John E. MacKinnon on the world’s first admittedly genocidal, terminally apologetic, “post-national” state … the entity that used to be known as the Dominion of Canada:

During one broadcast, [late CBC Radio host Peter] Gzowski recalled an incident that had occurred at the annual invitational golf tournament he hosted to benefit adult literacy programs across Canada. As one participant, standing next to Gzowski, leaned thoughtfully on his club, another drove a golf cart over his toes. Although it was unclear from the telling whether the cart-driver was American, the first golfer was obviously Canadian, since, shifting gingerly from foot to aching foot, he could only plead, “sorry”. Gzowski shared this anecdote with evident delight, since it struck him as so endearingly, because emblematically, Canadian.

But Gzowski’s soaring contentment with this view of his country and countrymen was no less emblematic. To Canadian nationalists of Gzowski’s era and ilk, the representative Canadian is no hewer of wood or carrier of water, no builder of bridges, roads and railways, no stormer of barricades or keeper of the peace, but a hobbled guest on a verdant fairway, eagerly apologizing for the pleasure of having his toes crushed. “That is what I like about you Canadians,” says Dr. Gunilla Dahl-Soot in Robertson Davies’s novel The Lyre of Orpheus, “you are so ready to admit fault. It is a fine, if dangerous, national characteristic. You are all ashamed.”

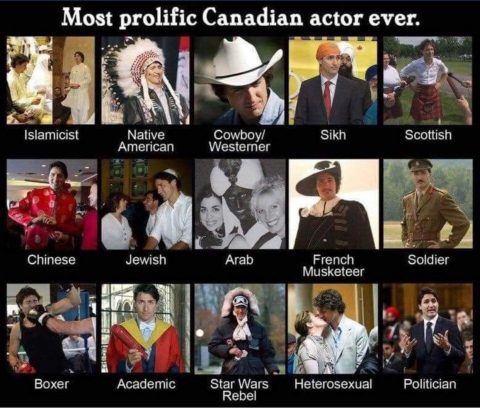

Over the past 200 years, notes Hungarian-born Canadian writer George Jonas, “we have been misled by science. Medicine became our hubris. Having learned to fix appendices, we thought we could fix history.” Today, in Canada, there is no clearer manifestation of this urge to renovate and repair the past than the vogue for apology. And no one has struck this posture of national self-abasement with quite the alacrity of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Just months after taking office, he apologized for the Komagata Maru incident in 1914, in which a ship carrying Sikhs, Muslims, and Hindus was sent back to Calcutta, where 20 died in a riot. In 2017, he apologized to Indigenous residential-school survivors in Newfoundland and Labrador, and, just days later, to LGBT Canadians for decades of “state-sponsored, systemic oppression.” A year later, he apologized for the execution, in 1864, of six Tsilhqot’in chiefs over a road-building dispute, and for a government refusal, in June, 1939, to allow into the port of Halifax the MS St. Louis, an ocean liner carrying more than 900 Jews fleeing Nazi Germany. In March, 2019, he apologized for the inhumane manner in which Inuit in northern Canada were treated for tuberculosis in the mid-20th century. Two months later, he exonerated Chief Poundmaker of the Poundmaker Cree, apologizing for the Chief’s conviction for treason more than 130 years before. Still at it in the spring of 2021, Trudeau issued a formal apology in the House of Commons for the internment of Italian-Canadians during the Second World War, even though many, it was subsequently revealed, were indeed hardcore fascists, loyal to an enemy in a time of war. Two weeks later, he lowered the Canadian flag for five months to mark the discovery of the remains of Indigenous children who died at residential schools.

In the midst of this flurry of breathy performances, the BBC asked, with more than a touch of arch obviousness, whether the Canadian Prime Minister might not perhaps apologize too much. And yet, in Trudeau, we simply have the apotheosis of that habit of abject contrition celebrated by Gzowskian nationalists. Under his government, it has become fashionable, even necessary, to apologize, not just for egregious historical episodes or policies, but for the existence of Canada itself. In an interview with the New York Times, Trudeau witlessly described the country that had so favoured him through a lifetime of privilege as “post-national”, suggesting that Canada as we know it had somehow served its purpose, extended itself beyond any warrantable use. And recently, not to be outpaced by more current styles of denunciation, he described Canada, “in all our institutions,” as “built around a system of colonialism, of discrimination, of systemic racism.” When China, responding to criticism of its brutal treatment of Muslim Uyghurs, lashed out at Canada for committing “genocide” against its own Indigenous population and subjecting Asian-Canadians to “systemic racism”, Canada’s political class was in no position to quibble — as its prime minister had already muttered his agreement to the claim that he presided over a genocide state.

This note of cringing repentance now echoes in the pronouncements of all of our institutions. No matter how admired our country may remain internationally, no matter how ardently people around the world long to immigrate here for a chance at a better life, our presumptive leaders are eager to scorn Canada as a meagre and regrettable conceit. That the confessional mode they favour has become so prevalent confirms what Christopher Lasch long ago diagnosed as the strain of narcissism that courses through contemporary culture, lending ready appeal to all such facile gestures of self-reproach. There is, indeed, no cagier career move for any Canadian academic, journalist, bureaucrat, or politician these days than to repudiate Canada, and with feeling.