On his Substack, Freddie deBoer wonders why we can’t be honest about the rise of bespoke “mental disorders” that look remarkably like typical human reaction to stimuli:

I will never not be fascinated by those issues or arguments or perspectives that are studiously ignored by the media generally and the New York Times in particular. I’ve whinged about this many times when it comes to education, as the NYT is simply not going to consider the notion that different individual people have fundamentally different levels of academic potential in its pages, not even in an attempt to rebut the idea. I suppose that notion is just too challenging to the elite meritocratic liberalism that the Times epitomizes; the idea that we are all ultimately capable of achieving academic and professional greatness flatters the high-achievers who read and write the paper, and the “anyone can be anything” ethos is pleasant and unchallenging. It’s also destructive, which is the point. Bad ideas grow like weeds in the shade, or whatever the saying is. Disability issues are another place where the Grey Lady is very picky about what ideas to consider, and as usual they set the rhythm for many other publications.

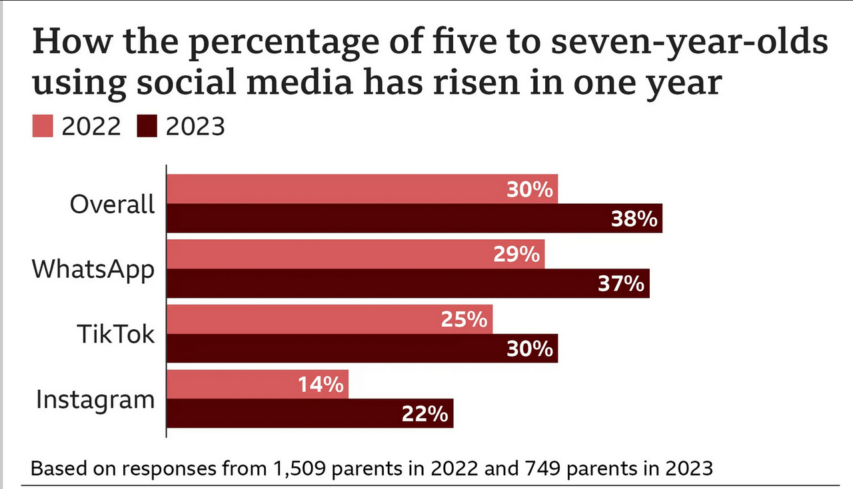

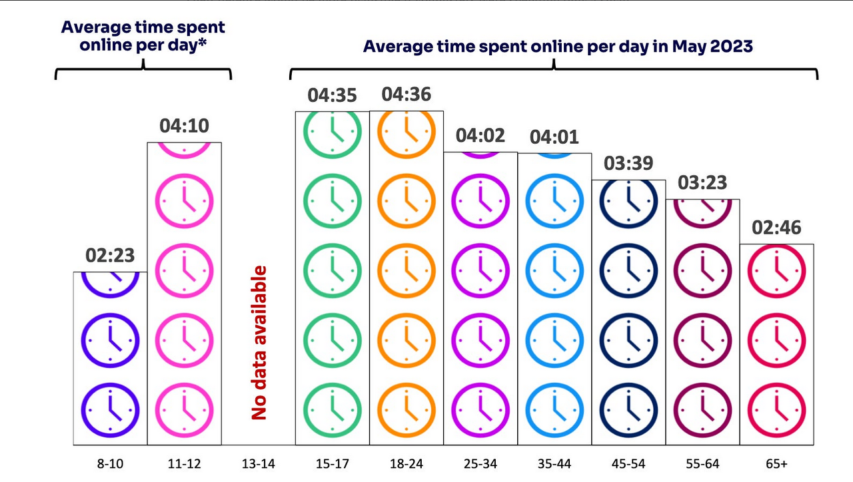

This weekend the Times released a long piece looking at the ever-escalating rates of ADHD diagnoses and what exactly they tell us. What’s in the piece is fine — of course, the ADHD activist class doesn’t like it — but what’s remarkable is what isn’t in it. Once again, there’s just about zero consideration of ADHD as a social contagion, any recognition that there is now a vast and deeply annoying ADHD culture online that acts as a kind of evangelical movement for a neurodevelopment disorder. There are millions of people on ADHD TikTok and ADHD Tumblr and ADHD Twitter. There’s a vast universe of facile memes, dubious statistics, and self-flattering nostrums about ADHD floating around out there, and increasingly they’re penetrating into broader internet culture. (I am genuinely unaware of a subculture that is more directly and shamelessly self-celebrating than the online ADHD community, and I’ve read the comments at LessWrong.) Unsurprisingly, a big subsidiary industry has sprung up, with all kinds of products and services for sale, books and apparel and tchotchkes and conferences and boutique forms of therapy and exclusive members-only Discords … Whether neurodevelopmental disorders should have merch is an open question. What’s not subject to questioning is that this is happening. Five minutes of cursory searching would reveal the remarkable scope of online ADHD culture.

And yet the piece’s author, Paul Tough, is just about totally silent on this glaring reality. I find it genuinely bizarre. In a long and rambling (in a good way) piece where he kicks the various rocks of ADHD and asks good-faith questions about how diagnostic rules and social perception of the disorder influence medical practice, he still somehow fails to ever refer to the large, influential, and growing online movement that has raised the profile of the disorder even beyond its prior notoriety and in doing so injected a ton of money into the equation. You can dismiss that community as an online sideshow if you choose, but of course the online world has become profoundly influential on real life, and in other contexts neither the New York Times specifically nor the elite media generally has any problem acknowledging that fact. Why not here?

This tendency extends beyond ADHD. Recently Holden Thorp, editor in chief of the prestigious journal Science, wrote an essay for the NYT that explores the rise of autism diagnoses, which have expanded at truly ludicrous rates. To the extent that it’s referenced at all, the idea of social contagion is dismissed without argument. A couple years ago the Times published a piece by Azeen Ghorayshi about the absurd case of Tourette’s spreading (or “spreading”) among too-online adolescent girls via TikTok; though Ghorayshi is admirably clear that those young women did not in fact have Tourette’s, her piece is also slavishly, almost comically sympathetic to them, never bothering to suggest that maybe these were just bored teenagers who engaged in a frivolous and offensive bit of minstrelsy. (Imagine, judging teenagers for doing something stupid!) The idea that anyone could ever have unserious and wrongheaded motivations for adopting a disability seems to be one of those stories that the New York Times absolutely refuses to tell.

But why? People make up fake illnesses all the time, both consciously and unconsciously. Factitious disorders are real; we have references to what we might now call psychosomatic illnesses that stretch back to antiquity. Munchausen by internet is real. Hypochondria, factitious illness, Munchausen’s, the worried well … these have represented a major challenge for psychiatry for as long as the field has been formalized and integrated into the larger medical project. Why does no one ever talk about this stuff in our stuffy elite publications? Why do so many people in our media dance and shuffle rather than ask direct questions like “How many of these diagnoses are fundamentally faulty?” Why can’t anyone point out that saying you have a medical disorder is a shortcut to getting sympathy and attention, and that human beings crave sympathy and attention the way they crave water and air? We’ve lived through something like a “vibe shift,” and previously-unchallengeable social justice pieties are increasingly challenged, in good ways and bad. Yet under the broad umbrella of disability rhetoric, it’s always 2018, with both traditional and social media operating under a cloud of fear of giving offense. As I’ve said many times, the number of people who privately agree with me about all this is legion. The number who are willing to say so publicly are very few indeed. Nobody wants to paint that target on their back, I suppose. But why do these issues make people feel like targets at all?