Published on 29 Aug 2016

Submarine warfare is one of the lasting impacts of World War 1. Especially the unrestricted submarine warfare by the German navy was a big problem for the British supply routes. But the development and improvement of submarines was not a German story at first.

August 30, 2016

The Invention And Development of Submarines I THE GREAT WAR Special

June 16, 2016

Silent Victory now available in wargame format

I’m currently reading this two-volume history of the US Navy’s submarines in the Pacific during WW2 by Clay Blair, Jr., so I was interested to see this review of a wargame covering this exact conflict:

Consim Press has published a fantastic solo player wargame in Silent Victory: U.S. Submarines in the Pacific, 1941-1945. With game design by Gregory M. Smith, Silent Victory offers a little bit of everything for someone looking for an immersive, historical naval wargame that is easy to play yet detailed enough to be fulfilling for an advanced gamer.

It covers one of the biggest problems American sub commanders faced for the first two years of the war:

For every torpedo you fire, you’ll roll a 1d6 dice for a dud. Roll a 1 or 2, well, you are out of luck. It might have hit, but it didn’t explode. Dud. This happened to me at least three times in two patrols. It was a fact — the U.S. Navy had a torpedo problem. Clay Blair Jr.’s magisterial book Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War against Japan made this clear:

“…[T}he submarine force was hobbled by defective torpedoes. Developed in peacetime but never realistically tested against targets, the U.S. submarine torpedo was believed to be one of the most lethal weapons in the history of naval warfare. It had two exploders, a regular one that detonated it on contact with the side of an enemy ship and a very secret “magnetic exploder” that would detonate it beneath the keel of a ship without contact. After the war began, submariners discovered the hard way that the torpedo did not run steadily at the depth set into its controls and often went much deeper than designed, too deep for the magnetic exploder to work.”

Blair notes that not until late 1943 would the U.S. Navy fix the numerous torpedo problems.

Actually, the depth control issue was only the start of the problem. Once enough sub skippers had complained to their chain of command that the torpedoes were running too deep, and were able to get a few of them tested to prove it, then other problems became apparent. Even if the torpedo ran at the correct depth, the magnetic exploder would not reliably trigger the warhead when it passed under an enemy ship. The German and British submarine services had also developed similar exploders, but had abandoned them after wartime testing proved them to be ineffective. US Navy submarine admirals would not be convinced, so it took much longer for the sub captains to get permission to de-activate the magnetic exploders and use the contact exploders instead.

Unbelievably, it now became clear that there were also problems with the contact exploder as well, so even if it hit the side of the target it might not explode. American torpedoes had a significantly smaller warhead than those of other navies, because it had been expected that the magnetic exploder detonating below the keel of an enemy ship would be sufficient to break the back of the target and sink it. When used as ordinary torpedoes, it often took three or four hits to guarantee a sinking even on a merchant ship. Warships, having better compartmentalization, were even tougher to sink without lucky shots that hit fuel or ammunition compartments.

There are three reasons why this game succeeds.

First, historical accuracy. From the problems with torpedoes, to the detailed lists of Japanese merchant and capital ships, or to the specific weapons load out of each U.S. submarine in WWII, it is all there. The makers of this game did not cut any corners. They did their homework and tried, I think successfully, to incorporate significant historical facts into the gameplay.

Second, a risk/reward based gameplay experience. Every decision you make — from the torpedoes you use to deciding if you want to attack submerged and at close or long distance — incurs risk. There are numerous tradeoffs. For instance, you can attack from long distance submerged, but you suffer a roll modifier and risk not hitting your target. Or, you can be aggressive, and attack at close range, surfaced at night, which may increase your chance of hit but also increase your chance of detection. It just depends.

Finally, simple game rules. Complicated games are no fun to play. As a player, I don’t want to spend 10 minutes looking up rule after rule in a rulebook the size of a encyclopedia. In Silent Victory, the designers have done us a favor. The rules are clearly written and extensive, and after a single read through I referred to them occasionally. But more important, the combat mat has the dice roll encounter procedures printed on it, all within easy view. Also, the other mats all have reference numbers and clearly identify which dice should be rolled for what effects. It is all right there on the mats. This makes for a fun, smooth playing experience. And finally, if I were add another reason why this game is worth your money, it is the game’s replay value. You can conduct numerous patrols and no two patrols will ever be the same.

Silent Victory is a fun naval wargame that will appeal to the novice or expert gamer – and maybe you’ll learn something along the way.

May 6, 2016

The British Surrender At Kut – Germany Restricts The U-Boats I THE GREAT WAR – Week 93

Published on 5 May 2016

After 140 days, the Siege of Kut ends with the biggest surrender of British forces in history. The remaining soldiers are starting their long march into captivity. Meanwhile the Italian front lights up again as Luigi Cadorna plans a new offensive and the Germans give in to diplomatic pressure and stop their unrestricted submarine warfare.

March 27, 2016

The Russian Navy – Submarines – Trench Mortar I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

Published on 26 Mar 2016

More pictures from Flo’s Great Grandfather: https://imgur.com/a/R1T92

It’s chair of wisdom time again and this week we talk about the Russian Navy in the Baltic Sea, submarine warfare and trench mortars.

March 18, 2016

Battle of the Isonzo – Discord Among The Central Powers I THE GREAT WAR Week 86

Published on 17 Mar 2016

The alliance between the Central Powers of World War 1 doesn’t seem to be as strong anymore. The Bulgarians, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Germany are following their own goals without really helping out the other. Erich von Falkenhayn is obsessed with Verdun, Conrad von Hötzendorf wants to go on the offensive again after the 5th Battle of the Isonzo and the Bulgarians don’t have the resources to pursue their own goals. At the same time the unrestricted submarine warfare of the Germans is taking a deadly toll.

February 19, 2016

The Ghost Of The Lusitania – Russia Takes Erzurum I THE GREAT WAR – Week 82

Published on 18 Feb 2016

The sinking of the Lusitania is still causing diplomatic tensions between Germany and the USA. While the Germans insist they were forced by the British blockade to adopt unrestricted submarine warfare, the Americans think otherwise. In the meantime the Russian Army is taking Erzurum in the Caucasus and the big offensive at Verdun is delayed for a week.

December 16, 2015

How Did Submarine Warfare Change During World War 1? I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

Published on 12 Dec 2015

Indy sits in the Chair of Wisdom again to answer your questions of WW1. This time we are talking about submarine warfare during the First World War.

November 4, 2015

Sometimes the US Navy isn’t subtle

At the RCN News site, a recent press release from the US Navy expresses just a bit more than most civilian readers will get:

U.S. and Canadian naval units began a Task Group Exercise (TGEX) off the coast of Southern California, Oct. 20.

Participating units from the Royal Canadian Navy include Canadian Fleet Pacific, Halifax-class frigates HMCS Calgary (FFH 335) and HMCS Vancouver (FFH 331), and Victoria-class ASW target HMCS Chicoutimi (SSK 879).

Emphasis mine.

October 26, 2015

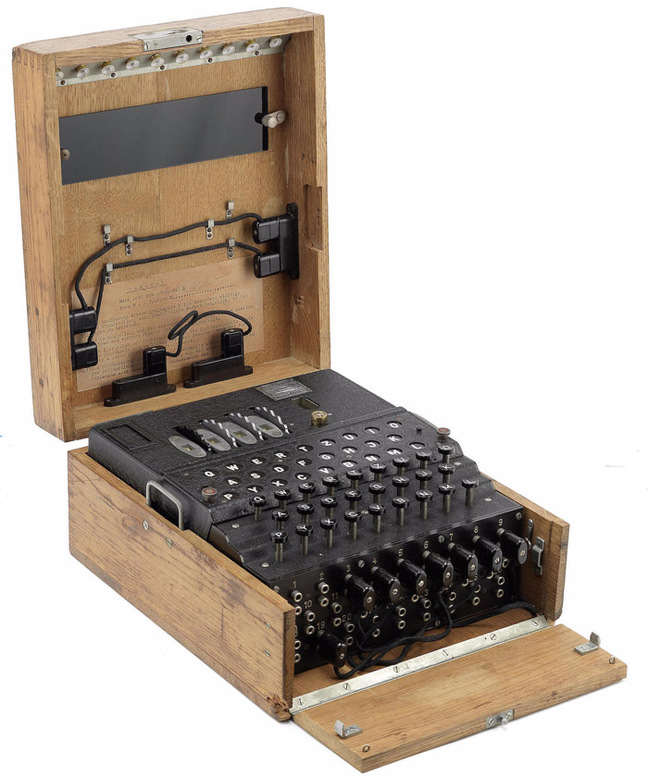

Going price for a working Enigma machine – $365,000

Lester Haines reports on a recent record auction price for an Enigma machine:

A fully-functioning four-rotor M4 Enigma WW2 cipher machine has sold at auction for $365,000.

The German encryption device, as used by the U-Boat fleet and described as “one of the rarest of all the Enigma machines”, went under the hammer at Bonham’s in New York last night as part of the “Conflicts of the 20th Century” sale.

The M4 was adopted by the German Navy, the Kriegsmarine, in early 1942 following the capture of U-570 in August 1941*. Although the crew of U-570 had destroyed their three-rotor Enigma, the British found aboard written material which compromised the security of the machine.

The traffic to and from the replacement machines was dubbed “Shark” by codebreakers at Bletchley Park. Decryption proved troublesome, due in part to an initial lack of “cribs” (identified or suspected plaintext in an encrypted message) for the new device, but by December 1942, the British were regularly cracking M4 messages.

I recently read David O’Keefe’s One Day in August, which seems to explain the otherwise inexplicable launch of “Operation Jubilee”, the Dieppe raid … in his reading, the raid was actually a cover-up operation while British intelligence operatives tried to snatch one or more of the new Enigma machines (like the one shown above) without tipping off the Germans that that was the actual goal. Joel Ralph reviewed the book when it was released:

One Day in August, by David O’Keefe, takes a completely different approach to the Dieppe landing. With significant new evidence in hand, O’Keefe seeks to reframe the entire raid within the context of the secret naval intelligence war being fought against Nazi Germany.

On February 1, 1942, German U-boats operating in the Atlantic Ocean switched from using a three-rotor Enigma code machine to a new four-rotor machine. Britain’s Naval Intelligence Division, which had broken the three-rotor code and was regularly reading German coded messages, was suddenly left entirely in the dark as to the positions and intentions of enemy submarines. By the summer of 1942, the Battle of the Atlantic had reached a state of crisis and was threatening to cut off Britain from the resources needed to carry on with the war.

O’Keefe spends nearly two hundred pages documenting the secret war against Germany and the growth of the Naval Intelligence Division. What ties this to Dieppe and sparked O’Keefe’s research was the development of a unique naval intelligence commando unit tasked with retrieving vital code-breaking material. As O’Keefe’s research reveals, the origins of this unit were at Dieppe, on an almost suicidal mission to gather intelligence they hoped would crack the four-rotor Enigma machine.

O’Keefe has uncovered new documents and first-hand accounts that provide evidence for the existence of such a mission. But he takes it one step further and argues that these secret commandos were not simply along for the ride at Dieppe. Instead, he claims, the entire Dieppe raid was cover for their important task.

It’s easy to dismiss O’Keefe’s argument as too incredible (Zuehlke does so quickly in his brief conclusion [in his book Operation Jubilee, August 19, 1942]). But O’Keefe would argue that just about everything associated with combined operations defied conventional military logic, from Operation Ruthless, a planned but never executed James Bond-style mission, to the successful raid on the French port of St. Nazaire only months before Dieppe.

Clearly this commando operation was an important part of the Dieppe raid. But, while the circumstantial evidence is robust, there is no single clear document that directly lays out the Dieppe raid as cover for a secret “pinch by design” operation to steal German code books and Enigma material.

August 21, 2015

Escalation At Sea and Russia Up Against the Wall I THE GREAT WAR – Week 56

Published on 20 Aug 2015

The Entente was in desperate need of American supplies and so the German submarine campaign in the Atlantic was a real problem. The British started to run false flag operations with so called Q-Ships to hunt down U-Boats which lead to the so called Baralong Incident this week. In the meantime, Russia was standing up against the wall as the fortresses of Kovno and Novogeorgievsk were falling to the Germans leading to a catastrophic loss in men, equipment and supplies.

May 20, 2015

Scuttled Soviet submarines in the Arctic

The Soviet Union had a remarkably casual approach to disposing of nuclear-powered submarines that were no longer useful in active service:

Russian scientists have made a worst-case scenario map for possible spreading of radionuclides from the wreck of the K-159 nuclear-powered submarine that sank twelve years ago in one of the best fishing areas of the Barents Sea.

Mikhail Kobrinsky with the Nuclear Safety Institute of the Russian Academy of Science says the sunken November-class submarine can’t stay at the seabed. The two reactors contain 800 kilos of spent uranium fuel.

At a recent seminar in Murmansk organized jointly by Russia’s nuclear agency Rosatom and the Norwegian environmental group Bellona, Kobrinsky presented the scenario map most fishermen in the Barents Sea would get nightmares by seeing.The map shows expected spreading of radioactive Cs-137 from potential releases from the K-159 that still lays on the seabed northeast of Murmansk in the Barents Sea.

Some areas could be sealed off for commercial fisheries for up to two years, Mikhail Kobrinsky explained.

Ocean currents would bring the radioactivity eastwards in the Barents Sea towards the inlet to the White Sea in the south and towards the Pechora Sea and Novaya Zemlya in the northeast.

May 11, 2015

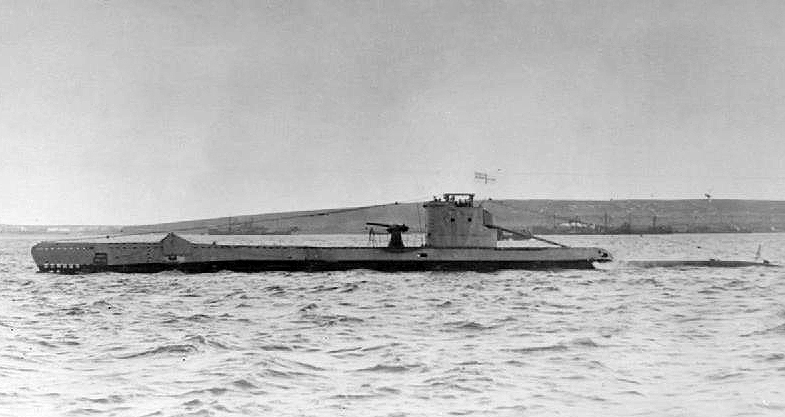

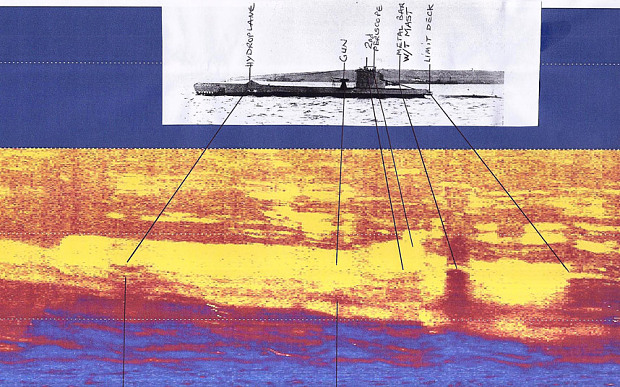

After 74 years, the remains of HMS Urge discovered off the Libyan coast

In The Telegraph a report on the discovery of a Royal Navy submarine wreck from 1942:

A Royal Navy submarine paid for by a town holding dances and whist drives is believed to have been discovered more than 70 years after it vanished during the Second World War.

The British submarine HMS Urge was paid for by the townspeople of Bridgend, South Wales, but sunk without trace in the Mediterranean in 1942.

It disappeared while making a voyage from the island of Malta to the Egyptian city of Alexandria – and families of the 29 crew and 10 passengers never knew what happened.

For more than 70 years, its resting place has remained a mystery. But a 76-year-old scuba diver claims he has discovered its wreck 160ft (50m) below the waves off the Libyan coast.

May 8, 2015

The Lusitania Sinking & The Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive I THE GREAT WAR – Week 41

Published on 7 May 2015

Ignoring the warnings and cruising carelessly slow the RMS Lusitania is hit by a torpedo of the German U-Boat U20. Almost 2000 people die during the sinking of the Lusitania, a sister ship of the famous RMS Titanic. At the same time the German and Austro-Hungarian army start a combined surprise offensive in the Carpathians. The Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive is a huge success for German commander August von Mackensen.

April 1, 2015

The RCN’s Victoria class submarines

Damian Brooks linked to this article in The Walrus, calling it “Easily the best piece on Canadian submarines I’ve ever seen in the mainstream press.”

The threat of fire is ever-present on warships, which is why fire training is conducted every day a Canadian vessel is in port and at least once a week when it’s at sea. But the fire on Chicoutimi, which already had experienced a four-year delay in getting out of port, could hardly have come at a worse time for Canada’s “silent service.” It fuelled a controversy that had begun in 1998 with the purchase of the ship and three other mothballed Upholder-class submarines from the United Kingdom’s Royal Navy. From the start, critics questioned the deal, which was supposed to cost $800 million for the subs and the conversion work required to bring them up to the Royal Canadian Navy’s requirements. (Few put it as succinctly as Mike Hancock, the British MP who asked, “Why were the Canadians daft enough to buy them?”) The fire simply added to what Paul Mitchell, a professor of defence studies at the Canadian Forces College in Toronto, calls an already “well-established narrative of waste and dysfunction.”

[…]

In 1943, thousands of Canadians bought a book, co-authored by humorist and early supporter of the RCN Stephen Leacock, that gave a reasonably clear account of the U-boat attacks on the St. Lawrence in 1942, which claimed twenty-one ships and 249 lives, including 136 aboard the ferry SS Caribou. Ultimately, Canada emerged from the war with the world’s fourth-largest navy, most of which was quickly scrapped, or “paid off.” In the late 1940s, the threat posed to transatlantic shipping by Soviet submarines led the navy to purchase the aircraft carrier HMS Magnificent, which was replaced in 1957 by HMCS Bonaventure. When the Trudeau government decided to decommission the carrier — Misadventure, as some wags had dubbed it — commentators intelligently discussed the anti-submarine capabilities of the ships that would replace it.

What passes for naval debate today is, by contrast, too often uninformed and sloppy. The Halifax Chronicle Herald reported in September 2011 that Chicoutimi was being “cannibalized” for parts for HMCS Victoria (not acknowledging that this practice, known as a transfer request, is standard RCN operating procedure). And most articles about the submarine program are riddled with errors and boilerplate references to the 2004 fire. Compare that to a 1969 fire, which killed nine men aboard the destroyer HMCS Kootenay and quickly vanished from a more sea-conscious news.

For much of the late twentieth century, Canada’s three British-built, diesel-electric Oberon-class submarines served an important role as “clockwork mice” — targets for anti-submarine training exercises by Canadian and other Allied navies. After being equipped with passive sonar and Mark 48 torpedoes in the mid-1980s, these “O-boats” became true weapons platforms capable of performing their NATO missions in the Canadian Atlantic Submarine area. (Not until 2009 did the public learn of the “surreal moment” in late November 1986 during which Lieutenant-Commander Larry Hickey worked out the coordinates that, had he detected an offensive move, would have guided a torpedo from HMCS Onondaga into the hull of a nearby Soviet submarine — and possibly precipitated World War III.)

[…]

Last October, at the Naval Association of Canada conference in Ottawa, speaker after speaker lamented the public’s ignorance of these topics and, in many cases, its outright hostility toward submarines. Frigates, with their flared bows and graceful lines, intercept pirates in the Arabian Sea and hurry supplies to disaster areas after earthquakes and tsunamis. They sail to Toronto for the Canadian National Exhibition and make for good photo ops while passing under Vancouver’s Lions Gate Bridge. Part of the image problem, one speaker wryly noted, is that “you can’t host a decent cocktail party on the deck of a submarine.” Nor can the Victoria-class subs assert Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic in the muscular terms employed by Stephen Harper in his 2007 “Use It or Lose It” speech.

The submarine’s most important characteristic is its stealth. Far from being appreciated as a strategic asset, however, stealth jars with the public’s notion of a peaceable kingdom. Former foreign affairs minister Lloyd Axworthy went so far as to declare the ships “un-Canadian,” echoing British admiral Sir Arthur Wilson’s 1901 comment that they are “underhanded, unfair, and damned un-English.” According to Commander Michael Craven, gathering intelligence, joining with coalition partners to close off choke points, enabling “covert delivery and recovery of Special Operations Forces,” and performing a constabulary role against illegal fisheries and drug smugglers is exactly consistent with what Axworthy called “soft power.” That is, global influence exerted via “ideas, values, persuasion, skill and technique” and other forms of “non-intrusive intervention.”

February 26, 2015

Are submarines facing premature obsolescence?

Harry J. Kazianis looks at the risk for the US Navy as underwater detection systems become cheaper and more effective:

What would happen if U.S. nuclear attack submarines — some of the most sophisticated and expensive American weapons of war — suddenly became obsolete? Imagine a scenario where these important systems became the hunted instead of the hunter, or just as technologically backward as the massive battleships of years past. Think that sounds completely insane? If advances in big data and new detection methods fuse with the anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) ambitions of nations like China and Russia, naval planners around the world might have to go back to the drawing board.

Submarines: The New Battleship?

The revelation is alluded to in a recent report by the Washington, D.C.–based Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) called “The Emerging Era in Undersea Warfare.” Smartly named by a certain TNI editor as the “think-tank’s think-tank,” CSBA has crafted in the last decade many of the most detailed and sophisticated reports regarding the most pressing national-security challenges around — sometimes years before anyone else. Ever heard of a little operational concept called AirSea Battle? They were at the forefront of it before it was in the news.

In a piece for TNI, the report’s author, Bryan Clark, lays out the problem in more layman’s terms:

Since the Cold War submarines, particularly quiet American ones, have been considered largely immune to adversary A2/AD capabilities. But the ability of submarines to hide through quieting alone will decrease as each successive decibel of noise reduction becomes more expensive and as new detection methods mature that rely on phenomena other than sounds emanating from a submarine. These techniques include lower frequency active sonar and non-acoustic methods that detect submarine wakes or (at short ranges) bounce laser or light-emitting diode (LED) light off a submarine hull. The physics behind most of these alternative techniques has been known for decades, but was not exploited because computer processors were too slow to run the detailed models needed to see small changes in the environment caused by a quiet submarine. Today, “big data” processing enables advanced navies to run sophisticated oceanographic models in real time to exploit these detection techniques. As they become more prevalent, they could make some coastal areas too hazardous for manned submarines.

Could modern attack subs soon face the same problem as surface combatants around the world, where some areas are simply too dangerous to enter, thanks to pressing A2/AD challenges?