David Warren explains how he deduced that William Shakespeare was probably a Catholic:

Long before I became a Catholic, I realized that Shakespeare was one: as Catholic as so many of the nobles, artists, musicians and composers at the Court of Bad Queen Bess. I did not come to this conclusion because some secret Recusant document had fallen into my hands; or because I subscribed to any silly acrostic an over-ingenious scholar had descried, woven into a patch of otherwise harmless verses. My view came rather from reading the plays. The Histories especially, to start: which also helped form my reactionary politics, contributing powerfully to my contempt for mobs, and the demons who lead them. But with improvements of age, I now see an unmistakably Catholic “worldview” written into every scene that is indisputably from Shakespeare’s hand. (This recent piece by another lifelong Shakespeare addict — here — will spare me a paragraph or twenty.)

That our Bard came from Warwickshire, to where he returned after tiring of his big-city career, tells us plenty to start. The county, as much of Lancashire, Yorkshire, the West Country, and some other parts of England, remained all but impenetrable to Protestant agents and hitmen, well into Shakespeare’s time. Warwick’s better houses were tunnelled through with priest holes; and through Eamon Duffy and other “revisionist” historians we are beginning to recover knowledge of much that was papered over by the old Protestant and Statist propaganda. The story of Shakespeare’s own “lost years” (especially 1585–92) has been plausibly reconstructed; documentary evidence has been coming to light that was not expected before. Yet even in the eighteenth century, the editor Edmond Malone had his hands on nearly irrefutable evidence of the underground commitments of Shakespeare’s father, John; and we always knew the Hathaways were papists. Efforts to challenge such forthright evidence, or to deny its significance, are as old as the same hills.

But again, “documents” mean little to me, unless they can decisively clinch a point, as they now seem to be doing. Even so, people will continue to believe what they want to believe. In Wiki and like sources one will often find the most telling research dismissed, without examination, with a remark such as, “Against the trend of current scholarship.”

That “trend” consists of “scholars” who are not acquainted with the Bible (to which Shakespeare alludes on every page); have no knowledge of the religious controversies of the age, or what was at stake in them; show only a superficial comprehension of the Shakespearian “texts” they pretend to expound; assume the playwright is an agnostic because they are; and suffer from other debilities incumbent upon being all-round drooling malicious idiots.

Perhaps I could have put that more charitably. But I think it describes “the trend of current scholarship” well enough.

Now here is where the case becomes complicated. As something of a courtier himself, in later years under royal patronage, Shakespeare would have fit right into a Court environment in which candles and crucifixes were diligently maintained, the clergy were cap’d, coped, and surpliced, the cult of the saints was still alive, and outwardly even though Elizabeth was Queen, little had changed from the reign of Queen Mary.

The politics were immensely complicated; we might get into them some day. The point to take here is that the persecution of Catholics was happening not inside, but outside that Court. Inside, practising Catholics were relatively safe, so long as they did not make spectacles of themselves; and those not wishing to be hanged drawn and quartered, generally did not. It was outside that Queen Elizabeth walked her political tightrope, above murderously contending populist factions. She found herself appeasing a Calvinist constituency for which she had no sympathy, yet which had become the main threat to her rule, displacing previous Catholic conspirators both real and imagined. Quite apart from the bloodshed, those were interesting times, in every part of which we must look for motives to immediate context, before anywhere else. Eliza could be a ruthless, even fiendish power politician; but she was also an extremely well-educated woman, and in her tastes, a pupil of the old school.

Indeed the Puritans frequently suspected their Queen, despite her own Protestant protestations, of being a closet Catholic; and suspected her successor King James even more. A large part of the Catholic persecution in England was occasioned by the need to appease this “Arab spring” mob, concentrated in the capital city. Their bloodlust required human victims. The Queen and then her successor did their best to maintain, through English Bible and the Book of Common Prayer, the mediaeval Catholic inheritance, while throwing such sop to the wolves as the farcical “Articles of Religion.”

The question is not whether Shakespeare was one of the many secretly “card-carrying” Catholics. I think he probably was, on the face of the evidence, but that is a secondary matter. It is rather what Shakespeare wrote that is important. His private life is largely unrecoverable, but what he believed, and demonstrated, through the media of his plays and poems, remains freely available. He articulates an unambiguously Catholic view of human life in the Creation, and it is this that is worth exploring. The poetry (in both plays and poems) can be enjoyed, to some degree, and the dramatic element in itself, even if gentle reader has not twigged to this, just as Mozart can be enjoyed by those who know nothing about music. But to begin to understand as astute an author as was ever born, and to gain the benefit from what he can teach — his full benevolent genius — one must make room for his mind.

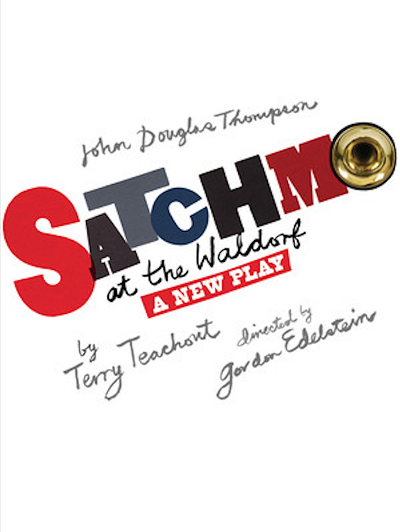

As Terry Teachout was finishing Pops: A Life, his 2009 biography of Louis Armstrong, he had an idea. Realizing that Armstrong’s final performance at the Waldorf in 1971 was an operatic moment — a meet-your-maker crescendo in the life of a great artist — Terry wrote a theatrical work where the trumpeter reflects on his life, and his white manager, Joe Glaser, adds his thoughts. The radical device was having the same black actor play both parts.

As Terry Teachout was finishing Pops: A Life, his 2009 biography of Louis Armstrong, he had an idea. Realizing that Armstrong’s final performance at the Waldorf in 1971 was an operatic moment — a meet-your-maker crescendo in the life of a great artist — Terry wrote a theatrical work where the trumpeter reflects on his life, and his white manager, Joe Glaser, adds his thoughts. The radical device was having the same black actor play both parts.