HardThrasher

Published 30 Aug 2024Please consider donations of any size to the Burma Star Memorial Fund who aim to ensure remembrance of those who fought with, in and against 14th Army 1941–1945 – https://burmastarmemorial.org/

(more…)

August 31, 2024

Forgotten War Ep2 – You Walk, You Walk Or You Die Mate

March 24, 2024

Gahendra: the Nepalese Not-A-Martini

Forgotten Weapons

Published Jul 8, 2018(This video has been updated from its original form to fix translation issues and to clarify that Nepal was not, in fact, a British colony. Originally published January 10, 2017.)

Long a mysterious unknown member of the Martini family, the Nepalese Gahendra rifles finally became available in the US and Europe after IMA purchased Nepal’s cache of historic arms. The Gahendra is a uniquely Nepalese design built to sidestep British reluctance to supply military arms to the country. Developed by a General Gahendra (who is also responsible for the Bira copy of the Gardner Gun), the rifle is not actually a Martini at all. Instead, it shares its mechanical features mostly with the earlier Peabody falling block rifles, using a hammer and flat mainspring (the Martini improvement replaces there with a striker and coil spring).

Gahendras are chambered for the standard British .577/.450 Martini cartridge, although their bore diameters vary substantially, and one should absolutely slug a specific rifle before loading ammunition for it. In fact, unless you are capable of proficiently assessing the safety of the Gahendra, it is wiser not to shoot them at all. These rifles were individually handmade well over a hundred years ago using steels of questionable metallurgy and hardening.

That said, the guns were actually much better made than most people assume, considering their non-interchangeable parts. Craftsmen built each rifle part by part, giving the factory an output of just four rifles per day. Production began in the 1880s, and according to the Nepalese government ended prior to 1899. Dates on the rifles, however, are commonly found as late as 1911. These dates are generally assumed to be inventory or refurbishment dates.

(more…)

February 1, 2024

The Kohima Epitaph: Britain’s Forgotten Battle That Changed WW2

The History Chap

Published 9 Nov 2023What is the Kohima Epitaph and what has it got to do with Britain’s forgotten battle that changed the Second World War? Well, those of you living in the UK and who attend Remembrance Sunday services will probably know the words even if you don’t know the story behind them:

“When you go home, tell them of us and say,

For your tomorrow, We gave our today.”The memorial which bears those powerful words, stands in a cemetery containing the graves over over 1,400 British servicemen and memorials to over 900 Indian troops who died alongside them. They died in one of the bloodiest, toughest, grimmest battles of the Second World War. A battle sometimes called the “Stalingrad of the East.”

Outnumbered 6:1 and half of whom were from non-combat units, the multi-national British garrison stood their ground in bloody hand-to-hand fighting, refusing to retreat or surrender for two weeks until relieved. And even then the battle continued for another vicious month. That stand stopped the Japanese invasion of India in its tracks and turned the tide of the war in South East Asia. Both for its ferocity and its turning point in the war, it has been called: “Britain’s greatest battle”.

The Japanese lost 53,000 men from their army of 85,000.

The British (14th Army) lost 4,000 men killed and wounded.This forgotten victory was made possible by General William (Bill) Slim commanding the 14th Army. Rather like the battle and the 14th Army, General Slim has not received the recognition that he is due. And yet, it is almost completely forgotten. Rather like the army that fought against the Japanese in Burma.

So, as we near Remembrance Sunday, I think it is time to reveal the story of the Battle of Kohima in 1944.

(more…)

January 23, 2024

The battle of Sangshak, 1944

Dr. Robert Lyman discusses a new book by David Allison that covers one of the many small battles that made up the large Imphal-Kohima campaign:

When Wavell, by then Viceroy of India, visited Imphal after the battle in October, to bestow knighthoods on the four victors — Lieutenant Generals Bill Slim (14 Army), Montagu Stopford (33 Corps), Geoffrey Scoones (4 Corps) and Philip Christison (15 Corps) — he admitted to Slim that he found the battle hard to follow, as it seemed to have been fought in “penny-packets”. In professing his ignorance of Slim’s great triumph, Wavell nevertheless hit the nail on the head. Sangshak was one of those penny-packet fights which cumulatively determined the outcome of Japan’s audacious invasion of India.

Like many battles in insufficiently examined wars, Sangshak has suffered over the years from a paucity of rigorous examination. Louis Allen’s magisterial The Longest War gave it short treatment in 1984, and very little else. Until now. I’m delighted to say that a Hong Kong-based Australian lawyer with a military background — David Allison — has produced a new account of this crucial battle, and it is absolutely outstanding. It can be purchased here. I recommend it very strongly. It’s not long: at 159-pages of text you can make your way through this in a couple of days, but it is diligently researched, well written and judiciously argued. For those who know something of the battle, the big arguments in the past about the state training of the 50 Indian Parachute Brigade, the temporary breakdown of its commander, Hope-Thomson and the supposed loss of the captured Japanese map and orders by HQ 23 Indian Division, are calmly and satisfyingly explained.

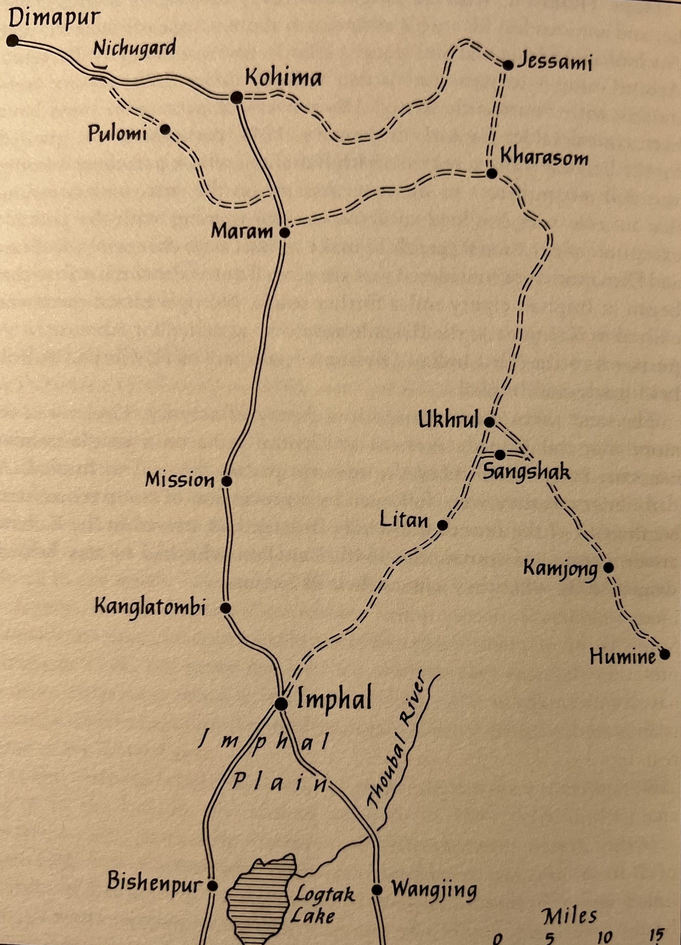

The story can be briefly told. The territory to the north-east of Imphal (centring on the Naga village of Ukhrul) had only the lightest of garrisons and no real defences. Until 16 March it was home to 49 Brigade, which was then despatched to the Tiddim Road to deal with the advance in the south of Lieutenant General Yanagida’s 33 Division. The brigade had considered itself to be in a rear area, and, extraordinarily, no dug-in and wired defensive positions had been prepared. It was one of the most serious British planning failures of the campaign. The entire north-eastern portion of Imphal lay effectively undefended. The gap left by the brigade’s departure had been filled in part by the arrival of the first of the two battalions of the newly raised 50 Indian Parachute Brigade (comprising the Gurkha 152 Battalion and the Indian 153 Battalion), whose young and professional commander, 31-year-old Brigadier M.R.J. (“Tim”) Hope-Thomson, had persuaded New Delhi to allow him to complete the training of his brigade in territory close to the enemy. The area north-east of Imphal was regarded as suitable merely for support troops and training. At the start of March, the brigade HQ and one battalion had arrived in Imphal and began the leisurely process of shaking itself out in the safety of the hills north-east of the town. To the brigade was added 4/5 Mahrattas under Lieutenant Colonel Trim, left behind when 49 Brigade was sent down to the Tiddim Road. To Scoones and his HQ, the area to which Hope-Thomson and his men were sent represented the lowest of all combat priorities. Sent into the jungle almost to fend for themselves, it was not expected that they would have to fight, let alone be on the receiving end of an entire Japanese divisional attack. They had little equipment, no barbed wire, and little or no experience or knowledge of the territory. No one considered it worthwhile to keep them briefed on the developing situation. To all intents and purposes, 50 Indian Parachute Brigade was an irrelevant appendage, attached to Major General Ouvry Roberts’ 23 Indian Division for administrative purposes but otherwise left to its own devices.

Before long, information began to reach Imphal that Japanese troops were advancing in force on Ukhrul and Sangshak. Inexplicably, however, this information appeared not to ring any warning bells in HQ IV Corps in Imphal, which was preoccupied with the developing threat in the Tamu area where the main Japanese thrust was confidently predicted. On the night of 16 March, the single battalion of 50 Parachute Brigade took over responsibility for the Ukhrul area from 49 Brigade, which was hastily departing for the Tiddim Road. They had no idea that an entire Japanese division of 20,000 men was crossing the Chindwin in strength opposite Homalin. On 19 March, large columns of Japanese infantry were reported advancing through the hills.

No one had expected them to be where they were. But the first shock came to the Japanese 3/58 battalion (Major Shimanoe), part of Lieutenant General Sato’s 31 Division – troops whose objective was Kohima, and not Imphal – who were bloodily rebuffed by the determined opposition of the young Gurkha soldiers at an unprepared position forward of Sheldon’s Corner. The 170 Gurkha recruits refused to allow the 900 men of 3/58 to roll over them and inflicted 160 casualties on the advancing Japanese. In the swirling confusion of the next 36 hours, Hope Thomson and his staff kept their heads, attempting to concentrate what remained of the dispersed companies of 152 Battalion and 4/5 Mahrattas back to a common position at the village of Sangshak, which dominated the tracks southwest to Imphal.

It was at this now-deserted Naga village that Hope-Thomson, on 21 March, decided to group his brigade for its last stand, his staff desperately attempting to alert HQ 4 Corps in Imphal to the enormity of what was happening to the north-east. The Japanese columns infiltrated quickly around and through the British positions, heading in the direction of Litan. The Japanese now began days of repeated assaults on the position in a battle of intense bravery and sacrifice for both sides. Hope Thomson’s men could only dig shallow trenches, which provided no protection from Japanese artillery.

June 18, 2023

QotD: Good intentions do not automatically mean good results

The United Nations Children’s Fund is probably the greatest mass-poisoner in human history — not deliberately, of course, but inadvertently. It encouraged and paid for the drilling of tube wells in Bangladesh without realizing that the groundwater was dangerously high in arsenic content. It promoted the wells to reduce the infant mortality rate from infectious gastroenteritis and in this it succeeded. Indeed, it trumpeted its success to such an extent that it found it hard to recognize that, in the process, it had exposed tens of millions of people to arsenic poisoning, and was very late in recognizing its responsibility in the matter.

Another United Nations agency, its peacekeeping force in Haiti, was responsible for the most serious epidemic of cholera of the twenty-first century so far. Before 2010, cholera had been unknown in Haiti despite the country’s poverty and lack of hygiene. Then, from 2010 to 2018, it suffered outbreaks of cholera that have affected perhaps a tenth of the population and caused between 10,000 and 80,000 deaths (the exact figure will never be known).

The evidence suggests that cholera was brought to Haiti by United Nations peace-keeping troops from Nepal. Whether Haiti needed peacekeeping troops at all may be doubted: at the time it suffered from civil unrest rather than from war. One suspects that the peacekeeping force was employed more to keep the Haitians from leaving Haiti than to keep the peace.

Be that as it may, some Nepali troops arrived fresh from a cholera epidemic in Nepal, established a camp next to the Artibonite River from which many Haitians drew their water. The Nepalis emptied their sewage directly into the river, and some of them were infected with the cholera germ. There was soon an outbreak of cholera among the local population of extraordinary violence. The Haitians guessed at once that the Nepali troops had brought the cholera, but this was strongly denied.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Negligence and Unaccountability at the United Nations”, New English Review, 2019-07-09.

August 3, 2022

February 26, 2022

In The Highest Tradition — Episode 3

British Army Documentaries

Published 27 Oct 2021This third episode in a six-part series delving into the world of regimental tradition looks Gurkhas’ history and commitment to the British Army. They swear their oath of allegiance directly to Her Majesty the Queen and continue to revere “The Queen’s Truncheon”, which was awarded to them by Queen Victoria in recognition of their service during the Indian Mutiny.

© 1989

This production is for viewing purposes only and should not be reproduced without prior consent.

This film is part of a comprehensive collection of contemporary Military Training programmes and supporting documentation including scripts, storyboards and cue sheets.

All material is stored and archived. World War II and post-war material along with all original film material are held by the Imperial War Museum Film and Video Archive.

March 5, 2021

Colonial Troops Saving Their Masters – WW2 Special

World War Two

Published 4 Mar 2021Without the incredible support and sacrifice of troops from British and French colonies, the Allies would be having an even harder time withstanding the Axis onslaught. This episode looks at their formation and their fighting style.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @ww2_day_by_day – https://www.instagram.com/ww2_day_by_day

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesHosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Markus Linke and Indy Neidell

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Maria Kyhle

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Markus Linke

Edited by: Miki Cackowski

Sound design: Marek Kamiński

Map animations: Miki Cackowski, Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Colorizations by:

Daniel Weiss

Mikołaj UchmanSources:

Photo of French Saharan troops (1932), courtesy of Acln https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi…

Archives du département du Rhône et de la métropole de Lyon

The New York Public Library – Digital Collections

USMC Archives

IWM E 11584, CBM 2264, E 6605, IND 2864, IND 2290, K 1385

Picture of Sudanese Defense Force near Kufra Oasis, courtesy of Major PJ HurmanSoundtracks from Epidemic Sound

Johannes Bornlof – “Deviation In Time”

Hakan Eriksson – “Epic Adventure Theme 3”

Phoenix Tail – “At the Front”

Philip Ayers – “The Unexplored”

Johannes Bornlof – “The Inspector 4”

Fabien Tell – “Weapon of Choice”

Reynard Seidel – “Deflection”

Fabien Tell – “Other Sides of Glory”

Philip Ayers – “Please Hear Me Out”Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

World War Two

9 hours ago

As regular viewers will know, we try to give the most complete picture of World War Two possible by diving into the multitude of people that took part and seeing it from their unique perspective.This episode is part of that effort, looking at the colonial troops who fought on the side of their imperial administrators. In a different way, our On the Homefront series is also part of that effort, and we are happy to announce that we have just got started with it again. Check out the latest episode here where Anna looks at the changing role of the Geisha in wartime Japanese society: https://youtu.be/7Y3IYsNC1WM

October 28, 2020

QotD: The Gurkhas

For 20 years between the wars [Field Marshal Viscount Slim] was a Gurkha officer, as so many of the 14th Army’s fighting generals were. Indeed, for a time, they were known on the front as the “Mongol Conspiracy.” Slim loves the Gurkhas, whose language he speaks. His favourite stories are of Gurkhas. He tells of the paratroopers who were to jump at 300 feet. As they had never jumped before, their Havildar [Sergeant] asked if they might go a little nearer the ground for their first jump. He was told that this was impossible because the parachutes would not have time to open. “Oh,” said the Gurkha, “so we get parachutes, eh?”

June 9, 2019

Making the legendary service Khukuri/Kukri of British Gurkhas – KHHI Nepal

KHHI Nepal

Published on 26 Mar 2018See how a scrap of steel is converted into a piece of mastery craft by our men @ duty. All bear hands, hard labor, years of experience and great skill. Pls enjoy it!!

Is the original 2016-17 British Gurkhas Issue issued to the new recruits as their training, exercise, utility and even as a combat knife.

Product link :

https://www.thekhukurihouse.com/2016-17-british-standard-issue-bsi-2-kukri#makingkhukuri #bsikukri #servicekukri #gurkhaknife

July 17, 2018

Women to be eligible to join British army Gurkha units in 2020

The BBC reports on a recently announced change in Gurkha recruiting:

The Gurkhas will recruit women for the first time from 2020, and the selection process will be the same as for men.

Women hoping to join will have to pass gruelling physical tests – including racing 3.1 miles (5km) uphill carrying 55lb (25kg) of sand in a wicker basket.

Gurkhas, who are Nepalese, have been part of the Army for more than 200 years.

Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson said it was “right” women were given the chance to serve in “this elite group”.

The change in direction comes three years after Nepal – traditionally a male-dominated society – elected its first female president, Bidhya Devi Bhandari.

To be considered for the selection process, applicants must weigh more than 50kg (7.9 stone), be taller than 158cm (5ft 1in) and “be able to complete eight underarm heaves”, the Army website says.

The recruitment process takes place in Pokhara, central Nepal. Successful applicants are then flown to Catterick, North Yorkshire, for a 10-week training programme.

[…]

At its peak, during World War Two, 112,000 men were in the Gurkhas. More than 230,000 fought across both world wars, but their numbers have fallen dramatically since.

Currently, there are about 3,000 Gurkhas – most are in the infantry but some are engineers, logisticians or signals specialists.

The regiment, whose motto is “Better to die than be a coward,” still carry into battle their traditional weapon – an 18-inch (46cm) long curved knife known as a kukri.

March 30, 2018

Havildar Bhanbhagta Gurung’s Knife Wielding WWII Assault

Today I Found Out

Published on 19 Feb 2018In this video:

In March of 2008, the world lost one of the most fearless soldiers to have served during WWII; a man who single-handedly cleared five heavily fortified positions with nothing more than a knife, a few grenades, a rock, and a complete disregard for the bullets flying around him the whole time. This is the story of Bhanbhagta Gurung.

September 19, 2015

The Gurkhas – Full Documentry

Published on 7 Jun 2013

After great feedbacks from my previous Gurkha videos I decided to upload another one, this time more in depth and informative. Thanks for all the support guys and enjoy

Gurkhas have been part of the British Army for almost 200 years, but who are these fearsome Nepalese fighters?

“Better to die than be a coward” is the motto of the world-famous Nepalese Gurkha soldiers who are an integral part of the British Army.

They still carry into battle their traditional weapon – an 18-inch long curved knife known as the kukri.

In times past, it was said that once a kukri was drawn in battle, it had to “taste blood” – if not, its owner had to cut himself before returning it to its sheath.

Update: Pound-for-pound, the Gurkhas are the baddest of bad-asses you’d never want to meet on a battlefield.

August 7, 2015

Looking back at April’s 7.8 earthquake in Nepal

At Ars Technica, Scott K. Johnson what has been learned about the devastating earthquake that struck Nepal earlier this year:

The mighty Himalayas have been driven up into the sky by the collision of Eurasia and India, which has migrated north like a tectonic rocket over the last 100 million years. The Indian plate is being crammed beneath the crumpled Himalayan rocks along a dangerous fault that ramps downward to the north.

Lots of GPS sensors and seismometers have been deployed in the area to help seismologists study earthquakes here. Combined with precise satellite measurements of surface elevation changes, researchers have the means to work out where the movement on the fault must have occurred.

The earthquake began about 80 kilometers northwest of Kathmandu and about 15 kilometers beneath the surface. Geologists like to talk about faults “unzipping,” which is a helpful way to visualize what’s going on. A small patch of the fault plane slips, and then expands outward along the fault. In this case, the patch unzipped about 140 kilometers to the east in under a minute, traveling horizontally along the fault plane. Within that patch, the rocks slipped as much as six meters past each other.

Although it’s the seismic energy released by that sudden motion that causes the damage, the surface changes are still eye-catching — some of the GPS stations ended up two meters south of where they had been before the earthquake.

As for that seismic shaking, the pattern of building damage in Kathmandu was partly the result of the geology beneath the city. It sits on a roughly 500-meter-thick stack of lake and river sediment filling a bedrock bowl. The reverberation of seismic waves in that bowl produced a resonance, building stronger waves with a period of 4 to 5 seconds. While fewer homes were actually damaged than expected, taller buildings — which can sway at about that same frequency — didn’t fare as well. (A similar thing happened in the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, when buildings between 6 and 15 stories bore the brunt.)

July 25, 2015

Gurkhas in the SAS

Strategy Page on the (long overdue) inclusion of Gurkha troops in the British army’s elite Special Air Services (SAS) units:

It was recently revealed that the British SAS commandos have, since about 2010 recruited a dozen Gurkhas. The SAS, who were the original modern commandos and were first formed during World War II, are a very selective and elite organization. There are only about 200-300 SAS operators active and several years ago it was decided to recruit some Gurkhas. What was unusual about this was that the Gurkhas are not British and it is very rare for commando organizations to recruit foreigners. The Gurkhas are different in that they have served Britain loyally for a long time. While the Gurkhas are native to Nepal (a small country north of India) for two centuries Britain has recruited Gurkhas from the Gurkha tribes. This was mainly because Gurkhas have an outstanding reputation for military skills including discipline, bravery and all round kick-ass soldiering. Having served in the British Army, most can speak good English and all are familiar with British weapons, tactics and military customs.

There are currently 3,500 Gurkhas serving in the British army, and recruiting more is not a problem. Because of high unemployment in Nepal, a job in the British army is like winning the lottery. British military pay is more than 30 times what a good job in Nepal will get you. There are over sixty applicants for each of the few hundred openings each year. The men who don’t make it into the British army, can try getting into the Indian Army Gurkha units. There are about ten times as many Gurkhas in the Indian army, but the pay is only a few times what one could make in Nepal, and the fringe benefits are not nearly as good. Then again, you’re closer to home.

When the SAS quietly sought Gurkha recruits they found fifty willing to try out. A dozen of these passed the screening and survived the training. That’s a slightly higher pass rate than the usual SAS volunteers (British citizens serving in the army or Royal Marines). This was not surprising because Gurkhas have an outstanding military record. Such mercenary duty is now a tradition in the Gurkha tribes, where warriors, and things like loyalty and courage, have been held in high esteem for centuries. Nepal was never conquered by the British, although they did fight a war with the colonial British army in the early 19th century.