During the first lockdown, I often found myself going to bed with two especially charming gentlemen. The first was a boisterous Old Etonian called Bertie, who took understandable pride in his aptitude for theology (and, indeed, won the prize for Scripture Knowledge at his prep school), and whose conversation usually involved reference to his club, the Drones, and the unfortunate incident where he served a night in the cells for knocking off a policeman’s helmet during Boat Race festivities. And the other man – Reginald, though he preferred to be known as Jeeves – was of a more sombre and serious mien. Quieter and more reserved than his companion, he was less free with his opinions and chatter, but what he said revealed a serious and deep intellectual commitment and purpose, albeit one leavened with a degree of good-humoured and entirely understandable exasperation at his charge’s more whimsical and mercurial antics.

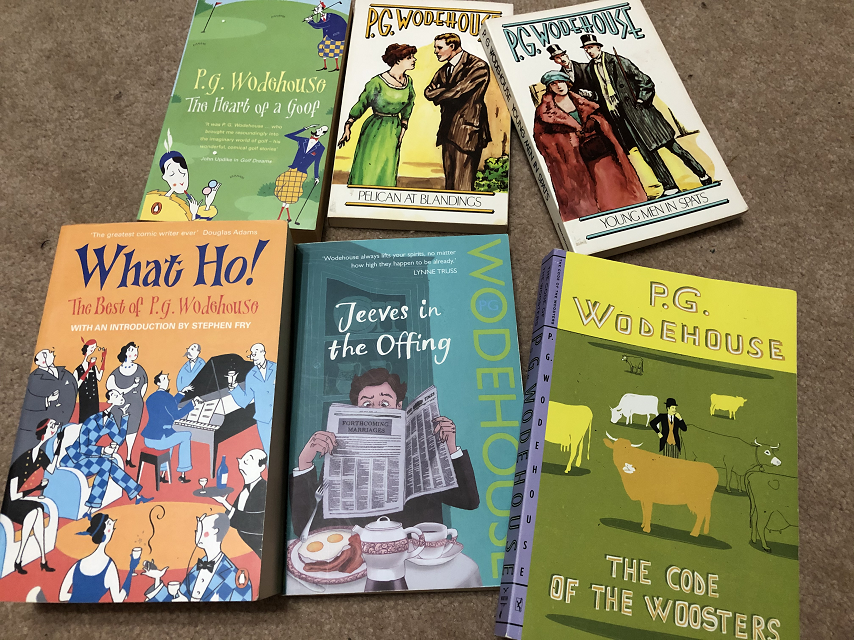

Everybody has those books, and authors, that they go to when they are in need of escapism. For me, PG Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster series have always been these tales. Nightly incursions into their pages during the pandemic made the misery and boredom of those long days and weeks considerably more bearable. He wrote 35 short stories and 11 novels featuring the duo, beginning in 1915 with Extricating Young Gussie (although purists prefer to begin with Leave it to Jeeves which appeared the following year and features the most recognisable incarnation of the characters), and ending shortly before his death in 1975 with 1974’s Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen. Undoubtedly, if Wodehouse had somehow lived another five or ten years, there would have been more stories, but his prolific dedication to “the graft” has left us with a truly splendid collection of tales, all revolving around a pre-lapsarian world that was always a fantastical creation, even when Wodehouse began writing. By the time of the last book’s publication, when Britain was immersed in the three-day week and the dying days of the Heath government, the events depicted bore as much relation to readers’ everyday lives as if Wodehouse had been writing about events on Mars.

This was, of course, the point from the beginning. As Evelyn Waugh, a great admirer, famously said, “Mr. Wodehouse’s idyllic world can never stale. He will continue to release future generations from captivity that may be more irksome than our own. He has made a world for us to live in and delight in.” Nobody has ever sat down to read about the adventures of Jeeves, Bertie, Bingo Little, Gussie Fink-Nottle, the terrifying Aunt Agatha and Roderick Spode (to say nothing of his black short-wearing followers) and expected gritty social realism.

Instead, they have come to marvel at the twentieth century’s greatest comic prose stylist’s apparently endless invention, in which matrimony is a predicament to be averted at all costs, where the distaste of one’s gentleman’s gentleman for an ill-considered sartorial faux pas can lead to a (happily temporary) breakdown in amicable relations, and where the sole work undertaken by Bertie is to contribute an article about “What the well-dressed man is wearing” to his aunt’s periodical. Like his prize for scripture knowledge, he remains proud of this modest achievement, and continually refers to it throughout his adventures.

Alexander Larman, “The enduring appeal of Jeeves and Wooster”, The Critic, 2020-10-16.

March 5, 2021

QotD: P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster

March 3, 2021

QotD: Big game hunting

It was a confusion of ideas between him and one of the lions he was hunting in Kenya that had caused A. B. Spottsworth to make the obituary column. He thought the lion was dead, and the lion thought it wasn’t.

P.G. Wodehouse, Ring for Jeeves.

January 4, 2021

Getting started reading the works of P.G. Wodehouse

I only started reading any of P.G. Wodehouse’s wonderful body of work a few years ago — I can’t imagine why I waited that long — but because there are so many books and short stories to choose from, it may be hard to decide where to begin. If you find yourself in that situation, the P.G. Wodehouse reading guide from Plumtopia may be of interest:

So you’d like to give P.G. Wodehouse a try, but don’t know where to start? Or perhaps you’ve read the Jeeves stories and want to discover the wider world of Wodehouse.

You’ve come to the right place.

There is no correct approach to reading Wodehouse. If you ask a dozen Wodehouse fans, you’ll get at least a dozen different suggestions — and picking up the first book you come across can be as good a starting point as any. But if you want more practical advice, this guide will help you discover the joys of Wodehouse — from Jeeves and Wooster to Blandings, and the hidden gems beyond.

Bertie Wooster & Jeeves

Bertie Wooster and his manservant Jeeves are P.G. Wodehouse’s most celebrated characters. They appear in a series of short stories and novels, all masterfully crafted for optimum joy. Bertie Wooster’s narrative voice is one of the greatest delights in all literature.[…]

Blandings

Evelyn Waugh put it best when he said: “the gardens of Blandings Castle are the original gardens of Eden from which we are all exiled.”Lord Emsworth wants only to be left alone to enjoy his garden and tend to his prize winning pig, the Empress of Blandings, without interference from his relations, neighbours, guests and imposters. So many imposters.

[…]

Psmith

Psmith (the “p” is silent as in pshrimp) made his first appearance in an early Wodehouse school story. Wodehouse knew when he was onto a good thing, and Psmith made the transition to adult novels along with his author. Adoration for Psmith among Wodehouse fans borders on the cultish, and for good reason (he certainly makes me swoon).[…]

Ukridge

The character Wodehouse readers love to hate, Ukridge is a blighter and a scoundrel, but his adventures are comedy gold. If you’ve ever had a friend or relation who pinches items from your wardrobe without asking, and is perpetually “borrowing” money, this series is for you.

March 6, 2020

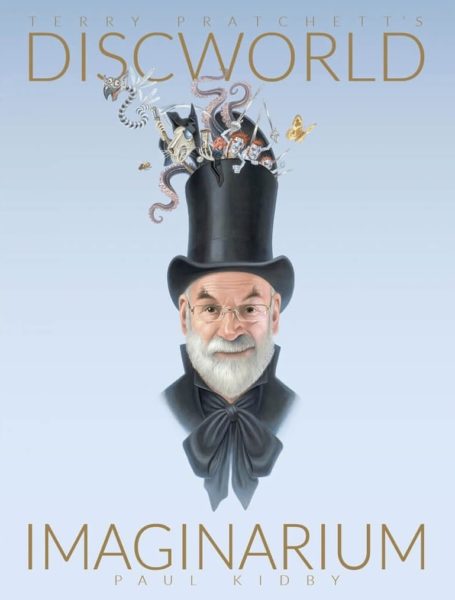

Some of the early influences on Terry Pratchett’s writing

That is, the books that made him love reading and how he incorporated those early works into his own style. This is from a very late interview with Tom Chivers published after his death in 2015:

“I wasn’t particularly interested in books,” he says. “And my mum, God bless her, she rolled up her sleeves and gave me a penny per page, and it worked beautifully. I think she only gave me about thruppence, because the third book was The Wind in the Willows.” He was so enthused after this, she no longer needed to pay him. Indeed, Pratchett got a job in Beaconsfield library. “You’re talking to a man who thinks, mostly, that his school days assisted him not at all, but the library did, in spades.” He looks at me sharply. “You, when you were young, read lots of books, didn’t you? A –” he pauses, and chooses his next word carefully – “a —-load, I believe?” I did, I reassure him. “A library boy. I recognise the kind. I was the same.” He had an indifferent time at school – he grumbles about the “death or glory” nature of the 11-plus (he passed easily), and about old teachers who had a grudge against him at the High Wycombe Technical High School (“sort of half a grammar school. A big woodwork place”). But the fire kindled by Kenneth Grahame, and Ratty, Mole and Badger, grew, and blazed.

Pratchett’s own sense of humour, a sort of gentle, English, observational thing, stems from this period. “Wodehouse, obviously, but also I tore my way through the Just William books. Richmal Crompton was a very good writer. I think it was from her that I learnt irony. It took me a while to work it out.” Do you think you could define irony, I ask him. “Sort of like iron.” I deserved that, I acknowledge. “When you get hit on the head with it, you know it.”

He also fell in love with RJ Yeatman and WC Sellar, authors of 1066 and All That (“in the Thirties, when the middle classes were getting richer, the two of them really got as much fun out of that as you could. The Thirties were an awful lot of fun. Or at least until the end. Bad ending, the decade, admittedly”) and fell out with his headmaster for “bringing in a copy of Mad magazine. How horrible! And a copy of Private Eye. Seditious.” But it was the now defunct satirical magazine Punch which really formed the comic voice in which he now speaks. “I read my way through all the bound Punches. It was the best way to read history; you got it without granny looking over your shoulder, and it was just astonishing.

“And just about any writer of distinction, anywhere in the English language, worked for Punch. Mark Twain. Jerome K Jerome. And they spoke with the same voice, which opened the door for me – the same kind of slightly satirical, people-are-rather-silly-but-they’re-not-that-bad voice, friendly about humanity, fond of its foibles.” Apart from the books, the other influences of his youth are clear in his own writing – especially the later Ankh-set works, in which he frequently extols the virtues of the poor-but-respectable people living in tiny, tidy terraced houses, and of the self-made men and women. “There used to be a sort of dignity in labour,” he says. “I don’t think there is now.”

He has spoken, often, of how his time on local newspapers made him. He started at 16, in high dudgeon at his headmaster: “On my last day at the school, I left all my stuff behind and phoned up the editor of a local newspaper. He actually used some cliché like, ‘I like the cut of your jib, young man’, or something.” It is the stuff of legend that he saw his first dead body the next day, “work experience really meaning something in those days”, as he put it in his author’s bio in his books.

“Truthfully, without over-egging it, as I often do,” he says, “the library and journalism, those things made me who I am. Journalism makes you think fast. You have to speak to people in all walks of life. Especially local journalism. London journalism can p— in someone’s face and they can’t do anything about it. Try that in local journalism, and someone’s down to complain. Everyone should have one local journalism job in their lives, especially if they’re a nosy parker.” He talks of local journalists in the same way he does his parents, with a sense of quiet heroism. “I interviewed an elderly journalist who’d worked in a small town for a very, very long time. I asked: is it boring? And he said: over there, that’s where a couple pushed their daughter into the attic because she’d had a black baby. And over there, that’s where a man was caught in flagrante delicto with a barnyard fowl. And he’d said to the magistrates, ‘Well, it was my fowl’. Even those small moments, they make you realise the world is not as you thought.”

April 26, 2018

QotD: Drama critics

Nobody loves them, and rightly, for they are creatures of the night. Has anybody ever seen a dramatic critic in the daytime? I doubt it. They come out after dark, and we know how we feel about things that come out after dark. Up to no good, we say to ourselves.

P.G. Wodehouse, Over Seventy: An Autobiography with Digressions, 1956.