The Province of Ontario is the most populous province in Canada, home to 38.5% of Canada’s national population as of the 2021 census. Located in Central Canada, it is the political, economic, and cultural heart of the country. Its capital, Toronto, is the nation’s largest city and financial centre, while Ottawa, the national capital, lies along Ontario’s eastern edge. Ontario is bordered by Quebec to the east and northeast, Manitoba to the west, Hudson Bay and James Bay to the north, and five U.S. states to the south — Minnesota, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York — mostly along a 2,700 km (1,700 mi) boundary formed by rivers and lakes in the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence drainage system. Though Ontario is the second-largest province by total area after Quebec, the vast majority of its people and arable land are concentrated in the warmer, more developed south, where agriculture and manufacturing dominate. Northern Ontario, in contrast, is colder, heavily forested, and sparsely populated, with mining and forestry serving as the region’s primary industries. But Ontario is more than just a province; it is the crucible of English-speaking Canada.

In 1784, after the American Revolution, Loyalist settlers arrived with intention, bringing with them the legal traditions, religious institutions, and steadfast allegiance to the Crown that had shaped their former world. They sought to uphold a civilisational order rooted in monarchy, Church, and Law, and to establish a society founded on duty, hierarchy, and restraint. From these early Loyalist settlements, beginning at Kingston, a distinct political and cultural tradition emerged. It was neither British nor American. It became the foundation of a new people.

Today, the descendants of these settlers form the core of an ethnocultural identity known as Anglo-Canadian. Numbering over ten million across the country, and more than six million in Ontario, Anglo-Canadians are known for their enduring institutions: constitutional monarchy, common law, Protestant-rooted civic morality, and a national ethos shaped by loyalty and order. This cultural framework shaped Ontario’s development across every sphere of life.

Loyalists built the province’s schools, banks, and legal systems. They established its early industries, including agriculture, forestry, mining, and railroads, and later came to dominate the professional sectors of law, education, public administration, and finance. Their shining city, Toronto the Good, became the centre of Canadian banking and corporate life, while small towns across the province were anchored by courthouses, parish churches, and grain elevators.

Language and schooling played a central role in shaping the Anglo-Canadian character. Ontario’s education system, from common schools to universities, was built to transmit British values, civic order, and the English language. Protestant denominational schools and later public grammar schools taught the children of settlers to read scripture, study British history, and speak in the elite formal register of English Canada. Institutions such as Upper Canada College, Queen’s University, and the University of Toronto became pillars of elite formation, producing the clergy, lawyers, teachers, and administrators who carried the culture forward.

Culturally, Anglo-Canadians preserved a rhythm of domestic and seasonal life rooted in British tradition but adapted to the northern landscape. Autumn fairs, apple bobbing, and harvest suppers marked the calendar in rural communities. Roast beef, butter tarts, mincemeat pies, and tea with milk became the everyday fare of farmhouses and urban kitchens alike. Sunday observance, cenotaph ceremonies, school uniforms, and service clubs reflected a moral seriousness and civic sense inherited from the Loyalist project. It is this tradition that formed the structural spine of its political and cultural development.

Fortissax, “Loyal she Began, Loyal she Remains”, Fortissax is Typing, 2025-07-07.

October 9, 2025

QotD: Ontario and the Loyalists

December 22, 2024

Canada’s founding peoples

Fortissax contrasts Canadians and Americans ethnically, culturally, and historically. Here he discusses Anglo-Canadians and French-Canadians:

To understand Canada, you must first understand its foundations.

Canada is a breakaway society from the United States, like the United States was a breakaway society from the British Empire. You might even argue that Britain represented a thesis, America an antithesis, and Canada the synthesis.

Anglo-Canadians

Anglo-Canadians are descendants of the Loyalists from the American Revolution. They were North Americans, not British transplants, as depicted in American propaganda like Mel Gibson’s The Patriot. They shared the same pioneering and independent spirit as their Patriot counterparts. All were English “Yeoman” or free men. American history from the Mayflower to 1776 is also Canadian history. It is why both nations share Thanksgiving. Some historians have identified the American Revolution as an English civil war, and this is a fairly accurate assessment.

The United States’ founding philosophy was rooted in liberalism; it is a proposition nation based on creed over blood, shaped by Enlightenment thinkers like Edmund Burke and John Locke, now considered “conservative”. American revolutionaries embraced ideals of meritocracy, individualism, property rights, capitalism, free enterprise, republicanism, and democracy, which empowered the emerging middle class.

Anglo-Canada’s founding philosophy is British Toryism, emerging as a traditionalist and reactionary force in direct response to the American Revolution. During the revolution, many Loyalists had their private property seized or redistributed, suffered beatings in the streets, and in the worst cases, faced public executions or the infamous punishment of tar and feathering. Canadian philosopher George Grant, who is considered the father of Anglo-Canadian nationalism, traced their roots to Elizabethan-era Anglican theologian Richard Hooker.

Canada’s motto, Peace, Order, and Good Government (POGG), reflects a philosophy in stark contrast to the American ideal of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Anglo-Canadians valued God, King, and Country, emphasizing public morality, the common good, and Tory virtues like noblesse oblige — the expectation and obligation of elites to act benevolently within an organic hierarchy. While liberty was important, it was never to come at the expense of order. Canadian conservatism before the 1960s was not a variation of liberalism, as in the U.S., but a much older, European, and genuinely traditional ideology focused on community, public order, self-restraint, and loyalty to the state — values embedded in Canada’s founding documents.

Section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867, empowers Parliament to legislate for the “peace, order, and good government” of Canada, giving rise to Crown corporations like Ontario Hydro, the CBC, and Canadian National Railway — state-owned enterprises. Canada’s tradition of mixed economic policies is often misunderstood by Americans as socialism, communism, or totalitarianism. These state-owned enterprises have historical precedents, such as state-controlled factories during Europe’s industrial revolution, often run by landed nobility. Going further back, state-owned mines in ancient Athens and Roman Empire granaries also exemplify this model, which cannot be simplistically labeled as “Islamofascist communism” — a mischaracterization of anything not aligned with liberalism by many Americans, and increasingly many populist Canadians.

It is also a lesser-known historical fact that Canada was almost ennobled into a kingdom rather than a dominion. This idea was suggested by Thomas D’Arcy McGee, a prominent Irish-Canadian politician, journalist, and one of the Fathers of Confederation. Deeply involved in the creation of Canada as a nation, McGee proposed in the 1860s that Canada could be formed as a monarchy with a hereditary nobility, possibly with a viceroyal king, likely a son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He believed this would provide stability and continuity to the fledgling nation. While this idea was not realized, its influence can be seen in the entrenched elites of Canada, who, in a sense, became an unofficial aristocracy.

An element of Canada’s conservative origins can also be found in its use of traditional British and French heraldry. Every province, for example, has a medieval-style coat of arms, often displayed on its flag, which reinforces this connection to the old-world traditions McGee sought to preserve.

McGee’s vision was rooted in his belief in the importance of monarchical institutions and his desire to strengthen Canada’s bond with the British Crown while fostering a distinct Canadian identity. He argued that ennobling Canada would give the country legitimacy and elevate it in the eyes of Europe and the wider world.

French-Canadians

French Canada, with Quebec as its largest and most influential component, has a distinct history shaped by its French colonial roots. Quebec was primarily settled by French colonists, and its unique culture and identity have evolved over the centuries, heavily influenced by Catholicism and monarchical traditions.

The Jesuits and other Catholic organizations played a pivotal role in shaping early French Canadian society. They not only spread Christianity but also laid the foundation for Quebec’s social and cultural identity. The Jesuits, part of the Society of Jesus, were among the first Catholic missionaries to arrive in New France. Invited by Samuel de Champlain, the founder of Quebec, in 1611, they helped convert Indigenous populations to Catholicism but often remained separate from them. By 1625, they had established missions among various Indigenous nations, including the Huron, Algonquin, and Iroquois.

Unlike France, Quebec bypassed the upheavals of the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror. Isolated from the homeland, the Catholic Church in Quebec consolidated its power, and French colonists faced the threat of extinction due to their initially low numbers, particularly during the one-hundred-year war with the Iroquois. This struggle only strengthened their resolve. Over time, this foundation gave rise to Clerico-Nationalism, particularly exemplified by figures like Abbé Lionel Groulx, a theocratic monarchist and ultramontanist influenced by anti-liberal Catholic nationalist movements in France. Groulx and his contemporaries emphasized loyalty to the Pope over secular governments, and their influence was so strong that the Union Nationale government of Maurice Duplessis embodied many of their beliefs.

Attempts to secularize education in the 1860s were thwarted, as the Catholic theocracy shut them down and restored control to the Church. Quebec remained a theocracy well into the 20th century, with the Catholic Church controlling public schooling and provincial healthcare until the 1960s. For much of its history, Quebecois culture saw itself as the last bastion of the traditionalist, Catholic, monarchist Ancien Régime of the fallen Bourbon monarchy. Liberal republicanism and the French Revolution were regarded as abominations, and French-Canadians believed they were the true French.

This mindset persists today, especially regarding Quebecois French. The 400-year-old dialect, rooted in Norman French and royal court French, is still regarded by many French-Canadians as “true French”. However, Europeans often deny this claim, pointing out the influence of anglicisms and the use of joual, a working-class dialect that was deliberately encouraged by Marxist intellectuals and separatists during the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s to proletarianize the population.

November 18, 2024

“The Great Canadian Lie is the claim that we’ve ‘always been multicultural'”

Fortissax thinks that the rest of Canada has lessons to be learned from Quebec:

If you are a Canadian born at any point in the Post-WWII era, you have been subjected to varying degrees of liberal “Cultural Mosaic” propaganda. This narrative exploits the historic presence of three British Isles ethnic groups (which had already been intermixing for millennia) and the predominantly Norman French settlers to justify the unprecedented mass migration of people from the Third World into Canada. This process only began in earnest in the 1990s before accelerating rapidly in the 2010s.

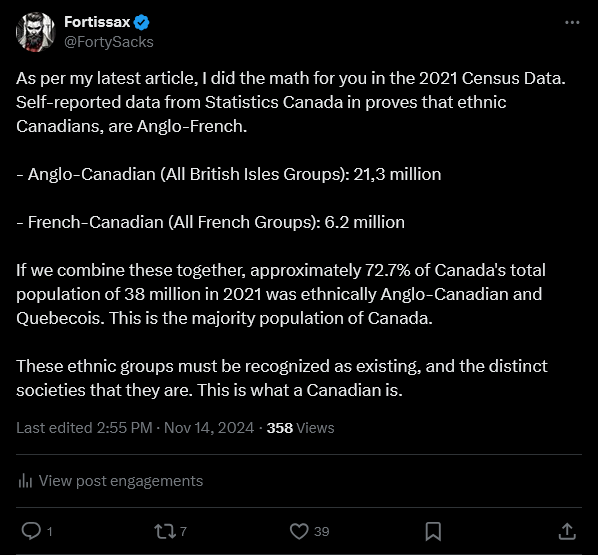

The Great Canadian Lie is the claim that we’ve “always been multicultural”, as though the extremely small and inconsequential presence of “Black Loyalists” or the historically hostile Indigenous groups (making up only 1% of the population at Canada’s founding in 1867) played any serious role in shaping the Canadian nation, its identity, institutions, or culture. Inspired by Dr. Ricardo Duchesne’s book Canada in Decay: Mass Immigration, Diversity, and the Ethnocide of Euro-Canadians (2017), which chronicled the emergence of two ethnic groups uniquely born of the New World, I delved into the 2021 Census data collected by the Canadian government to explore the ethnic breakdown of White Canadians in greater detail

The evidence is clear. In 2021, just four years ago, 72.7% of the entire Canadian population was not just White, but Anglo-Canadian and French-Canadian, representing an overwhelming presence compared to visible minorities and other White ethnic groups, such as the small populations of Germans and Ukrainians.

In the space last night, I highlighted this historical fact and explained to the audience the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Canadian and its significance. While we all recognize that the Québécois are a homogeneous group descended predominantly from Norman French settlers — such as the Filles du Roi and Samuel de Champlain’s 1608 expedition, which established Quebec City with a single-minded purpose — the Anglo-Canadian story also deserves similar recognition for its role in shaping Canada’s identity.

But what is less known is that Anglo-Canadians are just as ethnically homogeneous as the Québécois, from Nova Scotia to British Columbia. Anglo-Canadian identity emerged from Loyalist Americans in the 1750s, beginning with the New England Planters in Nova Scotia — “continentals” with a culture distinct from both England and the emergent Americans. After the American Revolutionary War, they marched north with indomitable purpose, like Aeneas and the Trojans, to rebuild their Dominion. Author Carl Berger, in his influential work The Sense of Power: Studies in the Ideas of Canadian Imperialism, demonstrates that the descendants of Loyalists were the one ethnic group that nurtured “an indigenous British Canadian feeling.” The following passage from Berger’s work is worth citing:

The centennial arrival of the loyalists in Ontario coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the incorporation of the City of Toronto and, during a week filled with various exhibitions, July 3 was set aside as “Loyalist Day”. On the morning of that day the platform erected at the Horticultural Pavilion was crowded with civic and ecclesiastical dignitaries and on one wall hung the old flag presented in 1813 to the York Militia by the ladies of the county. Between stirring orations on the significance of the loyalist legacy, injunctions to remain faithful to their principles, and tirades against the ancient foe, patriotic anthems were sung and nationalist poetry recited. “Rule Britannia” and “If England to Herself Be True” were rendered “in splendid style” and evoked “great enthusiasm”. “A Loyalist Song”, “Loyalist Days”, and “The Maple Leaf Forever”, were all beautifully sung

The 60,000 Loyalist Americans, who arrived in two significant waves, were soon bolstered by mass settlement from the British Isles. However, British settlers assimilated into the Loyalist American culture rather than imposing a British identity on the new Canadians. The first major wave of British settlers after the Loyalists primarily consisted of the Irish. Before Confederation in 1867, approximately 850,000 Irish immigrants settled in Canada. Between 1790 and 1815, an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 settlers, mainly from the Scottish Highlands and Ireland, also made their way to Canada.

Another large-scale migration occurred between 1815 and 1867, bringing approximately 1 million settlers from Britain to Canada, specifically to Ontario, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. New Brunswick was carved out from the larger province of Nova Scotia to make room for the influx of Loyalists. During this time, settlers from England, Scotland, and Ireland intermingled and assimilated into the growing Anglo-Canadian culture. Scottish immigrants, who constituted 10–15% of this wave, primarily spoke Gaelic upon arrival but adopted English as they integrated.

All settlers from the British Isles spoke English (small numbers spoke Gaelic in case of Scots), were ethnically and culturally similar, and had much more in common with each other than with their continental European counterparts.

Settlement would slow down in the years immediately preceding Confederation in 1867 but surged again during the period between 1896 and 1914, with an estimated 1.25 million settlers yet again from Britain moving to Canada as part of internal migration within the British Empire. These settlers predominantly also [went] to Ontario and the Maritimes, further forging the Anglo-Canadian identity.

A common misconception among Canadians is that Canada “was a colony” of Britain, subordinate to, or a “vassal state”. This is wrong. Canadians were the British, in North America. There were no restrictions on what Canadians could or could not do in their own Dominion. From the first wave of Loyalists onward, Canadians were regularly involved in politics and governance, actively participating in shaping the nation.

Like the ethnogenesis of the English, which saw Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and Frisians converge into a new people and ethnicity (the Anglo-Saxons), Anglo-Canadians are a combination of 1.9 million English, 850,000 Irish (from both Northern and Southern Ireland), and 200,000 Scots, converging with 60,000 Loyalist Americans from the 13 Colonies. These distinct yet similar ethnic groups no longer exist as separate peoples in Canada. Anglo-Canadians are the fusion of the entire British Isles. The Arms of Canada, the favourite symbol of Canadian nationalists today, represents this new ethnic group with the inclusion of the French:

It’s no coincidence that, once rediscovered, the Arms of Canada exploded in popularity as the emblem of Canadian nationalists. Unlike more controversial symbols that appeal to pan-White racial unity, such as the Sonnenrad or Celtic cross, the Arms of Canada resonate as a distinctly Canadian icon, deeply rooted in the nation’s true heritage and history — a heritage that cannot be bought, sold, or traded away. This is an immutable bloodline stretching into the ancient past. If culture is downstream from race, and deeper still, ethnicity, then Canadian culture, values, and identity are fundamentally tied not just its race, but its ethnic composition. The ethnos defines the ethos. Canadians are not as receptive to the abstract idea of White nationalism for the same reason Europeans aren’t — because they possess a cohesive ethnic identity, unlike most White Americans.

November 17, 2024

Contrasting origin stories – the 13 Colonies versus the “Peaceful Dominion”

At Postcards From Barsoom, John Carter outlines some of the perceived (and real) differences in the origin stories of the United States and Canada and how they’ve shaped the respective nations’ self-images:

The US had plans to invade Canada that were updated as recently as the 1930s (“War Plan Crimson”, a subset of the larger “War Plan Red” for conflict with the British Empire). Canada also had a plan for conflict with the US, although it fell far short of a full-blooded invasion to conquer the US, designated as “Defence Scheme No. 1”, developed in the early 1920s.

In perennial contrast to its tumultuous southern neighbour, Canada has the reputation of being an extremely boring country.

America’s seeds were planted by grim Puritans seeking a blank slate on which to inscribe the New Jerusalem, and by aristocratic cavaliers who wanted to live the good life while their slaves worked the plantations growing cash crops for the European drug trade. The seeds of America’s hat were planted by fur traders gathering raw materials for funny hats.

America was born in the bloody historical rupture of the Revolutionary War, casting off the yoke of monarchical tyranny in an idealistic struggle for liberty. Canada gained its independence by politely asking mummy dearest if it could be its own country, now, pretty please with some maple syrup on top.

America was split apart in a Civil War that shook the continent, drowning it in an ocean of blood over the question of whether the liberties on which it was founded ought to be extended as a matter of basic principle to the negro. Canada has never had a civil war, just a perennial, passive-aggressive verbal squabble over Quebec sovereignty.1

America’s western expansion was known for its ungovernable violence – cowboys, cattle rustlers, gunslingers, and Indian wars. Canada’s was careful, systematic, and peaceful – disciplined mounties, stout Ukrainian peasants, and equitable Indian treaties.

Once its conquest of the Western frontier was wrapped up, America burst onto the world stage as a vigorous imperial power, snatching islands from the Spanish Empire, crushing Japan and Germany beneath the spurred heel of its cowboy boot, and staring down the Soviet Union in the world’s longest high-stakes game of Texas Hold’Em. Canada, ever dutiful, did some stuff because the British asked nicely, and then they went home to play hockey.

America gave the world jazz music, rock and roll, and hip-hop; Canada contributed Celine Dion and Stan Rogers. America has Hollywood; Canada, the National Film Board and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. America dressed the world in blue jeans and leather jackets; Canadians, flannel and toques. America fattened the people with McDonald’s; Canada burnt their tongues with Tim Horton’s, eh.2

The national stereotypes and mythologies of the preceding paragraphs aren’t deceptive, per se. Stereotypes are always based in reality; national mythologies, as with any successful mythology, need to be true at some level in order to resonate with the nations that they’re intended to knit together. Of course, national mythologies usually leave a few things out, emphasizing or exaggerating some elements at the expense of others in the interests of telling a good story. Revisionists, malcontents, and subversives love to pick at the little blind spots and inconsistencies that result in order to spin their own anti-narratives, intended as a rule to dissolve rather than fortify national cohesion and will. Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States is a good example of this kind of thing, as is Nikole Hannah-Jones’ tendentious 1619 Project.

Probably the most immediately obvious difference between Americans and Canadians is that Americans don’t suffer from a permanent identity crisis. Demographic dilution due to decades of mass immigration notwithstanding, Americans by and large know who they are, implicitly, without having to flagellate themselves with endless introspective navel-gazing about what it means to be an American. The result of this is that most American media isn’t self-consciously “American”; there are exceptions, of course, such as the occasional patriotic war movie, but for the most part the stories Americans tell are just stories about people who happen to be American doing things that happen to be set in America. Except when the characters aren’t American at all, as in a historical epic set in ancient Rome, or aren’t set in America, as in a science fiction or fantasy movie. That basic American self-assurance in their identity means that Americans effortlessly possess the confidence to tell stories that aren’t about America or Americans at all, as a result of which Hollywood quietly swallowed the entire history of the human species … making it all American.

As Rammstein lamented, We’re All Living in Amerika …

Since we’re all living in Amerika, the basic background assumptions of political and cultural reality that we all operate in are American to their very core. Democracy is good, because reasons, and therefore even de facto dictators hold sham elections in order to pretend that they are “presidents” or “prime ministers” and not czars, emperors, kings, or warlords. Insofar as other countries compete with America, it’s by trying to be more American than the Americans: respecting human rights more; having freer markets; making Hollywood movies better than Hollywood can make them; playing heavy metal louder than boys from Houston can play it. It’s America’s world, and we’re all just along for the ride.

America’s hat, by contrast, is absolutely culturally paralyzed by its own self-consciousness … as a paradoxical result of which, its consciousness of itself has been almost obliterated.

Canada’s origin – the origin of Anglo-Canada, that is – was with the United Empire Loyalists who migrated into the harsh country of Upper Canada in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War. As their name implies, they defined themselves by their near-feudal loyalty to the British Crown. Where America was inspired by Enlightenment liberalism, Canada was founded on the basis of tradition and reaction – Canada explicitly rejected liberalism, offering the promise of “peace, order, and good government” in contrast to the American dream of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”.

1. Quebec very nearly left the country in a narrow 1995 referendum in which 49.5% of the province’s population voted to separate. It is widely believed in Anglo Canada that had the rest of the country been able to vote on the issue, Quebec would be its own country now.

2. Well actually a Brazilian investment firm has Timmies, but anyhow.

June 1, 2024

From Sic semper tyrannis to the “Non-Aggression Principle”

On Substack Notes, kulak points out that the beliefs that led to the American colonists taking up arms against King George’s government don’t expire:

A statue idealizing the individual minutemen who would compose the militia of the United States.

Postcard image of French’s Concord Minuteman statue via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the things that drives me nuts about people who claim to subscribe to modern libertarianism (as opposed to the American Revolutionary ideology) is the claim to be “peaceful” and “antiwar”

Libertarianism isn’t antiwar. The American founding values aren’t antiwar. They never have been. It is a permanent declaration of war.

Live Free or Die

Sic Semper Tyrannis.

“Thus always to tyrants”

When does “always” end? NEVER

If those values succeed then 10,000 years from after your descendants have forgotten the name of America itself, they will be killing tyrants and carving their hearts from their chest.

Libertarianism is not “peaceful” it is a declaration that no peace shall ever exist again. That a free people will never have peace with any who’d seek to rule them. Eternal civil war against all would-be tyrants from the pettiest to the most grandiose.

The “non-aggression principle” does not state that the libertarian my never aggress against another … It states only that he may not aggress FIRST, afterwards any and all aggression, even the most disproportionate, is permitted.

“Taxation is Theft” is the claim that a tax collector or government agent paid out of taxes has the same moral status as burglar/home invader caught in your child’s bedroom. It is the claim that that those who benefit and enable the welfare programs paid out of your taxes have the same moral protection from your wrath should you gain the upper hand as a mugger actively threatening you with a gun lest you hand over your wallet.

“Taxation is Theft” necessarily justifies just as revolutionary and total a upset in the political order as “Property is Theft” did … because theft inherently is a violation of your extended person to be resisted without restriction. And just as the Communist claim of “property is theft” justified the most total and brutal wars in human history to destroy the social order (and social classes) who made “property” possible. Libertarianism and “Taxation is Theft” must necessarily justify just as extreme a charnel house to render “Taxation” impossible.

“Live Free or Die” is necessarily, and has always been a declaration of war upon those who would choose not to “live free”, or remain loyal to a tyrant or master.

The founding fathers didn’t make nice with the Loyalists who remained faithful the crown: They ethnically cleansed large portions of them equal to 4% the US population (notably the Loyalist Dutch of New York), confiscated their lands, and drove them into Canada, several mothers with babes nearly starving. Then they invaded them again in 1812. (Read Tigre Dunlop’s interviews with the survivors in Canada in “Recollections on the War of 1812”).

What Loyalists who managed to remain in the US did not regain full rights as citizens until after the war of 1812, almost 40 years after the revolution.

So if you claimed to believe in “Libertarianism” or the American Revolution, ask yourself: “Do I really believe in Liberty and the American Revolution? Or am I a just a flavor of Progressive Democrat who thinks the income tax should be slightly lower?”

Signed,

A Canadian Descended from Loyalists

September 2, 2022

QotD: Historical parallels between the British and American empires

… let us compare the US imperial experience to its British model. A whimsical exercise in comparative dates.

England was colonised by the Norman Empire (a tribe that spread across France, Britain, Italy, and the Middle East can be referred to as an empire I believe), in 1066. After some initial fierce resistance, they settled well, integrated with the local economy, and started developing a more advanced economic society.

North America was colonised by the British Empire (and Spanish and French of course), in the sixteenth century. After some initial fierce resistance, they settled well, integrated with the local economy, and started developing a more advanced economic society.

Norman England spent the next few centuries gradually taking out its neighbours. Wales, Ireland, and eventually Scotland (though the fact that the Scottish King James I & VI actually inherited England confuses this concept a bit). The process was fairly violent.

The North American “English” colonies spent the next few centuries taking out their neighbours. Indian tribes, Dutch, Spanish and French colonists, etc. The process was fairly violent.

England fought a number of wars over peripheral areas, particularly the Hundred Years war over claims to lands in France.

The North American colonies enthusiastically joined (if not blatantly incited) the early world wars, with the desire of taking over nearby French and Spanish colonies

The English fought a civil war in the 1640s to 50s over the issue of how to share power between the executive government, the oligarchs, and the commons. It appears that the oligarchs incited the commons (which was not very common in those days anyway). It was extremely bloody, and those on the periphery — particularly the Scots and Irish — came out badly (and with a long term bad taste for their over-mighty neighbour).

The Colonies fought their first civil war over the issue of how to share power between the executive, the oligarchs and the commons in the 1770s to 80s. It is clear that the oligarchs incited the commons (who in the US were still not very common — every male except those Yellow, Red or Black. An improvement? Certainly not considering the theoretical philosophical base of the so-called Revolution!). It was not really so bloody, but those on the periphery — particularly the Indians and slaves (both of which were pro-British), and the Loyalists and Canadians — came out badly. (60-100,000 “citizens” were expelled or forced to flee for being “loyalists”, let alone Indians and ex-slaves). Naturally the Canadians and their new refugee citizens developed a long term bad taste for their over-mighty neighbour — who attempted to attack them at the drop of a hat thereafter.

The British spent the next century and a half accumulating bits of empire — the Dominions, the Crown Colonies, and the Protectorates — in a haphazard fashion. Usually, but not always, troops followed traders and settlers.

The United States spent the next century and a half accumulating bits of empire — conquests from the Indians, purchases from France and Russia, conquests from Mexico and Spain, annexations of places like Hawaii, etc. — in a haphazard fashion. Usually, but not always, troops followed traders and settlers.

Nigel Davies, “The Empires of Britain and the United States – Toying with Historical Analogy”, rethinking history, 2009-01-10.

July 4, 2018

The War of 1812 on the frontier

Danny Sjursen on what he calls the “Forgotten and Peculiar War of 1812”, specifically the odd situation on the US/Canadian border:

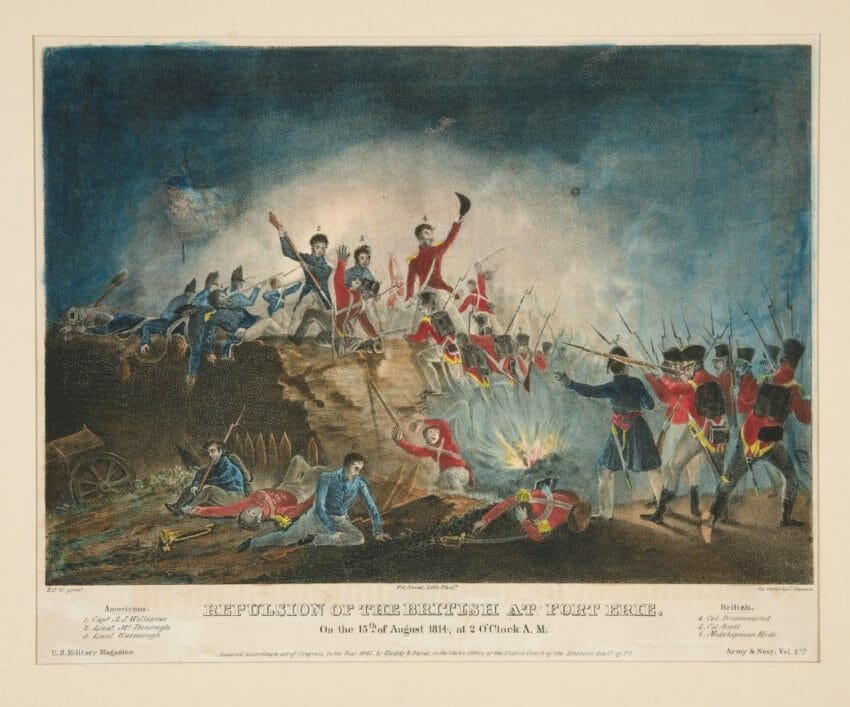

A lithograph based on an E.C. Watmough painting titled “Repulsion of the British at Fort Erie, 15 August 1814.” It depicts an attack that occurred at the U.S.-Canadian border during the War of 1812.

Image via AntiWar.com

“The acquisition of Canada, this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching.” —Thomas Jefferson (1812)

“People speaking the same language, having the same laws, manners and religion, and in all the connections of social intercourse, can never be depended upon as enemies.” —Baron Frederick de Gaugreben, British officer, in 1815

No one seems to know this (or care), but the United States had long coveted Canada. In two sequential wars, the U.S. Army invaded its northern neighbor and intrigued for Canada’s incorporation into the republic deep into the 19th century. Here, on the Canadian front, the conflict most resembled a civil war.

Canada was primarily (though sparsely) populated by two types of people: French Canadians and former American loyalists — refugees from the late Revolutionary War. Some, the “true” loyalists, fled north just after the end of the war for independence. The majority, however, the “late” loyalists, had more recently settled in Upper Canada between 1790 and 1812. Most came because land was cheaper and taxes lower north of the border. Far from being the despotic kingdom of American fantasies, Canada offered a life rather similar to that within the republic. Indeed, this was a war between two of the freest societies on earth. So much for modern political scientists’ notions of a “Democratic Peace Theory” — the belief that two democracies will never engage in war. Britain had a king, certainly, but also had a mixed constitution and one of the world’s more representative political institutions.

In many cases families were divided by the porous American-Canadian border. Loyalties were fluid, and citizens on both sides spoke a common language, practiced a common religion and shared a common culture. Still, if and when an American invasion came, the small body of British regular troops would count on these recent Americans — these “late” loyalists — to rally to the defense of mother Canada.

And came the invasion did. Right at the outset of the war in fact. Though the justification for war was maritime and naval, the conflict opened with a three-pronged American land invasion of Canada. The Americans, for their part, expected the inverse of the British hopes — the “late” loyalists, it was thought, would flock to the American standard and support the invasion. It never happened. Remarkably, a solid base of Canadians fought as militiamen for the British and against the southern invaders. Most, of course, took no side and sought only to be let alone.

It turned out the invading Americans found few friends in Canada and often alienated the locals with their propensity for plundering and military blunder. Though the war raged along the border — primarily near Niagara Falls and Detroit — for nearly three years the American campaign for Canada proved to be an embarrassing fiasco. Defeats piled up, and Canada would emerge from the war firmly in British hands. In the civil war along the border, the Americans were, more often than not, the aggressors and the losers.

[…]

The Treaty of Ghent, which ended the war, changed nothing. There was no change of borders, and the British said nothing about impressment — the purported casus belli! So just what had those thousands died for?

Certainly it was no American victory that forced the British to the peace table. By 1814 the war had become a debacle. Two consecutive American invasions of Canada had been stymied. Napoleon was defeated in April 1814, and the British finally began sending thousands of regular troops across the Atlantic to teach the impetuous Americans a lesson — even burning Washington, D.C., to the ground! (Though in fairness it should be noted that the Americans had earlier done the same to the Canadian capital at York.) The U.S. coastline was blockaded from Long Island to the Gulf of Mexico; despite a few early single ship victories in 1812, the U.S. Navy was all but finished by 1814; the U.S. Treasury was broke and defaulted (for the first time in the nation’s history) on its loans and debt; and 12 percent of U.S. troops had deserted during the war.

The Americans held few victorious cards by the end of 1814, but Britain was exhausted after two decades of war. Besides, they had never meant to reconquer the U.S. in the first place. A status quo treaty that made no concessions to the Americans and preserved the independence of Canada suited London just fine.