Who would ever have thought of combining wireless computing with sexual appliances? Nobody, right? There’s no possible way that anyone could have even imagined such a thing could happen … otherwise this patent would not have been issued:

Alright, people, strap in and keep the laughter to a minimum because we’re going to talk dildos here. Specifically, remotely operated dildos, and other sex apparatuses, including those operated by Bluetooth connections or over the internet. It seems that in 1998, a Texan by the name of Warren Sandvick applied for a patent that casts an awfully wide net over remotely controlled sexual stimulation, specifically any of the sort that involves a user interface in a location different from the person being stimulated. You can find the patent at the link, but here’s the abstract:

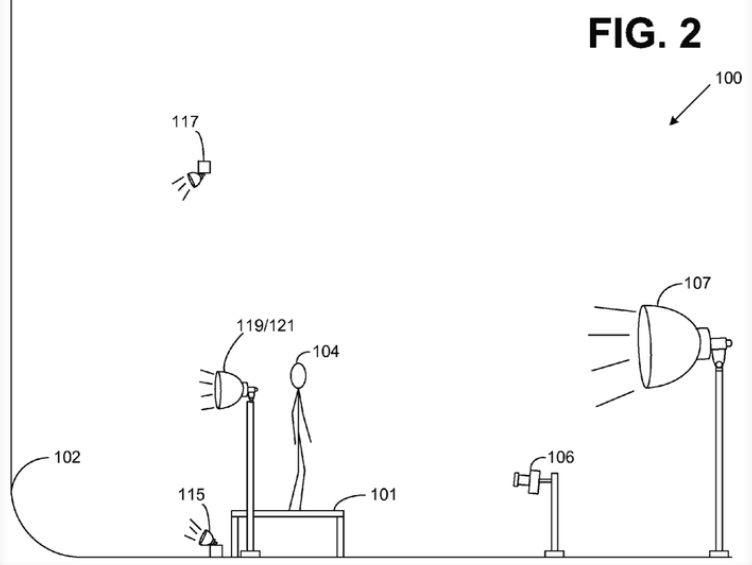

An interactive virtual sexual stimulation system has one or more user interfaces. Each user interface generally comprises a computer having an input device, video camera, and transmitter. The transmitter is used to interface the computer with one or more sexual stimulation devices, which are also located at the user interface. In accordance with the preferred embodiment, a person at a first user interface controls the stimulation device(s) located at a second user interface. The first and second user interfaces may be connected, for instance, through a web site on the Internet. In another embodiment, a person at a user interface may interact with a prerecorded video feed. The invention is implemented by software that is stored at the computer of the user interface, or at a web site accessed through the Internet.

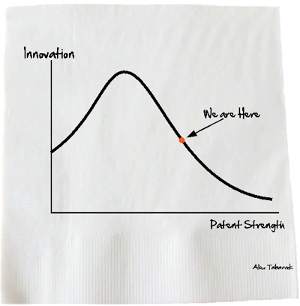

Great, except that nothing in the above is an actual invention; it’s essentially an acknowledgement that a dildo could be controlled remotely and an attempt to lay claim to that function exclusively. The description of the art outlaid in the patent rests solely on the claim that sexual stimulation devices have always been either self-stimulation devices or that any remotely operated stimulation devices still required close proximity. But it all rests on what you consider a stimulation device.

Even before this patent was filed, there was a term for this kind of thing in use: teledildonics.