The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 15 Sep 2018Railroads played a critical role for the United Kingdom in the Great War. But the increased burden on the nation’s railways had its cost. In the early morning hours of May 22, 1915, a crowded schedule resulted in the 1915 Quintinshill Rail Disaster, the worst railway disaster in British history. Its victims, mostly men of the 1/7 Royal Scots regiment, deserve to be remembered.

The History Guy uses media that are in the public domain. As photographs of actual events are sometimes not available, photographs of similar objects and events are used for illustration.

The episode includes historical photos involving the Great War and a 1915 railway disaster. Those photos are provided in context of the historical events. No graphic violence is shown.

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TheHistoryGuy

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered is the place to find short snippets of forgotten history from five to fifteen minutes long. If you like history too, this is the channel for you.

Awesome The History Guy merchandise is available at:

https://teespring.com/stores/the-hist…The episode is intended for educational purposes. All events are portrayed in historical context.

#quintinshill #wwi #thehistoryguy

April 23, 2020

Quintinshill, the Worst Railway Disaster in British History

April 2, 2020

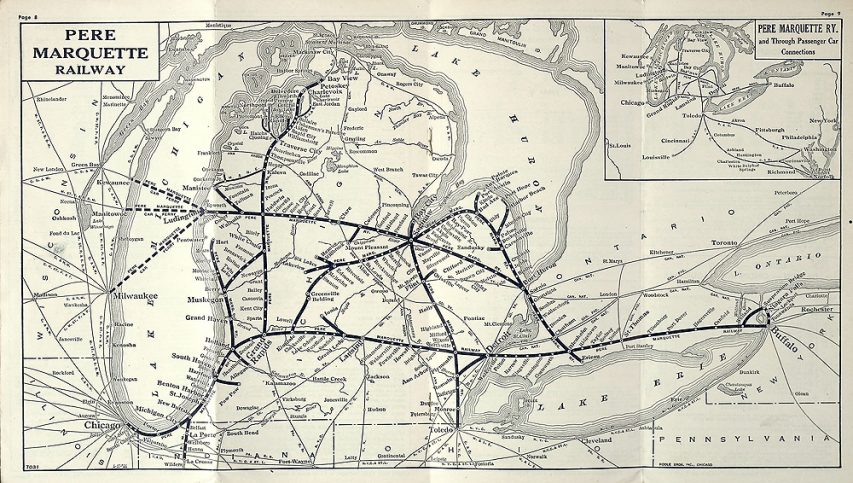

Fallen flag — the Pere Marquette Railway

This month’s fallen flag article for Classic Trains is the story of the Pere Marquette Railway by Kevin P. Keefe:

C&O’s formal acquisition of the Pere Marquette in 1947 did more than help usher in the postwar merger era; it also closed the book on a railroad with a colorful and quirky history. PM was created in 1900 by the consolidation of three roads: Flint & Pere Marquette; Detroit, Grand Rapids & Western; and Chicago & West Michigan. (The town of Pere Marquette; today we know the place as Ludington. Jacques Marquette, the French missionary and explorer, died and was buried here in 1675, and the name Pere Marquette had been given to the inlet lake off Lake Michigan, the river that feeds into it, and an 1847 community there.)

All three carriers had roots in the lumber industry, so the new Pere Marquette Railroad not only connected important Michigan cities, it also operated a branchline network covering much of the state’s Lower Peninsula. PM’s early corporate history was chaotic, marked by receivership and ownership changes. The Cincinnati, Hamilton & Dayton acquired PM in 1904 and for a time leased it to various parties, including the Erie Railroad. Thus did Baltimore & Ohio briefly control the PM through its ownership of the CH&D. When Pere Marquette came out of a receivership in 1907, it would be for only five years.

Those early, troublesome times, however, were marked by two strategic steps forward. One was the chartering of the Pere Marquette of Indiana, which built from New Buffalo, Michigan, southwest to Porter, Indiana, allowing PM to reach Chicago, via trackage rights on the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern (NYC). The second was the lease of the Lake Erie & Detroit River Railway, pushing PM eastward from Walkerville (Windsor), Ontario, to St. Thomas, thence to Suspension Bridge (Niagara Falls), New York, via rights on Michigan Central affiliate Canada Southern, and on to Buffalo on the NYC. Patched together as they were, these additions allowed PM to position itself as a Buffalo–Chicago bridge carrier.

In the ensuing years, the rectangular PM logo would largely disappear from view, although the road’s eventual 12 E7’s wore the script Pere Marquette train name, along with C&O identification, into the mid-1950s, thanks to equipment trust restrictions. PM’s three GE 70-tonners of 1947 were sold, but a few of its 16 EMD switchers (2 SW1’s of 1939 and ’42, 14 NW2’s of 1943–46) carried PM lettering into the 1960s, and C&O kept PM’s color pattern of yellow front-end bands with red pinstriping on a blue body on 11 more EMDs of 1948 that came fully lettered C&O: NW2’s 1850–1856 and E7’s 95–98.

As for the famous Berkshires, they, along with all of Pere Marquette’s steam locomotives, were retired by 1951. Eleven found a temporary reprieve on C&O’s Chesapeake District in Kentucky and West Virginia, but only for a few months. Two, 1223 and 1225, survived as display items in Michigan, and as a student at Michigan State University, I became involved with the restoration of the 1225, which today occasionally operates on excursions.

Perhaps it’s fitting that the Pere Marquette’s last equipment order as an independent railroad was in 1947 for six of EMD’s 1,500 h.p. BL2 “branchline” diesels, Nos. 80–85. Chosen to negotiate PM’s web of secondary lines — most of them rooted in the road’s origins as a logger — the homely diesels were as quirky and as singular as the PM itself. Pointedly, even though they sported the “speed striping” as found on the E7’s, the BL2’s were delivered in full “Chesapeake & Ohio” lettering.

Pere Marquette 1225, a Berkshire 2-8-4 steam locomotive, passes through Alma in March 2009.

Photo by Chelseyafoster via Wikimedia Commons.

The Pere Marquette also had a maritime division and one of their ships had a disastrous voyage (via Wikipedia) 110 years ago:

The Pere Marquette operated a number of rail car ferries on the Detroit and St. Clair Rivers and on Lake Erie and Lake Michigan. The PM’s fleet of car ferries, which operated on Lake Michigan from Ludington, Michigan to Milwaukee, Kewaunee, and Manitowoc, Wisconsin, were an important transportation link avoiding the terminal and interchange delays around the southern tip of Lake Michigan and through Chicago. Their superintendent for over 30 years was William L. Mercereau.

Pere Marquette 18

On September 10, 1910, Pere Marquette 18 was bound for Milwaukee, Wisconsin, from Ludington, Michigan, with a load of 29 railroad freight cars and 62 persons. Near midnight, the vessel began to take on massive amounts of water. The captain dumped nine railroad cars into Lake Michigan, but this was no use — the ship was going down. The Pere Marquette 17, traveling nearby, picked up the distress call and sped to assist the foundering vessel. Soon after she arrived and she could come alongside, the Pere Marquette 18 sank with the loss of 28 lives; there were 33 survivors. Her wreck has yet to be located and is the largest unlocated wreck of the Great Lakes.

November 16, 2019

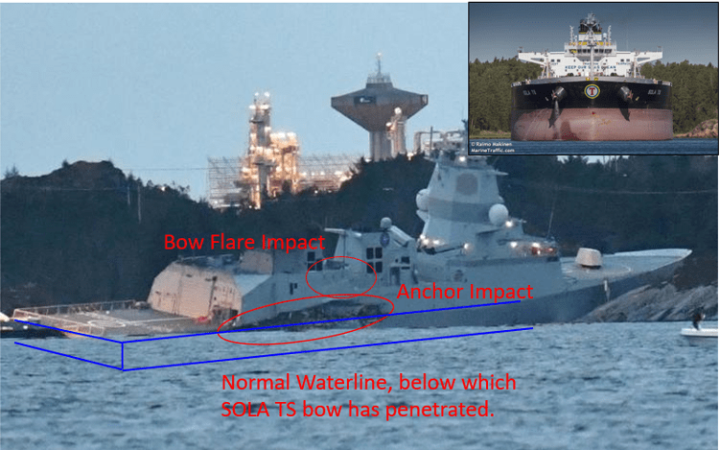

Report on the collision that sank HNoMS Helge Ingstad last year

The Norwegian frigate HNoMS Helge Ingstad was eventually declared a total loss due to the damage from the collision and the resulting water damage as the ship sank near the Sture Terminal in November 2018. The first part of the report on the accident has been released:

HNoMS Helge Ingstad, a Fridtjof Nansen-class frigate commissioned in 2009.

Photo detail via Wikimedia Commons.

The frigate HNoMS Helge Ingstad and the tanker Sola TS collided in the Hjeltefjord in the early hours of 8 November 2018. The frigate had 137 persons on board with a mix of conscripts and permanent crew. A total of seven watchstanding personnel were present on the bridge, including two trainees. The tanker Sola TS was operated by the Greek shipping company Tsakos Columbia Shipmanagement (TCM) S.A. There was a total of 24 persons on board. The bridge was manned by four persons, including the pilot.

HNoMS Helge Ingstad sailed south at a speed of approximately 17–18 knots with the automatic identification system (AIS) in passive mode, i.e. no transmission of AIS-signal. The frigate’s bridge team had notified Fedje Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) of entering the area and followed the reported voyage. Sola TS had been loaded with crude oil at the Sture Terminal, and notified Fedje VTS of departure from the terminal. Sola TS exhibited navigation lights. In addition some of the deck lights were turned on to light up the deck for the crew who were securing equipment etc. for the passage.

In advance of the collision, Fedje VTS had not followed the frigate’s passage south through the Hjeltefjord. The crew and pilot on Sola TS had observed HNoMS Helge Ingstad and tried to warn of the danger and prevent a collision. The crew on HNoMS Helge Ingstad did not realise that they were on collision course until it was too late.

At 04:01:15, HNoMS Helge Ingstad collided with the tanker Sola TS. The first point of impact was Sola TS‘ starboard anchor and the area just in front of HNoMS Helge Ingstad‘s starboard torpedo magazine.

HNoMS Helge Ingstad suffered extensive damage along the starboard side. Seven crew members sustained minor physical injuries. Sola TS received minor damages and none of the crew were injured. Marine gas oil leaked out into the Hjeltefjord. The Institute of Marine Research has ascertained the effect of the oil spill had little impact on the marine environment.

HNoMS Helge Ingstad after grounding, 13 November 2018. Due to the steep nature of the seabed at the shoreline, the frigate slid down until it was almost totally underwater after initial grounding.

Photo via The Drive.

There is an embedded video with the report that neatly summarizes the series of events leading up to the collision.

December 2, 2018

Preliminary report posted on the sinking of Norwegian frigate Helge Ingstad

The Accident Investigation Board of Norway (AIBN) and the Defense Accident Investigation Board of Norway (DAIBN) have made their initial joint report on the sinking of HNoMS Helge Ingstad available to the public:

“This report is a preliminary presentation of the AIBN’s investigations relating to the accident and does not provide a full picture,” the report warns up front. “The report may contain errors and inaccuracies.”

Based on what the investigators have determined so far, Helge Ingstad entered the fjord heading south and checked in with the Fedje Maritime Traffic Center, or Fedje VTS, at around 2:40 AM local time. Any ship over 80 feet long has to alert this control center before entering due to the narrow nature of the waterway.

The ship was traveling at approximately 20 miles per hour and had its navigation lights on. The ship’s Automatic Identification System (AIS) transponder was set to “receive only” mode, meaning that it was not transmitting its own position and other information to ships in the area.

At 3:40 AM, personnel on Helge Ingstad‘s bridge began to turn control of the ship over the next watch. At that time, the ship’s crew was aware of three northbound ships on its radar screen and had also visually observed “an object with many lights was observed lying still just outside the Sture terminal,” according to the report.

Sola did not leave the terminal until 3:45 AM. Less than 15 minutes later, the tanker’s crew radioed the Fedje VTS to inquire about a contract on their radar that was sailing with its AIS transponder apparently off.

At 4:00 AM, Fedje VTS identified the ship in question as probably Helge Ingstad and the tanker and the frigate began communicating directly. Approximately one minute later, the two ships collided.

[…]

A final report on the incident should contain more thorough explanations of exactly how the final moments of the collision played out and recommendations for the Norwegian Navy to try and prevent these sorts of accidents in the future. “So far, the AIBN has not seen any indication of technical systems not working as intended up until the time of the collision,” the report notes.

Separate from its findings regarding the events leading to the collision, the AIBN has also uncovered a serious technical issue that could have impacts well beyond this particular accident. Norwegian officials have alerted both the country’s navy and Spanish shipbuilder Navantia, which built the Helge Ingstad and Norway’s four other Fridtjof Nansen-class frigates, with concerns they have about the basic “watertight integrity” of the ships.

“The AIBN has found safety critical issues relating to the vessel’s watertight compartments,” an annex to the main report explains. “This must be assumed to also apply to the other four Nansen-class frigates. It cannot be excluded that the same applies to vessels of a similar design delivered by Navantia, or that the design concept continues to be used for similar vessel models.”

Update, 24 June 2019: The Norwegian government has decided to scrap the ship rather than undertake repairs.

To no one's surprise, #Norway has officially decided to scrap the #frigate #HELGEINGSTAD F313 rather than repair her. Repairs would cost a bit more than building a new ship. The govt wants to replace the lost capability but has yet to decide how. https://t.co/eslMmkQ6Jj pic.twitter.com/o0YB2R4zrY

— Chris Cavas (@CavasShips) June 23, 2019

November 19, 2018

What we know about the sinking of the HNoMS Helge Ingstad near Bergen

The Verdigris blog has a very interesting analysis of what seems to have happened leading up to the collision of the Norwegian frigate HNoMS Helge Ingstad and the tanker Sola TS in the restricted waters near Bergen:

HNoMS Helge Ingstad, a Fridtjof Nansen-class frigate commissioned in 2009.

Photo detail via Wikimedia Commons

The island west of the collision location is Alvoyna in the Oygarden municipality, and the oil terminal at Sture is a busy port that receives large tankers such as the Sola TS which was involved in the collision. Otherwise the islands in this area are relatively sparsely populated with just 4,900 or so inhabitants across the whole municipality. From that we can assume that there would be few lights at night to mark the shoreline, with the exception of the oil terminal which would be brightly lit. The channel is approximately 2 miles wide but is relatively deep, narrowing south of Sture into a channel little over a mile wide.

The collision occurred at approximately 0400 local time on Thursday 8th November 2018. Sunset the previous evening was at approximately 1623; sunrise would not be until 0821. There was no moon; the moon set at around 1718 the previous day and would not rise until 0847. We cannot be certain of the weather conditions which may have restricted visibility. However, there is no evidence of weather or high seas on the radar picture and if visibility was restricted by rain or fog, a ship would be unlikely to be sailing at high speed.

Finally the ships involved. Sola TS is a Maltese flagged oil tanker of 62,000 tonnes. We know she had 23 personnel onboard and after the collision was reported to have little or no damage. Merchant ships are usually well built, especially when carrying petroleum cargoes which if leaked could have devastating environmental consequences; consequently the lack of damage is hardly a surprise. As a result they are sluggish, slow to manoeuvre or accelerate/decelerate. They are not, however, considered to be ‘restricted in their ability to manoeuvre’, a special condition identified in the International Regulations for the Prevention of Collision at Sea – the IRPCS or ‘Rules of the Road’ – this is a condition applied only to vessels which are restricted by their work, such as picking up or laying submarine cables or pipelines, launching or recovering aircraft, carrying out underway replenishment, etc. Sola TS might have been slow to manoeuvre, but she is not exceptional and is unlikely to have carried any special status. Sola TS had a tug, Tenax, in company and might conceivably have been considered to be under tow; however, once again no special status is conferred unless the nature of the tow made it particularly difficult to alter course. The tug is more than likely to have been pacing the tanker, probably not connected and likely a precaution for a fully laden oil tanker in narrow waters.

Helge Ingstad, by contrast, is a Fridtjof Nansen-class air defence frigate of just 5,290 tonnes. Lightly built for speed and manoeuvrability, warships are invariably less robust than merchant ships, but are more tightly compartmented and have more complex damage control arrangements to compensate.

Very quickly after the collision, the Helge Ingstad was run ashore to prevent the ship sinking, but the ship slid down further into the water, despite attempts to keep her close in shore, and eventually slipped down almost completely beneath the waterline:

The consensus among the commenters is that the ship can probably be re-floated, but that the damage to the electronic gear onboard most likely renders her a complete loss:

Regardless of the circumstances, the loss of Helge Ingstad, even temporarily, is a major blow to the Royal Norwegian Navy, which relies on the Fridtjof Nansen-class as its primary surface combatants, especially in a time of increased tensions between Norway and its NATO allies and Russia. The frigate had been on its way back from a massive NATO-led exercise, called Trident Juncture, the largest such drill in decades, when the accident occurred.

If it turns out that Helge Ingstad is a total loss, which seems likely at this point, it could have a significant impact on Norwegian naval operations for years to come. In the meantime, we will continue to follow this story closely and provide any additional updates as they become available.

October 5, 2018

Know Your Ship #50 – C and D Class Destroyers – HMS Crescent & Diana, HMCS Fraser & Margaree

iChaseGaming

Published on 10 Sep 2018A Know Your Ship episode talking about C & D class destroyers, in particular HMS Crescent and Diana and their later service as part of the Royal Canadian Navy HMCS Fraser and Margaree. Enjoy!

March 7, 2018

USS Lexington‘s final resting place discovered by Paul Allen’s RV Petrel

As reported by News Corp Australia:

U.S. Navy Martin T4M-1 aircraft of Torpedo Squadron 1B (VT-1B) are launching from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-2) in 1931. Note the “four-stacker” (Clemson/Wickes-class destroyer) in the upper right corner.

US Navy photo via Wikimedia.

Now, 76 years after it settled to the bottom, it’s been found.

It’s the latest find by billionaire Paul Allen.

And it’s in a remarkably well preserved condition.

Soon-to-be US ambassador to Australia, US Pacific Commander Admiral Harry Harris says he is elated at the find.

“As the son of a survivor of the USS Lexington, I offer my congratulations to Paul Allen and the expedition crew of Research Vessel Petrel for locating the ‘Lady Lex’,” he said in a tweet.

[…]

Paul Allen’s research vessel Petrel located the wreck of the USS Lexington yesterday.

According to a post on the philanthropist’s website, it rests some 800km off the coast of Queensland at a depth of about 3km.

The find was the result of a six month project.

Photos so far returned by RV Petrel’s submersible show several aircraft that have tumbled out of the carrier and on to the ocean’s floor. Their original markings and paintwork remain remarkably clear.

The ship itself, while showing heavy scarring from the battle and the stresses of diving 3km to the sea floor, is also well preserved. Gun mounts and other fittings show only little sign of corrosion and deterioration.

Vulcan Inc.

Published on 5 Mar 2018Wreckage from the USS Lexington was discovered on March 4, 2018 by the expedition crew of Paul G. Allen’s Research Vessel (R/V) Petrel. The aircraft carrier, “Lady Lex” was found more than 3,000 meters below the surface, resting on the floor of the Coral Sea more than 500 miles off the eastern coast of Australia.

January 30, 2018

Fitness tracker heat map shows dangerous activity near wrecked WW2 ammunition ship

The SS Richard Montgomery was a WW2 Liberty ship that ran aground near Sheerness in August 1944 carrying a cargo of bombs and other explosives. Part of the cargo was removed before the ship broke up and sank just offshore. There’s still quite a lot of TNT onboard the wreck, and it’s recently come to light that someone has been visiting the wreck, thanks to fitness tracker data:

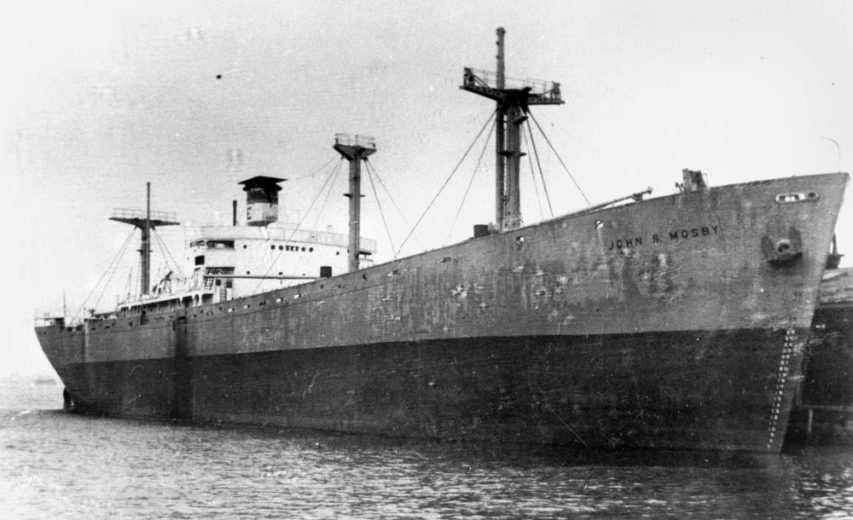

The SS John S. Mosby, a Liberty ship similar to the SS Richard Montgomery

Photo from the John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, via Wikimedia.

The information came to light after social media users realised that the latest version of Strava’s heat map, which shows the aggregated routes of all of its users, could be used to figure out where Western military bases in the Middle East are. Fitness-conscious soldiers, running around the bases’ perimeters, built up visible traces on the heat map over time.

However, of much more concern is the revelation that people have been poking around the wreck of the SS Richard Montgomery, a Second World War cargo ship that was carrying thousands of tonnes of explosive munitions from America to the UK. The ship grounded in the Thames Estuary, in England, in August 1944, barely two miles north of Sheerness.

Extract from Admiralty chart of Sheerness (Crown copyright):

The multicoloured box is the location of the SS Richard Montgomery wreckAlthough wartime salvage parties managed to scavenge a large amount of ordnance from the grounded Liberty ship, her hull split in two and sank, taking around 1,400 tonnes of explosives down with her, before the job could be completed. Officials decided to leave the wreck in place.

According to a 1995 survey report [PDF] on the wreck: “The bombs thought to be on board are of two types. The bulk are standard, un-fused TNT bombs. In addition, some 800 fused cluster bombs are believed to remain. These bombs were loaded with TNT. They could be transported fused because the design included a propeller mechanism at the front which only screwed the fuse into position as the bombs fell from an aircraft. All the bombs could therefore be handled – with care – when the accident occurred.”

[…]

The 1995 report noted that TNT “does not react with water and will not explode if it is damp”, before adding that the brass-cased cluster bombs’ lead-based fuses “will combine with brass to produce a highly unstable copper compound which could explode with the slightest disturbance”. Although the compound “if formed, will wash away in a few weeks”, it was not made clear in the report how often the compound forms and creates the dangerous hair-trigger condition. Experts believe that the best way of keeping the wreck safe is not to disturb it, which led to a 500-metre exclusion zone being imposed around it.

I thought the ship’s name sounded familiar … I posted a video about the dangers of this wreck back in 2013. Last month, I posted a video about the Liberty ship program.

December 8, 2017

Halifax Explosion – Peace in the East? | THE GREAT WAR Week 176

The Great War

Published on 7 Dec 2017This week in the Great War, we see some action in Italy and none at all in Russia – the peace negotiations are well underway. The Allied Supreme War Council meets for the first time as the Battle of Cambrai comes to a close. Two ships collide in Nova Scotia resulting in a deadly explosion.

December 7, 2017

The battleships of Pearl Harbour

Last month Naval Gazing ran a three-part series on the US Navy battleships at Pearl Harbour on the morning of 7 December, 1941, their post-attack fates, and later careers in World War 2. Part 1 was about the initial Japanese attack:

In Pearl Harbor on December 7th were eight battleships: Nevada, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Tennessee, California, West Virginia and Maryland. All of them were of First World War vintage, representatives of what was known as the Standard Type. These were ships commissioned between 1914 and 1923, all of broadly the same size, and the first ships designed for long-range combat using an all-or-nothing armor scheme. All had four turrets, and all but West Virginia and Maryland mounting 14” guns. (They had 16” guns instead.)

Pearl Harbour at the beginning of the attack, Battleship Row at the top (the waterspout is the first torpedo hit on the USS West Virginia)

All of the ships except Pennsylvania (which was in drydock) were moored along Ford Island in the famous ‘battleship row’. I’m going to focus on the stories of the individual ships during the attack, moving north to south. The attack began at 0748 on Sunday, December 7th, and a total of 353 Japanese aircraft were involved, in two waves.

The second post in the series covered the salvage of the damaged US Navy battleships:

When we left Pearl Harbor, it was the evening of December 7th, and most of Battle Force was on the bottom of the harbor. But what happened to the ships afterwards? We’ll go through the ships in the order which they returned to service (if they did) and then look more broadly at the use of the survivors during the war.

Battleship Row, 8 December 1941. Left-to-right: Maryland, Oklahoma, Tennesee, West Virginia, Arizona.

Maryland was the first ship ready to go to sea again, albeit with some damage. Tennessee was slightly behind her, as she was wedged by the West Virginia. Both ships were sent to Puget Sound at the end of the year, and repairs were completed in February. Pennsylvania was sent to San Francisco at the same time, returning to duty in March. All three ships (along with Colorado, New Mexico, Mississippi, and Idaho) served as part of TF 1, the backup to the carrier fleet until after Midway. Tennessee and Pennsylvania were sent to the states for comprehensive refit, running 8/42-5/43 and 10/42-2/43 respectively. Both received the standard upgrade, a reconstructed superstructure resembling those on the fast battleships (although there was less work done on Pennsylvania than the others), 5”/38 secondary guns in place of the former mixed secondary battery and upgraded fire control. Tennessee was also blistered against torpedoes, restricting her to the Pacific or a long journey around South America. Maryland was never refitted.

Part 3 discussed the Pearl Harbour survivors at the battle of Leyte Gulf:

The invasion began on Leyte Island in October of 1944, and triggered the largest naval battle in history, the battle of Leyte Gulf. The Japanese, who had long planned for the ‘Decisive Battle’ between their battleships and those of the US, planned a counterattack on the US landings in three main groups. Their carriers would come in from the north and draw off the US carriers covering the invasion, while two groups of battleships would sneak up on the invasion fleet from the east, passing through the Philippines and pincering the US transports from the north and south.

The northern group (basically without planes after severe losses in June during the Battle of the Philippine Sea) managed to draw off Admiral Halsey. He’s often criticized for this, but in fairness, he was tasked with destroying the Japanese fleet, and the US didn’t realize how badly the carrier air groups had been hammered. The center group (with the faster battleships) had been detected, and appeared to have turned back after Musashi, Yamato’s sister ship, was sunk. They in fact resumed their course, and their encounter with escort carrier group Taffy 3 is the stuff of legend, but also a matter for another time.

December 5, 2017

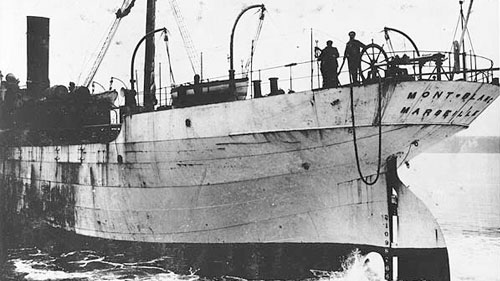

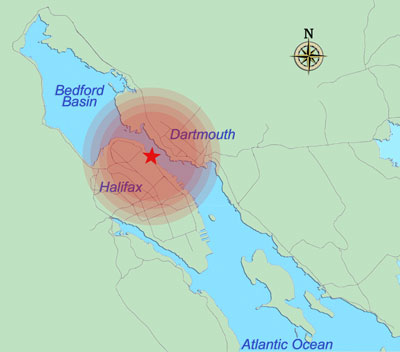

The Halifax explosion of 6 December, 1917

It’s been called one of the largest man-made non-nuclear explosions and it destroyed large parts of the City of Halifax, when the SS Mont Blanc ran aground and exploded following a collision in the Narrows between Halifax and Dartmouth with the chartered Belgian Relief ship SS Imo. Nearly two thousand people were killed and thousands more injured in the blast.

A view of the Halifax waterfront shortly after the explosion on the morning of 6 December, 1917

Image via Wikimedia.

The Mont Blanc was built in 1899 in Middlesbrough, England, and at the time of the explosion was owned by Cie Generale Transatlantique with a St. Nazaire registration. As far as I’m aware there is only one photo of the ship and it shows the stern of the vessel when she was sailing under a Marseilles registration:

Mont Blanc had left New York harbour with a full load of flammable and explosive cargo (including TNT, picric acid, benzol aviation fuel additive, and guncotton) intended for the battlefront in western Europe on the first, and just missed being allowed inside the anti-submarine netting protecting the entrance to the harbour on the evening of the fifth, being forced to wait outside until morning. As soon as the harbour guard allowed passage, the Mont Blanc followed another freighter (believed to be the SS Clara, but identified only as “the green American tramp steamer” in the inquiry) through the barrier and approached the narrows.

As the Mont Blanc made her way up toward the Bedford Basin, the Imo started in the opposite direction headed toward the harbour mouth. The Clara was sailing up the Halifax side of the channel, contrary to harbour rules, so the Imo had to swing over toward the Dartmouth side to avoid the Clara, and then further to the wrong side of the Narrows to avoid the Stella Maris, a tug moving barges around the harbour. In the low visibility, Imo‘s captain and pilot were unaware that another ship was following the Clara so closely and on the correct side of the channel.

According to the accepted “rules of the road”, in this situation the first ship to signal has the right of way and the other ship is expected to defer to the movement of the first ship. Mont Blanc‘s pilot had the ship’s whistle blown once, to indicate their priority, but the Imo replied with two whistles indicating that they did not intend to allow Mont Blanc‘s right of way. At first sighting, the two ships were already within a mile of one another and within the narrowest point of the harbour, which restricted the ability of the Mont Blanc to manouvre. The captain ordered the engines stopped and to steer closer to the Dartmouth side of the channel (with his delicate and explosive cargo, he didn’t want to run the risk of going aground).

Imo was carrying no cargo on this portion of her journey, which meant the propellers were partially out of the water, making the ship much less handy to steer. As the two ships approached, with the ships on approximately parallel courses, the Imo‘s captain ordered the engines to reverse, which caused Imo to swing to starboard (right) and impact the starboard side of the Mont Blanc at 8:45am. The collision did not do fatal structural damage to either ship, but it broke open some of the benzol containers on the deck and the spilled liquid ran down the side of the Mont Blanc, producing a flammable vapour.

The immediate impact of the explosion covered 325 acres, and windows were broken more than 50 miles away.

Image from http://www.halifaxexplosion.org/explosion2.html

As the Imo‘s engines began to pull the ship back, friction between the two hulls ignited the benzol fumes, which then spread the fire up the hull and onto the foredeck, preventing any effective fire-fighting on the part of the Mont Blanc‘s crew. With no hope of preventing an explosion, the crew abandoned ship and rowed away from the stricken Mont Blanc, which carried on across the channel and eventually ran aground on the Halifax side near Pier 6 at the foot of Richmond Street. At 9:04am, the main cargo exploded, ripping the ship apart and sending chunks of the hull out over the buildings at the waterfront, some landing up to 3.5 miles away from the site of the blast.

This photo was taken two days after the explosion, looking across the Narrows toward the wreck of the SS Imo, aground on the Dartmouth shore.

Image via Wikimedia.

The Wikipedia entry tells of the moment of the explosion:

The ship was completely blown apart and a powerful blast wave radiated away from the explosion at more than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) per second. Temperatures of 5,000 °C (9,030 °F) and pressures of thousands of atmospheres accompanied the moment of detonation at the centre of the explosion. White-hot shards of iron fell down upon Halifax and Dartmouth. Mont Blanc‘s forward 90 mm gun, its barrel melted away, landed approximately 5.6 kilometres (3.5 mi) north of the explosion site near Albro Lake in Dartmouth, while the shank of her anchor, weighing half a ton, landed 3.2 kilometres (2.0 mi) south at Armdale.

A cloud of white smoke rose to over 3,600 metres (11,800 ft). The shock wave from the blast travelled through the earth at nearly 23 times the speed of sound and was felt as far away as Cape Breton (207 kilometres or 129 miles) and Prince Edward Island (180 kilometres or 110 miles). An area of over 160 hectares (400 acres) was completely destroyed by the explosion, while the harbour floor was momentarily exposed by the volume of water that vaporized. A tsunami was formed by water surging in to fill the void; it rose as high as 18 metres (60 ft) above the high-water mark on the Halifax side of the harbour. Imo was carried onto the shore at Dartmouth by the tsunami. The blast killed all but one on the whaler, everyone on the pinnace and 21 of the 26 men on Stella Maris; she ended up on the Dartmouth shore, severely damaged. The captain’s son, First Mate Walter Brannen, who had been thrown into the hold by the blast, survived, as did four others. All but one of the Mont Blanc crew members survived.

Over 1,600 people were killed instantly and 9,000 were injured, more than 300 of whom later died. Every building within a 2.6-kilometre (1.6 mi) radius, over 12,000 in total, was destroyed or badly damaged. Hundreds of people who had been watching the fire from their homes were blinded when the blast wave shattered the windows in front of them. Stoves and lamps overturned by the force of the blast sparked fires throughout Halifax, particularly in the North End, where entire city blocks were caught up in the inferno, trapping residents inside their houses. Firefighter Billy Wells, who was thrown away from the explosion and had his clothes torn from his body, described the devastation survivors faced: “The sight was awful, with people hanging out of windows dead. Some with their heads missing, and some thrown onto the overhead telegraph wires.” He was the only member of the eight-man crew of the fire engine “Patricia” to survive.

Intercolonial Railway dispatcher Vince Coleman is credited with saving some three hundred passengers of an inbound Saint John train, by going back to the telegraph office and ordering the train to stop outside the likely blast zone: “Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbor making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys.” The train was only slightly damaged and there were no fatalities onboard. Coleman died at his post when the ship exploded.

The earliest rescue efforts were mounted by the crews of British, Canadian, and American naval ships in port, and two US Navy ships that arrived later in the day. Many wounded were brought aboard the ships and treated there: the explosion having taken down all the electric power lines in the area, these were the best-lighted-and-heated places to take the injured until emergency power lines could be set up onshore.

Later in the day, a small fire near the magazine of Wellington Barracks caused a panic about a second explosion which hampered early rescue attempts adjacent to the blast area. Rescue trains were dispatched from many communities in the Maritimes and New England, including a major relief effort from Boston. A severe winter storm struck Halifax the next day, causing further delays in locating and assisting wounded and injured Haligonians. Sixteen inches of snow blocked several railway lines, and caused greater distress among the survivors, and knocking out the telegraph lines that in many cases had only just been re-connected after the blast.

For further reading on the explosion, the rescue efforts, and the aftermath, I can recommend Laura M. Mac Donald’s Curse of the Narrows, which recounts a great many individual stories of the people of Halifax and Dartmouth who lived through the disaster.

Update, 6 December: Rick Tessner sent me a link to this video which does a good job of explaining what happened to cause the explosion.

Sixty Symbols

Published on Dec 4, 2017Sixty Symbols regular Dr Meghan Gray on an infamous event that occurred in her home town – the Halifax Explosion of December 6, 1917.

MORE DETAILS

Maritime Museum of the Atlantic: https://maritimemuseum.novascotia.ca/…

Nova Scotia archives stuff: https://novascotia.ca/news/smr/2009-1…

CBC: http://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/halifa…While not a typical video for us, Dr Gray is a Sixty Symbols stalwart and really wanted to share the story of this explosion which is an event of great interest to her home town of Halifax — and an event with a pretty significant science component.

August 25, 2017

Solving the mystery of the fate of H.L. Hunley‘s crew

When the Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley was found, the bodies of the crew were still in their duty positions within the vessel, as if they’d been unaware or unable to do anything to save the situation. Sarah Knapton reports on what is now believed to have killed the crew almost instantaneously:

“Submarine Torpedo Boat H.L. Hunley, Dec. 6, 1863″ by Conrad Wise Chapman.

“The inventor of this boat, a man named Hunley, can be seen; also a sentinel. This boat, it was at first thought would be very effective; twice it went out on its mission of destruction, but on both occasions returned with all the crew dead. After this had happened the second time, someone painted on it the word ‘coffin.’ There was just room enough in it for eight men, one in front of the other, with no possibility of anyone sitting straight. The third time it started out, it never came back, nor was anything ever heard from it, but as one of the United States men-of-war in the harbor (USS Housatonic) was sunk at about the same time, the supposition was that they both went to the bottom together. Other objects to be seen in the picture are, Sullivan’s Island, and a Dispatch boat.” – Conrad Wise Chapman, 1898 (via Wikimedia)

The mystery of how the crew of one of the world’s first submarines died has finally been solved – they accidentally killed themselves.

The H.L. Hunley sank on February 17 1864 after torpedoing the USS Housatonic outside Charleston Harbour, South Carolina, during American Civil War.

She was one of the first submarines ever to be used in conflict, and the first to sink a battleship [Housatonic was actually a sloop-of-war, not a battleship].

It was assumed the blast had ruptured the sub, drowning its occupants, but when the Hunley was raised in 2000, salvage experts were amazed to find the eight-man crew poised as if they had been caught completely unawares by the tragedy. All were still sitting in their posts and there was no evidence that they had attempted to flee the foundering vessel.

Now researchers at Duke University believe they have the answer. Three years of experiments on a mini-test sub have shown that the torpedo blast would have created a shockwave great enough to instantly rupture the blood vessels in the lungs and brains of the submariners.

“This is the characteristic trauma of blast victims, they call it ‘blast lung,'” Dr Rachel Lance.

“You have an instant fatality that leaves no marks on the skeletal remains. Unfortunately, the soft tissues that would show us what happened have decomposed in the past hundred years.”

The Hunley‘s torpedo was not a self-propelled bomb, but a copper keg of 135 pounds of gunpowder held ahead and slightly below the Hunley‘s bow on a 16-foot pole called a spar

The sub rammed this spar into the enemy ship’s hull and the bomb exploded. The furthest any of the crew was from the blast was about 42 feet. The shockwave of the blast travelled about 1500 meters per second in water, and 340 m/sec in air, the researchers calculate.

January 8, 2017

Secrets of the Dead: What Sank The Mary Rose?

Published on Aug 13, 2015

Henry VİII’s and England’s most important battleship, the Mary Rose, sunk off the English coast in the Solent in the 16th Century.Secrets Of The Dead – What Sank The Mary Rose?

July 2, 2015

Frankford Junction, Pennsylvania

Rob McGonigal looks at the history of the railways in the area of Frankford Junction, where Amtrak train 188 came to grief in May:

In the aftermath of the tragic May 12 derailment due to excessive speed of Amtrak train 188 in Philadelphia, many casual observers wondered what a 50-mph curve is doing in the middle of the fastest, busiest rail corridor in the nation. It’s a reasonable question, especially given the generally tangent track and flat topography in the area.

The existence of that curve traces back to the earliest years of railroads in Philadelphia. As in many cities, Philadelphia’s rail network developed in piecemeal, uncoordinated fashion. What became Amtrak 188’s route through the city began in the 1830s as three separate projects.

The Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore ran generally southwestward from a terminal about a mile south of downtown (“center city” to Philadelphians). The Philadelphia & Columbia, part of the Main Line of Public Works rail/canal system to Pittsburgh, utilized a terminal in center city. The Philadelphia & Trenton, which connected with services to New York, originated in Kensington — an inconvenient 2½ miles northeast of center city. As Albert Churella relates in the first volume of his mammoth history of the PRR (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), municipal authorities in 1840 granted the P&T permission to extend its line into center city, where it would connect with other railroads. However, fierce opposition from teamsters, who profited from hauling freight between the rail terminals, and area residents, who did not want steam trains in their streets, prompted the city to revoke permission, and the P&T was not extended.

Two decades later, it was clear that the three lines should be connected. In 1864 the Junction Railroad was opened, linking the PW&B with the P&C’s successor on the line to the west — the Pennsylvania Railroad. (Indeed, the PRR had interests in all three of the lines by this time.) Three years later the Connecting Railway opened. It diverged from the P&C/PRR line at a place designated Mantua Junction (and later, in expanded form, Zoo interlocking), arced around the northern part of the city, and connected with the P&T in the Frankford section of Philadelphia. As with the connection at Mantua Junction, the geometry of the lines at Frankford Junction resulted in a sharp curve.

May 11, 2015

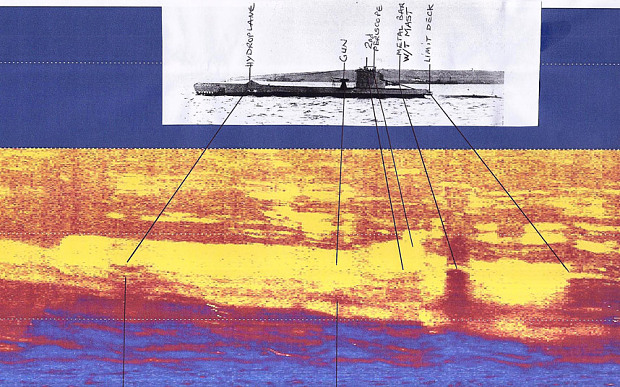

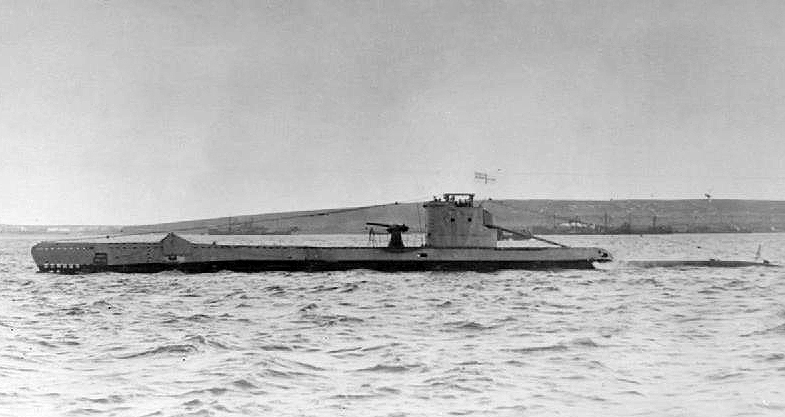

After 74 years, the remains of HMS Urge discovered off the Libyan coast

In The Telegraph a report on the discovery of a Royal Navy submarine wreck from 1942:

A Royal Navy submarine paid for by a town holding dances and whist drives is believed to have been discovered more than 70 years after it vanished during the Second World War.

The British submarine HMS Urge was paid for by the townspeople of Bridgend, South Wales, but sunk without trace in the Mediterranean in 1942.

It disappeared while making a voyage from the island of Malta to the Egyptian city of Alexandria – and families of the 29 crew and 10 passengers never knew what happened.

For more than 70 years, its resting place has remained a mystery. But a 76-year-old scuba diver claims he has discovered its wreck 160ft (50m) below the waves off the Libyan coast.