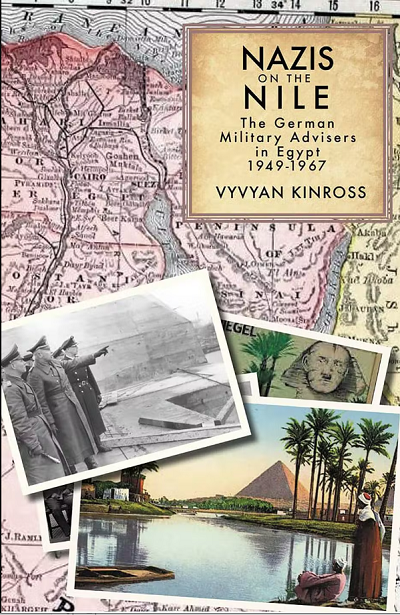

In The Critic, James Barr reviews a book on the roles of former Nazi military and political figures in the Egyptian forces, Nazis on the Nile: The German Military Advisers in Egypt 1949-1967 by Vyvyan Kinross:

One of the paradoxes of the early postwar era is that, after Germany’s defeat, the Nazis were vilified at the same time that their expertise was sought after by both Cold War superpowers. Germans played key roles in both sides’ space programmes. Less infamous is the part they also went on to play in the Egyptian rocket programme, one of the subjects in this fascinating and disturbing book.

After suffering a humiliating defeat in the war that followed the establishment of Israel, the Egyptians wanted revenge. As the British had refused to help them — despite maintaining a deeply unpopular and large presence astride the Suez Canal — Egypt’s sybaritic King Farouq turned to his enemy’s enemy instead. In 1949 he commissioned an Afrika Korps general, Artur Schmitt, to review the Egyptian army.

Having checked in to a Cairo hotel under the name “Herr Goldstein”, Schmitt inspected Egyptian units and went on to Syria to survey Israel from the Golan Heights. The Egyptians’ failure to combine tanks, artillery and infantry effectively, he decided, explained their “inability to take advantage of the early stages of fighting to wipe the State of Israel off the map”.

Schmitt’s forthright conclusions were unwelcome, and he did not stay long. But some younger Egyptian army officers shared his views and, after they had overthrown Farouq in 1952, they picked up where the king had left off. Within days they offered Fritz Voss, the former head of the Skoda arms factory in Pilsen, the job of masterminding the retraining of the army and the establishment of a military industrial base that could produce jet aircraft and missiles.

Voss in turn invited old contacts to join him, including Wilhelm Beisner, an SS officer who had been part of Einsatzkommando Egypt, which would have spearheaded the Holocaust in Palestine had Rommel won at El Alamein. The Germans found Egyptian working conditions challenging. “Here one has to act much more slowly than in Prussia,” complained a German instructor who found “Oriental sloppiness” irritating. Of forty tanks lined up for a parade to celebrate the first anniversary of the coup, just twelve made it past the junta’s rostrum.

The author, Vyvyan Kinross, is a consultant by profession. He has advised Arab governments and clearly understands the fundamental problems. “The battle” for the Germans, he writes, “was always to reconcile finance, resourcing and the expertise required to execute a sophisticated manufacturing process with the challenging conditions and logistics that prevailed in a country that was late to industrialise and financially underpowered.”