Almost all of our hard data on race comes from sociology programs in universities – ie the most liberal departments in the most liberal institutions in the country. Most of these sociology departments have an explicit mission statement of existing to fight racism. Many sociologists studying race will tell you quite openly that they went into the field – which is not especially high-paying or prestigious – in order to help crusade against the evil of racism.

Imagine a Pfizer laboratory whose mission statement was to prove Pfizer drugs had no side effects, and whose staff all went into pharmacology specifically to help crusade against the evil of believing Pfizer’s drugs have side effects. Imagine that this laboratory hands you their study showing that the latest Pfizer drug has zero side effects, c’mon, trust us! Is there any way you’re taking that drug?

We know that a lot of medical research, especially medical research by drug companies, turns up the wrong answer simply through the file-drawer effect. That is, studies that turn up an exciting result everyone wants to hear get published, and studies that turn up a disappointing result don’t – either because the scientist never submits it to the journals, or because the journal doesn’t want to publish it. If this happens all the time in medical research despite growing safeguards to prevent it, how often do you think it happens in sociological research?

Do you think the average sociologist selects the study design most likely to turn up evidence of racist beliefs being correct, or the study design most likely to turn up the opposite? If despite her best efforts a study does turn up evidence of racist beliefs being correct, do you think she’s going to submit it to a major journal with her name on it for everyone to see? And if by some bizarre chance she does submit it, do you think the International Journal Of We Hate Racism So We Publish Studies Proving How Dumb Racists Are is going to cheerfully include it in their next edition?

And so when people triumphantly say “Modern science has completely disproven racism, there’s not a shred of evidence in support of it”, we should consider that exactly the same level of proof as the guy from 1900 who said “Modern science has completely proven racism, there’s not a shred of evidence against it”. The field is still just made of people pushing their own dogmatic opinions and calling them science; only the dogma has changed.

And although Reactionaries love to talk about race, in the end race is nothing more than a particularly strong and obvious taboo. There are taboos in history, too, and in economics, and in political science, and although they’re less obvious and interesting they still mean you need this same skepticism when parsing results from these fields. “But every legitimate scientist disagrees with this particular Reactionary belief!” should be said with the same intonation as “But every legitimate archbishop disagrees with this particular heresy.”

This is not intended as a proof that racism is correct, or even as the slightest shred of evidence for that hypothesis (although a lot of Reactionaries are, in fact, racist as heck). No doubt the Spanish Inquisition found a couple of real Satanists, and probably some genuine murderers and rapists got sent to Siberia. Sometimes, once in a blue moon, a government will even censor an idea that happens to be false. But it’s still useful to know when something is being censored, so you don’t actually think the absence of evidence for one side of the story is evidence of anything other than people on that side being smart enough to keep their mouths shut.

Scott Alexander, “Reactionary Philosophy In An Enormous, Planet-Sized Nutshell”, Slate Star Codex, 2013-03-03.

November 21, 2015

QotD: Investigating the reactionary view of racism

November 20, 2015

The Forgotten Front – World War 1 in Libya I THE GREAT WAR – Week 69

Published on 19 Nov 2015

12 war zones were not enough for this global war and this week an often forgotten theatre of war opens in Libya. Local Arab tribesmen fight against the British in guerrilla war. As if the Italians did not have enough problems at the Isonzo Front where Luigi Cardona is still sending his men into certain death against the Austrian defences. The situation for the Serbs is grim too and on the Western Front the carnage continues unchanged.

We’re in “a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad news cycle for Obamacare”

Megan McArdle on the plight of some health insurance companies as they try to offer healthcare policies and still make some sort of profit in the current American market:

… UnitedHealth abruptly said it expected to lose hundreds of millions of dollars on its exchange policies in 2015 and 2016, and would be assessing whether to pull out of the market altogether in the first half of next year.

This was part of a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad news cycle for Obamacare; as ProPublica journalist Charles Ornstein said on Twitter, “Not since 2013 have I seen such a disastrous stream of bad news headlines for Obamacare in one 24-hour stretch.” Stories included not just UnitedHealth’s dire warnings, but also updates in the ongoing saga of higher premiums, higher deductibles and smaller provider networks that have been coming out since open enrollment began.

It now looks pretty clear that insurers are having a very bad experience in these markets. The sizeable premium increases would have been even higher if insurers had not stepped up the deductibles and clamped down on provider networks. The future of Obamacare now looks like more money for less generous coverage than its architects had hoped in the first few years.

But of course, that doesn’t mean insurers need to leave the market. Insurance is priced based on expectations; if you expect to pay out more, you just raise the price. After all, people are required to buy the stuff, on pain of a hefty penalty. How hard can it be to make money in this market?

What UnitedHealth’s action suggests is that the company is not sure it can make money in this market at any price. Executives seem to be worried about our old enemy, the adverse selection death spiral, where prices go up and healthier customers drop out, which pushes insurers’ costs and customers’ prices up further, until all you’ve got is a handful of very sick people and a huge number of very expensive claims.

Some commentators, including me, worried a lot about death spirals in the early days of the disastrous exchange rollout. Some commentators, also including me, have eased off on those fears in recent years. Why the change? Because when the law was passed, I was mostly focused on whether the mandate penalty would be enough to encourage people to buy insurance. Over time, as the exchanges evolved, the subsidies, and the open enrollment limitations, started to look a lot more important than the penalty.

[…]

An earnings call like today’s can also be a bargaining tactic. Health insurers are engaged in a sort of perpetual negotiation with regulators over how much they’ll be allowed to charge, what sort of help they’ll get from the government if they lose money, and a thousand other things. Signaling that you’re willing to pull out of the market if you don’t get a better deal is a great way to improve your bargaining position with legislators and regulatory agencies.

That said, strategic positioning is obviously far from the whole story, or even the majority of it. UnitedHealth really is losing money on these policies right now. It really is seeing something that looks dangerously like adverse selection. And frankly, there’s not that much the company can get out of regulators at this point, because the Congressional Republicans have cut off the flow of funds. So while Obamacare certainly isn’t dead, or certain to spiral to its death, it’s got some very worrying symptoms.

Here’s a very disturbing economic issue

At Coyote Blog, Warren Meyer shares his concerns about the constantly increasing regulatory burden of American business:

5-10 years ago, in my small business, I spent my free time, and most of our organization’s training time, on new business initiatives (e.g. growth into new businesses, new out-warding-facing technologies for customers, etc). Over the last five years, all of my time and the organization’s free bandwidth has been spent on regulatory compliance. Obamacare alone has sucked up endless hours and hassles — and continues to do so as we work through arcane reporting requirements. But changing Federal and state OSHA requirements, changing minimum wage and other labor regulations, and numerous changes to state and local legislation have also consumed an inordinate amount of our time. We spent over a year in trial and error just trying to work out how to comply with California meal break law, with each successive approach we took challenged in some court case, forcing us to start over. For next year, we are working to figure out how to comply with the 2015 Obama mandate that all of our salaried managers now have to punch a time clock and get paid hourly.

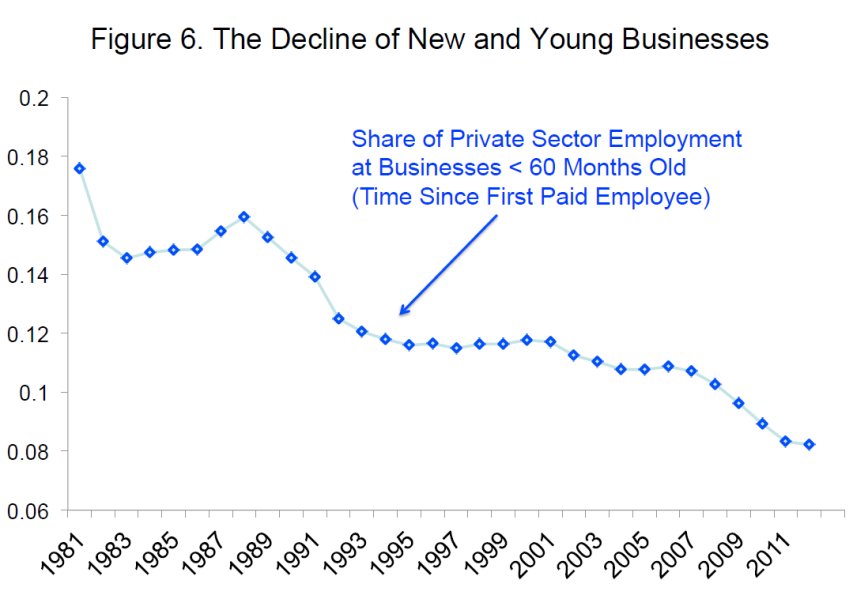

Greg Mankiw points to a nice talk on this topic by Steven Davis. For years I have been saying that one effect of all this regulation is to essentially increase the minimum viable size of any business, because of the fixed compliance costs. A corollary to this rising minimum size hypothesis is that the rate of new business formation is likely dropping, since more and more capital is needed just to overcome the compliance costs before one reaches this rising minimum viable size. The author has a nice chart on this point, which is actually pretty scary. This is probably the best single chart I have seen to illustrate the rise of the corporate state:

Canada’s dubious gains from the TPP

Michael Geist gives an overview of the pretty much complete failure of Canadian negotiators to salvage anything from the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement:

The official release of the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), a global trade agreement between 12 countries including Canada, the United States, and Japan, has sparked a heated public debate over the merits of the deal. Leading the opposition is Research in Motion founder Jim Balsillie, who has described the TPP as one of Canada’s worst-ever policy moves that could cost the country billions of dollars.

My weekly technology law column […] notes that as Canadians assess the 6,000 page agreement, the implications for digital policies such as copyright and privacy should command considerable attention. On those fronts, the agreement appears to be a major failure. Canadian negotiators adopted a defensive strategy by seeking to maintain existing national laws and doing little to extend Canadian policies to other countries. The result is a deal that the U.S. has rightly promoted as “Made in America.” [a video of my recent talk on this issue can be found here].

In fact, even the attempts to preserve Canadian law were unsuccessful. The TPP will require several important changes to domestic copyright rules including an extension in the term of copyright that will keep works out of the public domain for an additional 20 years. New Zealand, which faces a similar requirement, has estimated that the extension alone will cost its economy NZ$55 million per year. The Canadian cost is undoubtedly far higher.

In addition to term extension, Canada is required to add new criminal provisions to its digital lock rules and to provide the U.S. with confidential reports every six months on efforts to stop the entry of counterfeit products into the country.

QotD: Rolling Stone

… Rolling Stone morphed into AARP Magazine so slowly, I hardly even noticed.

Ed Driscoll, “Plutocrat Millionaires Insult Military Veterans”, PJ Media, 2014-11-14.

November 19, 2015

Is a possible cure for old age now in sight?

Matt Ridley on recent developments in the search for ways to ameliorate the effects of aging:

Squeezed between falling birth rates and better healthcare, the world population is getting rapidly older. Learning how to deal with that is one of the great challenges of this century. The World Health Organisation has just produced a report on the implications of an ageing population, which — inadvertently — reveals a dismal fatalism we share about the illnesses of old age: that they will always be inevitable.

This could soon be wrong. A new book, The Telomerase Revolution, published in America this week by the doctor and medical researcher Michael Fossel, argues that we now understand enough about the fundamental cause of ageing to be confident that we will eventually be able to reverse it. This would mean curing diseases such as Alzheimer’s, heart disease and osteoporosis, rather than coping with them or treating their symptoms.

Let me show you what I mean about fatalism. The WHO report on ageing and health, for all its talk of the need for “profound changes” to health care for the elderly, actually urges us to stop trying to cure the afflictions of old age and learn to live with them: “The societal response to population ageing will require a transformation of health systems that moves away from disease-based curative models and towards the provision of older-person-centred and integrated care.”

Yet it also subscribes to the somewhat magical hope that illnesses of old age can be “prevented or delayed by engaging in healthy behaviours” and that “physical activity and good nutrition can have powerful benefits for health and wellbeing.” This is largely wishful thinking. There is no evidence that, say, Alzheimer’s can be prevented by a certain diet or activity. A lack of activity and poor nutrition can worsen health at any age, but the underlying chronic diseases of old age are caused by age itself.

When I asked Dr Fossel what he thought of the WHO report, he replied: “In 1950 we could have talked (and did) about ‘active polio’ in the sense of keeping polio victims active rather than giving up, but the very phrase itself implies that one has already given up. I would prefer that we cure the fundamental problem. Why talk about ‘active ageing’, ‘successful ageing’, and ‘healthy ageing’ when we could talk about not ageing?”

The historical origins of the nation-state

“Samizdata Illuminatus” on the historical evolution of a bunch of armed thugs into a modern government:

… I was familiar with the hypothesis that the origin of the modern state has its roots in criminal enterprise, yet it is always amusing attempting to reconcile this with the modern state’s increasingly matronly efforts to get its subjects to behave themselves. And it is certainly far from an implausible theory, when you consider how similar the objectives of a criminal enterprise and a state can be. The major difference is, of course, that the state functions within the law — hardly surprising since it is the major source of law — while criminal organisations operate outside of the law. But honestly, how could the activity of a crime gang that defeated a local rival in a turf war be described as anything other than a spot of localised gun control — in terms of ends, if perhaps not means?

But the article got me thinking about what we can do and perhaps intend to do about what Sean Gabb would describe as “the ruling class” — the politicians and senior bureaucrats — but also the minor apparatchiks, too. In terms of the big picture stuff, the bolded part above resonates with me as particularly axiomatic, and if libertarians or classical liberals or small government conservatives or one of the very many labels we choose to call ourselves — if we stand for any one single thing, surely it is for the obliteration of this instinct, this scourge, from the human species. Yes, I am fully aware that previous efforts to change human nature for various ends have generally worked out appallingly, so maybe I should write about ‘disincentivising’ an instinct rather than ‘obliterating’ it. (I’m keeping ‘scourge’. Fair’s fair.) Although there are those amongst us who favour a muscular Ceaușescu solution to big government for those who believe they can spend our hard-earned better than we can, along with those willing to assist them in taking it off us and spending it. Others prefer an incremental strategy of rolling back government to the point that those who wish to “command economic resources” for a living find they enjoy slightly less demand for their services than a VCR repairman. I suspect both methods, perhaps working in concert at times, will be necessary at differing stages of the struggle against the statists if we are ever to be able to declare victory over them (and then leave them alone, as Glenn Reynolds is wont to say).

I do have a gripe about a distinction the author makes between paper-stamping, useless, make-work bureaucracy, and “public goods” bureaucracy, an example of which he doesn’t actually specify, although throughout the piece the inference is quite clear that he’s referring to schools and hospitals and the like — and presumably in the parts of schools and hospitals where service provision takes place; not where the (many) papers are pushed and stamped. Now, many here (rightly, I believe) probably object to the contention made that the market traditionally failed to provide such services of the “public good”, hence the state springing to the rescue to address this “market failure”. There are many people here — Paul Marks comes to mind — who will know a great deal more than I do about the patchwork of friendly societies and other private arrangements that individuals and their families paid into voluntarily and turned to for financial aid in times of illness, unemployment, or other trouble, as well as the nature of the education sector prior to the era of compulsory government schooling; the vast majority of which was crowded out by “free” state healthcare and education. However, my purpose is not wish to dwell on this now, interesting a topic as it is.

“Changing Canada’s copyright term … means two decades where zero historical work enters the public domain”

There may be good parts of the Trans-Pacific Partnership deal, but there are emphatically bad parts, as Jesse Schooff describes in the particular case of the arbitrary extension of copyright in Canada from fifty years to seventy years:

One of the TPP areas of scope which is critical to discuss is the section on copyright. At this point, several notable bloggers* have covered the TPP’s copyright extension provisions in great detail. But what do those provisions mean for you? Let’s bring it down to the ground. For example: folks in my demographic seem to love seeing old-timey photos of their city. Here in Vancouver, exploring our retro-downtown through old photographs of various eras is practically an official pastime.

A quality source of such photo collections is a city’s municipal archives. Traditionally, an archives’ mandate is to store physical objects and documents, which include the physical “analog” photos taken during most of the 20th century. “Great!” someone might say, “the archives can just digitize those photos and put them up on their website, right?”

Let’s ignore the fact that the solution my strawperson proposes has a host of logistical issues attached, not the least of which is the thousands of work-hours required to digitize physical materials. Our focus is copyright — just because the archives has the original, physical photo in their collection doesn’t mean that they own the rights to it.

You have to remember that our newfangled, internet-enabled society is relatively new. When I was a child, if a person wanted to see a historical photo from a city archives, they would actually have to physically GO to said archives and ask an archivist to retrieve the appropriate fonds containing the photo. Journalists and other professionals likely did this regularly, but for the most part, the public at large didn’t usually head down to a municipal building and ask an archivist to search through their collection just to look at a few old photos.

Today, things are much different. If a municipal archives has digitized a significant portion of, say, their collection of 19th and 20th century historical photos, then those photos can be curated online; made accessible to the public at large for everyone to access, learn from, and enjoy!

[…]

Some of the photos, we’ll call them “Group A”, were explicitly released into the public domain by the photographer, so those are okay to use. Another bunch, “Group B”, are photos whose photographer died more than fifty years ago (1965 and before); any copyright on these photos is expired. Some “Group C” photos were commissioned by a businesses, or the rights were specifically sold to a corporation, which means that the archives will have to get permission or pay a fee to make them available online. Most frustrating is the big “Group D”, whose authorship/ownership is sadly ambiguous, for various reasons**. It would be risky for the archives to include the Group D photos in their collection, since they might be violating the copyright of the original author.

So already, knowing and managing the tangle of copyright laws is a huge part of curating these event photos. Hang on, because the TPP is here to make it even worse.

It’s been long-known that the United States is very set on a worldwide-standard copyright term of seventy years from the death of the author. Sadly, such a provision made it into the TPP. Worse still, a release by New Zealand’s government indicates that this change could be retroactive, meaning that those photos in my hypothetical “Group B” would be yanked out of the public domain and put back under copyright.

Korea: Admiral Yi – III: The Bright Moonlight of Hansando – Extra History

Published on 10 Oct 2015

While Yi found success at sea, the Korean land army suffered terrible losses. Yi Il, the man who once accused Yi of negligence, lost one battle after another, until finally the regular forces were annihilated at Chungju. The Joseon court that ruled to Korea fled to Pyongyang, on the verge of being pushed out of their own country. But that same day, Admiral Yi tore through a Japanese fleet at Okpo. He moved on to Sacheon, where he baited the Japanese commander into a trap and debuted his turtle ship. The unstoppable turtle ship carried the day, so he used this tactic again and again he destroyed a Japanese fleet while suffering no losses of his own. Finally, Hideyoshi ordered his naval commanders to take Jeolla, Yi’s headquarters. Sadly for him, his general Wakisaka Yasaharu grew too eager and engaged Yi without backup at Gyeonnaeryang Strait, only to find himself lured into an even more sophisticated version of Yi’s bait-and-retreat strategy: a “Crane’s Wing” of ships that collapsed on the overextended target from all sides. In one of the largest naval battles in history, Yi scored a decisive win and again didn’t lose a single ship. He headed to Angolpo to attack Hideyoshi’s two remaining generals and seal his victory, but they refused to be baited. He had to settle for a long range exchange of cannon fire, which worked at the cost of many injuries to his own men. In the end, he destroyed all but a few Japanese ships, and those he only spared to give the Japanese some means to escape and stop raiding in Korea. But he had accomplished his goal: Hideyoshi ordered a halt to all naval operations except guarding Busan, and without this control of the sea, Japan could not re-supply their troops nor hope to resume the assault that would have finally pushed Korea’s leaders out of Korea.

November 18, 2015

Adam Smith – The Inventor of Market Economy I THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Published on 22 Feb 2015

Adam Smith was one of the first men who explored economic connections in England and made clear, in a time when Mercantilism reigned, that the demands of the market should determine the economy and not the state. In his books Smith was a strong advocator of the free market economy. Today we give you the biography of the man behind the classic economic liberalism and how his ideas would change the world forever.

A maple-flavoured world’s first?

On the Mercatus Centre site, Laura Jones points out an unexpected Canadian first:

Canada recently became the first country in the world to legislate a cap on regulation. The Red Tape Reduction Act, which became law on April 23, 2015, requires the federal government to eliminate at least one regulation for every new one introduced. Remarkably, the legislation received near-unanimous support across the political spectrum: 245 votes in favor of the bill and 1 opposed. This policy development has not gone unnoticed outside Canada’s borders.

Canada’s federal government has captured headlines, but its approach was borrowed from the province of British Columbia (BC) where controlling red tape has been a priority for more than a decade. BC’s regulatory reform dates back to 2001 when a newly elected government put in place policies to make good on its ambitious election promise to reduce the regulatory burden by one-third in three years. The results have been impressive. The government has reduced regulatory requirements by 43 percent relative to when the initiative started. During this time period, the province went from being one of the poorest-performing economies in the country to being among the best. While there were other factors at play in the BC’s economic turnaround, members of the business community widely credit red tape reduction with playing a critical role.

The British Columbia model, while certainly not perfect, is among the most promising examples of regulatory reform in North America. It offers valuable lessons for US governments interested in tackling the important challenge of keeping regulations reasonable. The basics of the BC model are not complicated: political leadership, measurement, and a hard cap on regulatory activity.

This paper describes British Columbia’s reforms, evaluates their effectiveness, and offers practical “lessons learned” to governments interested in the elusive goal of regulatory reform capable of making a lasting difference. It also offers some important lessons for business groups and think tanks outside government that are pushing to reduce red tape. These groups can make all the difference in framing the issue in such a way that it can gain wide support from policymakers. A brief discussion of the challenges of accurately defining and quantifying regulation and red tape add context to understanding the BC model, and more broadly, some of the challenges associated with effective exercises in cutting red tape.

While I’m a huge fan of reducing the regulatory burden in theory, I can’t help but expect to be disappointed about the implementation in reality… (however, should the federal bureaucracy somehow manage to perform nearly as well as the BC experiment, it’ll be Justin Trudeau getting the credit for it, rather than Stephen Harper — but better that the country benefits as a whole rather than the former PM gets boasting rights.)

The Trudeau legacy

At Gods of the Copybook Headings, Richard Anderson isn’t impressed with the PM, who he refers to as “our selfie Prime Minister”, and contrasts him with his father:

Canada is a bubble nation. We have so long been at peace, so long been rich and free, that much of the world beyond our borders is akin to another planet. The working assumption of the Canadian Left — Justin very much included — is that Islamist terrorism is the product of some grave misunderstanding. If only we were to constructively engage with those who oppose us peace would be at hand. All we need is a chance for dialogue and our graduate school acquired “conflict resolution skills” would restore humanity and decency. This is among the gravest misconceptions of our age.

Trudeau the Elder considered both the FLQ and the PQ threats to Canada’s survival. Yet his response to each was radically different. Terrorism was beyond the bounds of legitimate democratic discourse. Force must be met with force. He explained this with great care in his speech justifying the invocation of the War Measures Act. It shows a statesman — however deeply flawed in other areas of public policy — fighting to sustain a democratic government against violent usurpation. The speech is also a stark and sobering contrast to his son’s juvenile pronouncements.

Yet PET took a very different approach in dealing with democratic separatism. The PQ — however obnoxious and cynical — was a legitimate democratic force. When the Pequistes formed their first majority government in 1976 the response from Ottawa was to argue, cajole and bribe. The usual instruments of a democratic state. It would have been thought absurd and utterly unCanadian to have dispatched federal troops to arrest Rene Levesque and his cadre of petty ethnic nationalists.

Pierre Trudeau could only occasionally distinguish between bad and outright evil. He could crush the FLQ and then saunter off to Cuba to play sing-a-long with a mass murdering tyrant. Though at least at that point in history Fidel Castro was hardly a threat to world peace. Trudeau’s 1976 trip was a morally repugnant though not a dangerous act.

Islamist fanatics are very much a threat to the peace of France, Canada and the world. In his first test as an international leader Justin has shown a dangerous inability to differentiate between bad and evil. Since Canada is a smaller player in a big world that might not matter very much in the short-term. Yet sooner or later this evil will come to Canada and the man charged with our defence has shown himself to be pathetically inadequate to the challenge.

ESR on “Hieratic documentation”

Eric S. Raymond explains how technical documentation can manage the difficult task of being both demonstrably complete and technically correct and yet totally fail to meet the needs of the real audience:

I was using “hieratic” in a sense like this:

hieratic, adj. Of computer documentation, impenetrable because the author never sees outside his own intimate knowledge of the subject and is therefore unable to identify or meet the expository needs of newcomers. It might as well be written in hieroglyphics.

Hieratic documentation can be all of complete, correct, and nearly useless at the same time. I think we need this word to distinguish subtle disasters like the waf book – or most of the NTP documentation before I got at it – from the more obvious disasters of documentation that is incorrect, incomplete, or poorly written simply considered as expository prose.