World War Two

Published 5 Oct 2021We all know that penicillin is a wonder drug, it shortened the war, and assured Allied victory. Or did it, is that just a myth? The Allies are certainly much further ahead than the Axis, but even with accelerated wartime development, will it come into service quick enough to make a difference?

(more…)

October 6, 2021

Did Penicillin Win World War Two? – WW2 Special

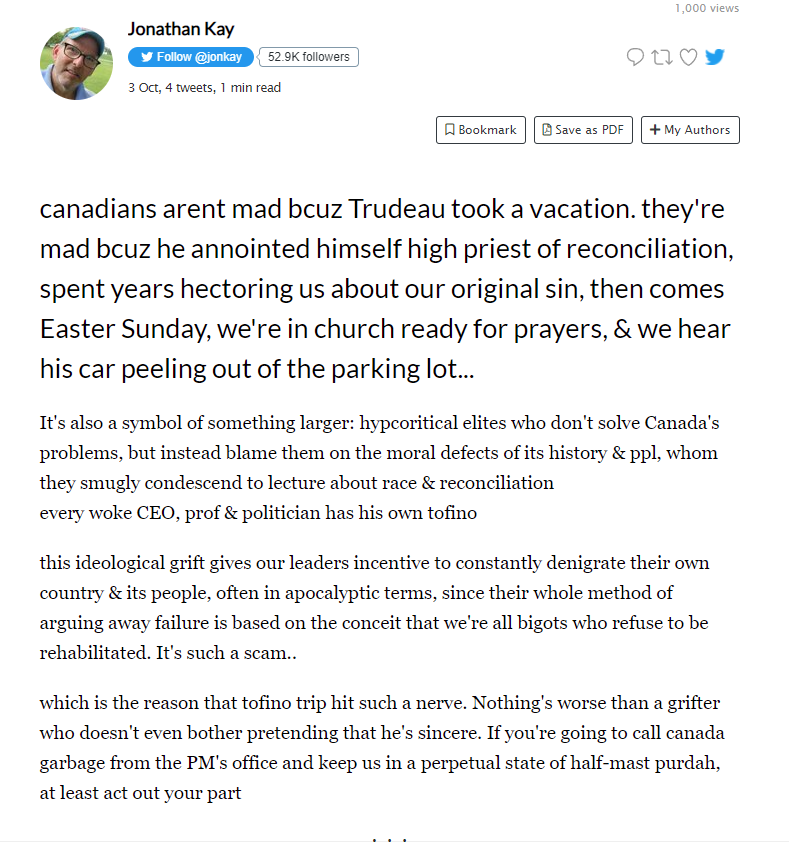

Jonathan Kay explains why Justin Trudeau’s no-show got a lot of Canadians mad

Linked from Small Dead Animals, Jonathan Kay took to the twits to summarize why this particular Justin Trudeau flake-out seems to have impacted his reputation so much more than all the other flake-outs he’s pulled over the years (screencapped for those who find Threadreader links objectionable):

Let’s Visit Finland (1935) – Helsinki Liinakhamari Lapland Arctic Ocean Highway

PeriscopeFilm

Published 2 Aug 2020Love our channel? Help us save and post more orphaned films! Support us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/PeriscopeFilm Even a really tiny contribution can make a difference.

This travelogue film shows Finland in the 1930’s. It was presented by Joseph Harris and Martin Ross. Finland is in northern Europe bordering Sweden, Norway and Russia. The capital city of Helsinki as well as the Arctic Ocean Highway running to the port of Liinakhamari which once touched the Arctic Ocean will be shown. It refers to Helsinki as Helsingfors which is the former Swedish name of the capital. The Arctic Ocean Highway was rerouted after WW2. Finland had long been a battleground due to the imperial ambitions and growing pains of Sweden and Russia. Finland was absorbed by the Russian Empire in 1807 (:32). A 1917 revolution overthrew the Czarist regime (:38). Due to wars and fires, few remnants existed of historical value in Helsinki (:47). Some of the old wooden houses have managed to remain (:53). Granite columns and entryways of the city point to early architects’ desire to use the country’s reserve of granite (1:14). Russian influence is exemplified in a Russian style church (1:35) and the cathedral of St. Nicholas (1:38). Architects sought to stray from the influences of foreign domination (1:45). The red granite railway station in the Market Square (1:59), the parliament building (2:05) and white factory buildings show no allegiance to former occupiers (2:08). A newly erected suburb consisting of flats constructed with reinforced steel (2:26) lay encircled by forests and lakes. Roads are lined with trees and intermittent flower beds (2:49). Helsinki harbor follows (2:59). Town parks and gardens were erected with artistic sculptures throughout showing Finland’s growing appreciation for the arts (3:22). The capital is also the terminus of the road leading northward for over a thousand miles to the port of Liinakhamari (3:34). A map is provided which still has USSR on it as this was before the fall of Soviet Russia (3:35). The port of Liinakhamari lay about 300 miles beyond the polar circle (3:43). The film follows this road which remains concrete for 20 miles after leaving the capitol (3:58). Land alongside had been cleared for agriculture (4:06). A farmer reaps hay with a scythe as modern farm machinery had not yet reached the area (4:34). A striking feature of the Finnish countryside are the impaled corn husks on wooden poles for drying (5:03). A double arched bridge of granite follows crossing one of the waterways along the route (5:09). A close up shot of the farm houses show they are crudely erected structures reminiscent of the middle ages (5:28). Corn fields dissipate and the countryside becomes hilly and wooded (6:03). Finland is known as the land of a thousand lakes, though it should be known as the land of 60,000 lakes (6:11). The route continues on for 300 miles until hitting another agricultural district (6:44) sprinkled with one-story windmills. It continues around the Gulf of Bothnia (6:54). The only important town along the way is Oluu where the Oulujoki River cuts the city into three (7:28). Uneven cobblestone roads (7:38) and wooden buildings with elaborate ornate facades. Rivers float timber out from the forests (8:18). Finland’s timber industry racks in 80 million pounds annually (8:28). The timber is sent to sawmills along the coast (9:35). Stacks along the road await trucks (9:40). A car heads to be taken across a river by ferry as bridges become less frequent (10:27). The pulley system is operated by the ferryman, his young daughter and by the passengers (10:45). The government auctioned the ferries to those who would operate them at the lowest cost (11:02). Further on, another farm area appears with small white wooden churches (11:33). Most of the water for homes are sourced by well (11:49). The road then re-enters the wilderness (12:03). A sign with “Arctic Circle” in four different languages (12:05) follows as the road crosses the imaginary line marking the Arctic circle. Cattle are wandering through the road (12:31), hay farms (13:08), and stacks of wood to heat the homes in the winter (13:24). A housewife washes her clothes using water from a brook (13:32). The road hits Lapland (13:54) and turns into a dirt road (14:01). Reindeer feed on the lichen in winter (15:05). A log hut has reindeer antlers placed on top (15:22). Laplanders with their colorful handcrafted headdresses and pointed toe tall boots (15:43). Vegetation becomes stunted while approaching the northern coastline (16:29). The film wraps up as the road reaches the deep-water port of Liinakhamari (16:40).

This film is part of the Periscope Film LLC archive, one of the largest historic military, transportation, and aviation stock footage collections in the USA. Entirely film backed, this material is available for licensing in 24p HD, 2k and 4k. For more information visit http://www.PeriscopeFilm.com

QotD: British military incompetence

There is much in England that this explains. It explains the decay of country life, due to the keeping-up of a sham feudalism which drives the more spirited workers off the land. It explains the immobility of the public schools, which have barely altered since the ‘eighties of the last century. It explains the military incompetence which has again and again startled the world. Since the ‘fifties every war in which England has engaged has started off with a series of disasters, after which the situation has been saved by people comparatively low in the social scale. The higher commanders, drawn from the aristocracy, could never prepare for modern war, because in order to do so they would have had to admit to themselves that the world was changing. They have always clung to obsolete methods and weapons, because they inevitably saw each war as a repetition of the last. Before the Boer War they prepared for the Zulu War, before the 1914 for the Boer War, and before the present war for 1914. Even at this moment hundreds of thousands of men in England are being trained with the bayonet, a weapon entirely useless except for opening tins. It is worth noticing that the navy and, latterly, the Air Force, have always been more efficient than the regular army. But the navy is only partially, and the Air Force hardly at all, within the ruling-class orbit.

It must be admitted that so long as things were peaceful the methods of the British ruling class served them well enough. Their own people manifestly tolerated them. However unjustly England might be organized, it was at any rate not torn by class warfare or haunted by secret police. The Empire was peaceful as no area of comparable size has ever been. Throughout its vast extent, nearly a quarter of the earth, there were fewer armed men than would be found necessary by a minor Balkan state. As people to live under, and looking at them merely from a liberal, negative standpoint, the British ruling class had their points. They were preferable to the truly modern men, the Nazis and Fascists. But it had long been obvious that they would be helpless against any serious attack from the outside.

George Orwell, “The Lion And The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius”, 1941-02-19.