Peter Boettke responds to a New York Times opinion piece by Binyamin Appelbaum, blaming economists for the state of the western world:

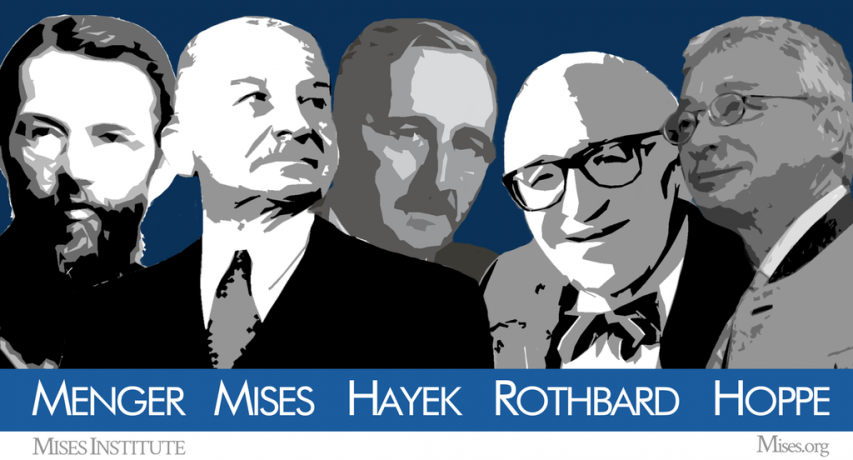

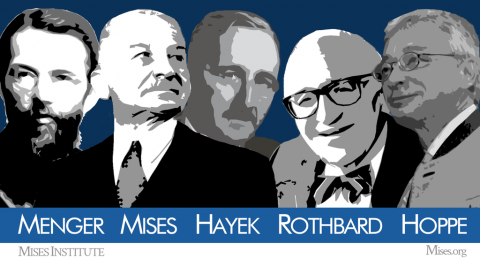

A Mises Institute graphic of some of the key economists in the Austrian tradition (Carl Menger, Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, Murray Rothbard, and Hans-Hermann Hoppe.

Mises Institute via Wikimedia Commons.

But the problem is deeper than economists, it is ANYBODY put in this position of power and prestige, and to do so is fundamentally anti-democratic as was argued by Frank Knight in various writings, and then by Vincent Ostrom in The Intellectual Crisis of American Public Administration, and more recently in David Levy and Sandra Peart’s Escape from Democracy. We cannot fix this problem by replacing one set of “experts” with another set. We have to stop thinking of the relationship between economics and public administration along these lines altogether.

I try to lay out the argument in my SEA address on “Economics and Public Administration“, which also served as an attempt to summarize two decades of research that several of us have undertaken in this spirit. The critical argument in that text for this issue is that I argue that economics is a derived demand, if we conceive of the task of public administration one way, that will shape not only shape the supply and demand of economists, but dictate what it means to produce an economist — and thus, what is means to be an economist.

The problem with narratives like Appelbaum’s isn’t that he is suspicious of the pretensions of economists, it is that he is blaming the wrong culprit for the mess we’re in. Here it is important that everyone of these critics read Gregory Mankiw’s very important piece, published BEFORE the financial crisis, on the macroeconomist as scientists (read Chicago New Classical and Monetarists) and the macroeconomists as engineers (read MIT/Harvard Keynesian and New Keynesians). The Chicago folks — and the Austrian, Virginia, UCLA, etc. folks — did not go to DC, did not write laws, didn’t attempt to orchestrate economic miracles abroad, or stimulate growth at home. They taught, they lectured, the researched and wrote papers in journals and published books, and a subset of them wrote opinion editorials and did interviews in various forms of popular media. In short, they were teachers and students of society. They did not get paid to be experts for the government in general. They were not advisors. But others were — from Keynes to Larry Summers — the line is long. Just look at the number of central bankers that were PhD students under Stan Fischer at MIT. Can you trace that same lineage to Milton Friedman? How about to F. A. Hayek? Mises? Right, I didn’t think so.

“Neo-liberalism” is actually little more than an effort to bring neoclassical models of efficiency into the operation of governmental agencies — that in another era was called “market socialism” — just look at Abba Lerner’s The Economics of Control. He actually thought he had found the right way to combine socialist aspirations with the teachings of economics so he could ensure microeconomic efficiency and macroeconomic stability and provide economists with the tools to successfully steer the economic ship. That basic idea from mid-20th century to today has never disappeared in those halls of power — what has appeared is a waffling between liberal (in the American sense) Keynesianism, and conservative Keynesianism, but Keynesianism exists throughout. The Samuelsonian Neo-classical synthesis achieved the status he hoped for it … and provides the meaning behind his statement in the teachers manual “I don’t care who writes a nation’s laws … if I can write its economics textbooks.” Samuelson knew that if he could wrest control of the tacit presuppositions of public policy functionaries, then there thoughts and actions would be guided by what he taught about market failure, macroeconomic instability, and government as a corrective to our economic woes. It’s an amazing achievement what he did. For at least a generation, perhaps two, he controlled both the introduction to economics market, and the advanced training of PhD students in economics market.

Thinkers rose up in opposition to this hegemony from the older generation such as Knight, Mises and Hayek, but also among his contemporaries such as Alchian, Coase and Friedman, and of course a younger generation such as Becker and Lucas, but also Demsetz, Kirzner, etc. But, look at those names … they did not go to Washington DC to work for domestic policy agencies or the international agencies in economic policy. They were content in their jobs as economic scholars/teachers. They were humble students of society, and some among them rose to the status of social critics and intellectuals. But again none were master manipulators of the organs of power to try to shape the economy into the image of their ideal.