WARNING: If you’re an elected government official or if you’re attached to idealistic notions about such officials, do not read this commentary. It will offend you.

Ideally, government in a democratic republic reflects the will of the people, or at least that of the majority. Citizens vote for candidates whom they believe will best promote the general welfare. Victorious candidates, after pledging to uphold the Constitution, go to state capitals or to Washington, D.C., to do The People’s business — to undertake all the good and worthy activities that citizens in their private capacities cannot perform.

Sure, every now and then crooks and demagogues win office, but these are not the norm. Our system of regular, aboveboard democratic elections ensures that officials who do not effectively carry out The People’s business are thrown from office and replaced by more reliable public servants.

Trouble is, it’s not true. It’s a sham. Despite being called “the Honorable”, the typical politician is certainly no more honorable than the typical dentist, auto mechanic, Wal-Mart regional manager or any other private citizen.

Despite being referred to as “public servants”, politicians serve, first and foremost, their own personal political ambitions and they do so by pandering to narrow special interest groups.

Don Boudreaux, “Base Closings”, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, 2005-03-18.

May 20, 2024

QotD: “Selfless” public servants

January 20, 2024

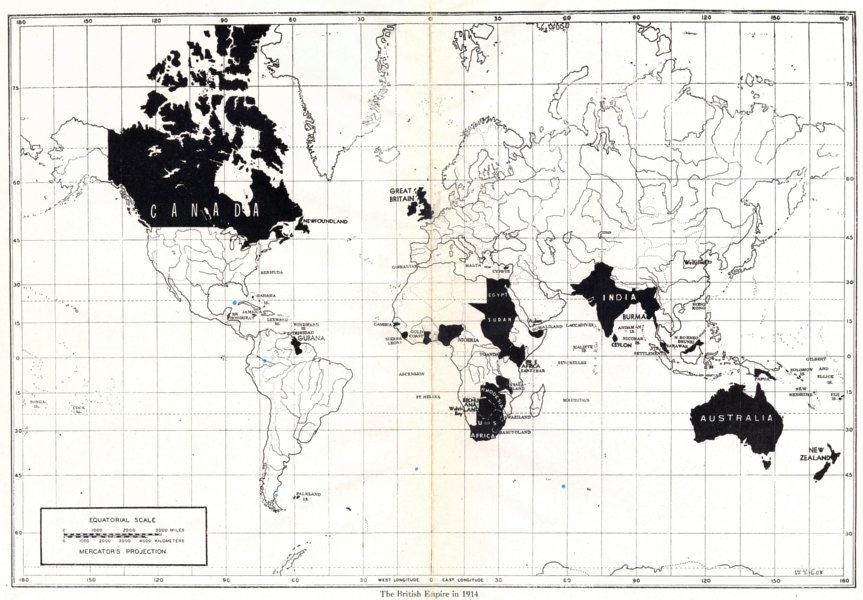

The British Empire would have failed a proper cost-benefit analysis

At the Institute of Economic Affairs, Kristian Niemietz is working on a paper on the economics of empire that, as he shows in this article, indicates that the empire was never a winning economic proposition for Britain as a whole, no matter how well certain well-connected individuals and companies benefitted:

But is it actually true that imperialism makes countries richer? Does imperialism make economic sense?

This question was already hotly debated at the heyday of imperialism. Adam Smith believed that the British Empire would not pass a cost-benefit test:

The pretended purpose of it was to encourage the manufactures, and to increase the commerce of Great Britain. But its real effect has been to raise the rate of mercantile profit, and to enable our merchants to turn into a branch of trade, of which the returns are more slow and distant than those of the greater part of other trades, a greater proportion of their capital than they otherwise would have done […]

Great Britain derives nothing but loss from the dominion which she assumes over her colonies.

He believed that Britain would be better off if it dissolved its Empire:

Great Britain would not only be immediately freed from the whole annual expense of the peace establishment of the colonies, but might settle with them such a treaty of commerce as would effectually secure to her a free trade, more advantageous to the great body of the people, though less so to the merchants, than the monopoly which she at present enjoys.

The liberal free-trade campaigner Richard Cobden agreed:

[O]ur naval force, on the West India station […], amounted to 29 vessels, carrying 474 guns, to protect a commerce just exceeding two millions per annum. This is not all. A considerable military force is kept up in those islands […]

Add to which, our civil expenditure, and the charges at the Colonial Office […]; and we find […] that our whole expenditure, in governing and protecting the trade of those islands, exceeds, considerably, the total amount of their imports of our produce and manufactures.

If imperialism was a loss-making activity – why did Britain and other European colonial empires engage in it for so long?

Smith and Cobden explained it in terms of clientele politics (or Public Choice Economics, as we would say today). Somebody obviously benefited, even if the nation as a whole did not. And the beneficiaries were politically better organised than those who footed the bill.

This proto-Public Choice case against imperialism was not limited to political liberals. Otto von Bismarck, the Minister President of Prussia and future Chancellor of the German Empire, hated liberals in the Smith-Cobden tradition, but he rejected colonialism in terms that almost make him sound like one of them:

The supposed benefits of colonies for the trade and industry of the mother country are, for the most part, illusory. The costs involved in founding, supporting and especially maintaining colonies […] very often exceed the benefits that the mother country derives from them, quite apart from the fact that it is difficult to justify imposing a considerable tax burden on the whole nation for the benefit of individual branches of trade and industry [translation mine].

In his writing about the economics of imperialism, even Michael Parenti, a Marxist-Leninist political scientist (who is, for obvious reasons, popular among Twitter hipsters), sounds almost like a Public Choice economist:

[E]mpires are not losing propositions for everyone. […] [T]he people who reap the benefits are not the same ones who foot the bill. […]

The transnationals monopolize the private returns of empire while carrying little, if any, of the public cost. The expenditures needed […] are paid […] by the taxpayers.

So it was with the British empire in India, the costs of which […] far exceeded what came back into the British treasury. […]

[T]here is nothing irrational about spending three dollars of public money to protect one dollar of private investment – at least not from the perspective of the investors.”

This leads us to a curious situation. Today’s woke progressives disagree with their comrade Parenti on the economics of empire, but they do agree with Britain’s old imperialists, who argued that the Empire was vital for Britain’s prosperity.

August 29, 2023

The noble reasons New Jersey banned self-service gas stations

Of course, by “noble reasons” I mean “corrupt crony capitalist reasons“:

“Model A Ford in front of Gilmore’s historic Shell gas station” by Corvair Owner is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

New Jersey’s law, like Oregon’s, ostensibly stemmed from safety concerns. In 1949, the state passed the Retail Gasoline Dispensing Safety Act and Regulations, a law that was updated in 2016, which cited “fire hazards directly associated with dispensing fuel” as justification for its ban.

If the idea that Americans and filling stations would be bursting into flames without state officials protecting us from pumping gas sounds silly to you, it should. In fact, safety was not the actual reason for New Jersey’s ban (any more than Oregon’s ban was, though the state cited “increased risk of crime and the increased risk of personal injury resulting from slipping on slick surfaces” as justification).

To understand the actual reason states banned filling stations, look to the life of Irving Reingold (1921-2017), a maverick entrepreneur and workaholic who liked to fly his collection of vintage World War II planes in his spare time. Reingold created a gasoline crisis in the Garden State, in the words of New Jersey writer Paul Mulshine, “by doing something gas station owners hated: He lowered prices”.

In the late 1940s, gasoline was selling for about 22 cents a gallon in New Jersey. Reingold figured out a way to undercut the local gasoline station owners who had entered into a “gentlemen’s agreement” to maintain the current price. He’d allow customers to pump gas themselves.

“Reingold decided to offer the consumer a choice by opening up a 24-pump gas station on Route 17 in Hackensack,” writes Mulshine. “He offered gas at 18.9 cents a gallon. The only requirement was that drivers pump it themselves. They didn’t mind. They lined up for blocks.”

Consumers loved this bit of creative destruction introduced by Reingold. His competition was less thrilled. They decided to stop him — by shooting up his gas station. Reingold responded by installing bulletproof glass.

“So the retailers looked for a softer target — the Statehouse,” Mulshine writes. “The Gasoline Retailers Association prevailed upon its pals in the Legislature to push through a bill banning self-serve gas. The pretext was safety …”

The true purpose of New Jersey’s law had nothing to do with safety or “the common good”. It was old-fashioned cronyism, protectionism via the age-old bootleggers and Baptists grift.

Politicians helped the Gasoline Retailers Association drive Reingold out of business. He and consumers are the losers of the story, yet it remains a wonderful case study in public choice theory economics.

The economist James M. Buchanan received a Nobel Prize for his pioneering work that demonstrated a simple idea: Public officials tend to arrive at decisions based on self-interest and incentives, just like everyone else.

QotD: Private versus public decision-making

Those who wish to turn ever-more decision-making power over to government – and, hence, to take such power from individuals operating in their private spheres (including, but not limited to, private markets) – believe this bizarre notion: when Jones has the power to spend Smith’s money and to order Smith about, Smith’s welfare is improved compared to when the power to spend Smith’s money and to determine how Smith will act is reserved to Smith, with Jones’s authority confined to his – Jones’s – own business.

In private-property markets each individual has the power to say “no”, and when each individual says “yes”, that individual spends only his or her own money. Also, in private-property markets each individual’s choices are significant: if Smith chooses to buy a new car, Smith gets the new car that he chooses; if Smith chooses not to buy a new car, Smith gets no new car.

These basic features of private-property markets, along with a handful of other features that are embodied in the common law, ensure not that markets operate “perfectly”, but that the market process is always in action to generally improve the operation and outcomes of markets.

The political marketplace is nearly the exact opposite. In the political marketplace, Jones spends Smith’s money, and Smith has no real power to say no. Nor [are] Smith’s choices ever genuinely significant (unless, of course, Smith becomes one of the relatively small percentage of people who succeed in grabbing hold of political power).

If a malevolent all-powerful being were intent on designing a market that is destined to abuse the vast bulk of people, that devil could do no better than to impose on his victims majoritarian politics largely unconstrained by constitutional rules. This devil – being, of course, ill-mannered, and evilly-intentioned – would seek to destroy private-property markets.

Don Boudreaux, “Bonus Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2019-07-31.

February 6, 2023

Food prices going up? Destroying “excess” production? That’s Canada’s Supply Management system working at peak efficiency!

Jon Miltimore reports on recent comments about some of the weird requirements for quota-holding dairy farmers under the Canadian Supply Management system:

Canadian dairy farmer is speaking out after being forced to dump thousands of liters of milk after exceeding the government’s production quota.

In a video shared on TikTok by Travis Huigen, Ontario dairy farmer Jerry Huigen says he’s heartbroken to dump 30,000 liters of milk amid surging dairy prices.

“Right now we are over our quotum, um, it’s regulated by the government and by the DFO (Dairy Farmers of Ontario)”, says Huigen, as he stands beside a machine spewing fresh milk into a drain. “Look at this milk running away. Cause it’s the end of the month. I dump thirty thousand liters of milk, and it breaks my heart.”

Huigen says people ask him why milk prices are so high.

“This here Canadian milk is seven dollars a liter. When I go for my haircut people say, ‘Wow, seven dollars Jerry, for a little bit of milk'”, he says, as he fills a glass of the milk being dumped and drinks. “I say well, you have to go higher up. Cause we have no say anymore, as a dairy farmer on our own farm. They make us dump it.”

[…]

In the United States, the primary regulations are high-level price-fixing, bans on selling unpasteurized milk (which means farmers have to dump their product if dairy processors don’t buy it), and “price gouging” laws that prevent retailers from increasing prices when demand is low, which incentivizes hoarding.

In Canada, the regulations are even worse.

While the price-fixing scheme for milk in the US is incredibly complicated and leaves much to be desired — there’s an old industry adage that says “only five people in the world know how milk is priced in the US and four of them are dead” — in Canada the price is determined by a single bureaucracy: the Canadian Dairy Commission.

The Ottawa-based commission (technically a “Government of Canada Crown Corporation”), which oversees Canada’s entire dairy system (known as Supply Management), raised prices three times in 2022, citing “the rising cost of production”.

Food price inflation remains a serious issue in Canada, but the problem is particularly acute in regards to dairy products, which has seen their annual inflation rate triple over the past year, to almost 12 percent.

If the farmers were doing this sort of price-fixing themselves, it would be illegal. Instead, because it’s the government doing it, it’s mandatory. You aren’t allowed to produce any of the supply-managed products outside the system, and the government helpfully protects Canadians from being “victimized” by cheaper imports by high tariffs on anything competing with supply managed output.

As with any rigged market, the costs of “protecting” the market are diffused among all Canadian consumers, but the benefits are concentrated in the hands of the quota-holders (and the bureaucrats who oversee the system). My issues with the supply management system are one of the “hobby horses” I’ve ridden many times over my nearly 20 years of blogging.

June 25, 2022

The Public Choice Model in … grand strategy?

One of the readers of Scott Alexander’s Astral Codex Ten has contributed a review of Public Choice Theory and the Illusion of Grand Strategy by Richard Hanania. This is one of perhaps a dozen or so anonymous reviews that Scott publishes every year with the readers voting for the best review and the names of the contributors withheld until after the voting is finished:

[In Public Choice Theory And The Illusion Of Grand Strategy], Richard Hanania details how a public choice model (imported from public choice theory in economics) can explain the United States’ incoherent foreign policy much better than the unitary actor model (imported from rational choice theory in economics) that underlies the illusion of American grand strategy in international relations (IR), in particular the dominant school of realism. As the subtitle “How Generals, Weapons Manufacturers, and Foreign Governments Shape American Foreign Policy” suggests, American foreign policy is driven by special interest groups, which results in millions of deaths for no good reason.

In the unitary actor model, the primary unit of analysis of inter-state relations is the state as a monolithic agent capable of making rational decisions (forming coherent, long-term “grand strategy”) from cost-benefit analysis based on preference ranking and expected “national interest” maximisation.

In the public choice model, small special-interest groups that reap a large proportion of the benefits from a policy (concentrated interests) are much more incentivised to lobby for a policy than the general public who pay for a negligible portion of the cost of the policy (diffused interests) are incentivised to lobby against. The former can coordinate much easier than the latter that has to overcome rational ignorance (the cost of educating oneself about foreign policy outweighs any benefit an one can expect to gain as individual citizens cannot affect foreign policy) and the society-wide collective action problem (irrational for every citizen to cooperate in the prisoner’s dilemma especially if individual gain is negligible) resulting in inefficient (not-public-good-maximising) policymaking i.e. government failure.

And more specifically on the use of Public Choice Theory:

Public choice theory was developed to understand domestic politics, but Hanania argues that public choice is actually even more useful in understanding foreign policy.

First, national defence is “the quintessential public good” in that the taxpayers who pay for “national security” compose a diffuse interest group, while those who profit from it form concentrated interests. This calls into question the assumption that American national security is directly proportional to its military spending (America spends more on defence than most of the rest of the world combined).

Second, the public is ignorant of foreign affairs, so those who control the flow of information have excess influence. Even politicians and bureaucrats are ignorant, for example most(!) counterterrorism officials — the chief of the FBI’s national security branch and a seven-term congressman then serving as the vice chairman of a House intelligence subcommittee, did not know the difference between Sunnis and Shiites. The same favoured interests exert influence at all levels of society, including at the top, for example intelligence agencies are discounted if they contradict what leaders think they know through personal contacts and publicly available material, as was the case in the run-up to the Iraq War.

Third, unlike policy areas like education, it is legitimate for governments to declare certain foreign affairs information to be classified i.e. the public has no right to know. Top officials leaking classified information to the press is normal practice, so they can be extremely selective in manipulating public knowledge.

Fourth, it’s difficult to know who possesses genuine expertise, so foreign policy discourse is prone to capture by special interests. History runs only once — the cause and effect in foreign policy are hard to generalise into measurable forecasts; as demonstrated by Tetlock’s superforecasters, geopolitical experts are worse than informed laymen at predicting world events. Unlike those who have fought the tobacco companies that denied the harms of smoking, or oil companies that denied global warming, the opponents of interventionists may never be able to muster evidence clear enough to win against those in power with special interests backing.

Hanania’s special interest groups are the usual suspects: government contractors (weapons manufacturers [1]), the national security establishment (the Pentagon [2]), and foreign governments [3] (not limited to electoral intervention).

What doesn’t have comparable influence is business interests as argued by IR theorists. Unlike weapons manufacturers, other business interests have to overcome the collective action problem, especially when some businesses benefit from protectionism. By interfering in a foreign state, the US may build a stable capitalist system propitious for multinationals, but can conversely cause a greater degree of instability and make it impossible to do business there; when business interests are unsure what the impact of a foreign policy will be for their bottom line, they should be more likely to focus their lobbying efforts elsewhere.

January 4, 2022

J.K. Rowling’s subversive tale of a government “controlled by and for the benefit of the self-interested bureaucrat”

No, it’s not a new work by Rowling … it’s a deeply embedded thread of her best-known books in the Harry Potter series (as related in a 2005 article by Benjamin H. Barton for the Michigan Law Review):

This Essay examines what the Harry Potter series (and particularly the most recent book, The Half-Blood Prince) tells us about government and bureaucracy. There are two short answers. The first is that Rowling presents a government (The Ministry of Magic) that is 100% bureaucracy. There is no discernable executive or legislative branch, and no elections. There is a modified judicial function, but it appears to be completely dominated by the bureaucracy, and certainly does not serve as an independent check on governmental excess.

Second, government is controlled by and for the benefit of the self-interested bureaucrat. The most cold-blooded public choice theorist could not present a bleaker portrait of a government captured by special interests and motivated solely by a desire to increase bureaucratic power and influence. Consider this partial list of government activities: a) torturing children for lying; b) utilizing a prison designed and staffed specifically to suck all life and hope out of the inmates; c) placing citizens in that prison without a hearing; d) allows the death penalty without a trial; e) allowing the powerful, rich or famous to control policy and practice; f) selective prosecution (the powerful go unpunished and the unpopular face trumped-up charges); g) conducting criminal trials without independent defense counsel; h) using truth serum to force confessions; i) maintaining constant surveillance over all citizens; j) allowing no elections whatsoever and no democratic lawmaking process; k) controlling the press.

This partial list of activities brings home just how bleak Rowling’s portrait of government is. The critique is even more devastating because the governmental actors and actions in the book look and feel so authentic and familiar. Cornelius Fudge, the original Minister of Magic, perfectly fits our notion of a bumbling politician just trying to hang onto his job. Delores Umbridge is the classic small-minded bureaucrat who only cares about rules, discipline, and her own power. Rufus Scrimgeour is a George Bush-like war leader, inspiring confidence through his steely resolve. The Ministry itself is made up of various sub-ministries with goofy names (e.g., The Goblin Liaison Office or the Ludicrous Patents Office) enforcing silly sounding regulations (e.g., The Decree for the Treatment of Non-Wizard Part-Humans or The Decree for the Reasonable Restriction of Underage Sorcery). These descriptions of government jibe with our own sarcastic views of bureaucracy and bureaucrats: bureaucrats tend to be amusing characters that propagate and enforce laws of limited utility with unwieldy names. When you combine the light-hearted satire with the above list of government activities, however, Rowling’s critique of government becomes substantially darker and more powerful. Furthermore, Rowling eliminates many of the progressive defenses of bureaucracy. The most obvious omission is the elimination of the democratic defense. The first line of attack against public choice theory is always that bureaucrats must answer to elected officials, who must in turn answer to the voters. Rowling eliminates this defense by presenting a wholly unelected government.

H/T to Glenn “Instapundit” Reynolds for the link.

February 1, 2021

In the wake of l’affaire GameStop, frantic regulators call for more power to intervene in the market

“Regulatory capture” is the term for situations where the regulators and the regulated begin to get too close and the regulated industries or organizations begin to indirectly control the actions of the regulator for their own benefit. A topical example would be the sudden, agonized cries of politicians and market regulators for new powers to clamp down on disruptive players like the Redditors or other small investors who triggered the rise in GameStop share prices causing potentially ruinous financial losses for regulated hedge funds.

“GameStop” by JeepersMedia is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Although the story has garnered the attention of regulators and even the White House, the wrong takeaway is to suggest options for retail investors should be restricted more than they already are. Yet this is precisely what William Gavin, Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, has called for. Gavin argued that there should be a 30-day trading suspension on GameStop to protect “small and unsophisticated investors.”

Gavin’s suggestion would have serious extended consequences. First, consider the knowledge problem that is involved in constructing such a restrictive regulation. When exactly would a rally become unacceptable? Despite years of decline, Kodak experienced a rally after its announcement that it would move into pharmaceuticals. Would this be permissible? If so, one could simply point to GameStop’s decision to appoint three new directors in an effort to turn the company around. If this is not enough, regulators must clearly state what identified the investments as unacceptable.

It is unclear if there is a perfect benchmark to distinguish rallies. But without such a measure, the suspension proposal would put every rally at risk of wrongful closure — potentially halting the growth of companies and industries, alike. Worse yet, the fear of missing out on a rising stock may push some investors to rush in with less information than they would otherwise acquire. Even if it is in a traditional rally, an uninformed decision could cause more harm than good.

Yet suppose the knowledge problem is solved and there is a perfect measure in place. Should other protections be put in place? One could make the case for a law against allowing “unsophisticated” gamblers from going to Las Vegas and losing money. And although this may seem like a leap, Gavin himself told Reuters, “This isn’t investing, this is gambling,” when he spoke of the GameStop rally.

The rally has attracted the world’s attention, but it does not require it. Rallies are a normal part of financial market activity. The only difference here is that it was Main Street that pulled one over on Wall Street.

July 18, 2020

QotD: Peace can also be the health of the state

War, we libertarians are fond of telling each other, is the health of the state. Peruse the most recent posting here by our own WW1 historian, Patrick Crozier, to see how we often think about such things. So, what about that increasingly obtrusive and kleptocratic Brazilian state that has been putting itself about lately, stirring up misery and libertarianism? There have been no big wars to make the Brazilian state as healthy as it now is, and especially not recently. What of that?

The story Bruno Nardi told made me think of the book that explains how peace is also the health of the state, namely Mancur Olson’s public choice theory classic, The Rise and Decline of Nations. It is years since I read this, but the story that this book tells is of the slow accumulation and coagulation of politics, at the expense of mere business, as the institutions of a hitherto thriving nation gang up together to form “distributional coalitions” (that phrase I do definitely recall). The point being that if you get involved in a war, and especially if you lose a war, the way Germany and Japan lost WW2, that tends to break up such coalitions.

The last thing on the mind of a German trade unionist or businessman, in 1946, was lobbying the government for regulatory advantages or for subsidies for his particular little slice of the German economy. Such people at that time were more concerned to obtain certificates saying that they weren’t Nazis, a task made trickier by the fact that most of them were Nazis. Olson’s way of thinking makes the post-war (West) German and then Japanese economic miracles, and the relative sluggishness of the British economy at that time, a lot more understandable. Winning a war, as Olson points out, is not nearly so disruptive of those distributional coalitions, in fact it strengthens them, as Crozier’s earlier posting illustrates.

Brian Micklethwait, “The view from Brazil is that peace is also the health of the state”, Samizdata, 2018-04-13.

February 20, 2020

QotD: Preventing bureaucratic mission creep

The mission creep that is the effect of those not slumbering in meetings and thus adding another bright idea to the tasks the organization attempts is not restricted to the public sector.

Private companies are just as vulnerable. However in that private sector we have a mechanism by which the seemingly inevitable bureaucratization is dealt with. Once it happens, the organization goes bankrupt and is removed from the scene. What we need is a similar system to deal with this process in the public sphere.

I don’t, given the above, find it at all remarkable that the WTO is regarded as succumbing to these forces, nor the UN, Amnesty, the European Union or even our own domestic governments (just how did the interstate commerce clause become a justification for Congress to restrict something that is not interstate and is not commerce?). I think it inevitable.

Various solutions appear to be available, the French one might be an example. Put up with it for 50 years then have a revolution and start again. Perhaps the answer is never to allow the public bodies to have much power in the first place, a solution that hasn’t really been tried anywhere. The Italian one? Let the system carry on adding ever more layers but ignore it? Stalin’s? Every 15 years or so shoot the bureaucrats?

All such methods have their attractions and their faults but a solution we do need to find. For one of the lessons I take from the history of the 20th century is that we don’t actually want to be ruled by those who stay awake in committee meetings.

Tim Worstall, “‘Any Organization Will, In the End, Be Run By Those Who Stay Awake in Committee'”, Ideas in Action, 2005-06-23.

October 9, 2017

Reviewing Democracy in Chains as speculative fiction, rather than as history

James Devereaux critiques the recent book by Nancy MacLean which was intended to tarnish the reputation of James McGill Buchanan by tracing the intellectual roots and influences that shaped Buchanan’s life and work.

Nancy MacLean, in her new book Democracy in Chains, has allegedly revealed the master plan of right-wing political operatives, funded by the Kochs and inspired by James McGill Buchanan. MacLean pulls no punches as she describes a right-wing conspiracy meant to bring about “a fifth column movement the likes of which no nation has ever seen.” (page 127) Alas, the major problem with her account, as her fellow Duke Professor Mike Munger summarized, is it is “a work of speculative historical fiction.” MacLean’s contribution is a failure of academic discourse more likely to increase unfounded paranoia and division than to reveal any hidden agenda. MacLean’s bias bleeds into nearly every aspect of this book and taints her interpretation of the facts and sources beyond any reasonable interpretation could support. At one point she ponders the genius of Buchanan but determines it to be an “evil genius” for his work, much of which discusses the difficulties of democracy (page 42).

Why, one may feel justified in asking, dwell on speculative fiction? Unfortunately, when speculative fiction enters the popular culture, is applauded, and treated as fact, a measure of scrutiny is required. MacLean has received a fair share of positive press. NPR wrote that Democracy in Chains is “a book written for the skeptic; MacLean’s dedicated to connecting the dots.” That is if the dots were points on a corkboard tied together with red yarn. Oprah’s book club put it in their “20 books to read this summer” list. The Atlantic’s review praised the book as “part of a new wave of historiography that has been examining the southern roots of modern conservatism.” Slate also wrote a review.

A Deluge of Error

MacLean’s revelation regarding this “stealth plan” for a “fifth column movement” focuses on the relatively obscure, but well-respected, founder of public choice economics Nobel laureate James McGill Buchanan. MacLean weaves a fascinating tale but one that paints Buchanan and sympathizing libertarians as radicals determined to undermine democracy for the purpose of satisfying elitist urges, squashing the underdog, burdening the minority, and exploiting the poor. Unfortunately for MacLean, and those heaping praise, it is clear this tale rests on ransom-note-style citations, cutting and pasting together portions of phrases to change the meaning and support her narrative. In certain places it appears she has woefully misunderstood the source material or did not care – the notes do not match the claims. By cobbling together this mish-mash of selective quotes and speculation MacLean errs twice: first in describing Buchanan’s views and second in describing the motives of Buchanan and anyone sympathetic to his view.

A litany of scholars have examined the book and revealed a deluge of error. Russ Roberts wrote that MacLean owed Tyler Cowen an apology, courteously gave her room to respond, which she used to double down on her claims despite the obvious selective use of unfairly parsed phrases which attributed a view to Cowen he did not hold. Steve Horwitz, Michael Munger, Jonathan Adler, and David Bernstein have found issues with her citations and claims (Adler aggregated them at the Washington Post). Most thoroughly, Phil Magness has dissected numerous errors, misquotes, and general failures of citation found within the book, it appears to be an ongoing project. The errors which have compiled are such that they undermine credibility in the reading. As others have listed her poor citations, mangling of quotes, and selective editing, this will not be the focus of this review.

Since the publication of Maclean’s book, Don Boudreaux at Café Hayek has been hammering her work on an almost daily basis.

July 23, 2017

Canada won’t give up on supply management, for fear of Quebec backlash

Pierre-Guy Veer provides a guided tour of Canada’s supply management system, with appropriate emphasis on the role Quebec dairy producers play in keeping the anti-competitive system in place:

Spared by the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994, the Canadian milk supply restrictions are “in danger” again. Because of trade negotiations with the US and Europe, foreign farmers want better access to the Canadian market.

However, hearing complaints from the US about unfree dairy markets comes as paradoxical. Indeed, since the Great Depression, the dairy industry has been anything but free. It profits from various subsidies programs including “the Dairy Price Support Program, which bought up surplus production at guaranteed prices; the Milk Income Loss Contracts (MILC), which subsidized farmers when prices fall below certain thresholds, and many others.” It even came close to supply management in 2014, according to the Wilson Center.

But nevertheless, should US farmers ever have greater access to Canadian markets, it won’t be without a tough fight from Canadian farmers, especially those from the province of Quebec. Per provincial Agriculture Ministry (MAPAQ) figures, the dairy industry is the most lucrative farm activity, accounting for 28% of all farm revenues in the province, but also 37% of national milk revenues in 2013. “La Belle Province” also has 41% of all milk transformation manufacturers in Canada.

As is almost always the case with “protected” domestic markets, the overall costs to the Canadian economy are large, but the potential benefit to individual Canadian consumers for getting rid of supply management is relatively small (around $300 per year), but the benefits are tightly concentrated on the protected dairy producers and associated businesses.

But even though the near entirety of the population would profit from freer dairy markets, their liberalization will not happen anytime soon.

Basic Public Choice theory teaches that tiny organized minorities (here: milk producers) have so much to gain from making sure that the status quo remains. A region like Montérégie (Montreal’s South Shore) produced over 20% of all gross milk revenues in 2016. There are 23 out of 125 seats in that region, making it the most populous after Montreal (28 seats). So if a politician dares to question their way of living, milk producers will come together to make sure he or she doesn’t get elected. Libertarian-leaning Maxime Bernier learned it the hard way during the Canadian Conservative Party leadership race; producers banded together – some even joined the Conservative Party just for the race – and instead elected friendlier Andrew Scheer.

On the provincial level, all political parties in the National Assembly openly support milk quotas. From the Liberal Party to Coalition Avenir Québec and to Québec Solidaire, no one will openly talk against milk quotas. However, and maybe unwillingly, separatist leader Martine Ouellet gave the very reason why milk quotas are so important: they keep the dairy industry alive.

July 15, 2017

Another critique of Nancy MacLean’s book smearing economist James M. Buchanan

In the Washington Post, a fellow Duke professor airs some concerns over MacLean’s recent character assassination attempt, Democracy in Chains:

Professor Nancy MacLean’s book Democracy in Chains has received considerable attention since its release a few weeks ago. A recent Inside Higher Ed article reports on the critical reviews and Professor MacLean’s allegation that these critiques are part of a coordinated, “right-wing” attack on her work. The book’s central thesis — summarized elegantly in the Inside Higher Ed piece – is that Nobel Prize-winning economist James M. Buchanan “was the architect of a long-term plan to take libertarianism mainstream, raze democratic institutions and keep power in the hands of the wealthy, white few.” MacLean concludes that Buchanan’s academic research program — known as public choice theory — is a (thinly) disguised attempt to achieve this purpose, motivated by racial and class animus.

As president of the Public Choice Society (the academic organization founded by Buchanan and his colleague Gordon Tullock), I am writing to respond to Professor MacLean’s portrayal. Since she believes that critiques of the book are part of a coordinated attack funded by Koch money, let me begin with a disclosure. I have no relationship with the Kochs or the Koch organization. I have never received money from them or their organization, either personally or to support my research. I have not coordinated my response to the book with anyone. I do, however, have a personal connection to Buchanan. My father was a longtime colleague and co-author of Buchanan’s. I am also very familiar with Buchanan’s academic work, which relates directly to my own research interests. In short, I know Buchanan and his work well, but I am certainly not part of the “dark money” network Professor MacLean is concerned about.

There are many things to be said about Professor MacLean’s book. For an intellectual historian, the documentary record constitutes the primary source of evidence that can be offered in support of arguments or interpretations. For this reason, intellectual historians generally apply great care in sifting through this record and presenting it in a way that accurately reflects sources. As numerous scholars have by now shown (see here, and links therein, for an example), Professor MacLean’s book unfortunately falls short of these standards. In many instances, quotations are taken out of context or abbreviated in ways that suggest meanings radically at odds with the tenor of the passage or document from which they were taken. Critically, these misleading quotations are often central to establishing Professor MacLean’s argument.

[…]

What then, of “chains on democracy”? It is true that Buchanan did not think much of unfettered, majoritarian politics and favored constitutional rules that restrict majority rule. But the foregoing discussion should already make clear that this conclusion was not based on an anti-democratic instinct or a desire to preserve the privilege of a few. Instead, Buchanan’s careful analysis, originating in his seminal work with Gordon Tullock, The Calculus of Consent, led him to the conclusion that in choosing a political framework (“constitution”), all individuals will typically have good reasons to favor some restrictions on majority rule in order to protect against the “tyranny of the majority.” As he argued, democracy understood simply as majority rule “may produce consequences desired by no one unless these procedures are limited by constitutional boundaries” (Buchanan 1997/2001: 226). In other words, what justifies “chains on democracy” for Buchanan are his commitment to individual autonomy and equality, and his emphasis on consent as a legitimating principle for political arrangements. To paint his endorsement of constitutional limits on the use of political power as motivated by an anti-democratic desire to institute oligarchical politics is to fundamentally misunderstand Buchanan’s sophisticated, subtle approach to democratic theory, which was committed above all to the idea that political arrangements should redound to the benefit of all members of a community.

July 5, 2017

“[O]dious, hypocritical, and archly anti-capitalistic 19th-century slavery apologist John C. Calhoun is the spirit animal of contemporary libertarianism”

Nick Gillespie on Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America, by Duke historian Nancy MacLean:

This book, virtually every page announces, isn’t simply about the Nobel laureate economist James Buchanan and his “public choice” theory, which holds in part that public-sector actors are bound by the same self-interest and desire to grow their “market share” as private-sector actors are.

No, MacLean is after much-bigger, more-sinister game, documenting what she believes is

the utterly chilling story of the ideological origins of the single most powerful and least understood threat to democracy today: the attempt by the billionaire-backed radical right to undo democratic governance…[and] a stealth bid to reverse-engineer all of America, at both the state and the national levels, back to the political economy and oligarchic governance of midcentury Virginia, minus the segregation.

The billionaires in question, of course, are Koch brothers Charles and David, who have reached a level of villainy in public discourse last rivaled by Sacco and Vanzetti. (David Koch is a trustee of Reason Foundation, the nonprofit that publishes this website; Reason also receives funding from the Charles Koch Foundation.) Along the way, MacLean advances many sub-arguments, such as the notion that the odious, hypocritical, and archly anti-capitalistic 19th-century slavery apologist John C. Calhoun is the spirit animal of contemporary libertarianism. In fact, Buchanan and the rest of us all are nothing less than “Calhoun’s modern understudies.”

Such unconvincing claims (“the Marx of the Master Class,” as Calhoun was dubbed by Richard Hofstadter, was openly hostile to the industrialism, wage labor, and urbanization that James Buchanan took for granted) are hard to keep track of, partly because of all the rhetorical smoke bombs MacLean is constantly lobbing. In a characteristic example, MacLean early on suggests that libertarianism isn’t “merely a social movement” but “the story of something quite different, something never before seen in American history”:

February 6, 2016

The most likely explanation for politicians doing what they do

In his weekly column for USA Today, Glenn Reynolds distills down the essence of public choice theory:

The explanation for why politicians don’t do all sorts of reasonable-sounding things usually boils down to “insufficient opportunities for graft.” And, conversely, the reason why politicians choose to do many of the things that they do is … you guessed it, sufficient opportunities for graft.

That graft may come in the form of bags of cash, or shady real-estate deals, or “consulting” gigs for a brother-in-law or child, but it may also come in broader terms of political support and even in opportunities for politicians to feel superior or to humiliate their enemies. What all these things have in common, though, is that they’re not about making life better for voters. They’re about making life better for politicians.

This doesn’t sound much like the traditional view of politics, as embodied in, say, the Schoolhouse Rock “I’m Just A Bill” video. But it’s a view of politics that explains an awful lot.

And there’s a whole field of economics based on this view, called “Public Choice Economics.” Nobel prize winning economist James Buchanan referred to public choice economics as “politics without romance.” Instead of being selfless civil servants motivated solely by the public good, public choice economics assumes that politicians are, like other human beings, heavily influenced by self-interest.

Public choice economists say that groups don’t make decisions, individuals do. And individuals mostly do what they think will be best for them, not for the “public.” Public choices, thus, are like private choices. You pick a car because it’s the best car for you that you can afford. Politicians pick policies because they’re the best policies — for them — that they can achieve.

How do they get away with this? First, most voters are “rationally ignorant.” That is, they realize that their vote isn’t likely to make much of a difference, so it’s not rational to learn all the ins and outs of policy or of what political leaders are doing. Second, the entire system is designed — by politicians, naturally — to make it harder for voters to keep track of what politicians are doing. The people who have a bigger stake in things — the real estate developers or construction unions — have an incentive to keep track of things, and to influence them, that ordinary voters don’t.

Can we eliminate this problem? Nope. But we can make it worse, or better. The more the government does and the more decisions that are relegated to bureaucrats, “guidance” and other forms of decisionmaking that are far from the public eye, the more freedom politicians have to pursue their own interest at the expense of the public — all while, of course, claiming to do just the opposite. Meanwhile, if we do the opposite — give the government less power and demand more accountability — politicians can get away with less. But they’ll always get away with as much as they can.