Published on 17 Jan 2017

This episode covers the various elements of castle fortification elements like towers, walls, moats, loopholes, gates, gatehouses, portcullises, battlements, hoardings, draw bridges, etc.

Military History Visualized provides a series of short narrative and visual presentations like documentaries based on academic literature or sometimes primary sources. Videos are intended as introduction to military history, but also contain a lot of details for history buffs. Since the aim is to keep the episodes short and comprehensive some details are often cut.

» SOURCES & LINKS «

Kaufmann, J.E; Kaufmann, H.W.: The Medieval Fortress – Castles, Forts, and Walled Cities of the Middle Ages.

Piper, Otto: Burgenkunde. Bauwesen und Geschichte der Burgen.

Toy, Sidney: Castles – Their Construction and History

September 3, 2017

Medieval Castles – Elements of Fortifications

September 2, 2017

[Medieval] Castles – Functions & Characteristics (1000-1300)

Published on 30 Sep 2016

» SOURCES & LINKS «

France, John: Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades 1000-1300#

Ohler, Norbert: Krieg & Frieden im Mittelalter

Contamine, Philippe: War in the Middle Ages

Pounds, Norman J. G. Pounds: Medieval Castle in England & Wales: A Political and Social History

http://faculty.goucher.edu/eng240/early_english_currency.htm

http://www.ancientfortresses.org/medieval-occupations.htm

https://www.britannica.com/technology/castle-architecture#ref257454

http://www.castrabritannica.co.uk/texts/text04.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harlech_Castle

July 26, 2017

April 29, 2017

If Walls Could Talk The History of the Home Episode 4: The Kitchen

Published on 2 Feb 2017

April 16, 2017

If Walls Could Talk The History of the Home Episode 3 The Bedroom

Published on 1 Feb 2017

April 5, 2017

If Walls Could Talk The History of the Home Episode 2: The Bathroom

Published on 31 Jan 2017

April 4, 2017

Archaeological evidence of corpse mutilation in deserted medieval village of Wharram Percy

A bit of gruesome post-death ritual from the middle ages in Wharram Percy:

Archaeologists investigating human bones excavated from the deserted mediaeval village of Wharram Percy in North Yorkshire have suggested that the villagers burned and mutilated corpses to prevent the dead from rising from their graves to terrorise the living.

Although starvation cannibalism often accounts for the mutilation of corpses during the Middle Ages, when famines were common, researchers from Historic England and the University of Southampton have found that the ways in which the Wharram Perry remains had been dismembered suggested actions more significant of folk beliefs about preventing the dead from going walkabout.

Their paper, titled A multidisciplinary study of a burnt and mutilated assemblage of human remains from a deserted mediaeval village in England, is published today in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Located in the Yorkshire Wolds, Wharram Percy was continuously occupied for about 600 years, and was probably founded in the 9th or 10th century, but had become deserted by the early 16th century as a result of gradual abandonment and forced evictions. The ruined church is the last-standing mediaeval building, beside it remaining the grassed-over foundations of two manors and about 40 peasant houses and their outbuildings.

Since 1948 the settlement has been the focus of intensive research, which has made it Europe’s best-known deserted mediaeval village, and in what may be the first good archaeological find regarding the practice, human remains from the site suggest the predominance of folk beliefs regarding revenants in 11th-13th century England.

February 28, 2017

How to Make Medieval Stocks – Torture Your Friends and Family With This DIY Pillory

Published on 7 Oct 2016

You can make this fun DIY medieval torture device in a weekend! FREE PLANS and full article►► http://woodworking.formeremortals.net/2016/10/how-to-make-medieval-stocks-pillory/

February 8, 2017

British History’s Biggest Fibs with Lucy Worsley Episode 1 War of the Roses [HD]

Published on 27 Jan 2017

Lucy debunks the foundation myth of one of our favourite royal dynasties, the Tudors. According to the history books, after 30 years of bloody battles between the white-rosed Yorkists and the red-rosed Lancastrians, Henry Tudor rid us of civil war and the evil king Richard III. But Lucy reveals how the Tudors invented the story of the ‘Wars of the Roses’ after they came to power to justify their rule. She shows how Henry and his historians fabricated the scale of the conflict, forged Richard’s monstrous persona and even conjured up the image of competing roses. When our greatest storyteller William Shakespeare got in on the act and added his own spin, Tudor fiction was cemented as historical fact. Taking the story right up to date, with the discovery of Richard III’s bones in a Leicester car park, Lucy discovers how 15th-century fibs remain as compelling as they were over 500 years ago. As one colleague tells Lucy: ‘Never believe an historian!

February 2, 2017

QotD: Noblesse oblige

I was raised with noblesse oblige, which, as we all know is a kind of almond and mare’s milk pastry made in the mountains of outer Mongolia and eaten at wedding feasts to assure good luck.

Okay, I lie. Noblesse Oblige is literally – as all of you know! However, let me unpack it, because sometimes it’s good to reflect on things we know – the obligations of noblemen.

In a world in which station was dictated by birth (most of the world, most of the time) the way to keep society from becoming completely tyrannical and the burden of those on the lower rungs of society from becoming unbearable was “noblesse oblige” – that is a set of obligations that the noblemen/those in power accepted as a part of their duty to society. Most of these involved some form of moderation of force.

The amount of moderation depended on the culture itself. For instance, in those lands in which the nobleman got first night rights (or claimed them anyway) it might be noblesse oblige to return the bride after that. It might also be noblesse oblige to stand godfather to the oldest child, who, after all, might be more than a godchild. And in other cultures, though the first night thing wasn’t there, the godchild thing still applied. A small return for faithful service to closer servants and courtiers, etc.

In the same way, while you might treat your serfs or villains like dirt, you forebore to take their last crumb of bread and left them enough to live on. This might not be because you were smart or merciful or whatever, but because someone had dinged it into you.

Noblesse oblige, by that name or others, appears every time there is a gross imbalance of power in human society. Or that is, it appears if society is to survive.

Sarah Hoyt, “Noblesse Oblige and Mare’s Nests”, According to Hoyt, 2015-05-05.

March 14, 2016

Pink Floyd – Another Brick in the Wall (Part II) (medieval cover by Stary Olsa)

Published on 5 Oct 2015

Stary Olsa performing “Another Brick in the Wall” by Pink Floyd for Belarusian TV-show “Legends. Live” on ONT channel.

Produced by Mediacube Production. (Minsk, Belarus)

If you’ve liked this or the earlier covers, you might like to know that Stary Olsa has a Kickstarter campaign to fund their next album called “Old Time Rock n Roll”, which will include this song and at least the following:

- “One,” by Metallica

- “Another Brick in the Wall” part II, by Pink Floyd

- “Californication,” by the Red Hot Chili Peppers

- “Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da” and “A Hard Day’s Night,” by the Beatles

- “Child in Time” by Deep Purple

- “Smells Like Teen Spirit” by Nirvana

September 20, 2015

The chastity belt – medieval “security” or renaissance in-joke?

The chastity belt was a device invented to preserve the chastity of Crusader knights as they rode off to defend the Holy Land. The chastity belt was an in-joke in theatre performances from the early fifteenth century onwards. One of these two statements is closer to the truth than the other, as Sarah Laskow explains that most of what you’ve heard about the chastity belt is false:

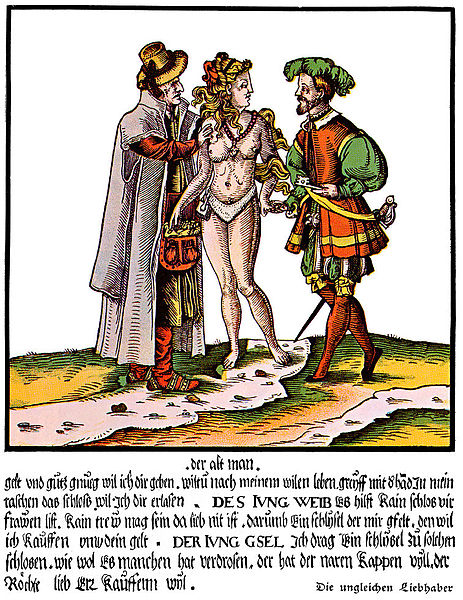

A 16th-century German satirical colored woodcut whose general theme is the uselessness of chastity belts in ensuring the faithfulness of beautiful young wives married to old ugly husbands. The young wife is dipping into the bag of money which her old husband is offering to give her (to encourage her to remain placidly in the chastity belt he has locked on her), but she intends to use it to buy her freedom to enjoy her young handsome lover (who is bringing her a key). (via Wikipedia)

What was the chastity belt? You can picture it; you’ve seen it in many movies and heard references to it across countless cultural forms. There’s even a Seattle band called Chastity Belt. In his 1969 book Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask), David R. Reuben described it as an “armored bikini” with a “screen in front to allow urination and an inch of iron between the vagina and temptation.” “The whole business was fastened with a large padlock,” he wrote. With this device, medieval men going off to medieval wars could be assured that their wives would not have sex with anyone else where they were far, far away, for years at a time.

Yes, it sounds simultaneously ridiculous, barbarous and extremely unhygienic, but … medieval men, you know? It was a different time.

This, at least, has been the story that’s been told for hundreds of years. It’s simple, shocking, and, on some level, fun, in that it portrays past people as exceeding backwards and us, by extension, as enlightened and just better. It’s also, mostly likely, very wrong.

“As a medievalist, one day I thought: I cannot stand this anymore,” says Albrecht Classen, a professor in the University of Arizona’s German Studies department. He set out to reveal the true history of chastity belts. “It’s a concise enough research topic that I could cover everything that was ever written about it,” he says, “and in one swoop destroy this myth.”

Here is the truth: Chastity belts, made of metal and used to ensure female fidelity, never really existed.

However, there is a small but thriving trade providing modern day chastity belts to eager BDSM fans, and they’re available in both male and female designs. I nearly described that as “equal opportunity”, but I guess “equal frustration-of-opportunity” is more like it. Feel free to Google image search those if you like, but be prepared for a fair bit of NSFW images if you do.

September 7, 2015

QotD: The Crusades

So what is the truth about the Crusades? Scholars are still working some of that out. But much can already be said with certainty. For starters, the Crusades to the East were in every way defensive wars. They were a direct response to Muslim aggression — an attempt to turn back or defend against Muslim conquests of Christian lands.

Christians in the eleventh century were not paranoid fanatics. Muslims really were gunning for them. While Muslims can be peaceful, Islam was born in war and grew the same way. From the time of Mohammed, the means of Muslim expansion was always the sword. Muslim thought divides the world into two spheres, the Abode of Islam and the Abode of War. Christianity — and for that matter any other non-Muslim religion — has no abode. Christians and Jews can be tolerated within a Muslim state under Muslim rule. But, in traditional Islam, Christian and Jewish states must be destroyed and their lands conquered. When Mohammed was waging war against Mecca in the seventh century, Christianity was the dominant religion of power and wealth. As the faith of the Roman Empire, it spanned the entire Mediterranean, including the Middle East, where it was born. The Christian world, therefore, was a prime target for the earliest caliphs, and it would remain so for Muslim leaders for the next thousand years.

With enormous energy, the warriors of Islam struck out against the Christians shortly after Mohammed’s death. They were extremely successful. Palestine, Syria, and Egypt — once the most heavily Christian areas in the world — quickly succumbed. By the eighth century, Muslim armies had conquered all of Christian North Africa and Spain. In the eleventh century, the Seljuk Turks conquered Asia Minor (modern Turkey), which had been Christian since the time of St. Paul. The old Roman Empire, known to modern historians as the Byzantine Empire, was reduced to little more than Greece. In desperation, the emperor in Constantinople sent word to the Christians of western Europe asking them to aid their brothers and sisters in the East.

That is what gave birth to the Crusades. They were not the brainchild of an ambitious pope or rapacious knights but a response to more than four centuries of conquests in which Muslims had already captured two-thirds of the old Christian world. At some point, Christianity as a faith and a culture had to defend itself or be subsumed by Islam. The Crusades were that defense.

Thomas F. Madden, “The Real History of the Crusades”, Crisis Magazine, 2002-04-01.

August 27, 2015

QotD: The real purpose of the Inquisition

In order to understand the Spanish Inquisition, which began in the late 15th century, we must look briefly at its predecessor, the medieval Inquisition. Before we do, though, it’s worth pointing out that the medieval world was not the modern world. For medieval people, religion was not something one just did at church. It was their science, their philosophy, their politics, their identity, and their hope for salvation. It was not a personal preference but an abiding and universal truth. Heresy, then, struck at the heart of that truth. It doomed the heretic, endangered those near him, and tore apart the fabric of community. Medieval Europeans were not alone in this view. It was shared by numerous cultures around the world. The modern practice of universal religious toleration is itself quite new and uniquely Western.

Secular and ecclesiastical leaders in medieval Europe approached heresy in different ways. Roman law equated heresy with treason. Why? Because kingship was God-given, thus making heresy an inherent challenge to royal authority. Heretics divided people, causing unrest and rebellion. No Christian doubted that God would punish a community that allowed heresy to take root and spread. Kings and commoners, therefore, had good reason to find and destroy heretics wherever they found them—and they did so with gusto.

One of the most enduring myths of the Inquisition is that it was a tool of oppression imposed on unwilling Europeans by a power-hungry Church. Nothing could be more wrong. In truth, the Inquisition brought order, justice, and compassion to combat rampant secular and popular persecutions of heretics. When the people of a village rounded up a suspected heretic and brought him before the local lord, how was he to be judged? How could an illiterate layman determine if the accused’s beliefs were heretical or not? And how were witnesses to be heard and examined?

The medieval Inquisition began in 1184 when Pope Lucius III sent a list of heresies to Europe’s bishops and commanded them to take an active role in determining whether those accused of heresy were, in fact, guilty. Rather than relying on secular courts, local lords, or just mobs, bishops were to see to it that accused heretics in their dioceses were examined by knowledgeable churchmen using Roman laws of evidence. In other words, they were to “inquire”—thus, the term “inquisition.”

From the perspective of secular authorities, heretics were traitors to God and king and therefore deserved death. From the perspective of the Church, however, heretics were lost sheep that had strayed from the flock. As shepherds, the pope and bishops had a duty to bring those sheep back into the fold, just as the Good Shepherd had commanded them. So, while medieval secular leaders were trying to safeguard their kingdoms, the Church was trying to save souls. The Inquisition provided a means for heretics to escape death and return to the community.

Most people accused of heresy by the medieval Inquisition were either acquitted or their sentence suspended. Those found guilty of grave error were allowed to confess their sin, do penance, and be restored to the Body of Christ. The underlying assumption of the Inquisition was that, like lost sheep, heretics had simply strayed. If, however, an inquisitor determined that a particular sheep had purposely departed out of hostility to the flock, there was nothing more that could be done. Unrepentant or obstinate heretics were excommunicated and given over to the secular authorities. Despite popular myth, the Church did not burn heretics. It was the secular authorities that held heresy to be a capital offense. The simple fact is that the medieval Inquisition saved uncounted thousands of innocent (and even not-so-innocent) people who would otherwise have been roasted by secular lords or mob rule.

As the power of medieval popes grew, so too did the extent and sophistication of the Inquisition. The introduction of the Franciscans and Dominicans in the early 13th century provided the papacy with a corps of dedicated religious willing to devote their lives to the salvation of the world. Because their order had been created to debate with heretics and preach the Catholic faith, the Dominicans became especially active in the Inquisition. Following the most progressive law codes of the day, the Church in the 13th century formed inquisitorial tribunals answerable to Rome rather than local bishops. To ensure fairness and uniformity, manuals were written for inquisitorial officials. Bernard Gui, best known today as the fanatical and evil inquisitor in The Name of the Rose, wrote a particularly influential manual. There is no reason to believe that Gui was anything like his fictional portrayal.

By the 14th century, the Inquisition represented the best legal practices available. Inquisition officials were university-trained specialists in law and theology. The procedures were similar to those used in secular inquisitions (we call them “inquests” today, but it’s the same word).

Thomas F. Madden, “The Truth About the Spanish Inquisition”, Crisis Magazine, 2003-10-01.

July 30, 2015

Stary Olsa covers the Red Hot Chili Peppers on medieval instruments

Published on 29 Apr 2015

Stary Olsa performing “Californication” by Red Hot Chili Peppers for Belarusian TV-show “Legends. Live” on ONT channel.

Produced by Mediacube Production. (Minsk, Belarus)

H/T to Open Culture.