In Ontario, many businesses are still struggling to cope with the provincial government’s mandated rise in the minimum wage (the Tim Horton’s franchisees being the current Emmanuel Goldsteins as far as organized labour is concerned). In this essay for the Foundation for Economic Education, Pierre-Guy Veer points out that most franchise businesses have very low profit margins (2.4% for McDonalds franchises, for example) meaning that they can’t just pay the higher wages without a problem, and that the original intent of minimum wage legislation in the US was actually to drive down employment for certain ethnic and racial groups:

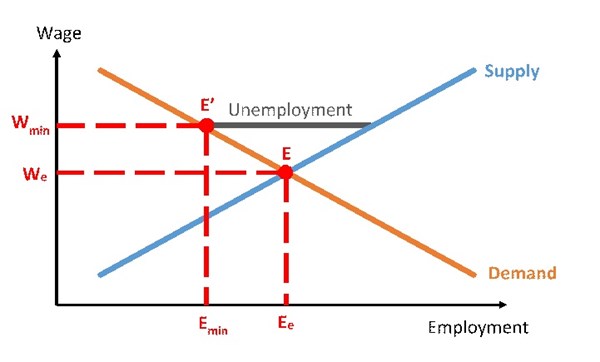

Normally, wages are determined at the intersection of supply (employees offering their services, the blue line) and demand (employers wanting workers, the orange line), the letter E. Since working in retail or restaurants requires little more than a high school diploma, that equilibrium is much lower than, say, a heart surgeon, who must endure years of training and study.

But when governments come and impose a minimum wage (the dark line), wages do increase… at the expense of workers. With a base wage now at E’, more workers want to work but fewer employers want to hire because of the increased cost. The newly formed triangle is made of surplus workers, i.e. unemployed workers who can’t find a job. This unlucky Brian meme summarizes the situation of what minimum wage is: wage eugenics.

And don’t think it’s a vice; creating unemployment was the explicit goal of imposing a minimum wage. It was a Machiavellian scheme imagined during the so-called Progressive Era (late 19th Century to about the 1920s), where it was thought that governments could better humanity by “weeding out” undesirables – in other words, eugenics.

In the U.S., this eugenic attitude was explicitly aimed at African Americans, whose (generally) lower productivity gave them lower wages. To “fight” this problem nationwide, the Hoover administration passed, in 1931, the Davis-Bacon Act in order to impose “prevailing wage” (usually unionized) on all federal contracts. It was a thinly veiled attempt to “weed out” non-unionized workers, who were either African American or immigrant, in order to protect unionized, white jobs. Supporters of the bill, like Representative Clayton Algood, were very explicit in their racist intents:

That contractor has cheap colored labor that he transports, and he puts them in cabins, and it is labor of that sort that is in competition with white labor throughout the country.

But while the racist intent of the minimum wage has disappeared, its effect is always very real. It greatly affects the people it wants to help, i.e. low-skilled workers, and leaves them with fewer options. So don’t be fooled by unemployment statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Youth participation rates (ages 16-19) are still hovering around all-time lows (affected, among others, by minimum wage laws); this means that fewer of them are looking for jobs, decreasing unemployment figures.

It gets worse when breaking down races; only 28.8 percent of African American youth were working or looking for a job, compared to 31.6 for Hispanics and 36.7 percent for whites in December 2017.