An interesting notion on how people innovate or invent is discussed in Anton Howes’ latest Age of Invention newsletter:

… my research on the Industrial Revolution has yielded a general model of how to think about it.

Core to the model is the observation that innovation spreads from person to person. It is a mentality, that we pick up from others. Of my sample of inventors, active c.1550-1850, the vast majority of them had had some kind of contact with an inventor before inventing anything themselves. So far, I’ve found evidence of that contact for about 83% of them, and for the remainder we frankly know next to nothing about them anyway. On the balance of probability, I suspect that all inventors had and continue to have such prior contact, even if the evidence has been lost to the mists of time.

Supposing I’m right about this — and there’s also more recent evidence from the largest and most detailed ever study of modern American inventors to support it — then such exposure to an inventor is the ultimate cause of innovation. Everything else we worry about when promoting innovation, from funding to intellectual property rights, or from education to social acceptance, is in a sense downstream of it.

Absent any exposure to inventors, people simply don’t become inventors. Knowing about invention as an activity is a necessary precondition to becoming an inventor yourself. The vast majority of people never innovate, for the very simple reason that it never occurs to them to do so. People are faced with problems all the time, but they generally have all sorts of pre-existing responses to them. Famine? The millennia-old response was to tighten belts or starve. Not to try to innovate with agricultural techniques. Trade route collapse? The millennia-old response was to take the hit, or try to shift to other familiar markets. Not to try to send ships into the icy unknown. As I’ve noticed time and time and time again, necessity is not the mother of invention. It only appears that way in retrospect — it’s when faced with a crisis that pre-existing inventors step forth to solve problems in ways they had already been investigating. Without them, there would be no such innovative response. Crises have an effect on the direction of invention — that is, on what problems people identify and then try to solve — but not on its underlying supply.

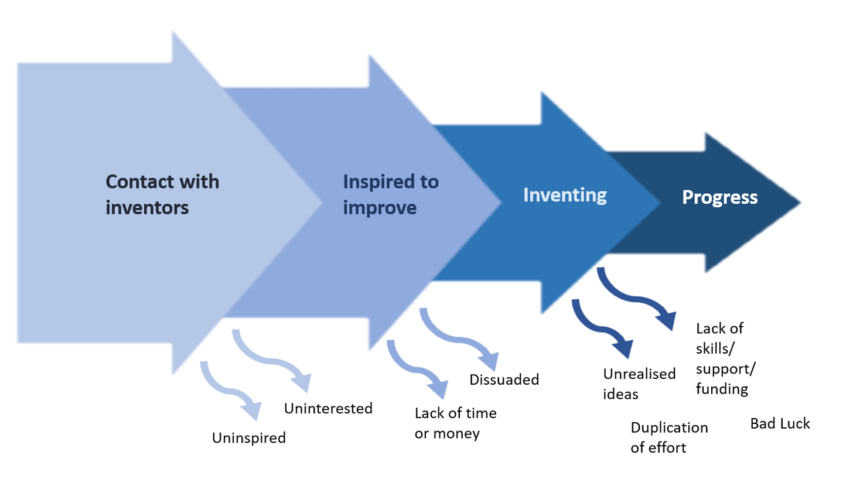

But this is not to say that exposure to an inventor is sufficient. Supposing you do meet an inventor. Your contact might be too fleeting to have an impact, or you might not be predisposed to be inspired by them. You might lack curiosity, or be distracted by some other preoccupation. Or perhaps the inventor you met might not be an especially inspiring person. Some people are simply more interesting than others. So from an initial spring of people who come into contact with inventors, we can immediately narrow the flow of new inventors down to those for whom such exposure actually had an impact.

But we then have to narrow it down further. Of the people who have met an inventor and been inspired by them, some might be distracted by other activities, or be dissuaded by social barriers, or lack the resources to tinker around with things, whether it be money or time.