The past has always interested me more than the future. This backward-looking tendency has only been reinforced by reaching, somewhat unexpectedly, the age of 70. I can’t say that I don’t feel my age because I don’t know what feeling any particular age is like — but one repeatedly hears that 60 is the new 40, 70 is the new 50, and so on; certainly, the human aging process has slowed since I was born. When I look at photos of people who were 50 in the year of my birth, 1949, they look much older and more worn-out than do 50-year-olds now; and if I had lived only to my life expectancy at birth, I would be dead these last four years.

So progress must have occurred in the intervening time, despite the pessimism that infects those who, like me, are of retrospective temperament and hypersensitive to deterioration. It is not hard to enumerate many things that have improved. They relate principally, but not only, to material conditions. My best friend when I was very young was one of the last children in Britain to suffer from polio, which paralyzed him from the waist down. The quickest form of written communication was then the telegram, and anything other than local telephone calls had to go through an operator. To call across the Atlantic required a reservation and was ferociously expensive; the resultant conversation always seemed to take place during a violent storm. In England, the food was generally disgusting, and meals were to be endured as a regrettable necessity instead of enjoyed (it puzzles me still how people could have cooked so badly). Cars broke down frequently, and every November, pollution produced fogs so thick that you couldn’t see the hand in front of your face (I loved them). Rationing continued for eight years after the war, and disused bomb shelters, present in every park, were where illicit sexual fumbles and smoking took place. Incidentally, for an adult male not to smoke was unusual (75 percent did so); we must have lived in a perpetual fog of foul-smelling tobacco, to judge by the distaste caused by even a single lit cigarette in these virtuous times. Poverty, as raw necessity, still existed. Murderers were sometimes hanged — as well as, more rarely, the innocent. Overt racial prejudice was, if not quite the norm, certainly prevalent.

Yet not everything has improved, though the deterioration has been less tangible than the progress. To give one example: by age 11, I was free to roam London, or at least its better areas, by myself or with a friend of the same age. The sight of an 11-year-old child wandering the city on his own did not suggest to anyone that he was neglected or abused. I remember, too, the evening papers piled up at newsstands; people would throw coins on top of the pile and take their copy. It never occurred to anyone that the money might get stolen; nowadays, it would never occur to anyone that the money would not be stolen. The crime statistics bear out this sea change in national character.

Theodore Dalrymple, “What Seventy Years Have Wrought”, New English Review, 2019-10-26.

June 25, 2024

QotD: Progress and decline

January 20, 2024

QotD: 19th Century techno-optimism

In The Politics of Cultural Despair (a book I recommend, with reservations), Fritz Stern called the writers of the 19th century “conservative revolution” in Germany “intellectual Luddites”. Just as the original Luddites wanted to stop “progress” by breaking machines, so the intellectual Luddites wanted to un-enlighten the Enlightenment, wiping out “Manchesterism” to return to a largely imaginary communitarian, agrarian past. The “machine” the intellectual Luddites sought to break, Stern argues, was reason … or, at least, rationalism, which by the later 19th century was basically the same thing in most people’s minds.

They had a point, those intellectual Luddites. If you haven’t read up on the later 19th century in a while, it’s almost impossible to convey their boundless optimism, their total faith that “science” could, would, and should solve every conceivable problem. The best I can do is this: Back when they were still allowed to be funny, The Onion published a book called Our Dumb Century, which purported to be a collection of their front pages from every year of the 20th century. The headline for 1903 was something like: “Wright Brothers’ Flyer Goes Airborne for 30 Seconds! Conquest of Heaven Planned for 1910.”

That’s the late 19th century, y’all.

Severian, “Digital Infants”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-04-16.

February 13, 2023

Appliance futility by design

Tal Bachman recounts a miserable — but increasingly common — experience with modern “energy efficient” home appliances:

“A-rated energy appliances” by Tom Raftery is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The LG 5.8 cubic foot Capacity Top Load Washer sat in the laundry room, brand new. Maybe it was my imagination, but it looked insouciant.

Dad said it was the latest and greatest in laundering technology. Supposedly, some sort of internal sensor system (having something to do with a computer) fine-tuned water levels depending on clothing weight. Or something. I can’t remember exactly what he — or was it the moving guy? — said.

I did notice the washing machine had several preset wash cycles — Allergiene, Sanitary, Bright Whites, Towels, Heavy Duty, Bedding, and more. You could select them with a shiny, space-age-looking chrome dial. (I would later discover the machine had other fancy features with names like TurboWash™ 360, ENERGY STAR® Qualified, Smart Diagnosis™, and ThinQ™ Technology [Wi-Fi Enabled]).

[…]

Well, it was win-win-win, with a minor caveat. The caveat was the washing machine. Turns out that for all its razzle-dazzle features, it didn’t actually clean clothes. Even worse, it took hours to not clean clothes. The “Allergiene” cycle, for example, took almost four hours. Yet when you pulled your clothes out, you could still make out the orange juice or tomato sauce stains. I’d never encountered a more useless washing machine.

“How you feeling about this new washing machine?”, I asked Dad, a few days after the hunkering down began.

“Great!”, said Dad.Okay, I thought. That’s not unusual. Music — as opposed to the mundane or practical — occupies most of Dad’s awareness, and always has. Besides, most of his clothes are black, and he probably hasn’t noticed it’s not removing the ketchup stains. Maybe he will in a few weeks.

And maybe in the meantime, I thought, I could figure out a way to reprogram the machine for cycles which actually washed. And were faster.

But no. That turned out to be way too much to hope for. The machine allowed no independent control over water volume, cycle time, or water temperatures. It only allowed selection of a preset computerized cycle — none of which got your clothes clean.

[…]

Yet more irritating was the reason it skimped on water and power: it was trying to stop global warming. Oops — I mean “climate change”. It was “environmentally friendly”. Except it wasn’t, because you usually had to run at least two cycles to get your clothes clean. That’s right: you had to use the same amount of water in the end anyway, and double the electricity.

And so — not for the first time — I had stumbled upon yet another example of technological “progress” which exacerbated the very (pseudo) problem it purported to solve. The new useless LG “Save the World!” piece of garbage was the home equivalent of Hollywood stars taking private jets to a carbon reduction conference in Switzerland.

[…]

The US Department of Energy, I discovered, had begun imposing energy efficiency regulations in the early 1990s. A decade later, they made the regulations even stricter (see here also). Then, as the years passed, they made them even stricter. And then stricter. And then stricter. All the while, the feds offered appliance manufacturers huge tax incentives — i.e., huge cash rewards — to accelerate their phase out of functional washing machines.

Government succeeded. Today, minus the loophole-exploiting Speed-King (which the feds will probably crush soon), you cannot find a new washing machine — front- or top-loading — which washes clothes anywhere near as well as its predecessors. The rationale for this — saving the world from global warming — doesn’t even rise to the level of ludicrous. Just for starters, as I type this, we’re enduring one of the coldest winters ever recorded. New Hampshire’s Mount Washington Observatory just recorded a wind chill calculation of minus 109 degrees Farenheit, an all-time record for the United States (and approaching midway between the average temperatures of Jupiter and Mars). Temperatures are thirty degrees Farenheit colder than average in many places. Why would anyone want to bring temperatures down even further? And at the cost of destroying washing machine functionality? And what loon could actually believe home washing machines change the climate?

In any case, thanks to an essentially totalitarian government run by bought-and-paid-for liars, control freaks, and imbeciles, we have gone technologically backward — certainly in the appliance domain, but in others — for no good reason at all. (Regulations have also downgraded dishwashers, toilets, showers, and other appliances, but we can discuss those another time)

Back in 2019, Sarah Hoyt expressed her frustrations with “modern” “energy-efficient” appliances which matched our experiences exactly.

January 16, 2023

QotD: The avant-garde

There is no more evanescent quality than modernity, a rather obvious or even banal observation whose import those who take pride in their own modernity nevertheless contrive to ignore. Having reached the pinnacle of human achievement by living in the present rather than in the past, they assume that nothing will change after them; and they also assume that the latest is the best. It is difficult to think of a shallower outlook.

Of course, in certain fields the latest is inclined to be best. For example, no one would wish to be treated surgically using the methods of Sir Astley Cooper: but if we want modern treatment, it is not because it is modern but because it better as gauged by pretty obvious criteria. If it were worse (as very occasionally it is), we should not want it, however modern it were.

Alas, the idea of progress has infected important spheres in which it has no proper application, particularly the arts. It is difficult to overestimate the damage that the gimcrack notion of teleology inhering in artistic endeavour has inflicted on all the arts, exemplified by the use of the term avant-garde: as if artists were, or ought to be, soldiers marching in unison to a predetermined destination. If I had the power to expunge a single expression from the vocabulary art criticism, it would be avant-garde.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Architectural Dystopia: A Book Review”, New English Review, 2018-10-04.

May 23, 2021

Peter Zeihan’s geographic-based perspective on world history

In another of the reader-contributed book reviews for Scott Alexander’s Astral Codex Ten, a look at The Accidental Superpower: The Next Generation of American Preeminence and the Coming Global Disorder by Peter Zeihan:

Zeihan’s primary models are influenced by his geographic-based perspective on how our world works. As he puts it in the introduction, “Geopolitics is the study of how place [rivers, mountains, etc.] impacts … everything.” Early chapters discuss what he calls the balance of transport, which is roughly easy transport within a country (for economic development and forming political and cultural ties) and hard transport from outside of it (for defense). These transport issues are inherently tied to geography. What’s the best way to move things? Water-based transportation is extremely cheap. Think 17 cents per container mile vs. $2.40 for semis on an American highway, with a more extreme disparity for other countries, trade between continents, and populations in hard-to-access places. On the defensive side of that equation, geographic features on borders such as deserts, mountains, and oceans get Zeihan’s attention.

He uses ancient Egypt to illustrate a great balance of transport. The reliable water and rich soil of the Nile’s floodplains created near-perfect farming conditions, and the Nile itself allowed easy travel and trade throughout the valley. Combined with impenetrable desert borders, this geography “was one of the few places in the world where there was enough water to survive, and enough security to thrive.” Because of that, the “geography nearly guaranteed that the Egyptians would be on the road to civilization.” He gives us a quick run through Egyptian history to tell a story of that road, beginning with the settlement of the area about eight thousand years ago, consolidation into a single kingdom more than five thousand years ago, and then stagnation as the increasingly centralized government devoted more labor to monument building rather than technological progress, eventually being conquered by seafaring people seeking to rule the Mediterranean.

*****

To escape our pre-civilization/hunter-gatherer days – Zeihan refers to this as “when life sucked” – the mechanism that he identifies is basically a typical economist’s story. Sedentary agriculture as invented by the Egyptians and other ancient cultures became a transformative technology, letting populations grow and devote labor and resources to non-farming purposes. From this, we got specialization, increased production, trade (particularly where there was easy transportation – population centers were always near water) and capital formation in a self-reinforcing cycle. For thousands of years after this transformative technology was introduced, incremental improvements in agriculture and other areas followed, but “a robust, secure, and sustainable food supply” was the base of any civilization.

This cycle accelerated when we harnessed a couple of new packages of technologies over the last six-hundred years. He lumps the source of much progress together with the terms deepwater navigation and industrialization. The first is everything needed to sail the seas, from shipbuilding capabilities to compasses to weapons. Industrialization is exactly what you’re thinking of. He simplifies it as the combination of labor and capital with higher-output energy sources like oil and coal to put productivity on steroids.

Zeihan gives us a story of the Ottoman Empire entering a prolonged decline as deepwater navigation technologies took off in the fourteenth century. These technologies enabled the European powers (first Portugal and Spain, and then England) to capture increasing shares of trade with Asia, dropping prices in Europe and depriving the Ottomans of much of the income to which they had grown accustomed. Most significantly, they turned “the ocean from a death sentence to a sort of giant river.” Trade became global, but it was still mostly among people with nearby water-based transportation.

Industrialization technologies changed that. Steam and coal brought power to mining and transportation, and along with interchangeable parts, improved manufacturing. Chemical breakthroughs led to fertilizers (improving crop yields), and with more transportation options, more land was brought into cultivation. Improvements in cements in the 1820s enabled larger buildings and infrastructure. These technologies continually improved the productivity cycle that began with agriculture.

Zeihan concludes a chapter on America with the “nuts and bolts” of how countries rule the world. “The balance of transport determines wealth and security. Deepwater navigation determines reach. Industrialization determines economic muscle tone. And the three combined shape everything from exposure to durability to economic cycles to outlook.” As we’ll see shortly, he really likes America’s position on all of these factors. But first, we need to understand the other analytical tool that informs Zeihan’s model.

January 1, 2021

The paradox of innovation – the more you have, the less impact each individual innovation has

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the oddity that as the British economy expanded during the early Industrial Revolution, each new discovery had less and less direct impact on the economy as a whole:

What this means is that when there were even some slight improvements in agriculture alone, the effects on living standards could be dramatic. But absent such improvements, a rich culture of innovation affecting everything from clothes to watches to books, wine, glassware, metals, and pottery would have been almost entirely masked from the figures. Importantly, the same applies not only to the composition of average notional consumption baskets, but to the contributions of different sectors to the economy as a whole. While the total amount of food has increased dramatically for the past few hundred years, for example, agriculture’s share of the economy steadily fell (from over 40% of the English economy in 1600, and an even greater share of total employment, to less than 1% today, with a similar trend repeated worldwide). So the relative importance of your typical agricultural innovation for overall growth rates has fallen dramatically. Perhaps it’s no wonder that twentieth-century agricultural pioneers like Norman Borlaug still don’t really get their due.

The same goes, more recently, for manufacturing. The reason the textbooks always name Kay, Hargreaves, Crompton, Cartwright and Arkwright, is because they made improvements to what was already one of the most important sectors of the economy: textiles. In the eighteenth century, textiles as a whole accounted for a whopping 16-17% of the British economy. So any growth in the value of wool, linen, and increasingly cotton goods, had an appreciable impact on overall economic growth. Today, by contrast, you’d be hard pressed to find many sectors that account for even 5% of the country’s economy (except construction, and possibly financial services, depending on how broadly you define them). And while Britain may have long lost its role as the workshop of the world, textile production in China today still only accounts for about 7% of the country’s economy. To put it another way, the modern Arkwrights and Cartwrights and Cromptons of China, to have any comparable effect on national statistics, would have to make productivity improvements to their industry that are at least three times as impressive.

And impressive they are, though you won’t have heard of them. Arkwright and Crompton multiplied the number of threads that a single machine could spin, from one to dozens. Today, thread is spun by the thousands, at speeds they could have scarcely comprehended, and with entire factories hardly needing a single pair of human hands. Automatic sensors monitor the yarn’s tension and detect any defects while it is being spun, with robots even whizzing along to repair any snaps, able to find a loose end and piece the yarn together again — a task that once required the nimble fingers of small children. From an eighteenth-century perspective, our textile machines routinely now do magic, and are getting ever more fantastical every day. Imagine showing Arkwright the use of lasers in fading and cutting jeans.

But by replacing human labour, innovation has become ever more hidden. Many people don’t realise that British manufacturing is actually larger and more valuable than ever. It’s just that it employs fewer people than ever, so hardly anybody gets to witness its great strides forwards (to witness a flavour of manufacturing’s modern marvels, I recommend checking out MachinePix).

And more importantly, the overall effect of each innovation has also been steadily diluted — itself the result of growth. Innovation has, in a sense, been the victim of its own success. By creating ever more products, sprouting new industries, and diversifying them into myriad specialisms, we have shrunk the impact that any single improvement can have. When cotton was king, a handful of inventors might hope to affect the entire national textile industry in some way. Nowadays, there’s not a chance. Doubling the productivity of cotton spinning is all well and good, but what about nylon, polyester, rayon, and the host of other fibres we have since invented? And which kind of spinning machine would you improve? An old-fashioned ring-spinner, a newer rotor spinner, or perhaps even one of the brand new air-jet types?

If you make an improvement, it’s not going to be to the industry as a whole — it’ll be specific. And actually improvements have always been specific; it’s just that the industries have since multiplied and narrowed. Inventors once made drops into a puddle, but the puddle then expanded into an ocean. It doesn’t make the drops any less innovative. This paradox of progress affects all innovation, such that it is no wonder that the number of researchers has been increasing while national-level productivity growth has appeared fairly stagnant. Even general-purpose technologies, like the recent dramatic improvements to telecommunications, computing, and software, have had a muted effect, being applied more slowly than we’d have liked. I expect that all future general-purpose technologies will fare even worse, for it takes still further effort and innovation to apply a technology to a given industry, and those industries will continue to multiply. All future general-purpose technologies, that is, except improvements to energy.

November 26, 2020

QotD: The “history-as-nightmare” narrative

The idea of the past as nothing but a nightmare, specifically one of injustice, is probably the prevailing historiographical trope of our time. Certainly no one could reasonably claim that nightmares have been lacking in human history. And yet, at the same time, it is undeniable that there has been progress: very few of us would care to take our chances in the kind of conditions, either political or material, that prevailed in, say, the 16th century.

The fact remains, however, that for more than one reason, history-as-nightmare is nowadays an infinitely more powerful organising narrative principle than history-as-progress.

In the first place, nightmares present themselves much more vividly to the imagination than the slow accretion of progress, just as hell is much more easily envisaged than heaven — and more enjoyable to imagine, too.

In the second place, when progress occurs, it is immediately taken for granted, as if it were a merely natural process that had never really required human effort to take place. Who now is grateful for the elimination of the suffering caused by peptic ulceration, for example? There is simply no cultural recollection of peptic ulceration at all, though well within living memory books were written about how to live with, or despite, your ulcer, what diet to take to assuage your ulcer, and so forth. Once they are cured, it is simply taken for granted that people do not have such maladies — progress magically did away with them.

In the third place, and most importantly, the fact of progress is much less useful to political entrepreneurs than is the narrative of history as nothing but a nightmare that continues to the present day and, as Marx put it, weighs upon the brain of the living. Only by keeping the memory of the nightmare ever-present in the minds of their sheep, thereby stoking resentment, may the political shepherds herd, and then fleece, the flock.

A fourth great advantage of history-as-nightmare is that it explains the failures and failings of everybody who is dissatisfied or disappointed with his life. To misquote Shakespeare: The fault, dear Brutus, is not in ourselves, but in our stars, that we are underlings. We do not fail the world, the world fails us. How comforting a thought!

Theodore Dalrymple, “Against History-as-Nightmare”, Law & Liberty, 2020-08-11.

September 7, 2020

QotD: H.L. Mencken on progress

Progress, then, as I see it, is to be measured by the accuracy of man’s knowledge of nature’s forces. If you examine this sentence carefully you will observe that I conceive progress as a sort of process of disillusion. Man gets ahead, in other words, by discarding the theory of to-day for the fact of to-morrow. Moses believed that the earth was flat, Caesar believed that his family doctor could cure pneumonia, and Columbus believed that devils entered into harmless old women and turned them into witches … You and I, knowing that all three of these distinguished men were wrong in their beliefs, are their superiors to that extent.

H.L. Mencken, Men versus the Man: A Correspondence between Robert Rives La Monte, Socialist, and H.L. Mencken, Individualist, 1910.

August 11, 2020

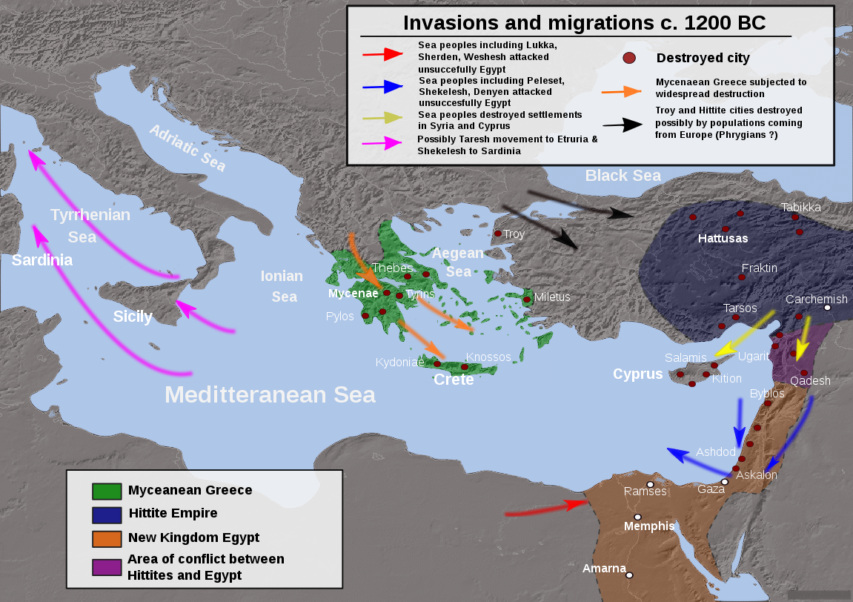

David Warren offers an unusually contrarian view of the Bronze Age collapse

Sea Peoples? Faugh, Mr. Warren isn’t buying any of that old rope. It wasn’t earthquakes, famine, plagues, or even multiple waves of heavily armed undocumented immigrants landing on the shores … it was mere “progress”:

Migrations, invasions and destructions during the end of the Bronze Age (c. 1200 BC), based on public domain information from DEMIS Mapserver.

Map by Alexikoua via Wikimedia Commons.

When did the Bronze Age end, and the Iron Age begin? The ages of plastic, silicon, and graphene may have succeeded even the latter, but I’m still not comfortable with iron. Neither were the Cypriots, nor the Egyptians, incidentally — some thirty-something centuries back. Before even that, iron was freely available in a globalized world. I once took a modified fishing boat from Cyprus to Mersin; I wouldn’t encourage swimming it. But the voyage is not far, and too quick with a motor. Even in a row boat, it would have been easy to smuggle ferrous materials, either way.

Yet for centuries, such “highly sophisticated” societies as those of Cyprus and Egypt, stuck with copper and bronze; with gold and silver adornments. The rest of the world might have been with the progressive agenda, but they were not. I speculate that they didn’t like the way iron rusts; there’s something cheap about it. But whatever the objection, they stood their ground. There are old iron objects to be found in both places, but few.

Much later, when the “lifestyle” advocates for the new fashionable metal had won out, and the tide of iron was flooding, it is interesting that the craftsmanship of objects is relaxed. Even ceramics become dull, boring, repetitious; skills are forgotten. We have craftsmen who obviously don’t give a damn any more, just like today. We have the encroaching realm of “productivity,” quantity. Soon these places are easy to knock over, by the conquering savages always lurking about.

We have conservative societies, overwhelmed by technology; and no longer trading on their own terms. In the larger Minoan sphere, we have barbarization. Dynastic Egypt will survive only in Coptic fragments. Greeks, Romans, and finally Arabs will be trashing the place. Ancient civilizations fall.

I regret “progress.” We should resist it heart and soul.

July 9, 2019

“Why can’t America have great trains?”

At the very end of his recent book Romance of the Rails, Randal O’Toole regretfully (he really, genuinely is a train fan) answers the question three ways … none of which bolster the hopes that the United States will go back to great passenger railway service:

First, when we had great trains, they were used mainly by the elite, and that remains true of great trains in other countries today. Before 1910, it is likely that a majority of Americans had never traveled more than 50 miles from home, and most had never been on a train, while many others had taken only one or two train trips in their life. As James Hill observed, “the so-called ‘travelling public’ forms in reality but a small, and the more fortunate class of the community.” If he was prejudiced against passenger trains, as some claim, it may have been for altruistic reasons, as the people who relied on freight trains “direct and indirect, include all. Hence justice requires that railway systems … should be cautious not to favor passenger traffic at the necessary expense of freight payers.” It is neither sensible nor fair fo the government to subsidize transportation catering mainly to the wealthy.

Second, new transportation technologies have replaced trains and streetcars. Planes are faster and less expensive for long distances; cars and buses are more convenient and less expensive for short distances; and there is no midrange distance at which passenger rail has an advantage over both cars and planes.

Third, and just as important, other new technologies, including the moving assembly line, telecommunications and the electrical grid, have reshaped our cities so the urban patterns that once made rail convenient to large numbers (though never a majority) of people have been replaced by patterns in which rail makes no sense for passenger travel.

Although we might want great trains in our fantasy of what the world should be like, the reality is we don’t need trains. Most Americans don’t ride the trains we have, nor would they ride them even if they met some arbitrary devinition of “great.” We love passenger trains, and we will remember them in museums and tourist lines. But if the government stays involved in transportation at all, it should be to prepare for the next revolution in transportation, not to try to reverse the previous one.

June 17, 2018

QotD: “Progress”

If you have always believed that everyone should play by the same rules and be judged by the same standards, that would have gotten you labeled a radical 50 years ago, a liberal 25 years ago and a racist today.

Thomas Sowell, “A Few Assorted Thoughts About Sex, Lies And Human Race”, Sun Sentinel, 1998-11-28.

February 19, 2018

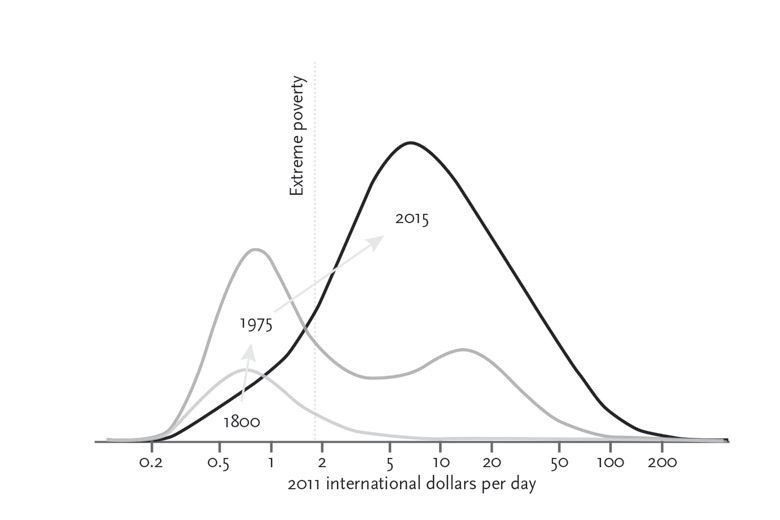

Graphing good news

In the Times Literary Supplement, David Wootton reviews Enlightenment Now: A manifesto for science, reason, humanism and progress by Steven Pinker:

This book consists essentially of seventy-two graphs – and, despite that, it is gripping, provocative and (many will find) infuriating. The graphs all have time on the horizontal axis, and on the vertical axis something important that can be measured against it – life expectancy, for example, or suicide rates, or income. In some graphs the line, or lines (often the graphs compare trends in several countries) fall as they go from left to right; in others they rise. In every single one, the overall picture (with the inevitable blips and bounces) is of life getting better and better. Suicide rates fall, homicides fall, incomes rise, life expectancies rise, literacy rates rise and so on and on through seventy-two variations. Most of these graphs are not new: some simply update graphs which appeared in Pinker’s earlier The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011); others come from recognized purveyors of statistical information. The graphs that weren’t in Better Angels extend the argument of that book, that war and homicide are on the decline across the globe, to assert that life has been getting better and better in all sorts of other respects. The claim isn’t new: a shorter version is to be found in Johan Norberg’s Progress (2017). But the range and scope of the evidence adduced is new. The only major claim not supported by a graph (or indeed much evidence of any kind) is the assertion that all this progress has something to do with the Enlightenment.

Since the argument of the book is almost entirely contained in the graphs, those who want to attack the argument are going to attack the figures on which the graphs are based. Good luck to them: arguments based on statistics, like all interesting arguments, should be tested and tested again. Better Angels caused a vitriolic dispute between Pinker and Nassim Nicholas Taleb as to whether major wars are becoming less frequent. In Taleb’s view the question is a bit like asking whether major earthquakes are getting less frequent or not: they happen so rarely, and so randomly, that you would need records going back over a vast stretch of time to reach any meaningful conclusion; a graph showing falling death rates in wars over the past seventy years won’t do the job. But it certainly will tell you that lots of generalizations about modern war are wrong. Much, indeed most, of Pinker’s argument survived Taleb’s attack, which in any case was directed at only one graph among many.

A more radical line of criticism of Better Angels came from John Gray. How can one find a common standard of measurement for the suffering of a concentration camp victim, of a soldier who died in the trenches, and of someone killed in the firebombing of Dresden? To turn to economics, how can one find a common standard of measurement for books and washing machines, oranges and steak pies? Money, you might think, provides that standard, but what happens if many of the goods being measured – electric lighting, cars, televisions, computers – get cheaper and cheaper as time goes on, so that a rising standard of living is concealed by falling prices? For Gray, to place one’s faith in statistics, which claim to be measuring the unmeasurable, is no different from believing in conversations with angels or in the efficacy of Buddhist prayer wheels. Quantification is our religion.

October 18, 2017

QotD: The course of economic progress in a nutshell

It is customary in these days of “slow food” to sneer at these devices, to aver that a real cook doesn’t need more than a cast-iron dutch oven, a good chef’s knife and a sense of adventure. As someone who took herself off to Chicago for three months with pretty much exactly this set of equipment (okay, also an electric pressure cooker), I can testify that this is true — sort of. You can get by with a very minimal set of equipment if you know how to cook. But as someone who has done so, I have to ask: Why would you?

I mean, yes, I know how to chop onions just fine. But doing so makes me cry like the dickens, unless I wear goggles. I know how to make great lemon curd, béchamel, hollandaise, caramelized onions. But my Thermomix makes them just as well, and I can read a novel instead of standing at the stove, stirring. I can whisk up an angel food cake in a copper bowl … or I could let the stand mixer do that, and my arms won’t hurt.

For that matter, I could also go out and grow my own wheat, mill it myself, and then mine some salt and cultivate some wild yeast to bake bread. But I don’t do these things, because subsistence farming is actually pretty arduous and unrewarding, which is why few of us have chosen to live off the grid. I see no reason to romanticize the grunt labor of the kitchen. If a machine does it as well as I do, and fits in my paycheck, I’ll happily outsource to the machine, and save my labor for the stuff the machine can’t do. This being basically the entire history of human economic progress to date.

Megan McArdle, “Give Thanks for Williams-Sonoma and the Garlic Press”, Bloomberg View, 2015-12-07.

December 10, 2015

Your business model and transformative change

At The Arts Mechanical, there’s a paean to the amazing technological achievement represented by this steam engine:

… and a return to reality by looking at how that amazing steam engine was made utterly obsolete by a humble diesel switcher and its direct descendants:

Which brings us to the picture at the head of this post. Anybody ever hear of Lima Locomotive? Here is what they did. That is a C&O RR H8 Allegheny. It is the largest and most powerful steam locomotive ever built. The locomotive was in the shed and there was no way I could get a side shot but the size of it boggles the mind. The firebox is the same size as a small house. The locomotive was designed to move mountains of coal and that’s what it did.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2-6-6-6

It was also obsolete before it was erected.