New York just killed every economist’s favorite thing about Uber: surge pricing. Sure, many economists also love convenient car service at the touch of a button. But black-car services have been around for a long time. Explicit surge pricing — which both creates new supply and rations demand — has not, but it’s long been a core feature of Uber Technologies Inc.’s business model. While it can be annoying at times (during a recent rainstorm, I noticed a sudden epidemic of drivers canceling rides, which I suspect was due to the rapidly rising surge price), it also allows you to be sure that you will be able to get a taxi on New Year’s Eve or during a rainstorm as long as you’re willing to pay extra.

Sadly, no one else loves surge pricing as much as economists do. Instead of getting all excited about the subtle, elegant machinery of price discovery, people get all outraged about “price gouging.” No matter how earnestly economists and their fellow travelers explain that this is irrational madness — that price gouging actually makes everyone better off by ensuring greater supply and allocating the supply to (approximately) those with the greatest demand — the rest of the country continues to view marking up generators after a hurricane, or similar maneuvers, as a pretty serious moral crime.

Megan McArdle, “Uber Makes Economists Sad”, Bloomberg View, 2014-07-09.

June 24, 2015

QotD: Surge pricing

June 23, 2015

A Genius and A Madman – Fritz Haber I WHO DID WHAT IN WW1?

Published on 22 Jun 2015

Fritz Haber is one of the most famous German scientists. His inventions made it possible to feed an ever growing human population and influence us till this day. But Fritz Haber had a dark side too: His research made the weaponization of gas and the increased production of explosives possible. Find out more about the life of Fritz Haber in our biography.

Richard Blake reviews ten films set in the Roman empire

Wandering a bit off his usual (Byzantine empire) era, Richard Blake looks at how Hollywood has portrayed Rome in film:

My purpose in this article is to describe and compare and judge ten films set in the Roman Empire. I will apply two criteria. The first, and most obvious, is how these films stand as works of art in their own right — narrative structure, acting, general production values and so forth. The second, and for me almost equally important, is how well they show that the Ancients lived in a moral universe fundamentally different from our own.

Now, for the avoidance of doubt, I will say at once that I have no time for any of the neo-Marxist claims about Antiquity. Karl Polanyi and Moses Finlay were wrong in their belief that the laws of supply and demand have only operated since the eighteenth century. Michel Foucault was more than usually wrong when he denied that the Ancients had any notion of the individual. In all times and places, human nature is the same. All people are motivated by some combination of sex, money, status, power and the fear of death. The laws of Economics apply just as well in Ancient Rome as they do in Modern England.

What I do mean, however, is that these basic motivations showed themselves in often radically different ways. The Ancients were not Christians. They were not universalists. They had no concept of human equality. The establishment of chattel slavery among them normalised attitudes and behaviour that would have been thought outrageous in Ancien Régime Europe, and that every religious denomination would have been mobilised to denounce in the ante bellum American South.

The Ancients lacked technologies and scientific and moral concepts that we have taken for granted for five or six or even eight centuries. A modern secularist has more in common with a twelfth century theologian than with a Greek rationalist. He probably has more in common with a sixth century Bishop than with a pagan philosopher.

One of the main, though seldom noticed, differences between virtually everyone in the past and us is that they lived under the continual shadow of death. I have reached the age of fifty five. I might fall dead tomorrow, but the insurance tables tell me I have a long way yet to go before I need to start thinking hard about the inevitable end of things. I put off begetting children until I was in my forties. I only took up a serious study of the piano last year. Catullus was dead at thirty, Horace and Vergil in their fifties. Constantine the Great was an old and dying man when he was younger than I am now. Shorter time horizons must have an effect on almost every approach to life.

Any fictional recreation must show these differences, and show them without vexing readers or viewers with endless asides. I try to show them in my series of thrillers set in seventh century Byzantium. Without more elaboration, let me see how well they are shown in the ten films I have selected.

“Being skunked” takes on a new meaning

At Defence One, Patrick Tucker looks at an “improved” stink bomb now available to American police departments:

As protestors and police officers clash on the streets of Baltimore and other divided cities, some police departments are stockpiling a highly controversial weapon to control civil unrest.

It’s called Skunk, a type of “malodorant,” or in plainer language, a foul-smelling liquid. Technically nontoxic but incredibly disgusting, it has been described as a cross between “dead animal and human excrement.” Untreated, the smell lingers for weeks.

The Israeli Defense Forces developed Skunk in 2008 as a crowd-control weapon for use against Palestinians. Now Mistral, a company out of Bethesda, Md., says they are providing it to police departments in the United States.

Skunk is composed of a combination of baking soda and amino acids, Mistral general manager Stephen Rust said at the National Defense Industrial Association’s Armament Systems Forum on April 20. “You can drink it, but you wouldn’t want to,” said Rust, a retired U.S. Army project manager.

The Israelis first used it in 2008 to disperse Palestinians protesting in the West Bank. A BBC video shows its first use in action, sprayed by a hose, a system that has come to be known as the “crap cannon.”

QotD: The Physician

Hygiene is the corruption of medicine by morality. It is impossible to find a hygienist who does not debase his theory of the healthful with a theory of the virtuous. The whole hygienic art, indeed, resolves itself into an ethical exhortation, and, in the sub-department of sex, into a puerile and belated advocacy of asceticism. This brings it, at the end, into diametrical conflict with medicine proper. The aim of medicine is surely not to make men virtuous; it is to safeguard and rescue them from the consequences of their vices. The true physician does not preach repentance; he offers absolution.

H.L. Mencken, “Types of Men 5: The Physician”, Prejudices, Third Series, 1922.

June 22, 2015

“Because economic growth is a dead end. The greens present the only way out”

J.R. Ireland pokes fun at the UK Green Party manifesto for the last general election:

All around the world our cultures might be different, our languages might be different, and we may think differently and act differently, but there is one fact which is true in every country on the face of planet Earth: The local Green Party will always be completely and irredeemably insane. From Australian pundit Tim Blair I’ve been made aware of the manifesto for the United Kingdom Green Party, a ludicrous amalgamation of wishful thinking, happy talk, and a total unwillingness to consider the unintended consequences of their proposed policies. From the absolutely bugfuck bonkers Youth Manifesto:

Because economic growth is a dead end. The greens present the only way out.

Vote Green because they’re the only party courageous enough to promise voters that they will end economic growth. If there’s one way to win elections, it’s to tell the good people of Britain that you promise them an eternity of poverty and absolutely guarantee they will never get any richer.

Furthermore:

We would introduce the right to vote at 16 because we believe that young people should have a say, as proven by the Scottish Independence Referendum in 2014.

Indeed. Who wouldn’t want to have their country governed by the preferred candidates of middle teenagers? Why, the average 16 year old is so incredibly knowledgeable about the world and completely understands such complex topics as economics, immigration, and that hot chick Kristy’s red panties that he accidentally saw when she was uncrossing her legs in homeroom. With those sorts of brilliant minds choosing the leaders of the future, what could possibly go wrong?

[…]

But the real crazy, the high-end crazy, the crazy with a ribbon on top was saved not for their youth manifesto but for the manifesto allegedly meant for the big boys and girls who have hit puberty biologically, even if they never quite made it intellectually. The Green Party, you see, promises to give you infinite happiness without any negative consequences whatsoever:

Imagine having a secure, fulfilling and decently paid job, knowing that you are working to live and not living to work. Imagine coming home to an affordable flat or house, and being valued for your contribution and character, not for how much you earn. Imagine knowing that you and your friends are part of an economy that works with the planet rather than against it. Imagine food banks going out of business. Imagine the end of poverty and deprivation. The key to all this is to put the economy at the service of people and planet rather than the other way round. That’s what the Green Party will do.

Imagine there’s no countries. It isn’t hard to do. Nothing to kill or die for and no religion too.

Indeed. Now if only John Lennon lyrics were a governing philosophy, by Jove the Greens might be onto something! Unfortunately for the Green Party, our actions often have consequences we could not have foreseen and, unsurprisingly, if you declare war on business with massive taxes, anti-trade legislation and the nationalization of banks and the housing industry, it’s awfully difficult to ‘end poverty and deprivation’ since you’ve completely eliminated the way by which people have the opportunity to lift themselves up. But don’t worry — the Greens will just sprinkle some fairy dust around and negative consequences will magically be done away with! Supply and demand is simply a filthy conspiracy perpetuated by the bourgeoisie!

Breaking – it’s a nation-wide crime wave (when you cherry-pick your data)

Daniel Bier looks at how Wall Street Journal contributor Heather Mac Donald concocted her data to prove that there’s a rising tide of crime across the United States:

Heather Mac Donald is back in the Wall Street Journal to defend her thesis that there is a huge national crime wave and that protesters and police reformers are to blame.

In her original piece, Mac Donald cherry picked whatever cities and whatever categories of crime showed an increase so far this year, stacked up all the statistics that supported her idea, ignored all the ones that didn’t, and concluded we are suffering a “nationwide crime wave.”

Of course, you could do this kind of thing any year to claim that crime is rising. But it isn’t.

The fifteen largest cities have seen a 2% net decrease in murder so far this year. Eight saw a rise in murder rates, and seven saw an even larger decline.

Guess which cities Mac Donald mentioned and which she did not.

This is how you play tennis without the net. Or lines.

And in her recent post, buried seven paragraphs in, comes this admission: “It is true that violent crime has not skyrocketed in every American city — but my article didn’t say it had.”

But neither did her article acknowledge that murder in big cities was falling overall — in fact, it didn’t acknowledge that murder or violent crime was declining anywhere. Apparently, in her view, it is acceptable to present a distorted view of the data as long as it isn’t an outright lie.

Are software APIs covered by copyright?

At Techdirt, Mike Masnick looks at a recent Supreme Court case that asks that very question:

The Obama administration made a really dangerous and ignorant argument to the Supreme Court yesterday, which could have an insanely damaging impact on innovation — and it appears to be because Solicitor General Donald Verrilli (yes, the MPAA’s old top lawyer) is absolutely clueless about some rather basic concepts concerning programming. That the government would file such an ignorant brief with the Supreme Court is profoundly embarrassing. It makes such basic technological and legal errors that it may be the epitome of government malfeasance in a legal issue.

We’ve written a few times about the important copyright question at the heart of the Oracle v. Google case (which started as a side show to the rest of the case): are software APIs covered by copyright. What’s kind of amazing is that the way you think about this issue seems to turn on a simple question: do you actually understand how programming and software work or not? If you don’t understand, then you think it’s obvious that APIs are covered by copyright. If you do understand, you recognize that APIs are more or less a recipe — instructions on how to connect — and thus you recognize how incredibly stupid it would be to claim that’s covered by copyright. Just as stupid as claiming that the layout of a program’s pulldown menus can be covered by copyright.

The judge in the district court, William Alsup, actually learned to code Java to help him better understand the issues. And then wrote such a detailed ruling on the issue that it seemed obvious that he was writing it for the judges who’d be handling the appeal, rather than for the parties in the case.

An insurance scam that targets the most vulnerable

At The Intercept, Juan Thompson talks about a burgeoning insurance scam that not only rips off the victims for their insurance premiums but then makes it worse through police action:

Martin was taken in by a widening scam in which crooks, posing as auto insurance agents, prey on working people struggling to find affordable policies. Under the scam, the perpetrator offers auto insurance for a low price — low because the scammer, posing as a broker, will buy an authentic policy using fraudulent means of payment, keeping the policy just long enough to collect a proof of insurance card.

The racket is a growing problem in New York City and South Florida, according to an insurance industry group, but seems most prevalent in Michigan, where premiums are inflated by a state mandate that drivers purchase insurance plans that have unlimited lifetime medical benefits, among other features. Victims in Michigan are thrown even deeper into crisis when police, as is common there, accuse victims of being in on the scam and seize their vehicles and other assets under civil forfeiture laws.

The scam and seizures show how crooks and cops can end up working in concert to further imperil those already on the economic brink. Indeed, in this case, low-income residents are pinched at every turn. They start off with especially high insurance premiums, consumer advocates argue, because insurance companies sometimes charge people in low-income communities more for auto insurance in a practice some have labeled modern redlining.

Bogus agents exploit the need for cheaper policies by selling insurance that’s too good to be true, leaving victims financially exposed, for example, in the case of an accident. As if all that weren’t enough, the police then turn on the victims of the fraud, who are far easier to track down than the original perpetrators.

“You have a blend of crooked agents selling innocent, squeezed drivers bogus policies and insurance cards, and high insurance premiums,” said James Quiggle of the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud, a group that receives funding from insurance companies.

QotD: Obesity

The most maddening example of this is, of course, the case of thin people, or folks who could really stand to lose ten pounds, lecturing the obese on how stupid they are for letting themselves get fat. […]

As a friend who really struggles with his weight points out, the author seems not to understand that for people with a weight problem, weight loss often involves both: you’re tired and miserable and overweight, and also, you’re spending a huge amount of mental energy counting calories and making time for exercise.

Moreover, this really underplays the amount of mental energy we’re talking about. When you talk to people who have successfully lost really large amounts of weight as adults — amounts that bring them from the really risky “super-obese” category into something more normal — you find two things. First, that most of them don’t keep it off, unless they have bariatric surgery, in which case, 50 percent of them keep it off. And second, that the people who are keeping the weight off without surgery are going to extreme lengths to maintain their weight loss, lengths that most of us would probably find difficult to fit into our lives: weighing every ounce of food they consume, counting calories obsessively, exercising for long periods every day, and constantly battling “intrusive thoughts of food.”

It’s not quite fair to say that most of the public health experts I’ve seen talking about obesity are thin people brightly telling fat people that “Everything would be fine if you’d just be more like me!” But it’s not really that far off the mark, either. In the words of another friend who struggled with his weight, and got quite testy when I suggested weight loss was easy, “You’ve hit the pick six in the genetic lottery, and you think you earned it.”

Megan McArdle, “Dinner, With a Side of Self-Righteousness”, Bloomberg View, 2015-03-27.

June 21, 2015

“… the carbon tax, like Paris, is worth a Mass”

At National Review the editors’ response to the Pope’s encyclical on climate change is not warm:

There is an undeniable majesty to the papacy, one that is politically useful to the Left from time to time. The same Western liberals who abominate the Catholic Church as an atavistic relic of more superstitious times, who regard its teachings on abortion and contraception as inhumane and its teachings on sexuality as a hate crime today are celebrating Pope Francis’s global-warming encyclical, Laudato Si’, as a moral mandate for their cause. So much for that seamless garment.

It may be that the carbon tax, like Paris, is worth a Mass.

The main argument of the encyclical will be no surprise to those familiar with Pope Francis’s characteristic line of thought, which combines an admirable and proper concern for the condition of the world’s poor with a crude and backward understanding of economics and politics both. Any number of straw men go up in flames in this rhetorical auto-da-fé, as the pope frames his concern in tendentious economic terms: “By itself, the market cannot guarantee integral human development and social inclusion.” We are familiar with no free-market thinker, even the most extreme, who believes that “by itself, the market can guarantee integral human development.” There are any number of other players in social life — the family, civil society, the large and durable institution of which the pope is the chief executive — that contribute to human flourishing. The pope is here taking a side in a conflict that, so far as we can tell, does not exist.

“Why libertarianism is closer to Stalinism than you think” … unless you actually know anything about libertarianism, of course

Alan Wolfe, I’m reliably informed, is a highly respected sociologist and political scientist at Boston College. If this kind of thing is typical of his output, I’m inclined to doubt my sources:

“Libertarianism has a complicated history, and it is by and large a sordid one,” charges Wolfe. It is “a secular substitute for religion, complete with its own conception of the city of God, a utopia of pure laissez-faire and the city of man, a place where envy and short-sightedness hinder creative geniuses from carrying out their visions.”

I’d call him the Hitler of Hyperbole, but that seems, I don’t know, a tad over the top. Sort of like equating a live-and-let-live philosophy such as libertarianism to Stalinism. Which I confess it totally is. Except for the gulags, the mass murders, the forced relocations, the belief in statism, a demonstrably insane economic policy — I’m probably forgetting one or two other points of similarity.

Predictably, Wolfe disinters the corpse of Ayn Rand and insists not only was the Atlas Shrugged author “an authoritarian at heart” but that she remains the beating heart of an intellectual, philosophical, and cultural movement that includes a fistful of Nobel Prize winners (Friedman, Buchanan, Smith, Hayek, Vargas Llosa, etc.); thinkers such as Robert Nozick and Camille Paglia; businessmen such as Whole Foods’ John Mackey, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Overstock’s Patrick Byrne; and creative types ranging from Rose Wilder Lane to the creators of South Park to Vince Vaughn. Sound the alarum, folks! Team America: World Police and Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story are running on Comedy Central again!

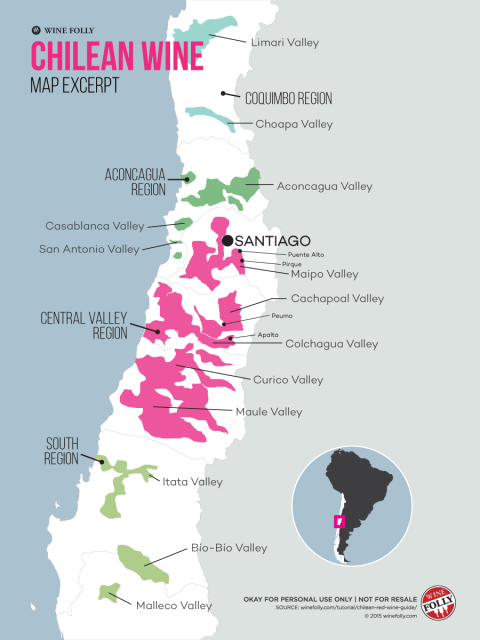

Chile’s red wine regions

Chile has emerged over the last decade or so as a dependable source of relatively inexpensive — and good value — red wine. Here is Wine Folly‘s brief overview of the distinctive wine regions of Chile:

It seems unlikely that the thin, long country of Chile is a larger producer of Cabernet Sauvignon than the US, but it’s true!

Chile’s vineyard area dedicated to Cabernet Sauvignon is second only to France. The country has become a winemaking hot spot due to the cooling effect Chile receives from the Pacific Ocean and the Humboldt Current. In other words, Chile has an ideal climate for wine. Chilean red wines have gone from good to exceptional in recent years and yet, they still offer good value.

Most of Chile’s vineyards are located in the Central Valley Region, which is a large region that contains several smaller valleys including Maipo, Colchagua and Maule Valley. Most of the Central Valley is wide and flat and this is where the bulk of Chilean wine is made. If you’re looking for age-worthy wine however, the fine wines of Chile tend to be found in the foothills (areas with higher elevations), especially the sub-regions of Puente Alto (in Alto Maipo or “High Maipo”) and Alto Cachapoal (“High Cachapoal”). Chilean Cabernet Sauvignon and Bordeaux blends have a signature tart-and-fruity style, typical of a cool-climate wine. The tartness (aka acidity) comes from cool ocean breezes being pulled inland by the incredibly tall Andes Mountains.

QotD: Getting into trouble in Imperial Germany

All three of us, by some means or another, managed, between Nuremberg and the Black Forest, to get into trouble.

Harris led off at Stuttgart by insulting an official. Stuttgart is a charming town, clean and bright, a smaller Dresden. It has the additional attraction of containing little that one need to go out of one’s way to see: a medium-sized picture gallery, a small museum of antiquities, and half a palace, and you are through with the entire thing and can enjoy yourself. Harris did not know it was an official he was insulting. He took it for a fireman (it looked like a fireman), and he called it a “dummer Esel.”

In German you are not permitted to call an official a “silly ass,” but undoubtedly this particular man was one. What had happened was this: Harris in the Stadgarten, anxious to get out, and seeing a gate open before him, had stepped over a wire into the street. Harris maintains he never saw it, but undoubtedly there was hanging to the wire a notice, “Durchgang Verboten!” The man, who was standing near the gates stopped Harris, and pointed out to him this notice. Harris thanked him, and passed on. The man came after him, and explained that treatment of the matter in such off-hand way could not be allowed; what was necessary to put the business right was that Harris should step back over the wire into the garden. Harris pointed out to the man that the notice said “going through forbidden,” and that, therefore, by re-entering the garden that way he would be infringing the law a second time. The man saw this for himself, and suggested that to get over the difficulty Harris should go back into the garden by the proper entrance, which was round the corner, and afterwards immediately come out again by the same gate. Then it was that Harris called the man a silly ass. That delayed us a day, and cost Harris forty marks.

I followed suit at Carlsruhe, by stealing a bicycle. I did not mean to steal the bicycle; I was merely trying to be useful. The train was on the point of starting when I noticed, as I thought, Harris’s bicycle still in the goods van. No one was about to help me. I jumped into the van and hauled it out, only just in time. Wheeling it down the platform in triumph, I came across Harris’s bicycle, standing against a wall behind some milk-cans. The bicycle I had secured was not Harris’s, but some other man’s.

It was an awkward situation. In England, I should have gone to the stationmaster and explained my mistake. But in Germany they are not content with your explaining a little matter of this sort to one man: they take you round and get you to explain it to about half a dozen; and if any one of the half dozen happens not to be handy, or not to have time just then to listen to you, they have a habit of leaving you over for the night to finish your explanation the next morning. I thought I would just put the thing out of sight, and then, without making any fuss or show, take a short walk. I found a wood shed, which seemed just the very place, and was wheeling the bicycle into it when, unfortunately, a red-hatted railway official, with the airs of a retired field-marshal, caught sight of me and came up. He said:

“What are you doing with that bicycle?”

I said: “I am going to put it in this wood shed out of the way.” I tried to convey by my tone that I was performing a kind and thoughtful action, for which the railway officials ought to thank me; but he was unresponsive.

“Is it your bicycle?” he said.

“Well, not exactly,” I replied.

“Whose is it?” he asked, quite sharply.

“I can’t tell you,” I answered. “I don’t know whose bicycle it is.”

“Where did you get it from?” was his next question. There was a suspiciousness about his tone that was almost insulting.

“I got it,” I answered, with as much calm dignity as at the moment I could assume, “out of the train.”

“The fact is,” I continued, frankly, “I have made a mistake.”

He did not allow me time to finish. He merely said he thought so too, and blew a whistle.

Recollection of the subsequent proceedings is not, so far as I am concerned, amusing. By a miracle of good luck — they say Providence watches over certain of us — the incident happened in Carlsruhe, where I possess a German friend, an official of some importance. Upon what would have been my fate had the station not been at Carlsruhe, or had my friend been from home, I do not care to dwell; as it was I got off, as the saying is, by the skin of my teeth. I should like to add that I left Carlsruhe without a stain upon my character, but that would not be the truth. My going scot free is regarded in police circles there to this day as a grave miscarriage of justice.

But all lesser sin sinks into insignificance beside the lawlessness of George. The bicycle incident had thrown us all into confusion, with the result that we lost George altogether. It transpired subsequently that he was waiting for us outside the police court; but this at the time we did not know. We thought, maybe, he had gone on to Baden by himself; and anxious to get away from Carlsruhe, and not, perhaps, thinking out things too clearly, we jumped into the next train that came up and proceeded thither. When George, tired of waiting, returned to the station, he found us gone and he found his luggage gone. Harris had his ticket; I was acting as banker to the party, so that he had in his pocket only some small change. Excusing himself upon these grounds, he thereupon commenced deliberately a career of crime that, reading it later, as set forth baldly in the official summons, made the hair of Harris and myself almost to stand on end.

German travelling, it may be explained, is somewhat complicated. You buy a ticket at the station you start from for the place you want to go to. You might think this would enable you to get there, but it does not. When your train comes up, you attempt to swarm into it; but the guard magnificently waves you away. Where are your credentials? You show him your ticket. He explains to you that by itself that is of no service whatever; you have only taken the first step towards travelling; you must go back to the booking-office and get in addition what is called a “schnellzug ticket.” With this you return, thinking your troubles over. You are allowed to get in, so far so good. But you must not sit down anywhere, and you must not stand still, and you must not wander about. You must take another ticket, this time what is called a “platz ticket,” which entitles you to a place for a certain distance.

What a man could do who persisted in taking nothing but the one ticket, I have often wondered. Would he be entitled to run behind the train on the six-foot way? Or could he stick a label on himself and get into the goods van? Again, what could be done with the man who, having taken his schnellzug ticket, obstinately refused, or had not the money to take a platz ticket: would they let him lie in the umbrella rack, or allow him to hang himself out of the window?

To return to George, he had just sufficient money to take a third-class slow train ticket to Baden, and that was all. To avoid the inquisitiveness of the guard, he waited till the train was moving, and then jumped in.

That was his first sin:

(a) Entering a train in motion;

(b) After being warned not to do so by an official.

Second sin:

(a) Travelling in train of superior class to that for which ticket was held.

(b) Refusing to pay difference when demanded by an official. (George says he did not “refuse”; he simply told the man he had not got it.)

Third sin:

(a) Travelling in carriage of superior class to that for which ticket was held.

(b) Refusing to pay difference when demanded by an official. (Again George disputes the accuracy of the report. He turned his pockets out, and offered the man all he had, which was about eightpence in German money. He offered to go into a third class, but there was no third class. He offered to go into the goods van, but they would not hear of it.)

Fourth sin:

(a) Occupying seat, and not paying for same.

(b) Loitering about corridor. (As they would not let him sit down without paying, and as he could not pay, it was difficult to see what else he could do.)

But explanations are held as no excuse in Germany; and his journey from Carlsruhe to Baden was one of the most expensive perhaps on record.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men on the Bummel, 1914.