Published on 20 Jun 2016

Special thanks to Karim Theilgaard for composing the the new theme for our brand new intro!

We are approaching the 100th regular episode and decided to surprise you with an extra special episode about the staggering numbers of World War 1.

June 21, 2016

World War 1 in Numbers I THE GREAT WAR Special

May 26, 2016

Eighty percent of Americans surveyed favour banning things they know nothing about

Don’t get too smug, fellow Canuckistanis, as I suspect the numbers might be just as bad if Canadians were surveyed in this way:

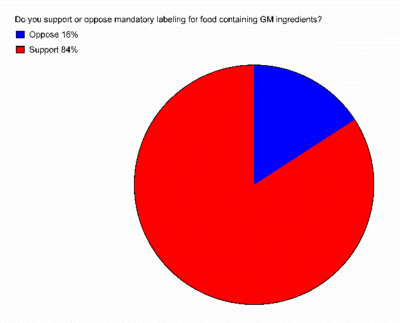

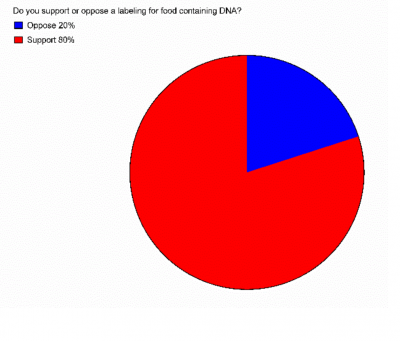

You might have heard that Americans overwhelmingly favor mandatory labeling for foods containing genetically modified ingredients. That’s true, according to a new study: 84 percent of respondents said they support the labels.

But a nearly identical percentage — 80 percent—in the same survey said they’d also like to see labels on food containing DNA.

The study, published in the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology Journal last week, also found that 33 percent of respondents thought that non-GM tomatoes “did not contain genes” and 32 percent thought that “vegetables did not have DNA.” So there’s that.

University of Florida food economist Brandon R. McFadden and his co-author Jayson L. Lusk surveyed 1,000 American consumers and discovered [PDF] that “consumers think they know more than they actually do about GM food.” In fact, the authors say, “the findings question the usefulness of results from opinion polls as motivation for public policy surrounding GM food.”

My summary for laymen: When it comes to genetically modified food, people don’t know much, they don’t know what they don’t know, and they sure as heck aren’t letting that stop them from having strong opinions.

April 24, 2016

The “secret” of Indian food

In an article in the Washington Post last year, Roberto Ferdman summarized the findings of a statistical study explaining why the flavours in Indian foods differ so much from other world cuisines:

Indian food, with its hodgepodge of ingredients and intoxicating aromas, is coveted around the world. The labor-intensive cuisine and its mix of spices is more often than not a revelation for those who sit down to eat it for the first time. Heavy doses of cardamom, cayenne, tamarind and other flavors can overwhelm an unfamiliar palate. Together, they help form the pillars of what tastes so good to so many people.

But behind the appeal of Indian food — what makes it so novel and so delicious — is also a stranger and subtler truth. In a large new analysis of more than 2,000 popular recipes, data scientists have discovered perhaps the key reason why Indian food tastes so unique: It does something radical with flavors, something very different from what we tend to do in the United States and the rest of Western culture. And it does it at the molecular level.

[…]

Chefs in the West like to make dishes with ingredients that have overlapping flavors. But not all cuisines adhere to the same rule. Many Asian cuisines have been shown to belie the trend by favoring dishes with ingredients that don’t overlap in flavor. And Indian food, in particular, is one of the most powerful counterexamples.

Researchers at the Indian Institute for Technology in Jodhpur crunched data on several thousand recipes from a popular online recipe site called TarlaDalal.com. They broke each dish down to its ingredients, and then compared how often and heavily ingredients share flavor compounds.

The answer? Not too often.

November 29, 2015

Does Teddy Bridgewater hold the ball too long?

Over at Vikings Territory, Brett Anderson endangers his health, eyesight, and even his sanity by exhaustively tracking, timing, and analyzing every throw by Teddy Bridgewater in last week’s game against the Green Bay Packers. A common knock on Bridgewater is that he’s holding the ball too long and therefore missing pass opportunities and making himself more vulnerable to being sacked. It’s a long article, but you can skip right to the end to get the facts distilled:

Over at Vikings Territory, Brett Anderson endangers his health, eyesight, and even his sanity by exhaustively tracking, timing, and analyzing every throw by Teddy Bridgewater in last week’s game against the Green Bay Packers. A common knock on Bridgewater is that he’s holding the ball too long and therefore missing pass opportunities and making himself more vulnerable to being sacked. It’s a long article, but you can skip right to the end to get the facts distilled:

What The Film Shows

It became clear pretty quickly that plays with larger TBH [time ball held] had a lot happening completely out of Bridgewater’s control. There were only a couple of plays where it clearly looked like Bridgewater held the ball too long while there were options downfield to target or that he hesitated to pull the trigger on guys that were open. And consistently, there were three issues I kept noticing.

- Receiver route depth – The Vikings receivers run a ton of late developing routes. I don’t have any numbers to back that up – we’re talking strictly film review now. But on plays ran out of the shotgun with 5-step drops or plays with even longer 7-step drops, by the time Bridgewater is being pressured (which happens about every 2 of 3 plays), his receivers have not finished their routes. And I know that just because they haven’t finished the route doesn’t mean Bridgewater can’t anticipate where they are going to be but… We’re talking not really even close to finishing their routes. It seems that a lot of the Vikings play designs consist of everybody running deep fade routes to create room underneath for someone on a short dig or to check down to a running back in the flat. So, if this player underneath is for any reason covered (or if the Vikings find themselves in long down and distance situations where an underneath route isn’t going to cut it, which… surprise, happens quite often), Bridgewater’s other receiver options are midway through their route 20 yards downfield. What’s worse? Not only are these routes taking forever to develop and typically only materializing once Bridgewater has been sacked or scampered away to save himself, but also…

- Receiver coverage – The Vikings receivers are typically not open. It was pretty striking how often on plays with higher TBH receivers have very little separation. (Make sure to take a look through the frame stills linked in the data table above. I tried to make sure I provided a capture for plays with higher TBH or plays that resulted in a negative outcome. Red circles obviously indicate receivers who are not open while yellow typically indicates receivers who are.) The Packers consistently had 7 defenders in coverage resulting in multiple occasions where multiple receivers are double teamed with safety help over the top. But even in plays with one on one coverage, the Vikings receivers are still having a difficult time finding space. So now, we have a situation with Bridgewater where we have these deep drops where not only are receivers not finished with their deep routes but they are also blanket covered. And why are teams able to drop so many players into coverage creating risky situations for a quarterback who is consistently risk adverse? Because…

- Poor offensive line play – The Vikings offensive line is not good. And it may be worse than you think. It’s no secret by this point that the Vikings offensive line had one of its worst showings of the year against the Packers. More often than not, simply by rushing four defenders, Green Bay was able to get pressure on Bridgewater within 2-3 seconds. This is a quick sack time. And more often than not, Bridgewater is having to evade this pressure by any means necessary to either give his receivers time to finish their routes or give them time to get open. (Or more frequently – both.) As a result of this, what we saw on multiple occasions against the Packers is Bridgewater being pressured quickly, him scrambling from the pocket and dancing around while stiff-arming a defender once or twice and ultimately throwing the ball out of bounds or taking a sack. Are you starting to see what the problem here?

Conclusion

Bridgewater is not holding the ball for a length of time that should reflect poorly on his play. The data shows that Bridgewater is about average when looking just strictly at the numbers. The tape shows a quarterback who really doesn’t have a lot of options other than holding on to the ball. When Bridgewater is presented with a quick 1- or 3-step drop and his receivers run routes with lengths complementary to the length of his drop, it typically results in Bridgewater finding a relatively open receiver, making a quick decision and getting the ball there accurately. When Bridgewater is faced with longer developing plays behind an offensive line that’s a sieve and receivers who are running lengthy routes while closely covered, he tries to make a play himself. Sure, there were a couple of plays during the Packers game where it may have been a better decision for Bridgewater to take a sack when initially pressured and saving the yards he lost by scrambling backwards. However, it’s difficult to chastise him for trying to create plays when they aren’t there when it doesn’t work and applauding him when his evasiveness, deadly stiff arm and surprisingly effective spin move result in a big play.

Bridgewater has been far from perfect this season. But after this extensive exercise, I can comfortably say that the amount of time Bridgewater is holding on to the ball should not negatively reflect on his performance considering the above mentioned external factors.

November 27, 2015

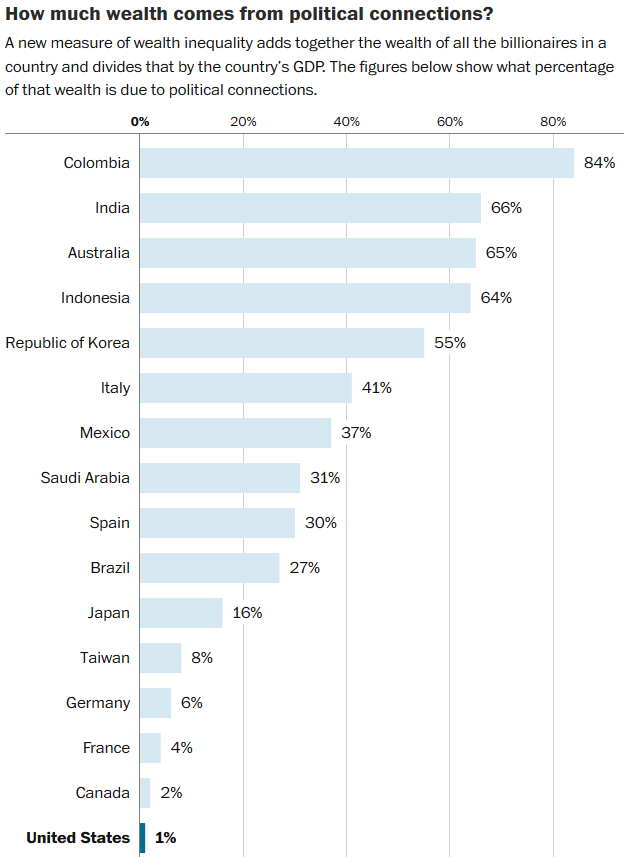

Wealth, inequality, and billionaires

Several months ago, the Washington Post reported on a new study of wealth and inequality that tracked how many billionaires got rich through competition in the market and how many got rich through political “connections”:

The researchers found that wealth inequality was growing over time: Wealth inequality increased in 17 of the 23 countries they measured between 1987 and 2002, and fell in only six, Bagchi says. They also found that their measure of wealth inequality corresponded with a negative effect on economic growth. In other words, the higher the proportion of billionaire wealth in a country, the slower that country’s growth. In contrast, they found that income inequality and poverty had little effect on growth.

The most fascinating finding came from the next step in their research, when they looked at the connection between wealth, growth and political connections.

The researchers argue that past studies have looked at the level of inequality in a country, but not why inequality occurs — whether it’s a product of structural inequality, like political power or racism, or simply a product of some people or companies faring better than others in the market. For example, Indonesia and the United Kingdom actually score similarly on a common measure of inequality called the Gini coefficient, say the authors. Yet clearly the political and business environments in those countries are very different.

So Bagchi and Svejnar carefully went through the lists of all the Forbes billionaires, and divided them into those who had acquired their wealth due to political connections, and those who had not. This is kind of a slippery slope — almost all billionaires have probably benefited from government connections at one time or another. But the researchers used a very conservative standard for classifying people as politically connected, only assigning billionaires to this group when it was clear that their wealth was a product of government connections. Just benefiting from a government that was pro-business, like those in Singapore and Hong Kong, wasn’t enough. Rather, the researchers were looking for a situation like Indonesia under Suharto, where political connections were usually needed to secure import licenses, or Russia in the mid-1990s, when some state employees made fortunes overnight as the state privatized assets.

The researchers found that some countries had a much higher proportion of billionaire wealth that was due to political connections than others did. As the graph below, which ranks only countries that appeared in all four of the Forbes billionaire lists they analyzed, shows, Colombia, India, Australia and Indonesia ranked high on the list, while the U.S. and U.K. ranked very low.

Looking at all the data, the researchers found that Russia, Argentina, Colombia, Malaysia, India, Australia, Indonesia, Thailand, South Korea and Italy had relatively more politically connected wealth. Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland and the U.K. all had zero politically connected billionaires. The U.S. also had very low levels of politically connected wealth inequality, falling just outside the top 10 at number 11.

When the researchers compared these figures to economic growth, the findings were clear: These politically connected billionaires weighed on economic growth. In fact, wealth inequality that came from political connections was responsible for nearly all the negative effect on economic growth that the researchers had observed from wealth inequality overall. Wealth inequality that wasn’t due to political connections, income inequality and poverty all had little effect on growth.

November 14, 2015

The scandal of NCAA “graduation” rates

Gregg Easterbrook on the statistical sleight-of-hand that allows US universities to claim unrealistic graduation rates for their student athletes:

N.C.A.A. Graduation Rate Hocus-Pocus. [Hawaii coach Norm] Chow and [Maryland coach Randy] Edsall both made bona fide improvements to the educational quality of their college football programs, and both were fired as thanks. Edsall raised Maryland’s football graduation rate from 56 percent five years ago to 70 percent. Chow raised Hawaii’s football graduation rate from 29 percent five years ago to 50 percent.

At least that’s what the Department of Education says. According to the N.C.A.A., Hawaii graduates not 50 percent of its players but 70 percent, while Maryland graduates not 70 percent but 75 percent.

At work is the distinction between the Federal Graduation Rate, calculated by the Department of Education, and the Graduation Success Rate, calculated by the N.C.A.A. No other aspect of higher education has a graduation “success rate” — just a graduation rate. The N.C.A.A. cooks up this number to make the situation seem better than it is.

The world of the Graduation Success Rate is wine and roses: According to figures the N.C.A.A. released last week, 86 percent of N.C.A.A. athletes achieved “graduation success” in the 2014-2015 academic year. But “graduation success” is different from graduating; the Department of Education finds that 67 percent of scholarship athletes graduated in 2014-2015. (These dueling figures are for all scholarship athletes: Football and men’s basketball players generally are below the average, those in other sports generally above.)

Both the federal and N.C.A.A. calculations have defects. The federal figure scores only those who graduate from the college of their initial enrollment. The athlete who transfers and graduates elsewhere does not count in the federal metric.

The G.S.R., by contrast, scores as a “graduate” anyone who leaves a college in good standing, via transfer or simply giving up on school: There’s no attempt to follow-up to determine whether athletes who leave graduate somewhere else. Not only is the N.C.A.A.’s graduation metric anchored in the absurd assumption that leaving a college is the same as graduating, but it can also reflect a double-counting fallacy. Suppose a football player starts at College A, transfers to College B and earns his diploma there. Both schools count him as a graduate under the G.S.R.

[…]

Football players ought to graduate at a higher rate than students as a whole. Football scholarships generally pay for five years on campus plus summer school, and football scholarship holders never run out of tuition money, which is the most common reason students fail to complete college. Instead at Ohio State and other money-focused collegiate programs, players graduate at a lower rate than students as a whole. To divert attention from this, the N.C.A.A. publishes its annual hocus-pocus numbers.

October 28, 2015

The WHO’s lack of clarity leads to sensationalist newspaper headlines (again)

The World Health Organization appears to exist primarily to give newspaper editors the excuse to run senational headlines about the risk of cancer. This is not a repeat story from earlier years. Oh, wait. Yes it is. Here’s The Atlantic‘s Ed Yong to de-sensationalize the recent scary headlines:

The International Agency of Research into Cancer (IARC), an arm of the World Health Organization, is notable for two things. First, they’re meant to carefully assess whether things cause cancer, from pesticides to sunlight, and to provide the definitive word on those possible risks.

Second, they are terrible at communicating their findings.

[…]

Group 1 is billed as “carcinogenic to humans,” which means that we can be fairly sure that the things here have the potential to cause cancer. But the stark language, with no mention of risks or odds or any remotely conditional, invites people to assume that if they specifically partake of, say, smoking or processed meat, they will definitely get cancer.

Similarly, when Group 2A is described as “probably carcinogenic to humans,” it roughly translates to “there’s some evidence that these things could cause cancer, but we can’t be sure.” Again, the word “probably” conjures up the specter of individual risk, but the classification isn’t about individuals at all.

Group 2B, “possibly carcinogenic to humans,” may be the most confusing one of all. What does “possibly” even mean? Proving a negative is incredibly difficult, which is why Group 4 — “probably not carcinogenic to humans” — contains just one substance of the hundreds that IARC has assessed.

So, in practice, 2B becomes a giant dumping ground for all the risk factors that IARC has considered, and could neither confirm nor fully discount as carcinogens. Which is to say: most things. It’s a bloated category, essentially one big epidemiological shruggie. But try telling someone unfamiliar with this that, say, power lines are “possibly carcinogenic” and see what they take away from that.

Worse still, the practice of lumping risk factors into categories without accompanying description — or, preferably, visualization — of their respective risks practically invites people to view them as like-for-like. And that inevitably led to misleading headlines like this one in the Guardian: “Processed meats rank alongside smoking as cancer causes – WHO.”

October 15, 2015

S.L.A. Marshall, Dave Grossman, and the “man is naturally peaceful” meme

The American military historian S.L.A. Marshall was perhaps best known for his book Men Against Fire: The Problem of Battle Command in Future War, where he argued that American military training was insufficient to overcome most men’s natural hesitation to take another human life, even in intense combat situations. Dave Grossman is a modern military author who draws much of his conclusions from the initial work of Marshall. Grossman’s case is presented in his book On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, which was reviewed by Robert Engen in an older issue of the Canadian Military Journal:

As a military historian, I am instinctively skeptical of any work or theory that claims to overturn all existing scholarship – indeed, overturn an entire academic discipline – in one fell swoop. In academic history, the field normally expands and evolves incrementally, based upon new research, rather than being completely overthrown periodically. While it is not impossible for such a revolution to take place and become accepted, extraordinary new research and evidence would need to be presented to back up these claims. Simply put, Grossman’s On Killing and its succeeding “killology” literature represent a potential revolution for military history, if his claims can stand up to scrutiny – especially the claim that throughout human history, most soldiers and people have been unable to kill one another.

I will be the first to acknowledge that Grossman has made positive contributions to the discipline. On Combat, in particular, contains wonderful insights on the physiology of combat that bear further study and incorporation within the discipline. However, Grossman’s current “killology” literature contains some serious problems, and there are some worrying flaws in the theories that are being preached as truth to the men and women of the Canadian Forces. Although much of Grossman’s work is credible, his proposed theories on the inability of human beings to kill one another, while optimistic, are not sufficiently reinforced to warrant uncritical acceptance. A reassessment of the value that this material holds for the Canadian military is necessary.

The evidence seems to indicate that, contrary to Grossman’s ideas, killing is a natural, if difficult, part of human behaviour, and that killology’s belief that soldiers and the population at large are only being able to kill as part of programmed behaviour (or as a symptom of mental illness) hinders our understanding of the actualities of warfare. A flawed understanding of how and why soldiers can kill is no more helpful to the study of military history than it is to practitioners of the military profession. More research in this area is required, and On Killing and On Combat should be treated as the starting points, rather than the culmination, of this process.

September 5, 2015

The subtle lure of “research” that confirms our biases

Megan McArdle on why we fall for bogus research:

Almost three years ago, Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman penned an open letter to researchers working on “social priming,” the study of how thoughts and environmental cues can change later, mostly unrelated behaviors. After highlighting a series of embarrassing revelations, ranging from outright fraud to unreproducible results, he warned:

For all these reasons, right or wrong, your field is now the poster child for doubts about the integrity of psychological research. Your problem is not with the few people who have actively challenged the validity of some priming results. It is with the much larger population of colleagues who in the past accepted your surprising results as facts when they were published. These people have now attached a question mark to the field, and it is your responsibility to remove it.

At the time it was a bombshell. Now it seems almost delicate. Replication of psychology studies has become a hot topic, and on Thursday, Science published the results of a project that aimed to replicate 100 famous studies — and found that only about one-third of them held up. The others showed weaker effects, or failed to find the effect at all.

This is, to put it mildly, a problem. But it is not necessarily the problem that many people seem to assume, which is that psychology research standards are terrible, or that the teams that put out the papers are stupid. Sure, some researchers doubtless are stupid, and some psychological research standards could be tighter, because we live in a wide and varied universe where almost anything you can say is certain to be true about some part of it. But for me, the problem is not individual research papers, or even the field of psychology. It’s the way that academic culture filters papers, and the way that the larger society gets their results.

August 29, 2015

We need a new publication called The Journal of Successfully Reproduced Results

We depend on scientific studies to provide us with valid information on so many different aspects of life … it’d be nice to know that the results of those studies actually hold up to scrutiny:

One of the bedrock assumptions of science is that for a study’s results to be valid, other researchers should be able to reproduce the study and reach the same conclusions. The ability to successfully reproduce a study and find the same results is, as much as anything, how we know that its findings are true, rather than a one-off result.

This seems obvious, but in practice, a lot more work goes into original studies designed to create interesting conclusions than into the rather less interesting work of reproducing studies that have already been done to see whether their results hold up.

Everyone wants to be part of the effort to identify new and interesting results, not the more mundane (and yet potentially career-endangering) work of reproducing the results of older studies:

Why is psychology research (and, it seems likely, social science research generally) so stuffed with dubious results? Let me suggest three likely reasons:

A bias towards research that is not only new but interesting: An interesting, counterintuitive finding that appears to come from good, solid scientific investigation gets a researcher more media coverage, more attention, more fame both inside and outside of the field. A boring and obvious result, or no result, on the other hand, even if investigated honestly and rigorously, usually does little for a researcher’s reputation. The career path for academic researchers, especially in social science, is paved with interesting but hard to replicate findings. (In a clever way, the Reproducibility Project gets around this issue by coming up with the really interesting result that lots of psychology studies have problems.)

An institutional bias against checking the work of others: This is the flipside of the first factor: Senior social science researchers often actively warn their younger colleagues — who are in many cases the best positioned to check older work—against investigating the work of established members of the field. As one psychology professor from the University of Southern California grouses to the Times, “There’s no doubt replication is important, but it’s often just an attack, a vigilante exercise.”

[…]

Small, unrepresentative sample sizes: In general, social science experiments tend to work with fairly small sample sizes — often just a few dozen people who are meant to stand in for everyone else. Researchers often have a hard time putting together truly representative samples, so they work with subjects they can access, which in a lot of cases means college students.

A couple of years ago, I linked to a story about the problem of using western university students as the default source of your statistical sample for psychological and sociological studies:

A notion that’s popped up several times in the last couple of months is that the easy access to willing test subjects (university students) introduces a strong bias to a lot of the tests, yet until recently the majority of studies disregarded the possibility that their test results were unrepresentative of the general population.

August 19, 2015

Canada looks very good on an international ranking you won’t hear about from our media

Our traditional media are quick to pump up the volume for “studies” that find that we rank highly on various rankings of cities or what-have-you, but here’s someone pointing out that Canada’s ranking is quite good, but it’s not the kind of measurement our media want to encourage or publicize:

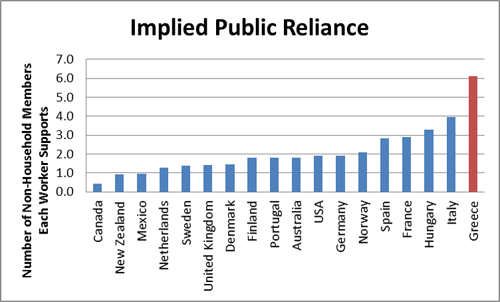

First, we must identify a nation’s currently employed population. Next, all public sector employees are removed to obtain an adjusted productive workforce. It may be objectionable that certain professions, like teaching, nurses in single payer systems and fire fighters, are classified as an unproductive workforce, but as our system is currently designed, the salaries of these individuals are not covered by the immediate beneficiaries like any other business but are paid through dispersed taxation methods.

Finally, this productive population is divided into the nation’s total population to identify the total number of individuals a worker is expected to support in his country. To remove bias toward non-working spouses and children, the average household size is subtracted from this result to get the final number of individuals that an individual must support that are not part of their own voluntary household. In other words, how many total strangers is this individual providing for?

The Implied Public Reliance metric does a far better job of predicting economic performance:

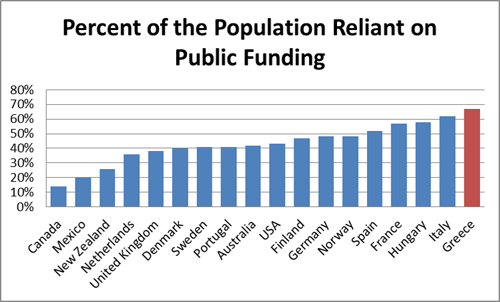

Greece, the nation with the debt problem, is currently expecting each employed person to support 6.1 other people above and beyond their own families. This explains much of the pressure to work long hours and also explains the unstable debt loads. Since a single Greek worker can’t possibly hope to support what amounts to a complete baseball team on a single salary, the difference is covered by Greek public debt, debt that the underlying social system cannot hope to repay as the incentives are to maintain the current system of subsidies. To demonstrate how difficult it is to change these systems within a democratic society, we just have to look at the percentage of the population that is reliant on public subsidy.

Oh, and by the way … Greece is doomed:

The numbers imply that 67 percent of the population of Greece is wholly reliant on the Greek government to provide their incomes. With such a commanding supermajority, changing this system with the democratic process is impossible as the 67 percent have strong incentives to continue to vote for the other 33 percent — and also foreign entities — to cover their living expenses.

August 15, 2015

Science in the media – from “statistical irregularities” to outright fraud

In The Atlantic, Bourree Lam looks at the state of published science and how scientists can begin to address the problems of bad data, statistical sleight-of-hand, and actual fraud:

In May, the journal Science retracted a much-talked-about study suggesting that gay canvassers might cause same-sex marriage opponents to change their opinion, after an independent statistical analysis revealed irregularities in its data. The retraction joined a string of science scandals, ranging from Andrew Wakefield’s infamous study linking a childhood vaccine and autism to the allegations that Marc Hauser, once a star psychology professor at Harvard, fabricated data for research on animal cognition. By one estimate, from 2001 to 2010, the annual rate of retractions by academic journals increased by a factor of 11 (adjusting for increases in published literature, and excluding articles by repeat offenders). This surge raises an obvious question: Are retractions increasing because errors and other misdeeds are becoming more common, or because research is now scrutinized more closely? Helpfully, some scientists have taken to conducting studies of retracted studies, and their work sheds new light on the situation.

“Retractions are born of many mothers,” write Ivan Oransky and Adam Marcus, the co-founders of the blog Retraction Watch, which has logged thousands of retractions in the past five years. A study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reviewed 2,047 retractions of biomedical and life-sciences articles and found that just 21.3 percent stemmed from straightforward error, while 67.4 percent resulted from misconduct, including fraud or suspected fraud (43.4 percent) and plagiarism (9.8 percent).

Surveys of scientists have tried to gauge the extent of undiscovered misconduct. According to a 2009 meta-analysis of these surveys, about 2 percent of scientists admitted to having fabricated, falsified, or modified data or results at least once, and as many as a third confessed “a variety of other questionable research practices including ‘dropping data points based on a gut feeling,’ and ‘changing the design, methodology or results of a study in response to pressures from a funding source’”.

As for why these practices are so prevalent, many scientists blame increased competition for academic jobs and research funding, combined with a “publish or perish” culture. Because journals are more likely to accept studies reporting “positive” results (those that support, rather than refute, a hypothesis), researchers may have an incentive to “cook” or “mine” their data to generate a positive finding. Such publication bias is not in itself news — back in 1987, a study found that, compared with research trials that went unpublished, those that were published were three times as likely to have positive results. But the bias does seem to be getting stronger: a more recent study of 4,600 research papers found that from 1990 to 2007, the proportion of positive results grew by 22 percent.

August 3, 2015

Undependable numbers in the campus rape debate

Megan McArdle on the recently revealed problems in one of the most frequently used set of statistics on campus rape:

… a new article in Reason magazine suggests that this foundation is much shakier than most people working on this issue — myself included — may have assumed. (Full disclosure: the Official Blog Spouse is an editor at Reason.) The author, Linda M. LeFauve, looked carefully at the study, including conducting an interview with Lisak, and identified multiple issues:

- Lisak did not actually do original research. Instead, he pooled data from studies that were not necessarily aimed at collecting data on college students, or indeed, about rape. Only five questions on a multi-page questionnaire asked about sexual violence that they may have committed as adults, against other adults.

- The campus where this data was collected is a commuter campus. It’s not clear that everyone surveyed was a college student, but if so, the sample included many non-traditional students, with an average age of 26.5. Yet this data has been widely applied to traditional campuses, even though the two populations may differ greatly.

- The responses indicate that the men identified as rapists were extraordinarily more violent than the normal population: “The high rate of other forms of violence reported by the men in Lisak’s paper further suggests they are an atypical group. Of the 120 subjects Lisak classified as rapists, 46 further admitted to battery of an adult, 13 to physical abuse of a child, 21 to sexual abuse of a child, and 70 — more than half the group — to other forms of criminal violence. By itself, the nearly 20 percent who had sexually abused a child should signal that this is not a group from whom it is reasonable to generalize findings to a college campus.”

- The data did not cover acts committed while in college, but any acts of sexual violence; a number of them seem to have been committed in domestic violence situations.

- Lisak appears to have exaggerated how much follow-up he was able to do on the people he surveyed, at least to LeFauve: “Lisak told me that he subsequently interviewed most of them. That was a surprising claim, given the conditions of the survey and the fact that he was looking at the data produced long after his students had completed those dissertations; nor were there plausible circumstances under which a faculty member supervising a dissertation would interact directly with subjects. When I asked how he was able to speak with men participating in an anonymous survey for research he was not conducting, he ended the phone call.” Robby Soave of Reason, in a companion piece, also raises doubts about Lisak’s repeated assertions that he conducted extensive follow-ups with “most” of the respondents to what were mostly anonymous surveys.

In short, Lisak’s 2002 study is not a systematic survey of rape on campus; it is pooled data from surveys of people who happen to have been near a commuter campus on days when the surveys were being collected.

Before I go any further, let me note that I’m not saying that what these men did was not bad, or does not deserve to be punished. But if LeFauve is right, this study is basically worthless for shaping campus policies designed to stop rape.

July 27, 2015

The “Ferguson Effect”

Radley Balko explains why the concerns and worries of police officials have been totally upheld by the rising tide of violence against police officers in the wake of the events in Ferguson … oh, wait. No, that’s not what happened at all:

The “Ferguson effect,” you might remember, is a phenomenon law-and-order types have been throwing around in an effort to blame police brutality on protesters and public officials who actually try to hold bad cops accountable for an alleged increase in violence, both general violence and violence against police officers.

The problem is that there’s no real evidence to suggest it exists. As I and others pointed out in June, while there have been some increases in crime in a few cities, including Baltimore and St. Louis County, there’s just no empirical data to support the notion that we’re in the middle of some national crime wave. And while there was an increase in killings of police officers in 2014, that came after a year in which such killings were at a historic low. And in any case, the bulk of killings of police officers last year came before the Ferguson protests in August and well before the nationwide Eric Garner protests in December.

Now, the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund has released its mid-year report on police officers’ deaths in 2015. Through the end of June, the number of officers killed by gunfire has dropped 25 percent from last year, from 24 to 18. Two of those incidents were accidental shootings (by other cops), so the number killed by hostile gunfire is 16. (As of today, the news is even better: Police deaths due to firearms through July 23 are down 30 percent from last year.)

[…]

A typical officer on a typical stop is far more likely to die of a heart attack than to be shot by someone inside that car.

It’s important to note here that we’re also talking about very small numbers overall. Police officer deaths have been in such rapid decline since the 1990s that when taken as percentages, even statistical noise in the raw figures can look like a large swing one way or the other. And if we look at the rate of officer fatalities (as opposed to the raw data), the degree to which policing has gotten safer over the last 20 years is only magnified.

But the main takeaway from the first-half figures of 2015 is this: If we really were in the midst of a nationwide “Ferguson effect,” we’d expect to see attacks on police officers increasing. Instead, we’re seeing the opposite. That’s good news for cops. It’s bad news for people who want to blame protesters and reform advocates for the deaths of police officers.

June 22, 2015

Breaking – it’s a nation-wide crime wave (when you cherry-pick your data)

Daniel Bier looks at how Wall Street Journal contributor Heather Mac Donald concocted her data to prove that there’s a rising tide of crime across the United States:

Heather Mac Donald is back in the Wall Street Journal to defend her thesis that there is a huge national crime wave and that protesters and police reformers are to blame.

In her original piece, Mac Donald cherry picked whatever cities and whatever categories of crime showed an increase so far this year, stacked up all the statistics that supported her idea, ignored all the ones that didn’t, and concluded we are suffering a “nationwide crime wave.”

Of course, you could do this kind of thing any year to claim that crime is rising. But it isn’t.

The fifteen largest cities have seen a 2% net decrease in murder so far this year. Eight saw a rise in murder rates, and seven saw an even larger decline.

Guess which cities Mac Donald mentioned and which she did not.

This is how you play tennis without the net. Or lines.

And in her recent post, buried seven paragraphs in, comes this admission: “It is true that violent crime has not skyrocketed in every American city — but my article didn’t say it had.”

But neither did her article acknowledge that murder in big cities was falling overall — in fact, it didn’t acknowledge that murder or violent crime was declining anywhere. Apparently, in her view, it is acceptable to present a distorted view of the data as long as it isn’t an outright lie.