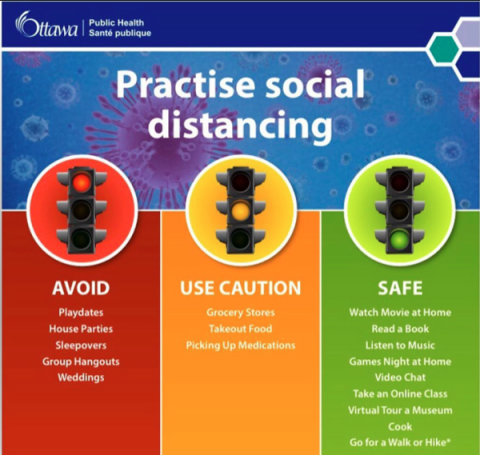

Getting back to “normal” is going to be much more difficult now that the powers-that-be know for certain that we’re all quite comfortable tugging the forelock and bending the knee given the right kind of orders:

As for the collective or political lessons of the epidemic, I fear them more than rejoice in them. They seem to me likely to reinforce a tendency to authoritarianism, and to embolden bureaucrats with totalitarian leanings. One of the surprising things (or perhaps I should say the things that surprised me) was how meekly the population accepted regulations so drastic that they might have made Stalin envious, all on the say-so of technocrats whose opinions were not completely unopposed by those of other technocrats. There was, as far as I can tell, no popular demand for the evidence that supposedly justified the severe limitations on freedom that were imposed on the population. I suppose an encouraging interpretation of this readiness of the population to do as it was told is that it demonstrated that, all the froth and foam of opposition to political leaders notwithstanding, fundamentally the authorities were trusted by the population to do the right thing. Much as we lament, therefore, the intellectual and moral level of our political class, there are limits to how much we despise it. In other words, we believe that our institutions still work even when guided or controlled by nullities.

A less optimistic interpretation, as usual, is possible. Our population is now so used to being administered, supposedly for its own good, under a regime of bread and circuses, that it is no longer capable of independent thought or action. We have become what Tocqueville thought the Americans would become under their democratic regime, namely a herd of docile animals. Only at the margins — for example, the drug-dealers of banlieues of Paris — would the refractory actually rebel against the regulations, and that not for intellectual reasons or in the name of freedom, but because they wanted to carry on their business as usual. (I should perhaps mention here that I number myself among the sheep.)

In Britain, at any rate, the epidemic revealed how quickly the police could be transformed from a civilian force that protects the population as it goes about its business into a semi-militarised army of quasi-occupation. This transformation is not entirely new, alas; it has been a long time since the policeman was the decent citizen’s friend. Under various pressures, not the least of them emanating from intellectuals, he has become instead a bullying but ineffectual keeper of discipline, whom only the law-abiding truly fear.

I first sensed this development many years ago this when a traffic policeman asked to see my licence. “Well, Theodore …” he started, calling me by my first name when a few years before he would have called me “Sir.” This change was significant. I had gone from being his superior, as a member of the public in whose name he exercised his authority, to being a kind of minor, whom it was his transcendent right to call to order. He was now the boss, and I was now the underling.

The change in uniform, too, has worked in the same direction. Traditionally, since the time of Sir Robert Peel, the uniform of the British policeman was unthreatening, deliberately so, his authority moral rather than physical. Now, he is festooned with the apparatus of repression, if not of oppression, though in effect he represses very little of what ought to be repressed in case it fights back. The modern police intimidate only those who do not need deterring; those who do need it know that they have nothing much to fear from these whited sepulchres, these empty vessels. Incidentally, the French police have undergone a similar deterioration in appearance: gone is the reassuring képi in favour of the moron’s baseball cap, and some of them now dress in jeans with a black shirt with the word POLICE across its back, which is not difficult to imitate and makes it impossible to know whether a policeman really is a policeman or a lout in disguise.

French Gendarmerie at the Eurockéennes of 2007.

Photo by Rama via Wikimedia Commons.

The Covid-19 epidemic has come as a great boon to the British police. Increasingly criticised for their concentration on pseudo-crimes such as hate speech at the expense of neglecting real crimes such as assault and burglary, to say nothing of organised sexual abuse of young girls by gangs of men of Pakistani origin, they could now bully the population to their heart’s content and imagine that in doing so they were performing a valuable public service, preserving the law and public health at the same time. Thus they transformed their previous moral and physical cowardice into a virtue.

Of course, in bullying the average citizen who was very unlikely to retaliate they took no risks, unlike with genuine wrongdoers and law-breakers, who tend to be dangerous; but the fact remains that most individual policemen joined the force motivated by some kind of idealism, a desire to do society some service, though they soon had these naïve fantasies knocked out of them by the morally corrupt or bankrupt leadership of the hierarchy which owes its ascendency to its willingness to comply with the latest nostrums of political correctness. The faint embers of the policeman’s initial idealism were no doubt rekindled by the opportunity to prevent the spread of the virus, as they supposed that they were doing, but some of them, at least, far exceeded even their flexible and vaguely-defined authority and began to inspect citizens’ shopping bags to determine whether they were hoarding goods that might be in short supply. This was a step too far, and at last there were protests; the police desisted.