Drachinifel

Published 27 Jan 2021A brief history of the Royal Canadian Navy from its origins to the end of WW2.

Sources:

https://archive.org/details/seaisatourgatesh00germ

https://www.canada.ca/en/navy/services/history/naval-service-1910-2010.html

Legion Magazine – “Over The Side: The Courageous Boarding Of U-94”

www.amazon.co.uk/No-Higher-Purpose-Operational-1939-1943/dp/1551250616

www.amazon.co.uk/Canadas-Navy-Century-General-Interest/dp/0802042813/Free naval photos and more – www.drachinifel.co.uk

Want to support the channel? – https://www.patreon.com/Drachinifel

Want a shirt/mug/hoodie – https://shop.spreadshirt.com/drachini…

Want a poster? – https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/Drachinifel

Want to talk about ships? https://discord.gg/TYu88mt

Want to get some books? www.amazon.co.uk/shop/drachinifelDrydock

Episodes in podcast format – https://soundcloud.com/user-21912004

May 6, 2021

The Royal Canadian Navy – Sinking you, but politely

April 11, 2021

HMCS Warrior (R31) – Colossus-class Light Aircraft Carrier

canmildoc

Published 30 Mar 2013HMS Warrior (R31) was a Colossus-class light aircraft carrier which served in the Royal Canadian Navy from 1946 to 1948 (as HMCS Warrior). She was transferred to the Royal Canadian Navy, commissioned as HMCS Warrior and placed under the command of Captain Frank Houghton. She entered Halifax harbour on 31 March 1946, a week after leaving Portsmouth. She was escorted by the destroyer HMCS Micmac and the minesweeper HMCS Middlesex. The RCN experienced problems with the unheated equipment during operations in cold North Atlantic waters off eastern Canada during 1947. The RCN deemed her unfit for service and, rather than retrofit her with equipment heaters, made arrangements with the Royal Navy to trade her for a more suitable aircraft carrier of the Majestic class which became HMCS Magnificent (CVL 21) on commissioning. [Original text from Wikipedia]

Tags: Colossus Class Light Aircraft Carrier, HMCS Warrior, HMCS, RCN, Royal Canadian Navy, aircraft carrier, CV, Halifax

From the Wikipedia description of HMCS Warrior:

Warrior was a Colossus-class light aircraft carrier that was 630 feet 0 inches (192.0 m) long between perpendiculars and 695 feet 0 inches (211.8 m) overall with a beam at the waterline of 80 feet 0 inches (24.4 m) and an overall width of 112 feet 6 inches (34.3 m). The ship had a mean draught of 23 feet 3 inches (7.1 m). Warrior had a standard displacement of 13,350 long tons (13,560 t) when built and a full load displacement of 18,300 long tons (18,600 t). The aircraft carrier had a flight deck 690 feet 0 inches (210.3 m) long that was 80 feet 0 inches (24.4 m) wide and was 39 feet 0 inches (11.9 m) above the water. The flight deck tapered to 45 feet (14 m) at the bow. For takeoffs, the flight deck was equipped with one BH 3 aircraft catapult capable of launching 16,000-pound (7,257 kg) aircraft at 66 knots (122 km/h). For landings, the ship was fitted with 10 arrestor wires capable of stopping a 15,000-pound (6,804 kg) aircraft, with two safety barriers rated at stopping a 15,000-pound aircraft at 40 knots (74 km/h). Warrior had two aircraft elevators located along the centreline of the ship that were 45 by 34 feet (13.7 by 10.4 m) and could handle aircraft up to 15,000 pounds on a 36-second cycle. The aircraft hangar was 275 by 52 feet (83.8 by 15.8 m) with a further 57 by 52 feet (17.4 by 15.8 m) section beyond the aft elevator, all with a clearance of 17 feet 6 inches (5.3 m). The hangar was divided into four sections by asbestos fire curtains. The hangar was fully enclosed and could only be entered by air locks and the lifts, due to the hazardous nature of aviation fuel and oil vapours. The vessel had stowage for 98,600 Imperial gallons (448,244 l; 118,414 US gal) of aviation fuel.

The ship was powered by steam created by four Admiralty 3-drum type boilers driving two Parsons geared turbines, each turning one shaft. The machinery was split into two spaces, each containing two boilers and one turbine, separated by 24-foot (7.3 m) spaces containing aviation fuel. The spaces were situated en echelon within the ship to prevent a single disabling torpedo strike. The engines were rated at 42,000 shaft horsepower (31,319 kW) and the vessel had a capacity for 3,196 long tons (3,247 t) of fuel oil, with an range of 8,300 nautical miles (15,372 km) at 20 knots (37 km/h). The ship’s maximum speed was 25 knots (46 km/h). There was no armour aboard the vessel save for mantlets around the torpedo storage area. There were no longitudinal bulkheads, but the transverse bulkheads were designed to allow the ship to survive two complete sections of the ship being flooded.

Warrior was designed to handle up to 42 aircraft. The aircraft carrier carried a wide range of ordnance for their aircraft from torpedoes, depth charges, bombs, 20 mm cannon ammunition and flares. For anti-aircraft defence, the aircraft carrier was initially armed with four twin-mounted and twenty single-mounted 40 mm Bofors guns. The original radar installation included the Type 79 and Type 281 long-range air search radars, the Type 293 and Type 277 fighter direction radar and the “YE” aircraft homing beacon. The ship had a maximum ship’s company of 1,300, which was reduced in peacetime.

After service with the RCN, Warrior was returned to the Royal Navy, and subsequently sold to Argentina, entering service as ARA Independencia until 1971 when she was struck from the Argentinian navy list and scrapped.

March 17, 2021

Rebuilding the Royal Canadian Navy

I somehow missed this article by Sir Humphrey when he posted it a few weeks back. He’s looking at the Australian and Canadian governments’ respective decisions to use the British Type 26 design to replace their current anti-submarine fleets and considering some of the economic and military concerns that led to the decision.

In both cases there have been media articles in the last week over the programmes and concerns. In Canada, the challenge has been that the cost has grown to a total of $77bn for 15 escorts. There has been cost growth from an originally scheduled $14bn many years ago, and the first of class will not now be delivered until 2031. This has led to suggestions in some media quarters that Canada could do things faster and more cheaply if it simply bought an off the shelf foreign design now and got on with things.

An artist’s rendition of BAE’s Type 26 Global Combat Ship, which was selected as the Canadian Surface Combatant design in 2019, the most recent “largest single expenditure in Canadian government history” (as all major weapon systems purchases tend to be).

(BAE Systems, via Flickr)[…]

The issue now is that Canada will need to establish, almost from scratch, a frigate construction programme and workforce for a finite period of time without a clear plan of what follows on when the last hull is completed. At the same time it will need to run on ships that are becoming increasingly elderly – it is likely that most of the Halifax class will see more than 40 years of service, and some may approach their 50th birthdays before being replaced – something that will pose an increasing maintenance and resource challenge.

Could things be done more cheaply or quickly? Almost certainly yes, but only if you are willing to make massive compromises. It could be possible, for example, to look to licence build an existing design that is already in service. There are plenty of designs out there that could be licence built and brought into service in the next few years — probably at less cost than the T26 programme.

But while this may sound easy, its also a recipe for disaster. It’s easy to look at country X and say “they’re buying this ship for that much” and assume that Canada is getting a bad deal. But Country X is likely to have a very different set of requirements, and their design will reflect it.

For example, Canada needs a ship able to operate with NATO and 5 EYES as a fully integrated player – this adds cost to fit specific systems and equipment that is compatible. Canada will also want to fit bespoke systems to meet national needs – again this will require design changes, that come at a price. Bolting on all manner of different requirements that Canada needs to meet the unique operational circumstances adds price and complexity to the design.

While you probably could take an off the shelf design and build it now, it would be just that, an off the shelf design. It wouldn’t be optimised for local needs, and it wouldn’t have the right equipment, comms, meet local design standards, or be certified for use with national equipment.

You are then faced with two choices – either bring a cheap ship into service that is entirely unsuitable and not designed for your needs, but is a lot cheaper, or spend an enormous amount of money shifting the design to better reflect your needs. If you choose the latter, then suddenly you are adding cost and time in, and the 2031 date will slip even further.

If you choose the former, then you have to accept that the design is “as it comes” and will have minimal Canadian input – so limited industrial offsets, very little economic benefit, and the long-term support solutions will firmly be tied into the country of origin and not Canada. In other words, Canadian taxpayer dollars will be spent to support a foreign economy.

That last point is really the key. Canadian governments, in my lifetime at least, never look at the military requirement as the top priority and sometimes not even the second or third priority. The economic spin-offs, especially in those cases where the benefits can be allocated to marginal parliamentary constituencies, will be the top priority. As is always a talking point in the case of any major military hardware acquisition, this is going to be the “single largest expenditure in Canadian government history”. Just as the replacement of the RCAF’s aged CF-18 fighters will be the largest expenditure in its turn.

March 2, 2021

Warship purchasing is not for the faint-of-heart

Ted Campbell talks about the way the Royal Canadian Navy plans for warship purchases … and how the best-laid plans can be derailed by ignorant political advisors:

An artist’s rendition of BAE’s Type 26 Global Combat Ship, which was selected as the Canadian Surface Combatant design in 2019, the most recent “largest single expenditure in Canadian government history” (until the RCAF gets their replacement for the CF-18 Hornet).

(BAE Systems, via Flickr)

Once upon time,* about 25 to 30 years ago, in the mid 1990s, when I was the director of a small, very specialized team in National Defence Headquarters (NDHQ) in Ottawa, something like this happened: One of my colleague, who had a title like Director of Maritime Requirements or something similar said to one of his principle subordinates, “Look, now that the 280s (Canada had four Tribal Class destroyers with pennant numbers starting at 280, they were often just called ‘280s’) are finished their mid-life refit and now that the new frigates are entering service it is time to put a ‘placeholder’ in the DSP for their eventual replacements.” The DSP was (still is?) the Defence Services Programme, it is the internal document which sets out the long range spending plans (maybe hopes is a better word) for the Canadian Armed Forces.

Anyway, the Navy commander (the officer assigned to write the document, not the Commander of the Royal Canadian Navy who is nicknamed the Kraken (CRCN)) sat at his desk and consulted the most recently approved planning document which, as far as I can remember, called for a surface fleet of 25 combat vessels and four large support ships plus numerous minor war vessels (like minesweepers) and training vessels. The officer then prepared a memorandum for the joint planning staff which said that the Navy would need 25 new combat ships, to be procured between about 2015 and 2035, in five “batches” of five ships each** at a total cost of about $100 Billion, in 2025 dollars. He didn’t say much beyond that, actually, he was just intending to “reserve” some money a generation or so in the future. His memorandum sailed, smoothly, past his boss and the commodore but questions came from a very senior Air Force general: Where he asked, did the $100 Billion come from? That was an outrageous number, he said.

A meeting ensure where the Navy engineering people came and said, “$100 Billion is a very reasonable guesstimate. Our brand new frigate are costing $1 Billion each when they come down the slipway. They will each have cost the taxpayers two to three times that by the time we send them to be broken up thirty or forty years from now. Adding in the inevitable costs of new technology and inflation, which we know is higher for things like military ships and aircraft than it is for consumer goods, then a life-cycle cost of $4 Billion for each ship is very conservative. The admirals and generals huffed and puffed but they didn’t argue ~ they knew that the engineering branch insisted on using life cycle costing, even though no-one but them understood it, and they also knew that arguing with engineers is like mud-wrestling with pigs: everyone gets dirty but the pigs love it.

A decade later, when a new government was planning the National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy, which was all about making the Canadian shipbuilding industry competitive and had very little to do with ships ~ except they would be the “product” for which the Government of Canada would pay top-dollar, the Navy was told it could have fewer ships, in two classes, and someone ~ NOT the military’s engineering branch ~ assigned a cost figure to the project which was, to be charitable, pulled out of some political/public relations staffer’s arse.

[…]

* The story is true, in general, but I was not directly involved in any of it. I learned about what happened from three main sources: 1. routine briefings that my bosses (directors-general and branch chiefs) gave, regularly, to we directors, dealing with what was going on in the HQ and in the big wide world; 2. periodic chats with my colleagues, after work on Friday afternoons, in the bar of the Officers’ Mess ~ many of us regarded 2. as a more reliable source of information than 1.; and 3. in the case of the story about the Navy engineers and the Air Force general, by a friend and colleague who was in the room.

** The idea, long before the National Shipbuilding Strategy, was to keep shipyards moderately busy on a continuous basis. The 25 ships would all be similar: the first “batch” of five would be identical, one to the other; the second “batch” would be very similar but with some improvements; the five ships of batch 3 would be similar to the ships from the second batch and those from batch 4 would be rather like their batch 3 sisters. Finally, the batch 5 ships would be product improved versions of batch 4 ~ they would still be “sisters” of the batch 1 ships, but not, in any way, twins. The idea was that about the time that the batch 5 ships were being delivered the first of the batch 1 ships would be getting ready for a mid-life refit (after 15 to 20 years of service) which would result in it being much more like the batch 5 ships … and so on.

February 15, 2021

HMCS Magnificent (CVL 21) – Majestic-Class Light Aircraft Carrier

canmildoc

Published 7 Apr 2013HMCS Magnificent (CVL 21) was a Majestic-class light aircraft carrier that served the Royal Canadian Navy from 1948-1957.

The third ship of the Majestic class, Magnificent was built by Harland and Wolff, laid down 29 July 1943 and launched 16 November 1944. Purchased from the Royal Navy (RN) to replace HMCS Warrior, she served in a variety of roles, operating both fixed and rotary-wing aircraft. She was generally referred to as the Maggie. Her aircraft complement included Fairey Fireflies and Hawker Sea Furies, as well as Seafires and Avengers.

Tags: HMCS Magnificent, CVL 21, Majestic Class Light Aircraft Carrier, Royal Canadian Navy, RCN, CV, Maggie, Fairey Fireflies, Hawker Sea Furies, Seafires, Avengers, Canada, aircraft carrier, Canada

From the comments:

Tibor80

5 years ago

That’s me with the mike in hand, interviewing the staff. It was the last TV work I did in Canada before leaving the industry and settling on Madison Avenue in the fall of 1954. Don Harron had been hosting a series titled ON THE SPOT, produced by NFB for 2-year old CBC-TV. They were running behind and NFB called me to fill in. I had never before done ad lib of this sort. They were supposed to have an advance man to do research and provide points to be covered or some sort of script but that never materialized. There was no crew either, so I doubled on grip work, hauled equipment from setup to setup — couldn’t do the camera and be in front of it, too — though I’m sure NFB would have loved that.I was just naturally very interested in the ship and asked a lot of questions and it worked out fine. The ship had no air conditioning. We were on maneuvers in the Gulf Stream near Bermuda in August. The heat was a killer. I couldn’t sleep. I shared a cabin with a lieutenant, a really nice fellow. He said, “Hey, Andy, you’re a V.I.P. here, I could get you a cot on a deck.” There was a little deck at the rear below the flight deck. All lights were out on maneuvers. I had never seen so many stars in my life — and the sea was filled with phosphorescence — like millions of fire flies. I thought I had died and gone to heaven.

We only had one week on the Maggie making the documentary but I was tempted to sign up for life. The navy had turned me down once before. A buddy and I got terrible marks in high school in the spring ’45 so we ran down to the Navy Recruiting station in Toronto and asked to sign up. A wiseguy behind the desk said, “Leave your names and if Hitler attacks Toronto, we’ll give you a call.” (Hitler shot himself a week later)

A video editor friend up in Belleville found this video and wrote to me saying there was a fellow with my name in this video. I told him that was me 70 pounds ago. Great days.

The Wikipedia entry says:

HMCS Magnificent (CVL 21) was a Majestic-class light aircraft carrier that served the Royal Canadian Navy from 1948–1957. Initially ordered by the Royal Navy during World War II, the Royal Canadian Navy acquired the carrier as a larger replacement for its existing operational carrier. Magnificent was generally referred to as Maggie in Canadian service. Following its return to the United Kingdom in 1956, the ship remained in reserve until being scrapped in 1965.

Description and construction

The 1942 Design Light Fleet carrier was divided into the original ten Colossus-class ships, followed by the five Majestic-class ships, which had some design changes that accommodated larger and heavier aircraft. The changes reduced the weight of petrol and fuel storage by reducing them to 75,000 gallons, to offset the additional weight from strengthening of the deck to operate aircraft as heavy as 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg). Further improvements over the Colossus class included larger aircraft elevators (54 by 34 feet, 16 m × 10 m) and improvements made to internal subdivisions for survivability purposes and accommodations.

The ship was 698 feet (212.8 m) long with a beam of 80 ft (24.4 m) and a draught of 25 ft (7.6 m). The carrier displaced 15,700 long tons (16,000 t). The ship was powered by steam from four Admiralty three-drum boilers. This propelled two Parsons geared steam turbines driving two shafts creating 40,000 shaft horsepower (30,000 kW). Magnificent had a top speed of 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph).

The aircraft carrier was armed with 24 2-pounder and 19 Bofors 40 mm guns for anti-aircraft defence. Majestic-class carriers were fitted out with Type 281, Type 293 and two Type 277 radar installations. The ship had a complement of 1,100, including the air group.

The third ship of the Majestic class, Magnificent was ordered 16 October 1942. The order was placed with Harland and Wolff in Belfast who were also constructing the Colossus-class ships Glory and Warrior. Magnificent was laid down on 29 July 1943 with the yard number 1228 and launched on 16 November 1944.

April 16, 2020

The (temporary) return of “dazzle” paint schemes for the Royal Canadian Navy

Well, two RCN ships, if not the entire fleet … Joseph Trevithick reports for The Drive:

HMCS Regina in her dazzle camouflage paint taking part in Task Group Exercise 20-1 in April, 2020.

Canadian Forces photo via The Drive.

Air forces around the world will often give their aircraft specialized paint jobs to commemorate anniversaries and other notable occasions, but it’s far less common to see navies do the same thing with their ships. Recently, however, the Royal Canadian Navy’s Halifax class frigate HMCS Regina recently took part in a training exercise wearing an iconic blue, black, and gray paint job, commonly known as a “dazzle” scheme, a kind of warship camouflage that first appeared during World War I.

At the end of March 2020, Regina, and her unique paint job, had joined HMCS Calgary, another Halifax-class frigate, along with the Kingston-class coastal defense vessel HMCS Brandon and two Orca-class Patrol Craft Training (PCT) vessels, Cougar* and Wolf*, for Task Group Exercise 20-1 (TGEX 20-1) off the coast of Vancouver Island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. The training continued into the first week of April. TGEX 20-1 was part of Calgary‘s Directed Sea Readiness Training (DSRT) in preparation for that particular ship’s upcoming deployment.

Regina had first emerged in the dazzle scheme in October 2019 ahead of the U.S. Navy-led Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise, a massive naval training event that takes place every two years and includes U.S. allies and partners from around the Pacific region. It reportedly took 272 gallons of paint and cost the Royal Canadian Navy $20,000 to give Regina the dazzle treatment.

The frigate will wear the camouflage pattern until the end of 2020. The Royal Canadian Navy also painted up the Kingston-class HMCS Moncton, which is homeported in Halifax on the other side of the country, in a similar scheme. The paint job on both ships is in commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the end of the Battle of the Atlantic. This refers to the Allied fight to both enforce a naval blockade of Germany during World War II and secure critical maritime supply routes from North America to Europe. The battle officially ended with the surrender of the Nazi regime in May 1945.

* Wikipedia points out that the Orca-class are not formally commissioned ships in the RCN and therefore do not carry the designation “Her Majesty’s Canadian Ship” (HMCS).

March 23, 2020

Naval strategy versus naval tactics in the Battle of the Atlantic

Ted Campbell outlines how the Battle of the Atlantic was fought between the Kriegsmarine and the Royal Navy (and the Royal Canadian Navy and, eventually, the United States Navy) in World War 2:

… there is a rather thick, and quite blurry line between naval strategy and naval tactics. One Army.ca member used the Battle of the Atlantic to distinguish between two doctrines:

- Sea control ~ which was practised by the 2nd World War allies ~ mostly British Admirals Percy Noble and Max Horton in Britain and Canadian Rear Admiral Leonard Murray in St John’s and Halifax; and

- Sea denial ~ which was practised by German Admiral Karl Dönitz.

The difference between the two tactical doctrines was very clear. The strategic aims were equally clear:

- Admiral Dönitz wanted to knock Britain out of the war ~ something that he (and Churchill) understood could be done by starving Britain into submission by preventing food, fuel and ammunition from reaching Britain from North America. (We can be eternally grateful that Adolph Hitler did not share Dönitz’ strategic vision and listened, instead, to lesser men and his own, inept, instincts); and

- Prime Minister Churchill, who really did say that “the only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril“, who wanted to keep Britain fighting, at the very least resisting, until the Americans could, finally, be persuaded to come to the rescue.

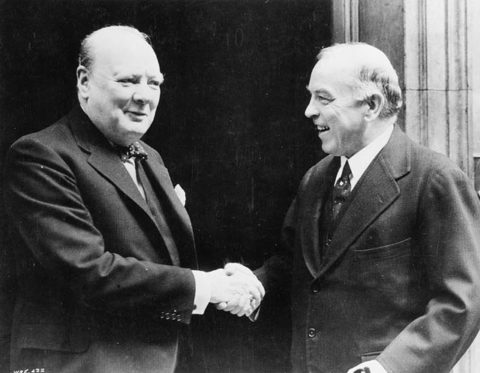

Prime Minister Winston Churchill greets Canadian PM William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1941.

Photo from Library and Archives Canada (reference number C-047565) via Wikimedia Commons.Canada’s Prime Minister Mackenzie King did have a grand strategy of his own. It was to do as much as possible while operating with the lowest possible risk of casualties ~ the conscription crisis of 1917 was, always, uppermost in his mind and he was, therefore, terrified of casualties. He mightily approved of the Navy doing a HUGE share in the Battle of the Atlantic ~ especially by building ships in Canadian yards and escorting convoys which he hoped would be a low-risk affair.

Churchill’s grand strategy was based on Britain surviving … there was, I believe, a “worst case” scenario in which the British Isles were occupied and the King and his government went to Canada or even India. But that has always seemed to me to be a sort of fantasy. The United Kingdom, without the British Isles, made no sense.

(While I believe that Rudolph Hess was, as they say, a few fries short of a happy meal, I think that he and several people in Germany believed that it might be possible to negotiate a peace with Britain which many felt was a necessary precursor to a successful campaign against Russia. The Battle of Britain (die Luftschlacht um England, September 1940 to June 1941) was, clearly, not going in Germany’s favour. Late in 1940, the Nazi high command had been forced to send a German Army formation to Libya to prevent a complete rout of the Italians. Malta still held out, meaning that Britain had air cover throughout the Mediterranean. In short, Britain was not going to go down unless it could be starved into submission ~ and in the spring of 1941, the Battle of the Atlantic was going in Germany’s favour. There was, in other words, some reason for Germans to believe that an armistice might be possible ~ freeing up all of Germany’s power to be used against the USSR.)

(But things were changing for the Allies, too. At just about the same time as Hess was flying to Scotland, then Commodore Leonard Murray of the Royal Canadian Navy, who had been in England on other duties, had met with and persuaded Admiral Sir Percy Noble, who liked Murray and had been his commander in earlier years, that a new convoy escort force should be established in Newfoundland and that it should be a largely Canadian force (with British, Dutch, Norwegian and Polish ships under command, too) and that it should be commanded by a Canadian officer. Admiral Noble insisted, to Canada, that Murray, who he liked, personally, and who had written, extensively, on convoy operations in the 1920s and ’30s, must be that commander. The establishment of the Newfoundland Escort Force, which would be more appropriately renamed the Mid Ocean Escort Force in 1942, was a key decision at the much-debated operational level of war which put an expert tactician (Murray) in command of a major force and allowed him (and Noble) to move closer to achieving Churchill’s strategic aim. The Battle of the Atlantic was not won in 1941, but it seemed to Churchill, Noble and Murray that they were a lot less likely to lose it, even without the Americans.)

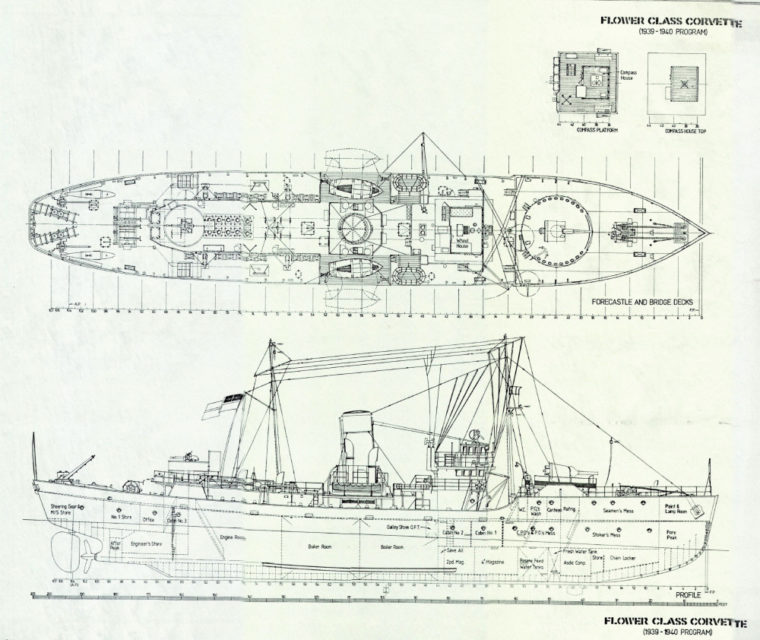

Diagram of the early Flower-class corvettes, via Lt. Mike Dunbar (https://visualfix.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/dreadful-wale-4/)

Anyway, the boundaries of strategy vs. the operational art vs. tactics were as thick and blurry in 1941 as they are today. The decision, taken in 1939, for example, to build little corvettes in the many British and Canadian yards that could not build a real warship was, in retrospect, a key strategic choice, but it was, at the time, totally materialist: just a commonsense, engineer solution to an operational problem ~ lack of ships. Ditto for the eventual decision, which had to be made by Churchill, himself, to reassign some of the big, long-range, Lancaster heavy bombers to Coastal Command. It was, once again, with the benefit of hindsight, a key strategic move, but at the time it would likely have seemed, to Capt(N) Hugues Canuel, the author of that Canadian Naval Review essay, to be materialistic, more concerned with how to use the resources available than with deciding what is needed.

I agree with Capt(N) Canuel that, by and large, Canadians have left strategic and even operational level thinking to first, the British and more recently the American admirals ~ Rear Admiral Murray being known, in the 1930s and early 1940s as a notable exception.

March 7, 2020

RCN’s Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ships delayed again

In the Ottawa Citizen, David Pugliese reports on the latest hold-up in getting the Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ships (AOPS) into the RCN’s hands:

The delivery of the first Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ship to the Royal Canadian Navy has been delayed once more and the arrival of the second ship has also fallen behind schedule.

In November, the Department of National Defence stated the first Arctic and Offshore Patrol Ships, or AOPS, was expected by the end of March.

That won’t be happening, DND confirmed to this newspaper.

The department can’t provide any specific details on a new delivery date for the ship being built by Irving Shipbuilding Inc. on the east coast. But it noted that delivery would happen sometime before June 21.

The first AOPS was to have been delivered in 2013, with Arctic operations set for 2015. But ongoing problems with the government’s national shipbuilding program and delays in awarding the contract continued to push schedules back.

There is some risk the first vessel could be delayed beyond the June timeframe, DND acknowledged. In addition, the department confirmed the delivery of the second AOPS has also fallen behind schedule. The scheduled delivery of the other ships could also slip.

“Lessons are being learned from the construction of the first ship, and are benefiting the construction of the second ship,” explained DND spokeswoman Jessica Lamirande. “However, as some inefficiencies are still being resolved, and because resources were focused on the first ship, delivery of the second ship has been delayed. The delivery timelines for the second to sixth ships are still being assessed, and updates will be shared once available.”

The second AOPS was supposed to be delivered in late 2020. The last of the six ships was supposed to arrive in 2024.

August 17, 2019

The “remarkably worthless” Sea Sparrow missile launchers on RCN Iroquois-class destroyers

Earlier this week, Tyler Rogoway posted a fascinating article about one of the original weapon systems installed on Royal Canadian Navy Iroquois-class destroyers. It was developed specifically for this class, and was eventually replaced with modern Mark 41 Vertical Launch Systems during the ships’ mid-life modernization refits:

From manually aimed box launchers, to automated ones like the Mk29 still in use today, to vertical launch variants, the Sea Sparrow was adapted for many different launching methods. Yet the strangest had to the one found on Canada’s Iroquois class. About seven years ago, someone who had worked with RIM-7s on U.S. Navy vessels told me about how nuts the Canadian launch system was that he had seen demonstrated in the late 1980s. In fact, he said it was so clumsy and slow reacting, that it largely defeated the main purpose of the missile system, at least in a multitude of circumstances. “Remarkably worthless” was the way he described it. I had long forgotten about this exchange until recently when pictures of this exact system popped up on the always lively Reddit page r/Warshipporn. At first, when I saw the images I was flabbergasted as to how weird the setup was, then the memory of the conversation hit me. This is what my contact was talking about!

Four Iroquois-class destroyers were commissioned between 1972 and 1973 and all served until 2005, with the last example being retired two years ago, in 2017. They featured the MKIII Sea Sparrow system fitted inside their forward deckhouse, with doors that opened up on each side and overhead swing-arm launchers carrying four missiles each (eight in total, four on each side) that extended out from their garage-like enclosure that hung out off the side of the ship strangely when at the ready. The whole arrangement looks like something far from conducive to high sea state, not to mention rocket blast from the missiles, or a combat environment, for that matter. 32 missiles were carried in all, with twelve at the ready on each side, but reloading the system as a whole was a slow process.

In addition, it’s said that the Hollandse Signaal Mk22 Weapon Control System wasn’t really up to the task and just deploying the missiles and warming up their guidance systems could take minutes or longer. All of this is far from ideal for what is supposed to have been a fast-reacting point defense system capable of quickly fending off sea-skimming anti-ship missiles that arrive with little warning from over the horizon.

July 28, 2019

“Fantasy Fleet” notions for the RCN

I hate to use the term “fantasy fleet” when linking to a Ted Campbell article … he’s far from being an obsessive who loves amassing lists of cool, gosh-wow hardware, as he’s a retired former army officer who actually does know what he’s talking about on military matters. I apply the term because no matter how sensible and practical these suggestions are (and I largely agree with them on those terms), there is no chance the current government or even a Conservative government under the Milk Dud could stand the political heat they’d take for devoting the kind of ongoing investment a fleet renewal and expansion like this would generate:

The Kingston-class Maritime Coastal Defence Vessel (MCDV) HMCS Moncton in Baltimore harbour for Sailabration 2012.

Photo by Acroterion via Wikimedia Commons.

… Canada’s 25 years old Kingston class vessels have a range of up to 5,000 nautical miles and can carry unmanned aerial vehicles, but they are slow and are designed for underwater warfare, being fitted with specialist payloads to look for mines and other things on the seabed … The Royal Canadian Navy has said, in the past, that it needs 25± surface combatants (the Navy uses the term “bottoms” when it means surface ships) and Canada has, now, 12 of the 30-year-old (but still lethal) Halifax class frigates and we also have, right now, 12 very useful little Kingston class ships, too. Canada plans (hopes?) to have 12 of the new Type 26 ships in the future, plus 5 of the very large (6,500+ tons) Harry DeWolf class Arctic patrol ships … so we are going from 24 down to 17?

A Chilean navy boarding team fast-ropes onto the flight deck of RCN Halifax-class frigate HMCS Calgary (FFH 335) during multinational training exercise Fuerzas Aliadas PANAMAX 2009.

US Navy photo via Wikimedia Commons.

My guesstimate is that a proper Canadian Navy needs, in addition to supply/support ships, at least:

- 2 or 3 large (25,000± tons) helicopter carrying “destroyers,” (in fact, small aircraft carriers) perhaps like the modern Japanese Izumo-class multi-purpose “destroyers” (pictured below) to conduct multi-purpose operations, including carrying combat-ready specialized amphibious warfare trained soldiers, on a global basis;

- 8 to 12 Type-26 destroyer-frigates (below) ~ I believe (guess) they will also be named for Canadian provinces, cities or rivers or something;

- 6 to 10 modern corvettes (a modern Dutch design is pictured below), 1,500-ton to 2,500-ton vessels, with a 5,000± nautical mile range, each able to carry a helicopter or, at least, a large unmanned aerial vehicle;

KRI Diponegoro (pennant number 365) of the Indonesian navy. The Sigma (Ship Integrated Geometrical Modularity Approach) class is a Dutch modular design that can be built in OPV, corvette, or frigate variants. In 2019, ships of this class are in service with Indonesia, Morocco, and Mexico.

Photo by Wim Kosten via Wikimedia Commons.- 6 to 10 special purpose, ocean-going (i.e. with a range measured in thousands, not hundreds of nautical miles) underwater warfare vessels to replace the Kingston-class ships; and

The lead vessel of the Orca-class in the Gulf Islands on officer training in August, 2007. She is not a commissioned naval ship, so does not bear the HMCS designation. Orcas are not generally armed, but the foredeck has been strengthened to allow an M2 12.7mm machine gun to be mounted if necessary.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.- 8 to 12 armed “training” ships, about 250 tons (about the same as the Finnish Hamina class) to replace the (fairly new) Orca class vessels, which are not warships. These ships would be, primarily, training vessels, for which there is, always, a pressing need but they could, in emergencies, be used for coastal, constabulary patrol and search and rescue duties, too. The important thing is that they would be real warships, in commission, armed about as well as the Harry DeWolf class ships (which would enhance their training value, too) and, therefore, able to “fight.”

In his ideal world (i.e., not the one we’re living in at the moment), that would be the RCN’s combat fleet. Submarines, logistical support vessels, and (lots of) helicopters would also be required, which would further put this shopping list out of consideration for a Canadian peacetime government.

One thing to keep in mind for most of us civilians, is that warships operate in very rough environmental conditions even in peacetime, and require much more in the way of maintenance and service than your car or pleasure boat. This is why, even if you have a dozen ships “in commission”, you’ll likely only have eight of them available for deployment as the others will be in various states of maintenance and repair. For operations far from home, you really need three ships for each one actually deployed on active service, to account for the back-shop work to keep the ships afloat, fully staffed, and fully capable, plus transit time for the ship itself getting to and from the area of operations, and adequate leave and out-of-combat rest and recreation for the crews.

June 27, 2019

$26B, $56B, $70B, and pretty soon you’re talking real money

The headline refers to the constant upward movement of various estimates on how much the Canadian government will be required to spend on the Canadian Surface Combatant program. In shorthand, that’s the money required to replace the Royal Canadian Navy’s current fleet of 12 frigates and the Iroquois-class destroyers that have already been retired from service. The Halifax-class frigates began entering service in the early 1990s and were designed to operate for about thirty years, meaning the RCN needs replacements to start coming into the fleet in the mid-2020s. The government initially budgeted around $26B for fifteen ships in 2008, but as with so many military equipment programs, no actual steel has been cut to begin building the new ships … in fact the design was only formally agreed in October 2018 and not signed (due to a lawsuit from one of the losing bidders) until February of this year. We’re still probably 2-3 years away from construction of the first ship in the class beginning, which will mean the Halifax class will have to remain on duty for longer (and older ships require more frequent and more expensive maintenance).

A Chilean navy boarding team fast-ropes onto the flight deck of RCN Halifax-class frigate HMCS Calgary (FFH 335) during multinational training exercise Fuerzas Aliadas PANAMAX 2009.

US Navy photo via Wikimedia.

The Department of National Defence most recently estimated up to a $60B final bill, but the Parliamentary Budget Office estimate was $70B (an increase of $8B over a two-year span), and there’s no reason to assume that things will magically get cheaper between now and whenever Irving Shipbuilding starts construction of the first new ship. David Pugliese reports:

… it could be years before the real cost to taxpayers for the mega-project is actually known as the project is just getting started.

The PBO report warned that any delays in building the first ship will be costly. A delay of one year, for instance, could increase costs by almost $2.2 billion, it added.

The federal government hopes to begin building the ships starting in the early 2020s.

Pat Finn, the head of procurement at DND, said the PBO estimates largely align with what the department figures as the cost of the program. He noted that unlike the PBO, the department does not consider tax in its cost figures. That is because those fees ultimately go back to the federal treasury.

But he also agreed with the PBO on the concern about added cost if the project is delayed. “That is a key one for us. It’s something we’re watching carefully,” said Finn, assistant deputy minister for materiel.

The CSC program is currently in the development phase. The government projects the acquisition phase to begin in the early 2020s with deliveries to begin in the mid-2020s. The delivery of the 15th ship, slated for the late 2040s, will mark the end of that project.

The Liberal government announced in February that it had entered into a contract with Irving Shipbuilding to acquire new warships based on the Type 26 design being built in the United Kingdom. With Canada ordering 15 of the warships, the Royal Canadian Navy will be the number one user of the Type 26 in the world.

The United Kingdom had planned to buy 13 of the ships but cut that down to eight. Australia plans to buy nine of the vessels designed by BAE of the United Kingdom.

The entry of the BAE Type 26 warship in the Canadian competition was controversial from the start and sparked complaints the procurement process was skewed to favour that vessel. Previously the Liberal government had said only mature existing designs or designs of ships already in service with other navies would be accepted, on the grounds they could be built faster and would be less risky. Unproven designs can face challenges as problems are found once the vessel is in the water and operating.

But the requirement for a mature design was changed and the government and Irving accepted the BAE design, though at the time it existed only on the drawing board. Construction began on the first Type 26 frigate in the summer of 2017 for Britain’s Royal Navy, but it has not yet been completed. Company claims about what the Type 26 ship can do, including how fast it can go, are based on simulations or projections.

BAE Systems released this artist’s rendition of the Type 26 Global Combat Ship in 2017, which is the design selected by the Canadian government for the Canadian Surface Combatant program.

(BAE Systems, via Flickr)

Ted Campbell commented on the report:

I’m not sure the new ($70 Billion) figure is a terribly useful number for taxpayers like you or me or for policymakers, either. I’m not convinced that DND, itself, much less the whole of government, including the PBO, has a common, coherent understanding of “life-cycle costs,” and I’m damned sure neither the media nor 99.99% of Canadians has one. I’m glad to see that the government includes “the cost of project development, production of the ships, two years of spare parts and ammunition, training, government program management, upgrades to existing facilities, and applicable taxes” but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. These ships are going to be in service for 35± years and they are going to cost money to own and operate every hour of every day and I hope someone is programming ongoing costs (running costs, routine maintenance, upgrades and refits and life extension projects and even disposal) into the long term defence budget guesstimates.

Good management says that the DND budget should be pretty well fixed for the next year or two, fairly firm (even allowing for a change in government) for four or five years beyond the end of the next fiscal year it should be and a reliable planning guide for the next decade or even two. In other words, DND should have a pretty good idea about what it will cost to operate itself, pretty much as it is now, for a generation. I expect (hope, anyway) that defence planners have a “Christmas wish list” of capabilities they want to add or improve/increase (with costs attached) should a defence friendly government ever materialize in Canada or, sadly but more likely when, not if, the need arises.

He also points out the hidden truism about huge government purchases:

… from 1950 to 1958 the several hundred Canadair F-86 Sabre jets that Canada bought for the RCAF was, probably, “the largest single expenditure in Canadian government history,” then from the early 1950s until 1964 the production of 20 destroyers (DDE and DDH) of the St Laurent, Restigouche, Mackenzie and Annapolis classes (all based on one, baseline, design) was, almost certainly, “the largest single expenditure in Canadian government history,” and I know for a fact that the purchase decision (in 1980) of 138 CF-18 Hornets made it “the largest single expenditure in Canadian government history.” The simple fact is that the costs of high-tech aircraft, howitzers, tanks, radios and, especially, ships, keep climbing far faster than inflation and if, as we must, we want our armed forces to be adequately equipped then we need to accept higher costs … especially if we want to build ships in Canadian yards, employing Canadian workers.

May 13, 2019

The political persecution of Vice-Admiral Norman

Conrad Black on the recently stayed prosecution of the former Vice-Chief of the Defence Staff, Vice-Admiral Mark Norman:

The RCMP, the same Palooka force that brought us the ghastly fiasco of the trial and resounding acquittal of Senator Mike Duffy, alleged that Vice Adm. Norman was the source of press leaks, and searched his house with a warrant in January 2017, a fact that was also mysteriously leaked to the press. He was suspended with full pay, and finally, in March of 2018, he was charged with a criminal breach of trust. The government barred him from the benefit of the loan of money for legal fees to accused government employees pending judgment, a capricious attempt to starve him into surrender.

Neither the media, usually pretty quick to jump on the back of any defendant, nor any other serious observers, believed the defendant, who started in the navy as a diesel mechanic and rose for 33 years to commander of the fleet and then serve as vice-chief of the defence staff, would do such a thing, or that the RCMP had any real evidence. It didn’t, inciting the suspicion that the Mounties, if they can’t raise their game, should stick to musical rides and selling ginger ale, and reinforcing the view that the Armed Forces should be funded properly, and not just in phony announcements every few years of naval construction and army and air force procurement programs that don’t happen. And It is, in any case unacceptable that police corporals get warrants to search the home of the second highest military officer in the country on grounds that are eventually shown to be unfounded.

It appears to be clear that exculpatory evidence was withheld by the prosecutors, deliberately or otherwise. Outgoing Liberal MP and parliamentary secretary Lt. Gen. (Rt.) Andrew Leslie (a grandson of two former defence ministers, Gen. Andrew McNaughton and Brooke Claxton), had announced he would testify on behalf of Vice Adm. Norman. The prime minister ducked out of question period for two days as this contemptible abuse of prosecution collapsed. Instead, he should, if conscientiously possible, have blamed it on the former attorney general, Jody Wilson-Raybould. That would have been believable, given some of her other antics in that office.

If he can’t do that, then this rotten egg falls on him and could be a politically mortal blow. The SNC-Lavalin affair was an attempt to save jobs in Canada and avoid over-penalization of a successful international company where there is a legal right for the justice department to choose between a fine and criminal prosecution. It was bungled, a ludicrous amateur hour that brought down senior civil servants and led to expulsions of ex-cabinet ministers as Liberal MPs, but it was not a show-stopper unless the prime minister lied to Parliament.

This appears to be a malicious and illegal prosecution of a blameless senior serving officer, who fought his corner as a brave man must. If that is what it is, heads should roll, not of scapegoats, token juniors, or fall-guys, but of those responsible for this outrage.

May 9, 2019

MV Asterix delivers for the Royal Canadian Navy and breach of trust charge is dropped

Amid rumours that the Trudeau government is contemplating dropping the charge against Admiral Mark Norman, Matthew Fisher retweeted a link to his article from last year, praising the ship and suggesting that it should be renamed in honour of the man who did everything he could to get the RCN’s only current replenishment ship to sea:

Aboard MV Asterix and HMCS Charlottetown – The Trudeau government would have fits, but the Royal Canadian Navy should consider renaming the MV Asterix the HMCS Admiral Mark Norman.

The controversial new replenishment ship, which entered service on time and on budget this past January, has been performing brilliantly for the navy during sea trials. That was the unanimous opinion of sailors on HMCS Charlottetown and on MV Asterix after a series of refuelling exercises with the Canadian frigate and American destroyers during a hunt for three U.S. nuclear subs that I witnessed recently in the Caribbean.

The only hiccup during the five-day war game was on the American side. The crew on one of the destroyers was unable to establish a good seal on the fuel probe Asterix sent over as the vessels sailed at 15 knots in a two-metre sea with about 30 metres of water between them. However, it only took about 10 minutes to fix the problem.

Vice-Admiral Mark Norman, who ran the RCN before becoming the military’s second-in-command, strongly supported leasing or buying Asterix. The admiral was suspended early last year and subsequently charged with breach of trust for allegedly violating cabinet confidences. He is accused of passing on information pertaining to doubts that the Trudeau government was believed to have had about leasing the vessel. Although there were strong signals that it wanted out of the deal, the government eventually decided to honour a contract that Davie had with the Harper government to lease Asterix for five years at will be a cost of $677 million,according to the Globe and Mail.

“I think the Asterix is fantastic,” said Chief Petty Officer 2nd Class Mark Parsons, the Charlottetown’s chief bosun’s mate, who oversaw two approximately hour-long, problem-free fuel transfers from the tanker to his warship. “We have missed that capability since (HMCS) Preserver was retired in 2014” because of electrical problems and corrosion.

Parsons’ opposite number on Asterix, CPO2 Steve Turgeon, served on the 48-year old Preserver until 2013. Since January he has been training four deck crews of 11 navy sailors each to handle refuellings. This has allowed Canada to once again be an independent blue-water navy after several years in which it depended on NATO allies and leased Chilean and Spanish navy tankers for fuel at sea. A fresh group of navy sailors has just begun training on the Asterix, which is participating with two Canadian frigates in the vast U.S.-led, 25-nation Rim of the Pacific naval exercise off Hawaii this month.

And on the legal front:

Just saw Admiral Mark Norman walk into Ottawa courthouse with his legal team. Andy Leslie, Liberal MP & retired three star general who was going to testify for Norman, gave the admiral a bear hug.Norman told media army: "it's a beautiful day."

It is for him but not for PM Trudeau— Matthew Fisher (@mfisheroverseas) May 8, 2019

Later in the day, the news was finally made official: the government has dropped the charge and Vice-Admiral Mark Norman wants his job back:

The newly exonerated Vice-Admiral Mark Norman says he was alarmed by the persistent belief among senior government officials that he was guilty, and that their false assumptions took a significant financial and emotional toll on him and on his family.

On Wednesday, prosecutors stayed the single criminal charge of breach of trust laid against Norman, a major victory for the senior naval officer who has always maintained his innocence in the face of allegations he leaked confidential information about a project to procure a supply ship for the Royal Canadian Navy. In announcing the decision, Crown prosecutor Barbara Mercier told the court it was necessary in part due to new evidence the defence produced in March.

“This new information definitely provided greater context to the conduct of Vice-Admiral Norman, and it revealed a number of complexities in the process that we were not aware of,” Mercier said. “Based on the new information, we have come to the conclusion that given the particular situation involving Vice-Admiral Mark Norman, there is no reasonable prospect of conviction in this case.”

She did not provide any details on what exactly that information was.

The announcement ends the two-year legal battle against the officer and heads off what would have been a politically explosive trial for the Liberal government in the middle of a federal election campaign.

A fascinating little detail is also reported:

[Admiral Norman only] learned from a reporter’s question that Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan had announced the government would pay for his legal fees. “Wow,” was all he could muster in response. In 2017, the Department of National Defence had denied Norman’s request for financial assistance, concluding he was likely guilty.

So even though they’re finally making the right gestures, they still manage to be as ungracious as humanly possible while doing so. It’s not the kind of reputation you’d want to encourage.

April 21, 2019

Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic, part 13

Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-5-edited/1453).

This will be the last installment I’ll be re-posting here, as discussion with Alex after I obtained a copy of Marc Milner’s North Atlantic Run made it clear that the bulk of the writing up until this point had actually been copied directly from Milner’s book and only lightly paraphrased and re-ordered by Alex. I’ve gone back over the earlier posts and, to the best of my ability, marked all the direct quotes and provided acknowledgements appropriately.

Sources:

- Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos are in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Earlier parts of this series:

Part 1 — Canada’s navy before WW2

Part 2 — The Admiralty takes control

Part 3 — The professionals and the amateurs

Part 4 — 1940: The fall of France, the battle begins, and the RCN dreams of expansion

Part 5 — The RCN’s desperate need for warships

Part 6 — New ships, new challenges

Part 8 — Expansion problems: not enough men for not enough ships

Part 9 — Early-to-mid 1941, The Rocky Isle in the Ocean

Part 10 — The Newfoundland Escort Force and the Canadian corvettes

Part 11 — “Chummy” Prentice and the NEF

Part 12 — Staff needed, training needed, and Commodore Murray’s thankless tasks

Part 13 — Convoy operations, the Americans, and 1941 Drags On

Marc Milner discusses convoy organization in North Atlantic Run:

The organization and sailing of convoys was co-ordinated by the Admiralty’s world-wide intelligence network, of which Ottawa was the North American centre. The assembling of shipping in convoy ports was the responsibility of local NCS staffs working in conjunction with the regional intelligence centre, through which all communication with other regional centres passed. The actual organization of the convoys, issuing code books, charts, special publications, arrangement of pre-sailing conferences, passing out sailing orders, and so forth, was all the work of the NCS.

[Editor’s Note: The command structure for typical Atlantic convoys is discussed in Arnold Hague’s excellent reference work The Allied Convoy System 1939-1945: Its organization, defence and operation:

In typical British fashion, control of the convoy was twofold. Direct control of the convoy rested with the Convoy Commodore, its protection with the Senior Officer of the Escort (referred to in the RN as SOE). As the escort commander was inevitably junior to the Commodore, it was laid down that the Commodore had no right of intervention with the escort, and that the SOE could, if he became aware of circumstances requiring it, give a mandatory instruction to the Commodore. A good deal of tolerance and understanding between the two officers was therefore essential. In fact, friction was minimal, co-operation normally of a high order and the whole system remarkably effective, with the Commodore dealing solely with the merchant ships of the convoy. The SOE intervened (or detailed another escort) at the specific request of the Commodore to provide any assistance required in controlling the convoy.

The divided command system should be seen in the context of the experience of the two commanders. The Commodores, all elderly men, had practical, personal, experience of the problems of coal fired ships from their younger days. As almost all had started their Commodore’s service in the first months of the war they had considerable personal experience of the problems of the Masters whom they led. The escort commanders, much younger officers, lacked that personal knowledge, and the opportunity to obtain it. The system worked in practice, with only rare cases of a personality clash between Commodore and SOE or Commodore and ships’ Masters. In such instances, the Admiralty could exercise its prerogative of dispensing with a Commodore’s services, or appointing him elsewhere. In the only case known to the writer, the offending Commodore, described as “an intolerant personality who greatly upset the Masters of ships in the convoy,” was appointed elsewhere after a short interval. He served the next five years in a single, vital appointment with distinction and great efficiency and, as the Commodore commanding the working-up base at Tobermory in Western Scotland, he was responsible for the training of all newly built or re-commissioned British escort vessels during 1940-45. Indeed not a few RCN and Allied escorts also passed through his hands. He contributed to a very large extent indeed to the efficiency of such escorts and his name became wiedly known and one to respect and admire. His name? Vice-Admiral Sir Gilbert O. Stephenson, also known as the “Terror of Tobermory”.

[…]

Convoy Commodores were drawn from a list of volunteers to serve either with Ocean or Coastal convoys. For the former, the choice was made from retired Flag Officers and Captains of the Royal Navy who were appointed as Commmodores 2nd Class in the Royal Naval Reserve for the period of their duty. … Almost every Commodore was aged over sixty when the commenced his appointment, some older, and their retired ranks varied from Admiral to Lieutenant-Commander. … Commodores for the North Atlantic routes were drawn from a pool of less than 200 who served almost exclusively in that ocean. … Russian convoys drew their Commodores from the North Atlantic pool. Convoy systems organized by the Royal Australian and Royal Canadian Navies, principally coastal, were provided with Commodores appointed by those Services.

All Commodores had the right to request reversion to non-active service at any time, while the Admiralty retained the right (and occasionally exercised it) to retire a Commodore from service.

Commodores were assisted in their duties by a Vice-Commodore and, on occasions, by one or more Rear-Commodores. A Vice-Commodore could be either a Commodore RNR from the pool serving as an assistant or the Commodore of another convoy that had joined at sea. … In all other instances the Vice- and Rear-Commodores were Masters of ships in the appropriate convoy. Their duty was to assist the Commodore and to assume his duties should he be lost during the convoy.

Commodores were accompanied by a staff: a Yeoman of Signals (a Petty Officer of the Communications Branch), three Convoy Signalmen and usually a Telegraphist. They carried considerable responsibility and were, without exception, highly efficient visual signallers. It was also usual to provide the Vice-Commodore with two Convoy Signalmen to assist him in his duties.

In large trans-Atlantic convoys the commodore sailed front and centre, usually in a large ship which was well appointed for visual and wireless communications with the rest of the convoy and equipped for direct wireless communication with shore authorities. The commodore was also the crucial link between the convoy and its escort. Although the escort commander was ultimately responsible for the safe and timely arrival of the convoy, in practice he and the commodore worked as a team. The vice- and rear-commodores, where needed, were stationed in stern positions on the outer columns of the convoy. Each had his own small staff, largely signallers. Interestingly, the majority of convoy signallers in the North Atlantic by 1941 were RCN.

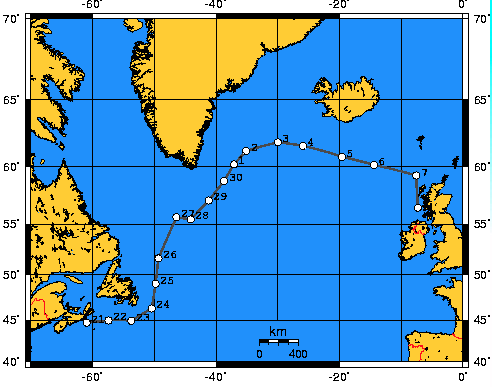

Marc Milner outlines convoy routing in North Atlantic Run:

Once the convoy cleared the outer defences of the harbour, it became the responsibility of the escort forces. Its routing, however, was laid down prior to sailing by the RN’s Trade Division (shared with the USN after the American entry into the war), which prescribed a series of points of longitude and latitude through which the convoy was to pass. Minor tactical deviations within a narrow band along the convoy’s main line of advance were permitted the SOE, but major alterations of course remained the prerogative of shore authorities. The ideal routing, one towards wich the Allies moved much more slowly than they would have liked, was one simple “tramline” along the most direct course between North America and Britain — the great circle route. For a number of reasons tramlines were not feasible until 1943. For the greater portion of the period covered by this study the object of routing remained simple avoidance of the enemy, within the limits of air and sea escorts.

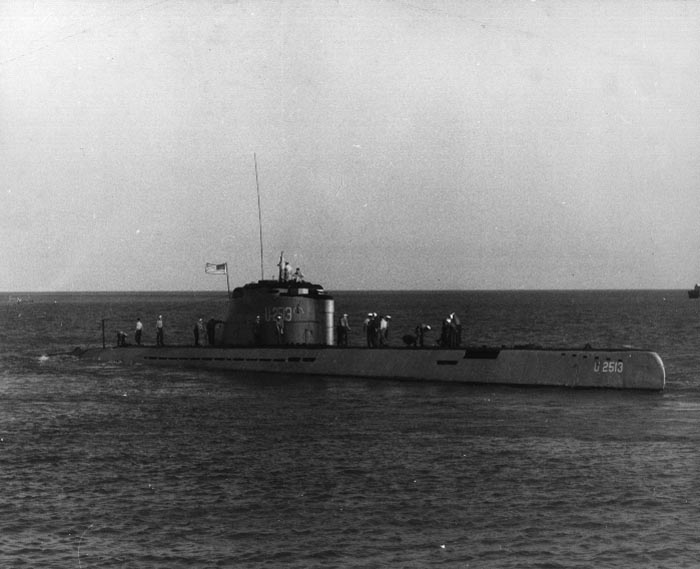

Convoy chart for convoy HX-134, departed on 20 June, 1941, arrived in Liverpool 9 July, 1941.

Image from the Convoy Web Convoy Charts page – http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/extras/index.html

The fast and slow convoy system had undergone some changes by mid-1941. Fast convoys from Halifax were still faster than 9 knots, but ships capable of moving faster than 14.8 knots were routed independently now. Slow convoys from Sydney, Cape Breton were ships capable of speeds between 7.5 and 8.9 knots. Their slow speed drew together a decrepit class of aged tramps, and there was initially no plan to convoy them through the winter. It soon became clear to the staff that all merchant shipping below a certain speed needed to be convoyed, otherwise the loss rate was far too high. For the ships and crews of the escort groups it was a thankless task: slow convoys were notorious for ill-discipline and inattention to signals. The older, slower ships were prone to excessive smoke (endangering the whole convoy by making easier to detect at a distance), breaking down, straggling (falling behind the convoy, beyond the protective screen of escorts sometimes to the point of losing contact with the convoy altogether), or even sailing ahead of the convoy “if stokers happened upon a better-than-average bunker of coal”. Slow convoys were said to more often resemble a mob than an orderly assemblage of ships, and their slow speed made evasive action difficult, if not impossible.

Unidentified signals personnel at the flag locker of the armed merchant cruiser HMCS Prince David in Halifax, Nova Scotia, January 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-104500

Marc Milner, North Atlantic Run:

By the time [Commodore] Murray arrived to take command of NEF it had grown to seven RN and six RCN destroyers, four RN sloops, and twenty-one corvettes, all but four of them RCN. The Admiralty would have liked even more committed to NEF. Indeed, in early July the Admiralty proposed to NSHQ that Halifax be virtually abandoned as an operational base and that the RCN’s main effort be concentrated at St John’s. Naval Service HQ might have expected grander British plans for St John’s when the Admiralty recommended that Commodore Murray command NEF instead of the RCN’s initial choice, Commander Mainguy. For practical reasons, however, concentrating the entire fleet at St John’s was impossible. In the summer of 1941 there were not enough facilities to support NEF, let alone the RCN’s whole expansion program, and it would be a long time before this situation was reversed. The Naval Council did not debate long before the idea was dismissed as impractical. None the less, subtle British pressure to increase the RCN’s commitment to St John’s was continued, in large part because the RN wanted to eliminate its involvement in escort operations in the Western Atlantic. In August, for example, the Admiralty advised the RCN that it preferred to deal with only one operational authority in the Western Atlantic, CCNF. The pressure, in combination with a serious German assault on convoys in NEF’s area by the late summer, proved successful. Despite growing USN involvement in convoy operations in the Western Atlantic, fully three-quarters of the RCN’s disposable strength was assigned to NEF by the end of the year. In spring of 1941, however, the RCN was unprepared to make such large-scale commitments.

One week after Murray assumed his post as CCNF, NEF fought its first convoy battle. Ironically, the confrontation was brought about by the increasing effectiveness of Allied convoy routing as a result of the penetration of the U-boat ciphers in May. Excellent evasive routing so reduced the incidence of interception that the U-boat command, out of frustration, broke up its patrol lines and scattered U-boats in loose formation. This made accurate plotting by Allied intelligence much more difficult and consequently made evasive routing less precise.

The first action against enemy submarines for the NEF occurred on the 23rd of June, 1941. Convoy HX-133 comprised fifty-eight ships eastbound from Halifax escorted by the destroyer HMCS Ottawa (SOE, Captain E.R. Mainguy) and the corvettes, HMCS Chambly, Collingwood, and Orillia. At some point during the day, the convoy was sighted by U-203, which communicated the convoy position to U-boat command and continued to shadow from a distance. U-203 attacked on the night of 23-24 June, easily penetrating the thin screen of escorts to sink a merchant ship. The SOE found it impossible to co-ordinate the escorts’ defence or to direct any search for the submarine because the corvettes were not fitted with radio telephones and their wireless sets were unable to reliably stay in communication with the SOE. Only Chambly logged receiving signals from Ottawa, but only half of them. On the 26th, Ottawa established an ASDIC contact and attacked and two of the corvettes came to assist, Commander Mainguy instructed the corvettes to stay and keep the U-boat submerged while the destroyer re-joined the convoy. The message, sent by message light, was only partially received, and the corvettes could not get the message repeated. Unable to determine what the order was, both ships broke off the action and returned to the convoy in turn. The escort group was eventually reinforced by RN ships, and although HX-133 lost six merchantmen, the RN escorts sank two of the attacking U-boats. These Canadian problems were lamentable, but hardly unexpected. As Joseph Schull, the RCN’s official historian, concluded, “no one could have expected it to be otherwise”.

Marc Milner picks up the story in North Atlantic Run:

In the meantime, Captain (D), Greenock’s stern criticism of the Canadian corvettes found its way to NSHQ, accompanied by a covering letter from Captain C.R.H. Taylor, RCN, who had succeeded Murray in London as CCCS. Taylor noted that the poor state of readiness of the corvettes stemmed from the fact that they were manned and stored for passage only. Deficiencies could not be made up from the RCN’s UK manning pool since most of the men who were committed to it were in fact still aboard the ships. Taylor also noted that the poor quality of officers, especially COs, had been pointed out in April and that they would never have been assigned if the ships had commissioned permanently. It was heartening to note, however, that Hepatica, Trillium, and Windflower, through remedial work and extra effort, were worked up “to a state of efficiency which the Commodore Western Isles reported as surpassing many RN corvettes”.

View of HMCS Annapolis from HMCS Hamilton, 30 August, 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/PA-104149Naval Service HQ was therefore well braced when a follow-up letter from the Admiralty arrived several days later. The letter took a conciliatory view of Canadian difficulties, noting that these seemed to be “essentially similar to those occasionally experienced with the RN corvettes and trawlers”. To overcome these the Admiralty advised of three means employed by the RN. If the officers and men were competent and responsive, simply prolonging the length of work-up usually sufficed. If the officers were incompetent or otherwise unsatisfactory, they could be replaced by new ones drawn from a manning pool. Similarly, inefficient or unsuitable key ratings could be replaced by men drawn from a pool maintained for this purpose. In its concluding remarks the letter cautioned that corvettes commissioning and working up in Canada were likely to display a wide variation in efficiency, and warned that at this point, with ships stretched to provide continuous A/S escort in the North Atlantic, “no reduction in individual efficiency can be safely accepted”. This was true enough, but it contradicted what the Admiralty had said to the RCN in April, when the issue of manning the ten “British” corvettes had been resolved.

While the Admiralty clearly felt that it was offering the RCN a workable set of solutions, the suggestions contained few alternatives for the Canadians. In sum, the RCN was hard pressed just to find men with enough basic training in order to get the corvettes to sea. Producing a surplus of specialists — of any kind — was out of the question. Nelles, in his draft reply to the Admiralty, pointed out that all experienced officers and men were already committed either to new ships or to the new RCN work-up establishment, HMCS Sambro, at Halifax. Future prospects looked equally grim. Spare HSD ratings (the highest level of ASDIC operator, of which there was to be one per corvette) would not be available until the spring of 1942, a prognosis even Nelles considered optimistic. And no trained RCN commanding officers or first lieutenants could be spared for some time to come. In short, a pool of qualified and disposable personnel was out of the question. If the RN wanted to loan experienced personnel until they could be replaced by the RCN, such help would be “greatly appreciated”. The only other options were prolonged work-ups or some form of ongoing training. Aside from that, Canadian escorts had to make do. RCN escorts sent to work up at Tobermory through 1941 continued to arrive in an unready state, though here is no indication that these were any worse off than corvettes retained for work-up in Canada. The state of ships arriving in Tobermory not only resulted in “much excellent training [being] lost”; it did little to enhance the RCN’s already tattered image within the parent service.

[Editor’s Note: The training at Tobermory really was both intense and nerve-wracking for RN and RCN crews alike, as James Lamb recounts in The Corvette Navy:]

… the really soul-testing experience, the one that every old corvette type still recalls today with a shudder, came with the two-week work-ups for newly commissioned ships, designed to make a collection of odds and sods into an efficient ship’s company. There were such bases at Bermuda, St. Margaret’s Bay, and Pictou on the Canadian side, but the one that really left a lot of scar tissue was the old original, the Dante’s Inferno operated at Tobermory on the northwest coast of Scotland by the redoubtable Vice-Admiral Gilbert Stephenson, Royal Navy. This legendary character, variously known as “Puggy”, “The Lord of the Isles”, or more commonly “The Old Bastard”, inhabited a former passenger steamer, The Western Isles, which lay at anchor in the quiet, picturesque harbour, surrounded by a handful of newly commissioned corvettes, like a spider surrounded by the empty husks of its victims. He was a daunting sight, smothered in gold lace and brass buttons, with a piercing blue eye that could open an oyster at thirty paces, and tufts of grey hair sprouting from craggy cheeks, and he preyed like some ravening dragon upon the callow crews and shaky officers served up to him at fortnightly intervals.

At the end of each day, an exhausted crew would tumble into their hammocks, but there was no assurance of uninterrupted slumber. On the contrary; the monster stalked its unwary prety by dark as well as by light, and seldom a night passed without an alarm of some sort. For the Admiral delighted in midnight forays; more than one commanding officer was shaken awake to find himslef staring into the piercing eyes of a malevolent Admiral and learn that his gangway had been left unportected, that his ship had been taken, and that his kingdom had been given over to the Medes and the Persians.

But occasionally — just occasionally — the ships got a little of their own back. There was the occasion when the Admiral in his barge, lurking soundlessly under the fo’c’sle of what he hoped to be an unsuspecting frigate, waiting for the sailor whom he could hear humming to himself on the deck above to move on, suddenly found himself being urinated on, “from a great height”, as gleeful narrators related the story in a hundred rapturous wardrooms. There was the other frigate he boarded one dark night only to be set upon by a ferocious Alsatian dog and fored to leap back into his boat, leaving, in the best comic-strip tradition, a portion of his trouser-seat aboard the ship, which ever after displayed the tattered remains as a proud trophy, suitably mounted and inscribed.

And there was the Canadian corvette sailor who worsted the fiery Admiral in a hand-to-hand duel. Coming aboard this ship, the Admiral suddenly removed this cap and flung it on the deck, shouting to the astounded quartermaster: “That’s an unexploded bomb; take action, quickly now!”

With surprising sang-froid, the youngster kicked the cap over the side. “Quick thinking!” commended the Admiral. Then, pointing to the slowly sinking cap, heavy with gold lace, the Admiral continued: “That’s a man overboard; jump to it and save him!”

The ashen-faced matelot took one look at the icy November sea, then turned and shouted: “Man overboard! Away lifeboat’s crew!”

The look on the Admiral’s face, as he watched his expensive Gieves cap slowly disappear into the depths while a cursing, fumbling crew attempted to get a boat ready for lowering, was balm to the souls of all who saw it.

Marc Milner, North Atlantic Run:

Although reports from both sides of the Atlantic indicated that the expansion fleet was badly in need of training and direction, its future looked bright in the summer of 1941. Corvettes operating from Sydney and Halifax as part of the Canadian local escort held up remarkably well to operations in the calmer months. A sampling of escorts based at Sydney in the months of August and September reveals startling statistics on the small amount of sea and out-of-service time logged by the new ships. Considerably less than half of their days were spent at sea, and this represented only about 56 percent of their seaworthy time. With so much time alongside, ships’ companies were able to keep up with teething problems. In the ships in question all time out of service was devoted to boiler cleaning. … Later, as operations crowded available time and spare hands crowded the mess decks to provide extra watches for longer voyages, the shorter period became routine. But it is significant that until the fall of 1941 the corvette fleet enjoyed considerable slack, in which it could make good its defects.