Published on 26 Nov 2015

Far away from the Western Front, the British Indian Army gets intro trouble in Mesopotamia against the Ottoman Empire. In the Alps, the Fourth Battle of the Isonzo is proving just as disastrous to the Italians the other three before. And in Serbia the situation is getting darker and darker as Nis is falling to the Central Powers. All while the flying aces of World War 1 are fighting it out in the skies over the Western Front.

November 27, 2015

Pride Comes Before The Fall – British Trouble in Mesopotamia I THE GREAT WAR – Week 70

Wealth, inequality, and billionaires

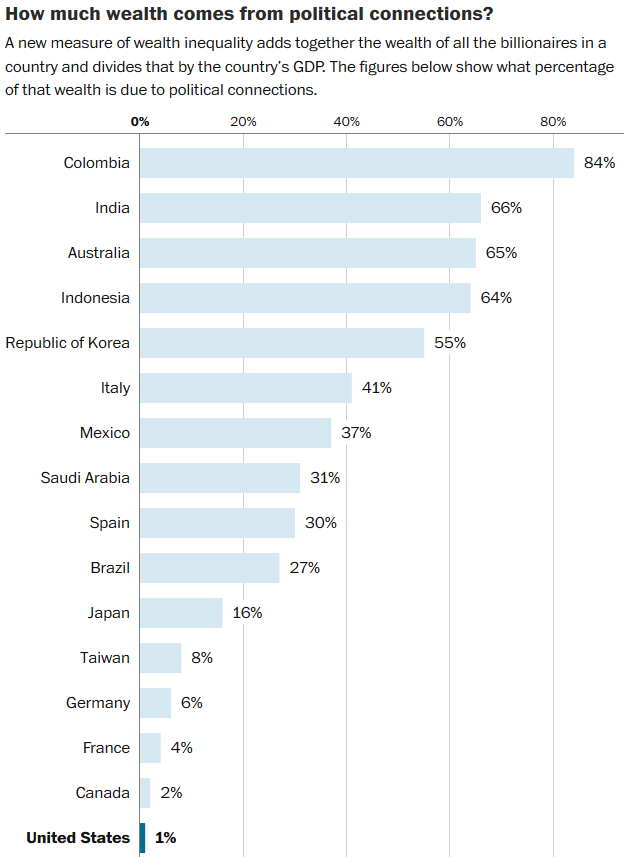

Several months ago, the Washington Post reported on a new study of wealth and inequality that tracked how many billionaires got rich through competition in the market and how many got rich through political “connections”:

The researchers found that wealth inequality was growing over time: Wealth inequality increased in 17 of the 23 countries they measured between 1987 and 2002, and fell in only six, Bagchi says. They also found that their measure of wealth inequality corresponded with a negative effect on economic growth. In other words, the higher the proportion of billionaire wealth in a country, the slower that country’s growth. In contrast, they found that income inequality and poverty had little effect on growth.

The most fascinating finding came from the next step in their research, when they looked at the connection between wealth, growth and political connections.

The researchers argue that past studies have looked at the level of inequality in a country, but not why inequality occurs — whether it’s a product of structural inequality, like political power or racism, or simply a product of some people or companies faring better than others in the market. For example, Indonesia and the United Kingdom actually score similarly on a common measure of inequality called the Gini coefficient, say the authors. Yet clearly the political and business environments in those countries are very different.

So Bagchi and Svejnar carefully went through the lists of all the Forbes billionaires, and divided them into those who had acquired their wealth due to political connections, and those who had not. This is kind of a slippery slope — almost all billionaires have probably benefited from government connections at one time or another. But the researchers used a very conservative standard for classifying people as politically connected, only assigning billionaires to this group when it was clear that their wealth was a product of government connections. Just benefiting from a government that was pro-business, like those in Singapore and Hong Kong, wasn’t enough. Rather, the researchers were looking for a situation like Indonesia under Suharto, where political connections were usually needed to secure import licenses, or Russia in the mid-1990s, when some state employees made fortunes overnight as the state privatized assets.

The researchers found that some countries had a much higher proportion of billionaire wealth that was due to political connections than others did. As the graph below, which ranks only countries that appeared in all four of the Forbes billionaire lists they analyzed, shows, Colombia, India, Australia and Indonesia ranked high on the list, while the U.S. and U.K. ranked very low.

Looking at all the data, the researchers found that Russia, Argentina, Colombia, Malaysia, India, Australia, Indonesia, Thailand, South Korea and Italy had relatively more politically connected wealth. Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland and the U.K. all had zero politically connected billionaires. The U.S. also had very low levels of politically connected wealth inequality, falling just outside the top 10 at number 11.

When the researchers compared these figures to economic growth, the findings were clear: These politically connected billionaires weighed on economic growth. In fact, wealth inequality that came from political connections was responsible for nearly all the negative effect on economic growth that the researchers had observed from wealth inequality overall. Wealth inequality that wasn’t due to political connections, income inequality and poverty all had little effect on growth.

The Balance of Industries and Creative Destruction

Published on 18 Mar 2015

Why are price signals and market competition so important to a market economy? When prices accurately signal costs and benefits and markets are competitive, the Invisible Hand ensures that costs are minimized and production is maximized. If these conditions aren’t met, market inefficiencies arise and the Invisible Hand cannot do its work. In this video, we show how two major processes, creative destruction and the elimination principle, work with the Invisible Hand to create a competitive marketplace that works for producers and consumers.

A different view of Uber and other ride-sharing services

Robert Tracinski on Uber as a form of “Objectivist LARP“:

If it sometimes seems like it’s impossible to restore the free market, as if every new wave of government regulation is irreversible, then consider that one form of regulation, which is common in the most dogmatically big-government enclaves in the country, is being pretty much completely dismantled before our eyes. And it’s the hippest thing ever.

I was reminded of this by a recent report about yet another attempt to help traditional taxis compete with “ride-sharing” services like Uber and Lyft: a new app called Arro, which allows you to both hail a traditional taxi and pay for it from your phone. So Arro takes a twentieth-century business and finally drags into the twenty-first century. This certainly might help improve the taxi experience relative to how things were done before. But it won’t fend off Uber and Lyft, because it doesn’t change the central issues, which are political rather than technological.

[…]

Uber has been hit with complaints that it’s running “an Objectivist LARP,” a live-action role playing of a capitalist utopia from an Ayn Rand novel. That’s pretty much what it is doing, and the results are awesome. And the benefits don’t stop with more drivers and lower rates. Uber is ploughing a fair portion of its profits into another wave of technological innovation—self-driving cars—that promises to offer even greater improvements in the future.

All of this should counter some of the despair about how to promote free markets, especially among urban elites who have been programmed by their college educations to embrace the rhetoric of the Left. Give them half a chance, and they will flock to capitalist innovations run according to the laws of the market.

The problem is that they don’t want to admit it. That’s where the euphemism “ride-sharing” comes in. To cover up the capitalistic nature of the activity, they tell themselves they’re “sharing” something that they are quite obviously paying for, and paying at market rates. Imagine what could be accomplished if they were just willing to drop the euphemisms and embrace the free market.

QotD: The myth of the “permanent majority”

Many Republicans seem confident that last week’s performance in the mid-term elections bodes the end of the Obama era, and the dawn of the bright Republican future. Many Democrats seem confident that last week’s performance in the midterms was a mere blip on the way to the Emerging Democratic Majority. Both sides would do well to read Sean Trende’s 2012 book, The Lost Majority, which I made my way through this weekend.

To state Trende’s thesis simply: There is no such thing as a permanent majority. Parties are coalitions of disparate groups of voters, and they win by strapping enough different groups together to push themselves across the electoral finish line. Unfortunately, the broader your coalition, the harder it is to hold together. Those different groups may have radically different values and interests; satisfying one may end up alienating the other. Trende suggests that the longest-lived coalition was not, in fact Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s famed “realignment,” which showed large cracks as early as 1937, but the Eisenhower coalition that lasted roughly from 1952 to 1988. As the dates suggest, the reason for unity was the external threat from the Soviet Union. That’s a pretty stiff price to pay for internal unity.

I took two major things away from the book: First, you can’t count on demographics to hand you a victory in such a vast and diverse country, because today’s coalition members may end up as a large and growing pillar of the opposition. And second, although both parties are constantly hunting for a mandate for radical change, the voters almost never deliver one. The party stalwarts may want to tear down the current edifice and start over, but the less ideological coalition partners are usually looking for some light redecorating, perhaps along with a specific personal interest like freedom of conscience in business operations, or less restrictive immigration policy. The harder the parties push on their ideological platforms, the faster the “coalition of everyone” starts leaking supporters to the opposition.

Megan McArdle, “No Party Will Get a Permanent Majority”, Bloomberg View, 2014-11-10.