Ned Donovan recounts his recent trip to Bhutan, situated in the Himalaya mountains between India and China:

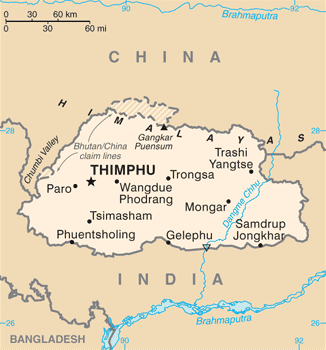

Bhutan map from the CIA World Factbook, 2010. Chinese-disputed border areas are marked with dashed lines and darker shading.

Wikimedia Commons.

Bhutan has long been a place I had wanted to visit, but it isn’t as simple as booking a ticket.

It would be remiss not to quickly situate Bhutan and its history for those unaware. It is a small kingdom east of Nepal and nestled between India and China. It has a population of around 750,000, almost all of whom are devout Buddhists. It was once a land of feuding Tibetan chieftans who were united in the 1630s by a remarkable warrior and Buddhist lama called Ngawang Namgyal. Namgyal died in 1651, but his death was kept a secret from the country for more than 50 years, with officials simply saying that the king was “on an extended retreat” and continued to keep Bhutan together by issuing decrees in his name.

While Namgyal was seen as the spiritual leader, he also established a temporal monarchy which in a slightly modified form still exists today under the leadership of the Wangchuk dynasty. The King of Bhutan’s title is the Druk Gyalpo, which literally translates to Dragon King. Over time Bhutan, being small but strategically located, faded in and out of the spheres of influence of the day from the Mughals to the British Raj. It would have been subsumed into the latter like other princely states, but in the 19th Century a British civil servant placed some files relating to Bhutan into a folder marked “External” instead of “Internal”, a small decision that ensured it remains an independent country today, albeit one “guided” on matters of defence and foreign affairs by a treaty with India.

The country only opened its borders to foreigners in 1974, to mark the coronation of the Fourth King, Jigme Singye Wangchuck. His Majesty saw the opportunity to take advantage of his accession to showcase Bhutan and its unique culture and traditions to the world, but was also aware that unrestricted tourism would put those at risk. Over time, this developed into a vision known as “High Quality, Low Volume” tourism. All visitors must have a guide and driver and also pay a daily fee — currently $100. In 1974, 287 foreigners visited Bhutan, and in 2019 more than 70,000 fee paying tourists came.

As a result of this policy, the trips are largely cultural. You take hikes in unimaginable scenery, watch local festivals where masked creatures tell villagers morality tales, and sit with locals to eat dishes made up mostly of chilis. For fun people relax with the national sport of archery, singing deliciously rude songs to put off their friends while they take shots. Tourists get to have a go but the target is brought closer and you get to use the same kind of bow young children do. Civil servants go to work in traditional dress and robe-clad monks pepper society. In the five days I spent there, much was spent talking to our compulsory guide who was a lovely man named Yarab, who had once been on the Bhutan national football team. One story Yarab told me was that of Bhutan’s transition to democracy.

The previously mentioned Fourth King oversaw Bhutan’s transition into the modern world – but with a catch. Bhutan’s development could not come at the cost of its people’s happiness. Thousands of kilometres of roads were built, free at point of use clinics quickly filled the country, and electricity and telephone hookups turned King Jigme Singye’s isolated kingdom where almost no one had access to healthcare or education into a remarkably healthy and literate little state in the space of just a few decades. Much of the money to make this possible came from selling hydroelectricity generated by dams that are powered by Himalayan glaciers. The Fourth King explained that: “water is to us what oil is to the Arabs”.