Published on 4 Apr 2016

The Netherlands were surrounded by World War 1 from 1914 onwards and their stance of armed neutrality made it difficult to manoeuvre between the Entente and the Central Powers. And while the Netherlands never joined the conflict in the end, the war took its toll on the nation.

April 5, 2016

Armed Neutrality – The Netherlands In WW1 I THE GREAT WAR Special

March 29, 2016

Audacity & Gold Bars – The First Voyage Of SMS Möve I THE GREAT WAR Special

Published on 28 Mar 2016

The German raider SMS Möve and her captain Nikolaus Graf zu Dohna-Schlodien were already legendary during World War 1. Their exploits sound like pirate tales of the Golden Age of Piracy: Ever eluding the Allied fleet, the Möve brought down over 30 ships, captured multiple hundred crewmen and brought home over 100.000 Mark in gold bars when they returned the first time.

February 13, 2016

You notice you only ever hear of the Baltic Dry Index when it’s way down?

Tim Worstall says that the Baltic Dry Index is way down … and there’s zero reason to panic over it:

The Baltic Dry Index is now down to 293, near 50% down on a year ago and almost 40% down just so far this year. This does not though, despite a remarkable amount of panicking over it, mean that global trade has fallen off a cliff. It does not even mean that global trade has contracted at all. The important point here being, as it is about any other price in the economy, that the price is determined by the interplay of supply and demand, not just demand alone.

Actually, we need to take a further step back. The Baltic Dry Index is an index of the price of shipping (specifically, of large bulk dry cargoes like grain and iron ore, there are other similar measures for oil, containers and so on), not an indication of the volume of shipping or trade. It’s then that we have to recall that prices are about the interplay of supply and demand, not just demand itself.

And the truth is that global trade is not shrinking, despite what is happening to the price of doing that shipping of that trade. Now, if trade were shrinking that would be a problem, yes, because it would be an indication of a general slow down, possibly even recession, in the global economy. That’s not something we want to happen. But the price of shipping falling is something very different.

[…]

Yes, the Baltic Dry Index has collapsed: but that’s a collapse in the price of shipping, not in the volume of shipping nor of global trade. Far from this being a bad sign for the global economy, it contains within it the seeds of good news. If shipping is becoming cheaper therefore it will be cheaper to trade and there will be more of it. Which is good news, because more trade makes us all richer.

And we need to recall this basic point when we think about either economics or public policy. Yes, price changes are indeed telling us something about the economy around us. But we do have to be careful that we pick up the right message. A falling price can be a symptom of increased supply just as much as it can be of reduced demand.

February 5, 2016

“I’m all for a Darwinian Search and Rescue Plan, if you follow me”

Duffelblog reports on the kind of boaters the US Coast Guard has to rescue:

Nearly 83 percent of mariner rescues since 1960 involved unrelentingly stupid behaviors and/or people, according to a recent study by the U.S. Coast Guard.

Though the service treats all search and rescue situations equally, most on-scene commanders will privately admit that a majority of the time “it was just some dumb bastard with no concern for personal safety,” according to the study’s authors.

“These statistics are unthinkable,” said Coast Guard spokesperson Lt. Carla Willmington. “Our service prides itself on response time, SAR organization, and comprehensive rescue pattern analysis. But it’s tough to stay on task when the bulk of these cases involve people paralyzed from the neck up. ”

The U. S. Coast Guard Office of Search and Rescue report examined nearly all cases handled on inland and offshore waters from 1960 through 2014. Following the Federal Boating Act of 1971, increases in cases by “fucking idiots” and “goddamn morons” have been staggering, and very challenging to the service as it struggles to operate under a minimal budget.

Between 2010 and 2014, the most recent years studied, incidents involving “total assholery” increased from 10,687 to 38,335.

January 23, 2016

World of Warships – How To Not Suck

Published on 20 Jun 2015

If I said to you “What’s Port?” and your answer is “A fortified wine from Portugal served by the Wardroom Steward at Mess Dinners” you’re either a Royal Naval Officer or someone who could probably benefit from watching this video. There’s no cure for being a Royal Naval Officer, but the cure for sucking at World of Warships is just one click away.

December 27, 2015

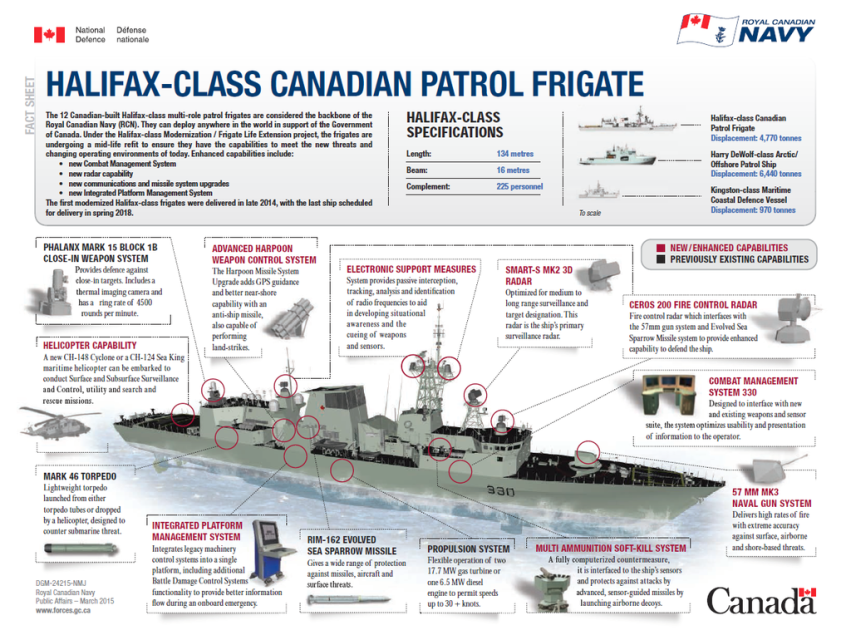

The refit and modernization program for the RCN’s Halifax class frigates

In the Chronicle Herald, Andrea Gunn reports on the Royal Canadian Navy’s refit program for the twelve ships in the HMCS Halifax class, being done in Victoria and Halifax:

A $4.3-billion, decade-long life extension and modernization of Canada’s Halifax-class frigates has now been completed on more than half the fleet.

Work started in 2010 on the mid-life refit and modernization process, which has been concluded on HMCS Halifax, Fredericton, Montreal and Charlottetown at the Irving-owned Halifax Shipyard, and on HMCS Calgary, Winnipeg and Vancouver at Seaspan in Victoria.

The other five vessels, HMCS St. John’s, Ottawa, Ville de Quebec and Toronto, have all entered refit and are at various stages of completion and testing. All major work for the program, which is on schedule and on budget, is set to be finished by 2019.

The project’s aim is to extend the lifespan of the fleet to sustain Canada’s naval operations during the design and construction phase of the new fleet of Canadian surface combatants, set to be delivered by 2033. The Halifax-class frigates have been in operation since 1992, and planning and preparation for the modernization project began in 2002.

Royal Canadian Navy Commodore Craig Baines, commander of the Atlantic fleet, recently returned from two months of major multinational exercises that utilized three of the modernized vessels. HMCS Halifax, Montreal and Winnipeg participated in Joint Warrior, and Winnipeg and Halifax participated in Trident Juncture, the largest NATO military exercise since the Cold War.

“From where we were previously to where we are now, it’s like you have a brand new ship,” Baines told The Chronicle Herald.

The modernized vessels are equipped with a new radar suite and have had major upgrades to the communications and warfare systems. But it’s the $2-billion upgrade to the fleet’s combat management systems — a completely redesigned command and control centre with plenty of new features — that is largely responsible for that new ship feel.

Click image to see full-sized. H/T to @RUSI_NS for the link.

December 2, 2015

Can the Royal Navy fund a “cheap and cheerful” frigate?

In the most recent British government SDSR plan, the Royal Navy’s hopes to get 13 new Type 26 frigates have been trimmed down to only eight. Save the Royal Navy speculates on developing a cheaper ship design that could perhaps fill the gap:

Is it really possible to produce a fully effective frigate that is significantly cheaper than a T26? Let us call it the ‘Type 31’, It still requires point defence missiles, anti-ship weaponry, a hangar and small flight deck (even if only for a UAV or Lynx size helicopter), plus a command and control system and suite of sensors. Although the hull size could be reduced, a simpler propulsion system used and the anti-submarine capability eliminated or reduced. You might cut the cost by 30%, and get a general purpose ship but there is still the cost of developing a new design. (At least £200M has already been spent on the T26 design as well as various development ‘blind alleys’ along the way.) A second frigate type will also need its own equipment support logistics and training pipelines.

The desire to create an exportable frigate is laudable but will we not be re-inventing the wheel when there are already cheaper foreign designs that could be licensed or adapted. The highly successful German MEKO design and the Danish Stanflex system are good examples.

If your warship is designed to cope in high-intensity conflict then it will need expensive weapons and sensors. Today’s generation of supersonic anti-ship missiles are truly formidable. Modern surface ships face greater and more diverse threats than ever. To counter this requires good sensors, agile missiles and an array of decoys, backed up by last-ditch close in weapon systems (CIWS). Although the general purpose frigate may not be dedicated to hunting submarines, it will still need a decent sonar to give some hope of prosecuting a submarine or detecting and avoiding torpedo attack. Submarines are also getting more and more stealthy with a growing arsenal of weapons. Without quiet propulsion and sophisticated sonars (i.e. towed arrays) that can detect threats at range and helicopters to attack, the Type 31 could ‘just be another target’.

If your escorts are really going to escort anything eg. an aircraft carrier or merchant shipping, then it needs more than just last-ditch self-defence weapons. A Phalanx CIWS may defend the ship it is mounted on, but it is little use protecting another vessel. If the escort ship can only defend itself, it has very limited use or must be permanently on the offensive. The Sea Ceptor being fitted to the Type 23 and Type 26 frigates has the major advantage over the Sea Wolf it replaces by having more than double the range (around 25Km), significantly extending the size of the protection umbrella over ships being escorted. Frigates are traditionally built to hunt submarines, if our Type 31 has no real ASW capability then it is pretty limited in a wartime role.

Sleek, fast and loved by their crews, the Type 21 was the poster child for the cheap frigate. There is a very fine line between a successful ‘less capable, cheaper frigate’ and a compromised warship design that becomes a liability. The Type 21 Frigate design of the 1970s was designed by a private company and accepted by the RN as a way to get a modern and affordable frigate to sea. Unfortunately when tested in the heat of the Falklands war their deficiencies became obvious. A top-heavy design on a lightweight hull, they suffered structural problems in the prolonged South Atlantic operations. They were also inadequately armed and suffered accordingly. God help them if they had gone up against Soviet aircraft or missiles. Ironically the surviving Type 21s still soldier on today in the Pakistani navy. Upgraded with a Phalanx system and Chinese SAMs / Harpoon missiles they are now slightly more potent.

November 6, 2015

The evolution of the Royal Navy’s ship designs

This post is a nice summary of the Royal Navy’s frigates, destroyers, and cruisers from the Second World War through to the present day:

Before the Second World War the RN was predominantly a “cruiser navy”, holding down a range of global deployments with its 15 heavy and 41 light cruisers. These ships had endurance and combat power at the core of their designs, each could operate alone for extended periods, effectively defend itself in most circumstances and demonstrate the interest or resolve of the government in a particular region. The ensuing World War and the Cold War radically changed the type of warships the RN needed. Instead of cruisers built for endurance and complex warfighting the navy built a profusion of smaller frigates and destroyers, mainly to guard convoys and fight submarines close to the UK and in the North Atlantic. To carry out these tasks the navy could make do with smaller, cheaper, ships with relatively shorter legs and far less ability to act independently in high threat environments. Trade-offs like these were made in order to ensure the navy got enough escorts to protect the convoys which would be vital to Britain’s survival in the event of a war; and to hunt the Soviet ballistic missile submarines that threatened NATO. These were ships designed to act as part of a military system that would defeat the threat posed by hostile submarines. This system also included land based aircraft, anti submarine helicopters, aircraft and helicopter carriers and the enormous US/NATO SOSUS fixed sonar array. The Leander class is probably the most famous example of these sort of light frigates, operated by the RN into the early 1990s. When the immediate and pressing threat from submarines operating in the North Atlantic, be they German or Soviet, ceased to exist so the naval forces the UK had constructed to defeat them also fell by the wayside. These ships were, broadly speaking, a product of their time and a deviation from the much older structure that had served the RN well for centuries. This structure consisted of a core “battle fleet”, made up of capital ships; mainly there to act as a deterrent, supported by powerful forward deployed cruisers that conducted most of the day to day activity.

By modern standards almost all of the cheap and numerous frigates and destroyers of the past, even the excellent Leanders, would be classed as lightly armed corvettes. The simple fact was that these cheap and numerous ships sacrificed a lot of capability in order to achieve the affordability necessary to build them in numbers. They were still recognisable as frigates built in the convoy escort mold. Similarly the Type 42 anti-aircraft warfare destroyers, in service from the mid-1970s, were also a design that compromised range and armament for numbers. At only 3500 tonnes the Batch 1 Type 42s were clearly a very light and economical design. When compared with their American counterparts, the 8000 tonne Spruance class, it’s clear that these ships sacrificed range and armament for economy and numbers. Both the Leanders and the Type 42s are recognisable as frigates and destroyers, light warships designed to act in groups and alongside other warships, auxiliaries and aircraft to be effective in combat. The closest the RN came to “cruiser” designs during the Cold War were the eight County Class missile destroyers commissioned in the early 1960s and HMS Bristol, the sole survivor of the pre-1968 carrier escort programme. While these destroyer classes were cruiser-like in some aspects, they carried a far more comprehensive armament and had a greater range (in terms of fuel) than their contemporaries, they lacked the self-sustainment ability, protection, survivability and range of “true” cruisers. While Bristol was initially labelled a light cruiser by Jane’s, the Royal Navy always saw her for what she was: an oversize missile destroyer with the similar limitations to the navy’s other destroyers.

With the later Type 22 and 23 frigates the RN moved to fewer, more individually capable, platforms. This change was partly necessitated by the introduction of a new generation of bigger towed array sonars which required larger ships to operate effectively. Despite their greatly improved self defence ability, achieved by fitting the Sea Wolf point defence missile system, these ships were still designed to be expendable escorts and lacked the endurance of cruisers. That said, these two classes signalled the start of the navy’s shift from a fleet of numerous, small and cheap escorts to fewer, larger ships capable of independent operations in a high threat environment.

October 3, 2015

Great Britons: Isambard Kingdom Brunel Hosted by Jeremy Clarkson – BBC Documentary

Published on 16 Jul 2014

Jeremy Clarkson follows in the footsteps of the great engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel whose designs for bridges, railways, steamships, docks and buildings revolutionised modern engineering. But his boldness and determination to succeed often led him to repeatedly risk his own life. Jeremy Clarkson, discovers for himself just how terrifying that was.

H/T to Ghost of a Flea for the link.

September 22, 2015

Submarines, Dreadnoughts and Battle Cruisers – The Navies of World War 1 I THE GREAT WAR – Special

Published on 21 Sep 2015

Even though there was only one major naval battle in the Atlantic during World War 1, the navies played a huge role during the entire conflict. From troop transports to supplies and from unrestricted submarine warfare to the landing at Gallipoli: The life of a sailor in the Great War was dangerous. And it wasn’t just the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea was full of navies and battle ships. Especially fairly new ship types like the submarine or the Dreadnought were a force to be reckoned with.

August 22, 2015

Division of Labor: Burgers and Ships (Everyday Economics 2/7)

Published on 24 Jun 2014

A simple example of hamburgers being made at home versus at a restaurant can help illuminate the explosion of prosperity since the Industrial Revolution. The story of the division of labor and development of specialized tools is not a new one — Adam Smith began The Wealth of Nations with this concept. Yet it still has tremendous explanatory power about the world we inhabit.

August 21, 2015

Escalation At Sea and Russia Up Against the Wall I THE GREAT WAR – Week 56

Published on 20 Aug 2015

The Entente was in desperate need of American supplies and so the German submarine campaign in the Atlantic was a real problem. The British started to run false flag operations with so called Q-Ships to hunt down U-Boats which lead to the so called Baralong Incident this week. In the meantime, Russia was standing up against the wall as the fortresses of Kovno and Novogeorgievsk were falling to the Germans leading to a catastrophic loss in men, equipment and supplies.

August 5, 2015

The state of the Royal Canadian Navy

It’s worse than you might think:

HMCS Athabaskan

This October, NATO is launching Trident Juncture, its largest and most ambitious military exercise in a decade. The massive land, sea and air exercise will be held in the Mediterranean and will include 36,000 troops from 30 nations. Its goal will be to help the fictitious country of Sorotan, “a non-NATO member torn by internal strife and facing an armed threat from an opportunistic neighbour.” Not surprisingly, this is widely seen as an explicit response to Moscow’s increasingly belligerent pressure on the alliances’ eastern borders. The Canadian government, an outspoken critic of Russian President Vladimir Putin and the invasion of Ukraine, had planned to send its flagship destroyer, HMCS Athabaskan, as “a strong signal to the Russians,” whose ships and aircraft have also been bumping up against Canada’s territorial claims in the Arctic.

But, last week, it was reported by the Ottawa Citizen that the 43-year-old Athabaskan was no longer seaworthy and is being sent back to Halifax for extensive repairs. Athabaskan is a fitting symbol of the overall state of the Navy: Its engines require an overhaul, the hull is cracked, the decks need replacing, and the weapon systems are questionable. Even Rear Admiral John Newton, commander of Maritime Forces Atlantic, describes his flagship as worn and tired.

In February, during a storm off the East Coast, Athabaskan was damaged and a number of engines failed. After that, the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) decided it was no longer capable of weathering the heavy seas of the North Atlantic, so it was sent south for calmer seas. Nonetheless, its engines broke down in Florida, then again in placid Caribbean waters.

“It was garbage. Everything was always breaking,” says Jason Brown, who served as an electrician and technician on Athabaskan for seven years, ending in 2010. “We did 150 to 300 corrective maintenances a month.” Although Brown praises the ship’s crew, he often spent 20-hour days trying to fix equipment. “The two main engines didn’t like to play nice together. It was 4½ years before that issue got fixed.”

[…]

Compared to its allies, the Canadian Navy is now only one-third the size it should be, given our GDP, and can only play smaller and smaller roles. Stanley Weeks of the U.S. Naval War College, a former U.S. admiral who follows NATO closely, is dismayed at the decline of the RCN. “[Canadian politicians] need more seriousness. Canada is an inherently maritime nation, dependent on overseas markets, especially in Asia Pacific, and, therefore, it has to be a contributing stakeholder, militarily and diplomatically.” He believes American military leaders in the Pentagon have not yet grasped the serious implications of losing the Canadian destroyers. Regardless, “Canadians should worry more about this than Washington.”

June 6, 2015

QotD: Getting ashore on D-Day

At 04.30 hours on the Prince Baudouin, the waiting soldiers heard the call: “Rangers, man your boats!” On other landing ships there was a good deal of chaos getting the men into the landing craft. Some infantrymen were so scared of the sea that they had inflated their life jackets on board ship and then could not get through the hatches. As they lined up on deck, an officer in the 1st Division noticed that one man was not wearing his steel helmet. “Get your damn helmet on,” he told him. But the soldier had won so much in a high card game that his helmet was a third full. He had no choice. “The hell with it,” he said, and emptied it like a bucket on the deck. Coins rolled all over the place. Many soldiers had their field dressings taped to their helmet; others attached a pack of cigarettes wrapped in cellophane.

Those with heavy equipment, such as radios and flame-throwers which weighed 100 pounds, had great difficulty descending the scramble nets into the landing craft. It was a dangerous process in any case, with the small craft rising and falling and bouncing against the side of the ship. Several men broke ankles or legs when they mistimed their jump or were caught between the rail and the ship’s side. It was easier for those lowered in landing craft from davits, but a battalion headquarters group of the 29th Infantry Division experienced an inauspicious start a little later when their assault craft was lowered from the British ship Empire Javelin. The davits jammed, leaving them for thirty minutes right under the ship’s heads. “During this half-hour,” Major Dallas recorded, “the bowels of the ship’s company made the most of an opportunity which Englishmen have sought since 1776.” Nobody inside the ship could hear their yells of protest. “We cursed, we cried and we laughed, but it kept coming. When we started for shore, we were all covered with shit.”

Anthony Beevor, D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, 2009.

June 4, 2015

Installing the forward island on HMS Prince of Wales

The second of the Queen Elizabeth class of aircraft carriers for the Royal Navy is still under construction. Here’s a time-lapse video of the transportation and installation of the forward island:

Published on 26 May 2015

Timelapse video charting the incredible journey of the 680-tonne command centre of the Royal Navy’s latest aircraft carrier – HMS Prince of Wales – as it left its construction hall in Govan, Glasgow this month before being installed on the under-construction carrier in Rosyth dockyard, near Edinburgh.