Published on 3 Feb 2015

What’s the difference between a wage subsidy and a minimum wage? What is the cost of a wage subsidy to taxpayers? We take a look at the earned income tax credit and how it affects low-skilled workers. We also discuss Nobel Prize-winning economist Edmund Phelps’ work on wage subsidies.

May 25, 2015

Wage Subsidies

Women in combat roles

At War on the Rocks, Anna Simons looks at the ongoing controversy in the United States over allowing women to serve in front-line combat roles:

Earlier this year, I spoke with a roomful of field grade officers about the debate and controversy over women in combat. The officers knew my position. What was next to impossible for me to discern, however, was where most of them are when it comes to this topic — which is the challenge with trying to have an open debate about it. The topic is just too politically charged for opponents to feel they can speak openly or honestly.

Officers who balk at the idea of women serving in ground infantry units or on Special Forces Operational Detachments Alpha (ODAs) won’t publicly say so, let alone publicly explain why. They worry about retaliation that could hurt their careers. In contrast, those who have no reservations — usually because they won’t be the ones who have to deal with the fallout from integration at the small unit level — slough off the challenge as just another minor problem or “ankle biter.”

There is more to this dichotomy than just officers’ career concerns, however. As one member of the audience put it, even if special operations forces and Marine Corps brass are prepared to go to Capitol Hill armed with irrefutable logic and unimpeachable facts against integrating women into ground combat units, they will still come across as chauvinists. For any male who opposes full integration, the chauvinist charge is impossible to escape.

I am sure there is something to this; and if I were a male, the chauvinism charge might mortally wound me as well. Maybe knowing in advance that this is how I would be branded would cause me to fight only on grounds of proponents’ choosing. For example, I could use standards and measurable data — as if there is some scientific way to determine what the right ratios and formulae are to prevent anything untoward happening when young men and women are put together in the field for indeterminate lengths of time.

QotD: Deflation

Deflation occurs when there is not enough currency in circulation to meet the needs of the economy. Here again, the classical definition focuses on falling prices rather than an insufficient currency stock, but deflation is primarily a monetary phenomenon.

It is the economic version of anemia: too little blood is reaching the body. Each unit of the currency goes up in value relative to the goods and services available, but because the stock of currency isn’t growing fast enough, it starves the economy of investment capital. There isn’t enough money to build out existing business, to create new ones, or to hire new workers. (This is in part what happened during the Great Depression of the 1930’s.) Inventories shrink, but new goods aren’t being produced due to the lack of investment capital. Eventually the economy grinds to a halt as production withers away.

Specie currencies are more prone to deflation than fiat currencies for the simple reason that fiat currencies are not based on scarce (and thus valuable) resources like gold, silver, or what have you. There’s only so much gold and silver to go around, and sometimes the supply of bullion can be interrupted for long periods. (Sometimes this is even done deliberately by rival nations or speculators.) Also, because the value of gold and silver is set outside the control of government or authority issuing the currency, it limits the kinds of monetary policy the sovereign can conduct, especially during times of crisis.

Monty, “Inflation, Deflation, and Monetary Policy”, Ace of Spades HQ, 2014-07-11.

May 24, 2015

Charles Stross proposes “The Evil Business Plan of Evil”

Well, “proposes” isn’t quite the right word:

Let me describe first the requirements for the Evil Business Plan of Evil, and then the Plan Itself, in all it’s oppressive horror and glory.

Some aspects of modern life look like necessary evils at first, until you realize that some asshole has managed to (a) make it compulsory, and (b) use it for rent-seeking. The goal of this business is to identify a niche that is already mandatory, and where a supply chain exists (that is: someone provides goods or service, and as many people as possible have to use them), then figure out a way to colonize it as a monopolistic intermediary with rent-raising power and the force of law behind it. Sort of like the Post Office, if the Post Office had gotten into the email business in the 1970s and charged postage on SMTP transactions and had made running a private postal service illegal to protect their monopoly.

Here’s a better example: speed cameras.

We all know that driving at excessive speed drastically increases the severity of injuries, damage, and deaths resulting from traffic accidents. We also know that employing cops to run speed traps the old-fashioned way, with painted lines and a stop-watch, is very labour-intensive. Therefore, at first glance the modern GATSO or automated speed camera looks like a really good idea. Sitting beside British roads they’re mostly painted bright yellow so you can see them coming, and they’re emplaced where there’s a particular speed-related accident problem, to deter idiots from behaviour likely to kill or injure other people.

However, the idea has legs. Speed cameras go mobile, and can be camouflaged inside vans. Some UK police forces use these to deter drivers from speeding past school gates, where the speed limit typically drops to 20mph (because the difference in outcome between hitting a child at 20mph to hitting them at 30mph is drastic and life-changing at best: one probably causes bruises and contusions, the other breaks bones and often kills). And some towns have been accused of using speed cameras as “revenue enhancement devices”, positioning them not to deter bad behaviour but to maximize the revenue from penalty notices by surprising drivers.

This idea maxed out in the US, where the police force of Waldo in South Florida was disbanded after a state investigation into ticketing practices; half the town’s revenue was coming from speed violations. (Of course: Florida.) US 301 and Highway 24 pass through the Waldo city limits; the town applied a very low speed limit to a short stretch of these high-speed roads, and cleaned up.

Here’s the commercial outcome of trying to reduce road deaths due to speeding: speed limits are pretty much mandatory worldwide. Demand for tools to deter speeders is therefore pretty much global. Selling speed cameras is an example of supplying government demand; selling radar detectors or SatNav maps with updated speed trap locations is similarly a consumer-side way of cleaning up.

And here’s a zinger of a second point: within 30 years at most, possibly a lot sooner, this will be a dead business sector. Tumbleweeds and ghost town dead. Self-driving cars will stick to the speed limit because of manufacturer fears over product liability lawsuits, and speed limits may be changed to reflect the reliability of robots over inattentive humans (self-driving cars don’t check their Facebook page while changing lanes). These industry sectors come and go.

Mitchell’s First Theorem of Government

Dan Mitchell clearly understands what modern western government is really all about:

The John Coltrane Quartet My Favorite Things Belgium, 1965

QotD: Impressions of Dresden

We reached Dresden on the Wednesday evening, and stayed there over the Sunday.

Taking one consideration with another, Dresden, perhaps, is the most attractive town in Germany; but it is a place to be lived in for a while rather than visited. Its museums and galleries, its palaces and gardens, its beautiful and historically rich environment, provide pleasure for a winter, but bewilder for a week. It has not the gaiety of Paris or Vienna, which quickly palls; its charms are more solidly German, and more lasting. It is the Mecca of the musician. For five shillings, in Dresden, you can purchase a stall at the opera house, together, unfortunately, with a strong disinclination ever again to take the trouble of sitting out a performance in any English, French, or, American opera house.

The chief scandal of Dresden still centres round August the Strong, “the Man of Sin,” as Carlyle always called him, who is popularly reputed to have cursed Europe with over a thousand children. Castles where he imprisoned this discarded mistress or that — one of them, who persisted in her claim to a better title, for forty years, it is said, poor lady! The narrow rooms where she ate her heart out and died are still shown. Chateaux, shameful for this deed of infamy or that, lie scattered round the neighbourhood like bones about a battlefield; and most of your guide’s stories are such as the “young person” educated in Germany had best not hear. His life-sized portrait hangs in the fine Zwinger, which he built as an arena for his wild beast fights when the people grew tired of them in the market-place; a beetle-browed, frankly animal man, but with the culture and taste that so often wait upon animalism. Modern Dresden undoubtedly owes much to him.

But what the stranger in Dresden stares at most is, perhaps, its electric trams. These huge vehicles flash through the streets at from ten to twenty miles an hour, taking curves and corners after the manner of an Irish car driver. Everybody travels by them, excepting only officers in uniform, who must not. Ladies in evening dress, going to ball or opera, porters with their baskets, sit side by side. They are all-important in the streets, and everything and everybody makes haste to get out of their way. If you do not get out of their way, and you still happen to be alive when picked up, then on your recovery you are fined for having been in their way. This teaches you to be wary of them.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men on the Bummel, 1914.

May 23, 2015

The rise of the Donair

I first experienced a donair in Halifax in the summer of 1982. I won’t claim it was a life-changing experience, but it was a revelation that “street meat” didn’t have to be awful. At The Walrus, Omar Mouallem explains how the humble donair is on the verge of conquering the streets of Alberta:

Like shawarma and gyros, donairs are a meaty delicacy shaved from a rotisserie spit and wrapped in pitas — only spicier and sweeter. If you require further explanation, then you’re from neither the Maritimes (where they were invented, in the 1970s) nor Alberta (where they’re most consumed). Topped with a sweet, creamy sauce, they are a Canadian take on tzatziki-coated beef and lamb gyros, which themselves are a Greco-American take on centuries-old Turkish rotisserie lamb (a dish that also spawned a blander German variant called döner kebab). Adding to the cultural confusion, most donair operations are run by Lebanese immigrants such as Tawachi — or my father, Ahmed Mouallem, who introduced Athena’s product to my hometown of High Prairie, Alberta, in 1995. The town of 2,666 now supports four different restaurants that serve the food, but only three traffic lights.

[…]

No one, including John Kamoulakos, who with his brother Peter invented the street food in Halifax, is quite sure how donairs migrated from east to west. Aaron Tingley of Tony’s Meats (based in Antigonish, Nova Scotia), a supplier that purchased the Mr. Donair trademark and recipe from Kamoulakos in 2005, thinks Maritime labourers might have driven Alberta’s demand: “They want to experience a taste of home.”

That’s what Chawki El-Homeira was thinking in 1978, when he left Halifax to chase the Alberta oil patch. Only he was going to feed the workforce. The sixty-seven-year-old remembers his first encounter with the donair, in March 1976, as if it were yesterday. He’d arrived in Nova Scotia from Lebanon with neither family nor English and got a job washing dishes in a restaurant that served the delicacy. “Something attracted me to it,” he tells me. “It was close to our food: it’s pita bread and spicy, quality beef, like shawarma. I thought, someday I’m going to open my own donair shop.”

After watching Maritimers migrate to Fort McMurray, he packed his bags and followed. The timing was terrible. The oil patch dried up in 1980, before he could secure a lease (like a true Albertan, he blames Pierre Trudeau’s National Energy Program). So he drove a cab instead, first in Fort Mac, then in Edmonton, looking for commercial vacancies while the meter ran.

On a fellow cabbie’s tip, he purchased a submarine-sandwich shop on Whyte Avenue in 1982 (the same year Tawachi opened his) and introduced his Dartmouth recipe to Albertans one slice at a time, offering customers free samples. Word spread of “Charles Smart Donair” (his anglicized name and a poorly translated Arabic adjective), and soon he had a monopoly as a supplier to other Lebanese shop owners. Then his best customer tried to copy his technique and, he claims, sabotage his business by spreading rumours to his predominantly Muslim clientele that he, a Christian, spiked his product with pork.

If anyone knows of a good donair place in Toronto’s financial district, feel free to drop a hint in the comments…

Debunking the “GM killed the streetcars” conspiracy theory

There are many railfans who still believe, strongly and passionately, that General Motors was involved in a devious plot to kill off the streetcars across North America in order to sell more buses. At Vox.com, Joseph Stromberg explains that this wasn’t the case — in fact, the killer of the streetcar/interurban/radial railway systems was their willingness to lock in to long-term uneconomic agreements with local governments in exchange for monopoly privileges:

Back in the 1920s, most American city-dwellers took public transportation to work every day.

There were 17,000 miles of streetcar lines across the country, running through virtually every major American city. That included cities we don’t think of as hubs for mass transit today: Atlanta, Raleigh, and Los Angeles.

Nowadays, by contrast, just 5 percent or so of workers commute via public transit, and they’re disproportionately clustered in a handful of dense cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago. Just a handful of cities still have extensive streetcar systems — and several others are now spending millions trying to build new, smaller ones.

So whatever happened to all those streetcars?

“There’s this widespread conspiracy theory that the streetcars were bought up by a company National City Lines, which was effectively controlled by GM, so that they could be torn up and converted into bus lines,” says Peter Norton, a historian at the University of Virginia and author of Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City.

But that’s not actually the full story, he says. “By the time National City Lines was buying up these streetcar companies, they were already in bankruptcy.”

Surprisingly, though, streetcars didn’t solely go bankrupt because people chose cars over rail. The real reasons for the streetcar’s demise are much less nefarious than a GM-driven conspiracy — they include gridlock and city rules that kept fares artificially low — but they’re fascinating in their own right, and if you’re a transit fan, they’re even more frustrating.

This is one of the reasons I’m generally against new plans to re-introduce streetcars (or their modern incarnations generally grouped under the term “light rail”), because they fail to address one of the key reasons that the old street railway/interurban/radial systems died: they were sharing road space with private vehicles. Light rail can provide a useful urban transportation option if they have their own right-of-way, but not if they are merely adding to the gridlock of already overcrowded city streets.

And once again, I’m not anti-rail … I founded a railway historical society and I commute most work days on a heavy rail commuter network. I don’t hold this position due to some anti-rail animus. If anything, I regret the passing of railway systems more than most people do, but I recognize that they have to be self-supporting (or close to self-supporting) to have a chance to survive. Being both more expensive and less convenient than alternative transportation options is a sure-fire path to extinction.

The Hitch

H/T to Open Culture.

A quick note: Kristoffer Seland Hellesmark was looking for a documentary on Christopher Hitchens to watch, but could never find one. So, after waiting a while, he said to himself, “Why don’t I just make one?” The result is the 80-minute documentary about Hitchens, lovingly entitled The Hitch, which features clips from his speeches and interviews.

QotD: The tender-minded

Unluckily for the man of tender mind, he is quite incapable of any such easy dismissal of the great plagues and conundrums of existence. It is of the essence of his character that he is too sensitive and sentimental to put them ruthlessly out of his mind: he cannot view even the crunching of a cockroach without feeling the snapping of his own ribs. And it is of the essence of his character that he is unable to escape the delusion of duty — that he can’t rid himself of the notion that, whenever he observes anything in the world that might conceivably be improved, he is commanded by God to make every effort to improve it. In brief, he is a public-spirited man, and the ideal citizen of democratic states. But Nature, it must be obvious, is opposed to democracy — and whoso goes counter to nature must expect to pay the penalty. The tender-minded man pays it by hanging forever upon the cruel hooks of hope, and by fermenting inwardly in incessant indignation. All this, perhaps, explains the notorious ill-humor of uplifters — the wowser touch that is in even the best of them. They dwell so much upon the imperfections of the universe and the weaknesses of man that they end by believing that the universe is altogether out of joint and that every man is a scoundrel and every woman a vampire. Years ago I had a combat with certain eminent reformers of the sex hygiene and vice crusading species, and got out of it a memorable illumination of their private minds. The reform these strange creatures were then advocating was directed against sins of the seventh category, and they proposed to put them down by forcing through legislation of a very harsh and fantastic kind — statutes forbidding any woman, however forbidding, to entertain a man in her apartment without the presence of a third party, statutes providing for the garish lighting of all dark places in the public parks, and so on. In the course of my debates with them I gradually jockeyed them into abandoning all of the arguments they started with, and so brought them down to their fundamental doctrine, to wit, that no woman, without the aid of the police, could be trusted to protect her virtue. I pass as a cynic in Christian circles, but this notion certainly gave me pause. And it was voiced by men who were the fathers of grown and unmarried daughters!

H.L. Mencken, “The Forward-Looker”, Prejudices, Third Series, 1922.

May 22, 2015

Przemyśl Falls Again – Winston Churchill Gets Fired I THE GREAT WAR Week 43

Published on 21 May 2015

The big success of the Gallipoli Campaign never came, thousands of soldiers died and so Winston Churchill is forced to resign. At the same time August von Mackensen is pushing back the Russians and forcing them to hide in Przemyśl fortress – the same fortress they just conquered from the Austro-Hungarians a few weeks earlier.

Reconstructing history – a population explosion in ancient Greece?

Anton Howes deserves what he gets for a blog post he titled “Highway to Hellas: avoiding the Malthusian trap in Ancient Greece”:

There’s a fantastic post by Pseudoerasmus examining the supposed ‘efflorescence’ of economic growth in Ancient Greece, and some of the causal hypotheses put forward by Josiah Ober in an upcoming book (which I’m very much looking forward to reading in full). Suffice to say, the data estimates used by Ober raise more questions than they answer.

If the constructed data is correct, then not only did Greek population grow by an extraordinary amount during the Archaic Period roughly 800-500 BC, but Greek consumption per capita grew by 50-100% from 800-300 BC. As Pseudoerasmus points out, this would imply a massive productivity gain of some 450-1000%, or 0.3-0.46% growth per annum.

This seems quite implausible to me. Indeed, the population estimates imply that the Ancient Greek population would have been substantially larger than that of Greece in the 1890s AD, along with higher agricultural productivity! This is all the more puzzling as there appears to have been no major technological change to support so many more mouths to feed, let alone feed them better than before.

But assuming the data are correct, what would have to give? Pseudoerasmus explores a number of different possibilities, such as the gains from integrating trade across the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea; or that the Greeks might have shifted agricultural production to cash crops like wine and oil and imported grain instead. None of these quite seem good enough for such a massive and prolonged escape from the Malthusian pressures of population outstripping the productivity of agriculture (although I hope the so-far unavailable chapters from Ober’s book might shed some more light on this).

A remaining explanation offered by Pseudoerasmus may, however, be the winner: that Greeks weren’t using land more intensively as Ober seems to suggest, but rather expanding the land that they brought under cultivation by colonising new areas.

Al Stewart – “Trains”

Published on 19 Mar 2013

In the sapling years of the post-war world in an English market town

I do believe we travelled in schoolboy blue, the cap upon the crown

Books on knee; our faces pressed against the dusty railway carriage panes

As all our lives went rolling on the clicking wheels of trainsThe school years passed like eternity and at last were left behind

And it seemed the city was calling me to see what I might find

Almost grown, I stood before horizons made of dreams

I think I stole a kiss or two, while rolling on the clicking wheels of trainsTrains…

All our lives were a whistle stop affair; no ties or chains

Throwing words like fireworks in the air, not much remains

A photograph in your memory, through the colored lens of time

All our lives were just a smudge of smoke against the skyThe silver rails spread far and wide through the nineteenth century

Some straight and true, some serpentine, from the cities to the sea

And out of sight of those who rode in style, there worked the military mind

On through the night to plot and chart the twisting paths of trainsOn the day they buried Jean Jaures, World War One broke free

Like an angry river overflowing its banks impatiently

While mile on mile the soldiers filled the railway stations’ arteries and veins

I see them now go laughing on the clicking wheels of trainsTrains…

Rolling off to the front across the narrow Russian gauge

Weeks turn into months and the enthusiasm wanes

Sacrifices in seas of mud, and still you don’t know why

All their lives are just a puff of smoke against the skyThen came surrender; then came the peace

Then revolution out of the east

Then came the crash; then came the tears

Then came the thirties, the nightmare years

Then came the same thing over again

Mad as the moon, that watches over the plain

Oh, driven insaneBut oh, what kind of trains are these, that I never saw before

Snatching up the refugees from the ghettoes of the war

To stand confused, with all their worldly goods, beneath the watching guards’ disdain

As young and old go rolling on the clicking wheels of trainsAnd the driver only does this job with vodka in his coat

And he turns around and he makes a sign with his hand across his throat

For days on end, through sun and snow, the destination still remains the same

For those who ride with death above the clicking wheels of trainsTrains…

What became of the innocence they had in childhood games

Painted red or blue, when I was young they all had names

Who’ll remember the ones who only rode in them to die

All their lives are just a smudge of smoke against the skyNow forty years have come and gone and I’m far away from there

And I ride the Amtrak from New York City to Philadelphia

And there’s a man to bring you food and drink

And sometimes passengers exchange a smile or two rolling on the humming wheels

But I can’t tell you if it’s them or if it’s only me

But I believe when they look outside they don’t see what I see

Over there, beyond the trees, it seems that I can just make out the stained

Fields of Poland calling out to all the passing trainsTrains…

I suppose that there’s nothing in this life remains the same

Everything is governed by the losses and the gains

Still sometimes I get caught up in the past, I can’t say why

All our lives are just a smudge of smoke, or just a breath of wind against the sky

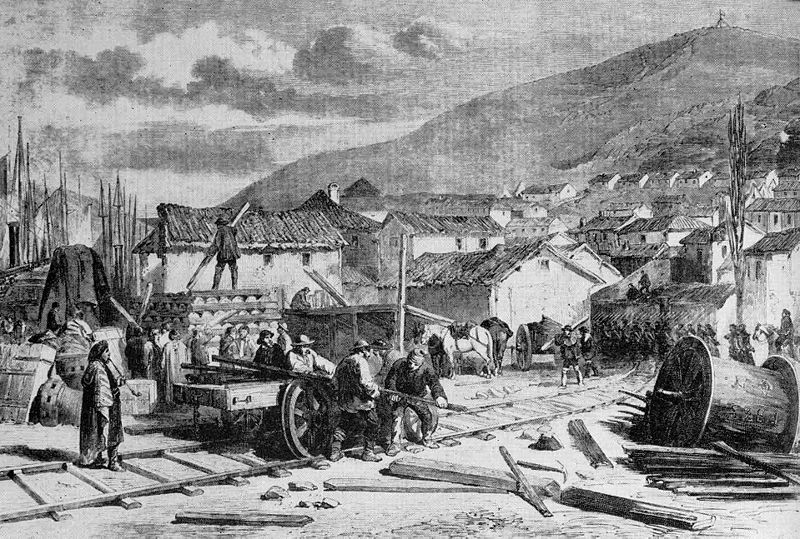

The trains of war – the military application of steam power

James Simpson on the revolution in military affairs triggered by the development of the steam engine and the railways:

Navvies working on the Grand Crimean Central Railway, 1854. Charles Walker: Thomas Brassey, Railway Builder, 1969. (via Wikipedia)

Trains were cutting-edge weapons of war in the 19th century — and all the major powers were figuring out how to deploy them. The Europeans learned how to move troops by train. The Americans — how to fight on rail cars. The British, meanwhile, found they could dominate an empire from the tracks.

In today’s world of tanks, bombers and submarines, it’s perhaps hard to believe that the train was once an amazingly mobile weapons platform. They might be locked to their rails, but for over a century trains were the fastest means of hauling troops and artillery to front lines across the world.

The invention of the railway shaped warfare for a century. Rails allowed force projection across immense distances — and at speeds which were impossible on foot or by horse.

[…]

The first demonstration of the military efficacy of the railroads was the 1846 Polish Uprising. Prussia rushed 12,000 troops of the Sixth Army Corps, with guns and horses, to the Free City of Krakow to help put down the Polish rebellion. In this period of nationalist uprisings, Russia and Austria also used their railroads against similar uprisings from 1848 to 1850.

A lack of infrastructure and experience stifled the success of these early endeavors. Due to a lack of rolling stock, suitable platforms and double-track stretches, the trains sometimes operated far slower than a man could march on foot.

Austria was first to get it right. In 1851, the Austrian Empire shuttled 145,000 men, nearly 2,000 horses, 48 artillery pieces and 464 vehicles over 187 miles.