Published on 23 Sep 2015

Imagine you take your car in to the shop for routine service and the mechanic says you need a number of repairs. Do you really need them? The mechanic certainly knows more about car repair than you do, but it’s hard to tell whether he’s correct or even telling the truth. You certainly don’t want to pay for repairs you don’t need. Sometimes, when one party has an information advantage, they may have an incentive to exploit the other party. This type of exploitation is called moral hazard, and can happen in many situations — a taxi driver who takes the “long route” to get a higher fare from a tourist, for example. In this video, we cover moral hazard and what is known as the principal-agent problem.

November 16, 2016

Moral Hazard

October 17, 2016

Hillary Clinton tells us to expect a major US recession shortly after January 20, 2017

Fortunately, as Tim Worstall explains, politicians can rarely be believed — especially when it comes to economics:

Hillary Clinton Vows To Slam The Economy Into Recession Immediately Upon Election

This probably isn’t quite what Hillary Clinton intended to say but it is what she did say at a fundraiser on Friday night. That immediately upon election she would slam the US economy into a recession. For what she has said is that she’s not going to add a penny to the national debt. Which, in an economy running a $500 billion and change budget deficit means tax rises and or spending cuts of $500 billion and change immediately she takes the oath. And that’s a large enough and fierce enough change, before she does anything else, to bring back a recession.

[…]

Now, what she meant is something more like this. That she has some spending plans, which she does. And she is also proposing some tax rises. And that her tax rises will balance her spending plans and thus the mixture of plans will not increase the national debt. Which is possibly even true although I don’t believe a word of it myself. For her taxation plans are based upon static analyses when we really must use dynamic ones to measure tax changes. This is normally thought of as something that the right prefers. For if we measure the effects of tax cuts using the dynamic method then there will be some (please note, some, not enough for the cuts to pay for themselves) Laffer Effects meaning that the revenue loss is smaller than that under a static analysis. But this is also true about tax rises. Behaviour really does change when incentives change. Thus tax rises gain less revenue in real life than what a straight line or static analysis predicts.

That is, as I say, probably what she means. But that’s not actually what she said. She said she’ll not add a penny to the national debt. Which means that immediately on taking office she’s got to either raise taxes by $500 billion and change or reduce spending by that amount. Because the budget deficit is that $500 Big Ones and change at present and the deficit is the amount being added to the national debt each year. The problem with this being that that’s also some 3.5% or so of GDP and an immediate fiscal tightening of that amount would put the US economy back into recession.

August 24, 2016

The Tragedy of the Commons

Published on 26 Jun 2015

In this video, we take a look at common goods. Common resources are nonexcludable but rival. For instance, no one can be excluded from fishing for tuna, but they are rival — for every tuna caught, there is one less for everyone else. Nonexcludable but rival resources often lead to what we call a “tragedy of the commons.” In the case of tuna, this means the collapse of the fishing stock. Under a tragedy of the commons, a resource is often overused and under-maintained. Why does this happen? And how can we solve this problem? Like we’ve done so many times throughout this course, let’s take a look at the incentives at play. We also discuss Nobel Prize Winner Elinor Ostrom’s contributions to this topic.

August 18, 2016

QotD: The environmental and economic idiocy of the ethanol mandate

Ever since the beginning of the ethanol mandate it was obvious to anybody with eyes to see that the whole thing was a boondoggle and a huge waste for everybody except ADM. What the Greens failed to understand is that if you prop up corn prices by buying, distilling and burning massive amounts of corn whisky in cars, two things are going to happen. One the price is going to go up, making things like cow feed and other uses of corn more expensive and 2. farmers are going to, without restraint, plant ever larger amounts of corn, which will 1. push out other crops like wheat and 2. require more land use to plant even more corn. Which is why you can now go from Eastern Colorado to Western NY and essentially see nothing but corn. Millions of acres of corn, across the country, grown to burn. Somehow this was supposed to be environmentally friendly?

J.C. Carlton, “The Law Of Unintended Consequences Hits Biofuels”, The Arts Mechanical, 2016-08-07.

July 26, 2016

Craft brewing has a growing trademark problem

At Techdirt, Timothy Geigner predicts that the craft beer market is getting close to trademark armageddon … they’re running out of punny names they can legally use for their beer:

With all the trademark actions we’ve seen taken these past few years that have revolved around the craft beer and distilling industries, it seems like some of the other folks in the mass media are finally picking up on what I’ve been saying for at least three years: the trademark apocalypse is coming for the liquor industries. It’s sort of a strange study in how an industry can evolve, starting as something artisan built on friendly competition and morphing into exactly the kind of legal-heavy, protectionist profit-beast that seems like the very antithesis of the craft brewing concept. And it should also be instructive as to how trademark law, something of the darling of intellectual properties in its intent if not application, can quickly become a major speed bump for what is an otherwise quickly growing market.

All of this appears to have caught the eye of Sara Randazzo, blogging at the Wall Street Journal, who notes that the creatively-named craft beers that have been spewing out of microbreweries across the country may be running out of those creative names.

As today’s Wall Street Journal explores, legal disputes in the beer world are becoming the norm as new craft breweries spring up at a rate of roughly two per day. Trademark lawyers have gotten so used to the beer disputes that they are now turning on each other. Some dozen lawyers are contesting San Diego lawyer Candace Moon’s attempt to trademark the term “Craft Beer Attorney,” which she says she rightfully deserves.

Within the rest of the post, Randazzo highlights one dispute between craft brewers in order to give a sense of just how small these belligerent parties are. It’s a dispute that escaped even my radar, despite what has become something of my “beat” around Techdirt. Three professionals with day jobs decided to make a go at brewing craft beer and named their company Black Ops Brewing, the pun resting upon “hops” used in their beer, while also serving as a nod to their family members that served in the military. Three guys making beer, but the trademark dispute came almost immediately.

The problem is that once you’ve been granted a trademark, you have to defend it early and often or you’ll lose it. This means tiny companies with a couple of trademarked products are pretty much required to lawyer-up and threaten to go nuclear at the faintest hint of an infringement for fear they’ll lose the right that they’ve claimed. The gains from pursuing a possible infringement are usually tiny and the legal costs almost always outweigh any “winnings”, but the risks of not doing so are potentially huge. This is an example of a perverse incentive in law.

June 27, 2016

Compensating Differentials

Published on 7 Apr 2015

Firms have an incentive to increase job safety, because then they can lower wages. In this video, we explore this surprising claim in much greater depth. Bear in mind that wages adjust until jobs requiring a similar level of skill have similar compensation practices. Why do riskier jobs often pay more? Why has job safety increased over the years? How does a firm’s profit motive play a role?

The twisted incentive system for government bureaucrats

At Coyote Blog, Warren Meyer explains why bureaucrats so often make what appear to be incomprehensible decisions and then double-down on the decision despite any irrational, economically destructive, or humanitarian consequences:

I want to take an aside here on incentives. It is almost NEVER the case that an organization has no incentives or performance metrics. Yes, it is frequently the case that they may not have clear written formal metrics and evaluations and incentives. But every organization has informal, unwritten incentives. Sometimes, even when there are written evaluation procedures, these informal incentives dominate.

Within government agencies, I think these informal incentives are what matter. Here are a few of them:

- Don’t ever get caught having not completed some important form or process step or having done some bureaucratic function incorrectly.

- Don’t ever get caught not knowing something you are supposed to know in your job.

- Don’t ever say yes to something (a project, a permit, a program, whatever) that later generates controversy, especially if this controversy gets the attention of your boss’s boss.

- Don’t ever admit a mistake or weakness of any sort to someone outside the organization.

- Don’t ever do or support anything that would cause the agency’s or department’s budget to be cut or headcount to be reduced.

You ever wonder why government agencies say no to everything and make it impossible to do new things? Its not necessarily ideology, it’s their incentives. They get little or no credit for approving something that works out well, but the walls come crashing down on them if they approve something that generates controversy.

So consider the situation of the young twenty-something woman across the desk from me at, say, the US Forest Service. She is probably reasonably bright, but has had absolutely no relevant training from the agency, because a bureaucracy will always prefer to allocate funds so that it has 50 untrained people rather than 40 well-trained people (maintaining headcount size will generally be prioritized over how well the organization performs on its mission). So here is a young person with no training, who is probably completely out of her element because she studied forestry or environment science and desperately wanted to count wolves but now finds herself dumped into a job dealing with contracts for recreation and having to work with — for God sakes — for-profit companies like mine.

One program she has to manage is a moderately technical process for my paying my concession fees in-kind with maintenance services. She has no idea how to do this. So she takes her best guess from materials she has, but that guess is wrong. But she then sticks to that answer and proceeds to defend it like its the Alamo. I know the process backwards and forwards, have run national training sessions on it, have literally hundreds of contract-years of experience on it, but she refuses to acknowledge any suggestion I make that she may be wrong. I coined the term years ago “arrogant ignorance” for this behavior, and I see it all the time.

But on deeper reflection, while it appears to be arrogance, what else could she do given her incentives? She can’t admit she doesn’t know or wasn’t trained (see #2 and #4 above). She can’t acknowledge that I might be able to help her (#4). Having given an answer, she can’t change it (#1).

January 22, 2016

QotD: Non-monetary incentives

… the free market flourishes when everyone, most of the time, refrains from taking advantage of each other’s vulnerability.

Many people, especially college professors, are surprised by how much honesty, reciprocity, and trust exist among those who engage in business. The biggest, most successful corporations in the world, such as Google and Apple, are renown[ed] for how much they trust their employees and how much independence they give them. (There are much smaller companies that do so, too.) A very successful entrepreneur I know told me recently that the key to running a large, profitable business is to treat your employees, suppliers, and customers with respect and like responsible people. It’s just not possible always to be looking over someone’s shoulder.

When you trust people to reciprocate that trust, you’re taking a chance that they may take advantage of you. Such pessimism, however, means your relationships with other people — your suppliers, employees, and customers — will never have a chance to flourish. That’s why it goes against your long-term interests to hunker down and never leave yourself vulnerable to opportunistic behavior.

The incentive to treat people right by following norms of honesty and fair play is non-monetary, but it can make your business prosper. It seems that the best business owners aren’t driven primarily by profit-seeking, although they probably wouldn’t do what they’re doing without earning that profit. No, the incentives they follow often have more to do with knowing that they’ve done things the right way and so deserve all that they’ve earned. (Which is why they can get very upset when a politician says, “If you’ve got a business, you didn’t build that.”) That knowledge is something all the money in the world can’t buy.

Sandy Ikeda, “Incentives 101: Why good intentions fail and passing a law still won’t get it done”, The Freeman, 2014-11-13.

January 15, 2016

The Costs and Benefits of Monopoly

Published on 18 Mar 2015

In this video, we explore the costs and benefits of monopolies. We cover how monopolies and patents breed deadweight loss, market inefficiencies, and corruption. But we also look at what would happen if we eliminated patents for industries with high R&D costs, such as the pharmaceutical industry. Eliminating patents in this case may result in less innovation and, specifically, fewer new drugs being created. We also consider some of the tradeoffs of patents and look at alternative ways to reward research and development such as patent buyouts and using prizes to foster innovation.

January 8, 2016

QotD: Thinking like an economist – incentives matter

A lot of what constitutes “thinking like an economist” involves asking the right questions. Those questions typically involve looking for the incentives people face in a particular situation.

For instance, one response to inflation — a sustained increase in an economy’s general price level — is to think that making it illegal to charge more a fixed amount for any given product would solve the problem. That is, you see an outcome you don’t like, and without understanding why it is the way it is, you try to impose what you think is a better outcome. In the case of price ceilings, the consequence is chronic shortages.

Similarly, a common response to rising residential rents in some cities is to declare, “the rent is too damn high!” (In fact, there’s a political party in New York that actually calls itself The Rent Is Too Damn High Party.) This declaration is usually followed by a demand for regulations that would make it illegal to charge more rent than someone in authority thinks is necessary.

On the other hand, if an economist determines that rents are indeed too high in a district, she will then ask how they got that way. (The all-too-common answer — greed — doesn’t go far, because self-interest is no more a cause of high rents than air is a cause of fire.) In many cases, it’s because the supply of residential property has been artificially restricted — perhaps by building codes, minimum parking requirements, and landlords “warehousing” livable buildings in order to escape existing rent-control policies. Armed with some basic economic principles, she would try to figure out what choices people made that caused rents to rise and why they made those choices.

This is another way of saying that incentives matter.

Sandy Ikeda, “Incentives 101: Why good intentions fail and passing a law still won’t get it done”, The Freeman, 2014-11-13.

November 23, 2015

Minimization of Total Industry Costs of Production

Published on 18 Mar 2015

This section connects several ideas covered in previous videos about the price system and profit maximization. In this video, we begin to understand two basic functions of the Invisible Hand. In competitive markets, the market price (with the help of the Invisible Hand) balances production across firms so that total industry costs are minimized. Competitive markets also connect different industries. By balancing production, the Invisible Hand of the market ensures that the total value of production is maximized across different industries. We’ll use the example of minimizing total costs of corn production, and demonstrate our findings through several charts.

November 20, 2015

Here’s a very disturbing economic issue

At Coyote Blog, Warren Meyer shares his concerns about the constantly increasing regulatory burden of American business:

5-10 years ago, in my small business, I spent my free time, and most of our organization’s training time, on new business initiatives (e.g. growth into new businesses, new out-warding-facing technologies for customers, etc). Over the last five years, all of my time and the organization’s free bandwidth has been spent on regulatory compliance. Obamacare alone has sucked up endless hours and hassles — and continues to do so as we work through arcane reporting requirements. But changing Federal and state OSHA requirements, changing minimum wage and other labor regulations, and numerous changes to state and local legislation have also consumed an inordinate amount of our time. We spent over a year in trial and error just trying to work out how to comply with California meal break law, with each successive approach we took challenged in some court case, forcing us to start over. For next year, we are working to figure out how to comply with the 2015 Obama mandate that all of our salaried managers now have to punch a time clock and get paid hourly.

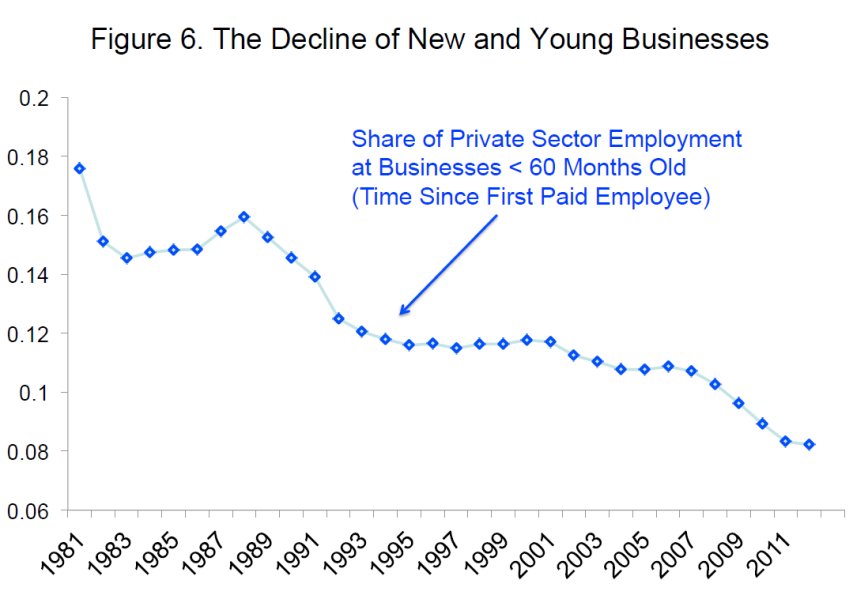

Greg Mankiw points to a nice talk on this topic by Steven Davis. For years I have been saying that one effect of all this regulation is to essentially increase the minimum viable size of any business, because of the fixed compliance costs. A corollary to this rising minimum size hypothesis is that the rate of new business formation is likely dropping, since more and more capital is needed just to overcome the compliance costs before one reaches this rising minimum viable size. The author has a nice chart on this point, which is actually pretty scary. This is probably the best single chart I have seen to illustrate the rise of the corporate state:

November 19, 2015

The historical origins of the nation-state

“Samizdata Illuminatus” on the historical evolution of a bunch of armed thugs into a modern government:

… I was familiar with the hypothesis that the origin of the modern state has its roots in criminal enterprise, yet it is always amusing attempting to reconcile this with the modern state’s increasingly matronly efforts to get its subjects to behave themselves. And it is certainly far from an implausible theory, when you consider how similar the objectives of a criminal enterprise and a state can be. The major difference is, of course, that the state functions within the law — hardly surprising since it is the major source of law — while criminal organisations operate outside of the law. But honestly, how could the activity of a crime gang that defeated a local rival in a turf war be described as anything other than a spot of localised gun control — in terms of ends, if perhaps not means?

But the article got me thinking about what we can do and perhaps intend to do about what Sean Gabb would describe as “the ruling class” — the politicians and senior bureaucrats — but also the minor apparatchiks, too. In terms of the big picture stuff, the bolded part above resonates with me as particularly axiomatic, and if libertarians or classical liberals or small government conservatives or one of the very many labels we choose to call ourselves — if we stand for any one single thing, surely it is for the obliteration of this instinct, this scourge, from the human species. Yes, I am fully aware that previous efforts to change human nature for various ends have generally worked out appallingly, so maybe I should write about ‘disincentivising’ an instinct rather than ‘obliterating’ it. (I’m keeping ‘scourge’. Fair’s fair.) Although there are those amongst us who favour a muscular Ceaușescu solution to big government for those who believe they can spend our hard-earned better than we can, along with those willing to assist them in taking it off us and spending it. Others prefer an incremental strategy of rolling back government to the point that those who wish to “command economic resources” for a living find they enjoy slightly less demand for their services than a VCR repairman. I suspect both methods, perhaps working in concert at times, will be necessary at differing stages of the struggle against the statists if we are ever to be able to declare victory over them (and then leave them alone, as Glenn Reynolds is wont to say).

I do have a gripe about a distinction the author makes between paper-stamping, useless, make-work bureaucracy, and “public goods” bureaucracy, an example of which he doesn’t actually specify, although throughout the piece the inference is quite clear that he’s referring to schools and hospitals and the like — and presumably in the parts of schools and hospitals where service provision takes place; not where the (many) papers are pushed and stamped. Now, many here (rightly, I believe) probably object to the contention made that the market traditionally failed to provide such services of the “public good”, hence the state springing to the rescue to address this “market failure”. There are many people here — Paul Marks comes to mind — who will know a great deal more than I do about the patchwork of friendly societies and other private arrangements that individuals and their families paid into voluntarily and turned to for financial aid in times of illness, unemployment, or other trouble, as well as the nature of the education sector prior to the era of compulsory government schooling; the vast majority of which was crowded out by “free” state healthcare and education. However, my purpose is not wish to dwell on this now, interesting a topic as it is.

October 23, 2015

September 16, 2015

The fate of pedestrians in Chinese traffic accidents

At Gods of the Copybook Headings, Richard Anderson comments on a story about Chinese drivers ensuring that pedestrians they hurt in traffic accidents don’t survive to sue them … because incentives matter:

Smelling a story that was too interesting to be true, I texted a friend who lives in China. He read the article and texted back that every word was correct. This behaviour was so common that it was a kind of dark joke. The phrase “drive to kill” was considered practical life advice for young and old alike. These are not members of some obscure and barbarous cult. China is one of the oldest and most accomplished of human civilizations.

The legal explanation for this — a moral explanation I suspect is impossible — is a combination of a weak insurance system and easily bribable courts. An injured pedestrian can become a lifetime financial liability for the driver. Murder convictions, even in cases with clear video evidence, are still unusual. Faced with a choice of becoming a bankrupt or a murderer the popular choice seems to be the latter.

Homo homini lupus est. Man is wolf to man.

Mainland China is, of course, a dictatorship. It seems likely that in a functioning liberal democracy, such as those of the West, very basic legal reforms would long ago have been implemented to remove these quite literally perverse incentives. The rulers of China have deigned it beneath their notice to make such minor improvements.