Theophilus Chilton on the development of psyops and some examples of their use in US civilian contexts in recent years:

I trust that most readers are familiar with the concept of a “psyop”, a psychological operation designed to sway its targets in certain desired directions. Many of the mechanics of psyops were pioneered by the CIA and other intelligence agencies during the Cold War but have now been turned against civilian populations in the USA and elsewhere in an effort by the Regime to maintain control and minimise opposition to its various agendas. However, I’d like to make the point that psyops qualitatively differ from standard, run-of-the-mill propaganda such as governments have used for millennia.

The difference is primarily that of the time preferences involved. Whether it’s designed to whip up a population against an enemy or to try to obfuscate the truth about some particular event that has occurred, propaganda tends to operate on a shorter timescale and with more limited and simple policy goals in mind. It’s not surprising that modern propaganda techniques share a lot in common with commercial advertising designed to induce an “impulse buy” response in potential customers. Propaganda generally operates the same way — create a monodirectional response to a particular stimulus.

Psyops, on the other hand, are quite a bit more complex and generally involve the building of a narrative memeplex over the course of months, years, or even decades. Psyops are, of course, also fake but theirs is a fakeness that builds upon constant, repetitious narrative-building that lays out a foundational lens through which any individual incident or act can be systematically interpreted, adding them to the overall saga being told.

With conventional propaganda, the aim is to communicate Regime diktat to the average citizen. However, it does not necessarily expect the recipients to believe the propaganda, but merely comply with the goals. The Powers That Be in such cases don’t care why Havel’s greengrocer puts the sign up in his window, but merely that he does so. The primary purpose of psyops, on the other hand, is to ensure compliance by convincing the target to self-comply, rather than it having to be done by outside force or persuasion. It’s always touch and go when you’re making someone outwardly comply but inwardly they’re dissident. When the mark can be convinced to willingly self-police, this makes the government’s job easier since they don’t have to worry about this closet dissidence. The true believer is the best believer.

In essence, propaganda aims for immediate reactive persuasion while psyops seek long-term groundlaying that gives more all-inclusive means of maintaining overarching narrative control.

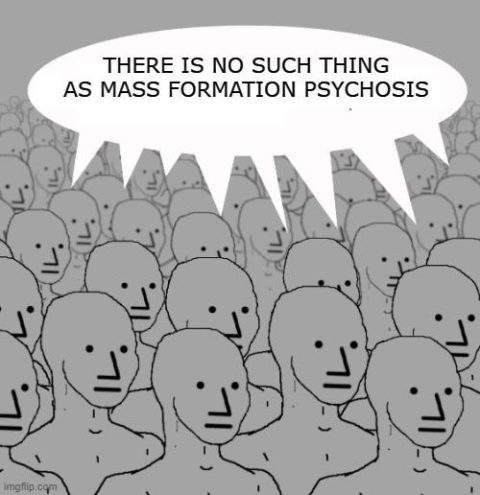

Now, a lot of people out there like to think they’re immune to psyops because “hurr durr I don’t beleeb da media!!” But they’re not. Indeed, a lot of these boomercon types are just as susceptible to psyops as anyone else when the right buttons are pushed. This is because they’ve been primed for it by the systematic, society-wide preparation of the psychological battle space without their ever realising it. In many cases, the foundations for a psyop are so culturally systematic that people don’t even realise what is happening.

For example, there are a ton of people out there who would pride themselves on being independent thinkers who nevertheless believed everything that was peddled during the covid and vaccine psyops. The reason for this is because they want to think of themselves as smart, knowledgeable about science, etc. Smart People believe the Right Things, after all. That, in turn, is the result of decades of psyops that have ensconced “science” as the arbiter of morality and truth in post-Christian America. So even when the science is fake or wrong, it is still accorded a moral authority that it does not deserve.