Thirty years ago, the Princeton philosopher Harry Frankfurt published an essay in an obscure academic journal, Raritan. The essay’s title was “On Bullshit”. (Much later, it was republished as a slim volume that became a bestseller.) Frankfurt was on a quest to understand the meaning of bullshit — what was it, how did it differ from lies, and why was there so much of it about?

Frankfurt concluded that the difference between the liar and the bullshitter was that the liar cared about the truth — cared so much that he wanted to obscure it — while the bullshitter did not. The bullshitter, said Frankfurt, was indifferent to whether the statements he uttered were true or not. “He just picks them out, or makes them up, to suit his purpose.”

Statistical bullshit is a special case of bullshit in general, and it appears to be on the rise. This is partly because social media — a natural vector for statements made purely for effect — are also on the rise. On Instagram and Twitter we like to share attention-grabbing graphics, surprising headlines and figures that resonate with how we already see the world. Unfortunately, very few claims are eye-catching, surprising or emotionally resonant because they are true and fair. Statistical bullshit spreads easily these days; all it takes is a click.

Tim Harford, “How politicans poisoned statistics”, TimHarford.com, 2016-04-20.

January 8, 2018

January 1, 2018

Blog traffic in 2017

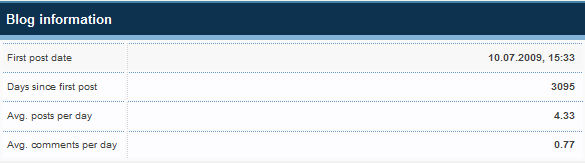

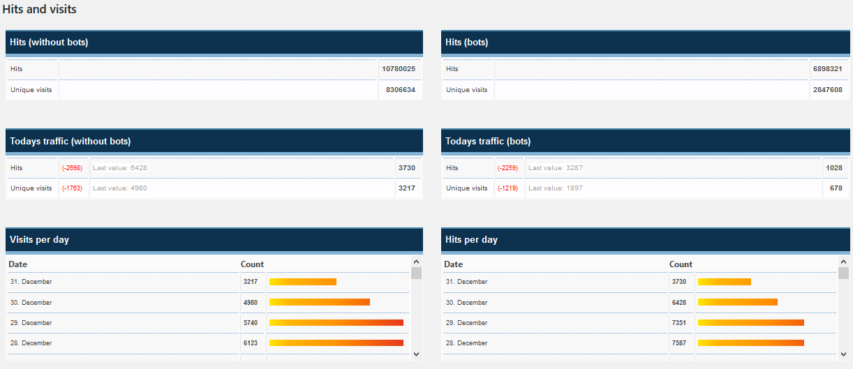

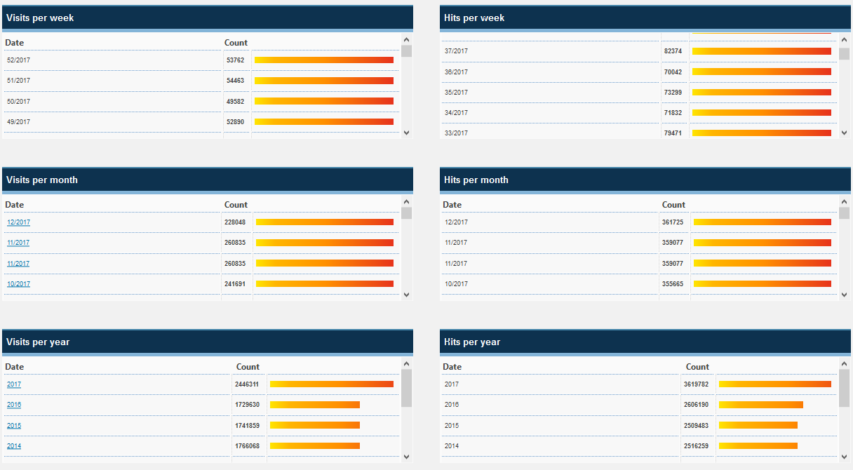

The annual statistics update on Quotulatiousness from January 1st through December 31st, 2017. The numbers will be a couple of thousand short of the full year, as I did the screen captures mid-morning on the 31st.

I stopped paying much attention to the blog stats years ago, but the jump in traffic from 2016 to 2017 is amazing! Going from a stable ~1.7 million visits per year to nearly 2.5 million last year is quite unexpected. That’s getting up toward the region where it might seem to make sense to try to monetize the blog … but I tried doing the Amazon affiliate thing earlier this year, and it generated exactly $0.00 in revenue for Amazon, and I got my full share of that revenue (as Jayne put it: “Let’s see, let me do the math: 10 per cent of nothing is, … (mumble) carry the zero …(mumble) … “)

October 26, 2017

QotD: The nutrition science is settled

Nutrition science is, in general, a bottomless stew of politics, guesswork, bogus data and poor statistical practice. I would call it “unsavoury” if that weren’t such an inexcusable pun in this context. Anyone who has read the newspaper for 10 or 20 years, watching the endless tide of good-for-you/bad-for-you roll in and out, must know this instinctively.

Colby Cosh, “MSG: The harmless food enhancer everyone still dreads”, National Post, 2016-04-18.

September 5, 2017

The 100 Year Flood Is Not What You Think It Is (Maybe)

Published on 6 Mar 2016

Today on Practical Engineering we’re talking about hydrology, and I took a little walk through my neighborhood to show you some infrastructure you may have never noticed before.

Almost everyone agrees that flooding is bad. Most years it’s the number one natural disaster in the US by dollars of damage. So being able to characterize flood risks is a crucial job of civil engineers. Engineering hydrology has equal parts statistics and understanding how society treats risks. Water is incredibly important to us, and it shapes almost every facet of our lives, but it’s almost never in the right place at the right time. Sometimes there’s not enough, like in a drought or just an arid region, but we also need to be prepared for the times when there’s too much water, a flood. Rainfall and streamflow have tremendous variability and it’s the engineer’s job to characterize that so that we can make rational and intelligent decisions about how we develop the world around us. Thanks for watching!

FEMA Floodplain Maps: https://msc.fema.gov/portal

USGS Stream Gages: http://maps.waterdata.usgs.gov/mapper

“So, let’s consider the concept of a ‘500-year flood'”

Charlie Martin explains how it’s possible to have two “500-year floods” in less than 500 years:

There have been a lot of people suggesting that Harvey the Hurricane shows that “really and truly climate change is happening, see, in-your-face deniers!”

Of course, it’s possible, even though the actual evidence — including the 12-year drought in major hurricanes — is against it. But hurricanes are a perfect opportunity for stupid math tricks. Hurricanes also provide great opportunities to explain concepts that are unclear to people. So, let’s consider the concept of a “500-year flood.”

Most people hear this and think it means “one flood this size in 500 years.” The real definition is subtly different: saying “a 500-year flood” actually means “there is one chance in 500 of a flood this size happening in any year.”

It’s called a “500-year flood” because statistically, over a long enough time, we would expect to have roughly one such flood on average every 500 years. So, if we had 100,000 years of weather data (and things stayed the same otherwise, which is an unrealistic assumption) then we’d expect to have seen 100,000/500- or 200 500-year floods [Ed. typo fixed] at that level.

The trouble is, we’ve only got about 100 years of good weather data for the Houston area.

July 27, 2017

Words & Numbers: Is Income Inequality Real?

Published on 26 Jul 2017

Income inequality has been in the news more and more, and it doesn’t look good. It’s aggravating to see people making more money than you, and we’re told all the time that income inequality is on the rise. But is it? And even if it is, is it actually a bad thing? This week on Words and Numbers, Antony Davies and James R. Harrigan talk about how income inequality plays out in the real world.

Learn more: https://fee.org/articles/is-income-inequality-real/

July 19, 2017

“The Economics of Trade” | THINK 2017

Published on Jul 17, 2017

What exactly is Free Trade and is it always the best policy?

Professor Don Boudreaux of Cafe Hayek discusses the morality of capitalist exchange and its inherent advantages.

July 13, 2017

“Each month in the United States—a place with about 160 million civilian jobs—1.7 million of them vanish”

Deirdre McCloskey addresses the fear that technological change is gobbling up all the jobs:

Consider the historical record: If the nightmare of technological unemployment were true, it would already have happened, repeatedly and massively. In 1800, four out of five Americans worked on farms. Now one in 50 do, but the advent of mechanical harvesting and hybrid corn did not disemploy the other 78 percent.

In 1910, one out of 20 of the American workforce was on the railways. In the late 1940s, 350,000 manual telephone operators worked for AT&T alone. In the 1950s, elevator operators by the hundreds of thousands lost their jobs to passengers pushing buttons. Typists have vanished from offices. But if blacksmiths unemployed by cars or TV repairmen unemployed by printed circuits never got another job, unemployment would not be 5 percent, or 10 percent in a bad year. It would be 50 percent and climbing.

Each month in the United States — a place with about 160 million civilian jobs — 1.7 million of them vanish. Every 30 days, in a perfectly normal manifestation of creative destruction, over 1 percent of the jobs go the way of the parlor maids of 1910. Not because people quit. The positions are no longer available. The companies go out of business, or get merged or downsized, or just decide the extra salesperson on the floor of the big-box store isn’t worth the costs of employment.

What you hear on the evening news is the monthly net increase or decrease in jobs, with some 200,000 added in a good month. But the gross figure of 1 percent of jobs lost per month is the relevant one for worries about technological unemployment. It’s well over 10 percent per year at simple interest. In just a few years at such rates — if disemployment were truly permanent — a third of the labor force would be standing on street corners, and the fraction still would be rising. In 2000, well over 100,000 people were employed by video stores, yet our street corners are not filled with former video store clerks asking for loose change.

We could “save people’s jobs” by stopping all innovation. You would do next year exactly what you did this year. Capital as well as labor would perpetually be employed the same way. But then we would perpetually have the same income. That’s nice if you’re doing well now. It’s not so nice if you’re poor or young.

Job protections for the old have in fact already created a dangerous class of unemployed youths in the world — 50 percent among Greeks and black South Africans, for instance.

June 15, 2017

Words & Numbers: What You Should Know About Poverty in America

Published on 14 Jun 2017

Poverty is a big deal – it affects about 41 million people in the United States every year – yet the federal government spends a huge amount of money to end poverty. So much of the government’s welfare spending gets eaten up by bureaucracy, conflicting programs, and politicians presuming they know how people should spend their own money. Obviously, this isn’t working.

This week on Words and Numbers, Antony Davies and James R. Harrigan delve into how people can really become less poor and what that means for society and the government.

May 30, 2017

QotD: The uses of IQ

Suppose that the question at issue regards individuals: “Given two 11 year olds, one with an IQ of 110 and one with an IQ of 90, what can you tell us about the differences between those two children?” The answer must be phrased very tentatively. On many important topics, the answer must be, “We can tell you nothing with any confidence.” It is well worth a guidance counselor’s time to know what these individual scores are, but only in combination with a variety of other information about the child’s personality, talents, and background. The individual’s IQ score all by itself is a useful tool but a limited one.

Suppose instead that the question at issue is: “Given two sixth-grade classes, one for which the average IQ is 110 and the other for which it is 90, what can you tell us about the difference between those two classes and their average prospects for the future?” Now there is a great deal to be said, and it can be said with considerable confidence — not about any one person in either class but about average outcomes that are important to the school, educational policy in general, and society writ large. The data accumulated under the classical tradition are extremely rich in this regard, as will become evident in subsequent chapters.

[…]

We agree emphatically with Howard Gardner, however, that the concept of intelligence has taken on a much higher place in the pantheon of human virtues than it deserves. One of the most insidious but also widespread errors regarding IQ, especially among people who have high IQs, is the assumption that another person’s intelligence can be inferred from casual interactions. Many people conclude that if they see someone who is sensitive, humorous, and talks fluently, the person must surely have an above-average IQ.

This identification of IQ with attractive human qualities in general is unfortunate and wrong. Statistically, there is often a modest correlation with such qualities. But modest correlations are of little use in sizing up other individuals one by one. For example, a person can have a terrific sense of humor without giving you a clue about where he is within thirty points on the IQ scale. Or a plumber with a measured IQ of 100 — only an average IQ — can know a great deal about the functioning of plumbing systems. He may be able to diagnose problems, discuss them articulately, make shrewd decisions about how to fix them, and, while he is working, make some pithy remarks about the president’s recent speech.

At the same time, high intelligence has earmarks that correspond to a first approximation to the commonly understood meaning of smart. In our experience, people do not use smart to mean (necessarily) that a person is prudent or knowledgeable but rather to refer to qualities of mental quickness and complexity that do in fact show up in high test scores. To return to our examples: Many witty people do not have unusually high test scores, but someone who regularly tosses off impromptu complex puns probably does (which does not necessarily mean that such puns are very funny, we hasten to add). If the plumber runs into a problem he has never seen before and diagnoses its source through inferences from what he does know, he probably has an IQ of more than 100 after all. In this, language tends to reflect real differences: In everyday language, people who are called very smart tend to have high IQs.

All of this is another way of making a point so important that we will italicize it now and repeat elsewhere: Measures of intelligence have reliable statistical relationships with important social phenomena, but they are a limited tool for deciding what to make of any given individual. Repeat it we must, for one of the problems of writing about intelligence is how to remind readers often enough how little an IQ score tells about whether the human being next to you is someone whom you will admire or cherish. This thing we know as IQ is important but not a synonym for human excellence.

Charles Murray, “The Bell Curve Explained”, American Enterprise Institute, 2017-05-20.

May 18, 2017

You Can’t Trust Employment Statistics

Published on 17 May 2017

There is no truly good way to measure unemployment, which makes it pretty easy for successive administrations to claim that unemployment is consistently improving. But when we do our level best to include all of the unemployed in the numbers, what we learn is that unemployment levels now are higher than they were at the beginning of the Great Recession. That’s the bad news. The good news is that things actually have been getting better over time. In this week’s episode, James and Antony take a look at the actual unemployment numbers to get to the bottom of what they really mean.

Get the facts here:

https://fee.org/articles/you-cant-trust-unemployment-statistics/

May 11, 2017

Words & Numbers: The Minimum Wage Conspiracy

Published on 10 May 2017

This week, James & Antony tackle minimum wage laws and present some hard facts that might surprise a lot of people.

See the YouTube description for a long list of links related to this discussion.

May 7, 2017

Deadly Africa

Kim du Toit reposted something he wrote back in 2002 about the dangers to life and limb people face in Africa before you factor in dysfunctional governments, terrorists, and continuing ethnic disputes from hundreds of years ago:

When it comes to any analysis of the problems facing Africa, Western society, and particularly people from the United States, encounter a logical disconnect that makes clear analysis impossible. That disconnect is the way life is regarded in the West (it’s precious, must be protected at all costs etc.), compared to the way life, and death, are regarded in Africa. Let me try to quantify this statement.

In Africa, life is cheap. There are so many ways to die in Africa that death is far more commonplace than in the West. You can die from so many things: snakebite, insect bite, wild animal attack, disease, starvation, food poisoning… the list goes on and on. At one time, crocodiles accounted for more deaths in sub-Saharan Africa than gunfire, for example. Now add the usual human tragedy (murder, assault, warfare and the rest), and you can begin to understand why the life expectancy for an African is low — in fact, horrifyingly low, if you remove White Africans from the statistics (they tend to be more urbanized, and more Western in behavior and outlook). Finally, if you add the horrifying spread of AIDS into the equation, anyone born in sub-Saharan Africa this century will be lucky to reach age forty.

I lived in Africa for over thirty years. Growing up there, I was infused with several African traits — traits which are not common in Western civilization. The almost-casual attitude towards death was one. (Another is a morbid fear of snakes.)

So because of my African background, I am seldom moved at the sight of death, unless it’s accidental, or it affects someone close to me. (Death which strikes at total strangers, of course, is mostly ignored.) Of my circle of about eighteen or so friends with whom I grew up, and whom I would consider “close”, only about eight survive today — and not one of the survivors is over the age of fifty. Two friends died from stepping on landmines while on Army duty in Namibia. Three died in horrific car accidents (and lest one thinks that this is not confined to Africa, one was caused by a kudu flying through a windshield and impaling the guy through the chest with its hoof — not your everyday traffic accident in, say, Florida). One was bitten by a snake, and died from heart failure. Another two also died of heart failure, but they were hopeless drunkards. Two were shot by muggers. The last went out on his surfboard one day and was never seen again (did I mention that sharks are plentiful off the African coasts and in the major rivers?). My experience is not uncommon in South Africa — and north of the Limpopo River (the border with Zimbabwe), I suspect that others would show worse statistics.

The death toll wasn’t just confined to my friends. When I was still living in Johannesburg, the newspaper carried daily stories of people mauled by lions, or attacked by rival tribesmen, or dying from some unspeakable disease (and this was pre-AIDS Africa too) and in general, succumbing to some of Africa’s many answers to the population explosion. Add to that the normal death toll from rampant crime, illness, poverty, flood, famine, traffic, and the police, and you’ll begin to get the idea.

My favorite African story actually happened after I left the country. An American executive took a job over there, and on his very first day, the newspaper headlines read:

“Three Headless Bodies Found”.

The next day: “Three Heads Found”.

The third day: “Heads Don’t Match Bodies”.You can’t make this stuff up.

April 30, 2017

[p-hacking] “is one of the many questionable research practices responsible for the replication crisis in the social sciences”

What happens when someone digs into the statistics of highly influential health studies and discovers oddities? We’re in the process of finding out in the case of “rockstar researcher” Brian Wansink and several of his studies under the statistical microscope:

Things began to go bad late last year when Wansink posted some advice for grad students on his blog. The post, which has subsequently been removed (although a cached copy is available), described a grad student who, on Wansink’s instruction, had delved into a data set to look for interesting results. The data came from a study that had sold people coupons for an all-you-can-eat buffet. One group had paid $4 for the coupon, and the other group had paid $8.

The hypothesis had been that people would eat more if they had paid more, but the study had not found that result. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, publishing null results like these is important — failure to do so leads to publication bias, which can lead to a skewed public record that shows (for example) three successful tests of a hypothesis but not the 18 failed ones. But instead of publishing the null result, Wansink wanted to get something more out of the data.

“When [the grad student] arrived,” Wansink wrote, “I gave her a data set of a self-funded, failed study which had null results… I said, ‘This cost us a lot of time and our own money to collect. There’s got to be something here we can salvage because it’s a cool (rich & unique) data set.’ I had three ideas for potential Plan B, C, & D directions (since Plan A had failed).”

The responses to Wansink’s blog post from other researchers were incredulous, because this kind of data analysis is considered an incredibly bad idea. As this very famous xkcd strip explains, trawling through data, running lots of statistical tests, and looking only for significant results is bound to turn up some false positives. This practice of “p-hacking” — hunting for significant p-values in statistical analyses — is one of the many questionable research practices responsible for the replication crisis in the social sciences.

H/T to Kate at Small Dead Animals for the link.

April 29, 2017

“Don’t count fat; don’t fret over what kind of fat you’re getting, per se. Just go for walks and eat real food”

Earlier this week, Colby Cosh rounded up some recent re-evaluations of “settled food science”:

Their first target was the Sydney Diet Heart Study (1966-73), in which 458 middle-aged coronary patients were split into a control group and an experimental group. The latter group was fed loads of “healthy” safflower oil and safflower margarine in place of saturated fats. Even at the time it was noticed that the margarine-eaters died sooner, although their total cholesterol levels went down: the investigators sort of shrugged and wrote that heart patients “are not a good choice for testing the lipid hypothesis.” Their data, looked at now, shows that the increased mortality in the margarine group was attributable specifically to heart problems.

The team’s reanalysis of the Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73) is more hair-raising. This study involved nearly 10,000 Minnesotans at old-age homes and mental hospitals. The investigators had near-complete control of the subjects’ diets, and were able to autopsy the ones who died. But much of their data, including the autopsy results, ended up misplaced or ignored. Some of it disappeared into a master’s thesis by a young statistician, now a retired older chap, who helped with the 2016 paper and is named at its head as one of the authors.

In the Minnesota study, replacement of saturated fats with corn oil led, again, to reductions in total cholesterol. This finding was touted at major conferences, and it became one of the key moments in the creation of the classic diet-heart myth. This time nobody but the guy who wrote the thesis even noticed that the patients in the corn oil group were, overall, dying a little faster. The 2016 re-analysis uncovered a dose-response relationship: the more the patients’ total cholesterol decreased, the faster they died.

The Sydney and Minnesota studies themselves may have caused a few premature deaths, which is a possibility we accept as the price of science. But the limitations and omissions of the researchers, and the premature commitment of doctors to a total-cholesterol model, helped create a suspicion of saturated fats. This flooded into frontline medical advice and the wider culture, and it put margarine on millions of tables, pushed consumers toward deadly trans fats, and put millions of people with innately high cholesterol levels through useless diet austerity. The scale of the error is numbing, unfathomable.