only to myself, ended in abject failure to answer my central question: “Why does capitalist success make the world ugly and its people sad?”

Only now do I begin to glimpse an answer; and that part of it could be expressed in the imperative, “Let us abandon Capitalism, and go back to Adam Smith.”

David Warren, “In defence of economic backwardness”, Essays in Idleness, 2016-12-01.

September 14, 2018

QotD: Free market capitalism

What is free-market capitalism? Allan Meltzer, an economist at Carnegie Mellon, a Hoover Institution scholar, and onetime advisor to President Ronald Reagan, offers a classic definition. “As long as you engage in actions where your actions don’t impinge upon other people, you’re free to buy and sell anything you want,” he says, adding that free-market capitalism protects private property. Thomas Coleman, a hedge-fund veteran heading up an economic-policy shop at the University of Chicago, adds another key element: free-market capitalism functions best when people and companies can trade “without systemic distortion of prices.” Deirdre McCloskey, until last year a professor at the University of Illinois, and author of the recent book Bourgeois Equality, says, “I don’t like calling it capitalism, anyway, which was a word invented by our enemies. … I call it instead market-tested betterment, innov-ism. … That’s what’s made us rich.” McCloskey says that the heart of “betterment” is Adam Smith’s ideal of “every man to pursue his own interest in his own way” — and that “doesn’t mean a large government sector,” she emphasizes.

Free-market capitalism isn’t the same thing as radical libertarianism. Stan Veuger, an American Enterprise Institute scholar and economics lecturer at Harvard, dismisses what he calls “the anarcho-capitalist ideal”: an economy with no regulations and zero taxation. “There are places like Somalia that score well” on such purist definitions of free markets, he points out. To work well, capitalism needs “an environment where people can concentrate on being productive,” rather than, say, having private armies to assure personal safety. Free-market capitalism requires laws and rules, more than ever, now that more people live in close proximity in dense cities than ever before. Human activity leads to disputes, and disputes can be solved, or at least moderated, by resolutions that govern behavior. We often forget that markets don’t make broad public-policy decisions; governments do. Markets allocate resources under a particular policy regime, and they can provide feedback on whether policies are working. If a city, say, restricts building height to preserve sunlight in a public park, free-market actors will take the restricted supply into account, raising building prices. This doesn’t mean that the city made the wrong decision; it means that the city’s voters will risk higher housing prices in order to preserve access to sunlight. By contrast, a city that restricts housing supply and restricts prices via rent regulation is thwarting market signals — it takes an action and then suppresses the direct consequences of that action.

Nicole Gelinas, “Fake Capitalism: It’s not free markets that have failed us but government distortion of them”, City Journal, 2016-11-06.

August 18, 2018

QotD: Adam Smith and Charles Darwin

… today few people appreciate just how similar the arguments made by Smith and Darwin are. Generally, Adam Smith is championed by the political right, Charles Darwin more often by the left. In, say, Texas, where Smith’s emergent, decentralised economics is all the rage, Darwin is frequently reviled for his contradiction of dirigiste creation. In the average British university, by contrast, you will find fervent believers in the emergent, decentralised properties of genomes and ecosystems who yet demand dirigiste policy to bring order to the economy and society. But if life needs no intelligent designer, then why should the market need a central planner? Where Darwin defenestrated God, Smith just as surely defenestrated Leviathan. Society, he said, is a spontaneously ordered phenomenon. And Smith faces the same baffled incredulity — How can society work for the good of all without direction? — that Darwin faces.

Matt Ridley, The Evolution of Everything, 2015.

January 27, 2018

The difference between being “pro-free market” and “pro-business”

It’s a distinction that really does make a difference, argues Jonah Goldberg:

One of the most difficult distinctions for people in general and politicians in particular to grasp is the difference between being pro-free market and pro-business.

There are many reasons for this confusion. For politicians, the key reason is that businesspeople are constituents and donors, while the free market is an abstraction. Also, because capitalists tend to lionize successful people, we assume they share our philosophical commitments. But it is a rare corporate titan who favors a free market if doing so is bad for his or her bottom line.

Adam Smith recognized this in his canonical 1776 work, The Wealth of Nations. “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion,” he wrote, without the conversation ending “in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

This doesn’t mean that capitalists are evil; it means they’re human beings. Virtually every profession you can think of has a tendency to dig a moat around itself to protect its interests and defend against competition. A few years ago, the American Academy of Pediatrics came out against affordable health care for children. Retail chains like Walmart and CVS started opening in-store clinics to provide affordable basic health care like vaccinations. The pediatricians rightly saw this as a threat to their monopoly over kids’ medical care. Obviously, the pediatricians didn’t think they were villains; they simply found rationalizations for why everyone should keep paying them top dollar for stuff that could be done more cheaply.

Similarly, most teachers like kids, but that doesn’t stop teachers unions from doing everything they can to protect themselves from competition or accountability. Indeed, unions, by design, are conspiracies against the public to defend the wages and perks of their members. NIMBYism (Not in My Backyard) is another manifestation of this phenomenon.

[…]

Smith understood this too. After noting how people of the same trade conspire to raise prices, he added: “It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary.”

What both Smith and the founders understood is that such conspiracies can only last with the help of government. As the economist Joseph Schumpeter argued, in a system of free competition, monopolies cannot long endure without government protection.

December 15, 2017

QotD: Crony capitalism

First, we labor under a ubiquitous threat of being shackled by crony capitalists. [Adam] Smith wondered how internally stable a free market could be in the face of a tendency for its political infrastructure to decay into crony capitalism. (The phrase “crony capitalism” is not Smith’s. I use it to refer to various of Smith’s targets: mercantilists who lobby for tariffs and other trade barriers, monopolists who pay kings for a license to be free from competition altogether, and so on.) Partnerships between big business and big government lead to big subsidies, monopolistic licensing practices, and tariffs. These ways of compromising freedom have been and always will be touted as protecting the middle class, but their true purpose is (and almost always will be) to transfer wealth and power from ordinary citizens to well-connected elites.

David Schmidtz, “Adam Smith on Freedom” (published as Chapter 13 of Ryan Patrick Hanley’s Adam Smith: His Life, Thought, and Legacy, 2016).

October 1, 2017

Deirdre McCloskey on the rise of economic liberty

Samizdata‘s Johnathan Pearce linked to this Deirdre McCloskey article I hadn’t seen yet:

Since the rise during the late 1800s of socialism, New Liberalism, and Progressivism it has been conventional to scorn economic liberty as vulgar and optional — something only fat cats care about. But the original liberalism during the 1700s of Voltaire, Adam Smith, Tom Paine, and Mary Wollstonecraft recommended an economic liberty for rich and poor understood as not messing with other peoples’ stuff.

Indeed, economic liberty is the liberty about which most ordinary people care.

Adam Smith spoke of “the liberal plan of [social] equality, [economic] liberty, and [legal] justice.” It was a good idea, new in 1776. And in the next two centuries, the liberal idea proved to be astonishingly productive of good and rich people, formerly desperate and poor. Let’s not lose it.

Well into the 1800s most thinking people, such as Henry David Thoreau, were economic liberals. Thoreau around 1840 invented procedures for his father’s little factory making pencils, which elevated Thoreau and Son for a decade or so to the leading maker of pencils in America. He was a businessman as much as an environmentalist and civil disobeyer. When imports of high-quality pencils finally overtook the head start, Thoreau and Son graciously gave way, turning instead to making graphite for the printing of engravings.

That’s the economic liberal deal. You get to offer in the first act a betterment to customers, but you don’t get to arrange for protection later from competitors. After making your bundle in the first act, you suffer from competition in the second. Too bad.

In On Liberty (1859) the economist and philosopher John Stuart Mill declared that “society admits no right, either legal or moral, in the disappointed competitors to immunity from this kind of suffering; and feels called on to interfere only when means of success have been employed which it is contrary to the general interest to permit — namely, fraud or treachery, and force.” No protectionism. No economic nationalism. The customers, prominent among them the poor, are enabled in the first through third acts to buy better and cheaper pencils.

[…]

Indeed, economic liberty is the liberty about which most ordinary people care. True, liberty of speech, the press, assembly, petitioning the government, and voting for a new government are in the long run essential protections for all liberty, including the economic right to buy and sell. But the lofty liberties are cherished mainly by an educated minority. Most people — in the long run foolishly, true — don’t give a fig about liberty of speech, so long as they can open a shop when they want and drive to a job paying decent wages. A majority of Turks voted in favour of the rapid slide of Turkey after 2013 into neo-fascism under Erdoğan. Mussolini and Hitler won elections and were popular, while vigorously abridging liberties. Even a few communist governments have been elected — witness Venezuela under Chavez.

December 3, 2016

Capitalists and communists

David Warren notes an odd similarity:

The last generation of Communists in power, in the Soviet Union and elsewhere, suffered from a debilitating foible. They did not themselves believe in the ideology they were preaching. Their efforts were thus directed to getting around the realities their forebears had not anticipated. They thus became their own enemies, working against their own unworkable socialist principles, and in the course of their tireless if frazzled ministrations, the Berlin Wall came down.

Capitalism suffers from the same problem today. The principles of Adam Smith are not seriously believed by any of its nominal advocates. They are not even known. Nor could they be, for like Marx, Smith is not even read. I have derived pleasure, on many occasions, from pointing out to some ideological enthusiast for Capitalism, that its supposed author was refulgently opposed to joint-stock companies. Which is to say, to the form of business ownership that controls — oh, I don’t know — ninety-five percent of the so-called “private sector” economy today?

I observed that, apart from any consideration of morality (and he was, after all, only an amateur economist, but a professional Perfesser of Moral Philosophy), Smith believed that joint-stock companies were inefficient, because essentially bureaucratic. This is inevitable when ownership is separated from management. “Growth,” or Bigness, subtly replaces profit (both mercenary and non-mercenary) as the principal aspiration.

As a general rule of thumb, when you want to get something done, use the smallest possible organization to achieve your desired goal. I always found it a warning sign of future decline when small companies I worked for started to take on the trappings of bigger companies … when the bureaucratic rot began to set in. In some cases, just the transition to having an “HR Department” (rather than managers hiring directly) was enough to trigger bureaucracy growth and efficiency losses.