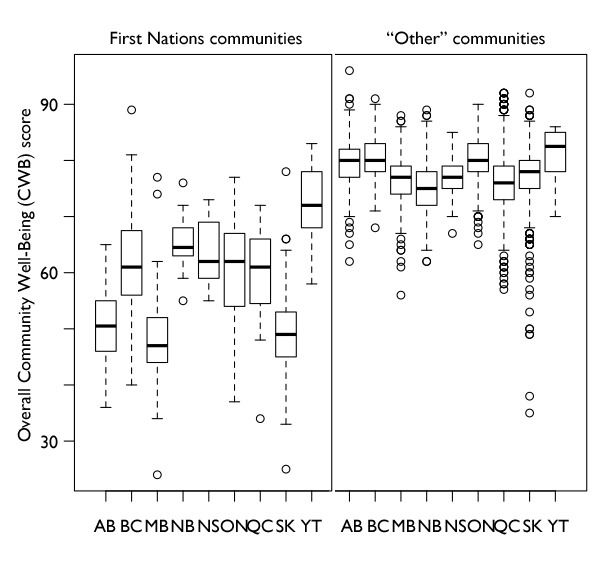

Over the weekend, Colby Cosh posted this depressing box-and-whisker plot (aka “boxplot”) from statistical data on First Nations communities:

Why did I want to look at this information this way? Because Canada actually performed an inadvertent natural experiment with residential schools: in New Brunswick (and in Prince Edward Island) they did not exist. If the schools had major negative effects on social welfare flowing forward into the future we now inhabit, New Brunswick’s Indians would be expected to do better than those in other provinces. And that does turn out to be the case. You can see that the top three-quarters of New Brunswick Indian communities would all be above the median even in neighbouring Nova Scotia, whose FN communities might otherwise be expected to be quite comparable. (Remember that each community, however large, is just one point in these data. Toronto’s one point, with an index value of 84. So is Kasabonika Lake, estimated 2006 population 680, index value 47.)

On the other hand, and this is exactly the kind of thing boxplots are meant to help one notice, the big between-provinces difference between First Nations communities isn’t the difference between New Brunswick and everybody else. It’s the difference between the Prairie Provinces and everybody else including New Brunswick — to such a degree, in fact, that Canada probably should not be conceptually broken down into “settler” and “aboriginal” tiers, but into three tiers, with prairie Indians enjoying a distinct species of misery. (This shows up in other, less obvious ways in the boxplot diagram. You notice how many lower-side outliers there are in Saskatchewan? That dangling trail of dots turns out to consist of Indian and Métis towns in the province’s north — communities that are significantly or even mostly aboriginal, but that aren’t coded as “FN” in the dataset.)

I fear that the First Nations data for Alberta are of particular note here: on the right half of the diagram we can see that Alberta’s resource wealth (in 2006, remember) helped nudge the province ahead of Saskatchewan and Manitoba in overall social-development measures, but it doesn’t seem to have paid off very well for Indians. This isn’t a surprising outcome, mind you, if you live in Alberta; we have rich Indian bands and plenty of highly visible band-owned businesses, but the universities are not yet full of high-achieving members of those bands, and the downtown shelters in Edmonton, sad to say, still are.