I know lots of female professionals — doctors, lawyers, professors, etc. — many of whom are quite good at their jobs. Let’s even, for the sake of argument, stipulate that they’re slightly better than their male colleagues. Leaving aside the thorny (and probably unanswerable) question of just how you’d rank, say, doctors — is strength of schedule a factor? do we trust the coaches’ poll? — the real question is, does society benefit more from a slightly-better, but childless, female MD, or from an excellent stay-at-home mom? Or a pretty-good nurse who works part time while the kids are in school?

Younger folks are no doubt shocked by that question, and if some BCG were ever to read this, she’d try to string me up, but it’s the only question that matters long term. The BCG would start sputtering some question about “what about her happiness?” — the only answer to which, if you want to maintain a stable society, must be: “Category error”. It’s like “staying together for the kids”, another phrase we oldsters recognize, but the younger generation can’t grok. But … but … but … whaddabout your feeeeeelings?

What about them?

Seriously: Who gives a shit? Viddy well, oh my brothers: When you decided to have kids, you didn’t hit the pause button on some video game RPG called “Your Career”; you ejected the disk, snapped that fucker in half, and smashed the Xbox Office Space-style for good measure. What’s good for you, personally, just got sent to the back of the line. Permanently. Yeah yeah, I know, you can’t fulfill your parental obligations if you’re completely miserable all the time, but you can find lots of joy and meaning and yes, even fulfillment (that most insidious of modern weasel words) doing stuff other than making partner down at the law firm.

Men used to understand this, because men were once trained to take the long view, to delay gratification, to suck it the fuck up for the greater good. It’s the same gene — and it IS genetic, 1,000,000+ years of evolution — that causes men to charge bullets or punch kangaroos or do whatever else needs to be done in the face of obvious threats, even at the risk, or even the near certainty, of his own injury or death.

Women don’t roll like that, because they can’t — “that 1,000,000+ years of evolved behavior” thing again. They’re evolved to put the kids first — their kids, not some abstract ideal. Women can be, and often are, suicidally brave — for their own offspring. But absent those — absent the possibility of those — all those maternal instincts go septic, which is how you get the BCG. She knows she’s not cut out for this, no matter how successful she is academically — indeed, in my experience it’s precisely the most academically successful ones who sense it the clearest.

Alas, they are trained that feminism is the answer to those inner alarm bells, so they carry on like caricature cavemen — being as crude and offensive and obnoxious as possible, trying to treat sex like an itch to be scratched while beefing with that basic bitch Becky on the next dorm block.

Severian, “Gettin’ Jiggy in College Town”, Founding Questions, 2021-10-08.

May 9, 2025

QotD: Becoming a parent

September 21, 2024

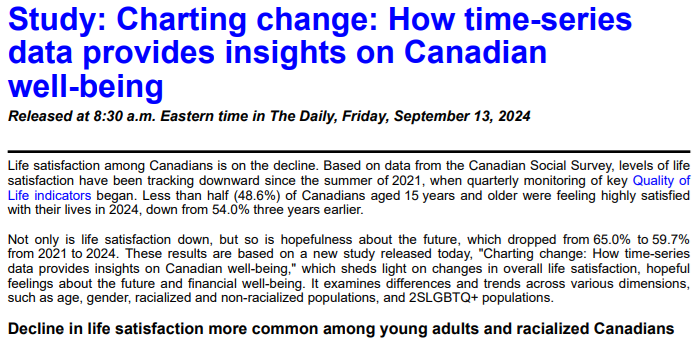

Statistics Canada notes significant decline in life satisfaction and hope for the future

In one sense, we should be quite used to Statistics Canada giving us unwelcome economic news, given the state of the Canadian economy over the last decade. What seems less in character is that they’re connecting the dots between our obvious national financial decline and showing how directly it has impacted ordinary Canadians’ views about life in Canada and what they expect in the future:

Life satisfaction among Canadians is on the decline. Based on data from the Canadian Social Survey, levels of life satisfaction have been tracking downward since the summer of 2021, when quarterly monitoring of key Quality of Life indicators began. Less than half (48.6%) of Canadians aged 15 years and older were feeling highly satisfied with their lives in 2024, down from 54.0% three years earlier.

Not only is life satisfaction down, but so is hopefulness about the future, which dropped from 65.0% to 59.7% from 2021 to 2024. These results are based on a new study released today, “Charting change: How time-series data provides insights on Canadian well-being”, which sheds light on changes in overall life satisfaction, hopeful feelings about the future and financial well-being. It examines differences and trends across various dimensions, such as age, gender, racialized and non-racialized populations, and 2SLGBTQ+ populations.

Decline in life satisfaction more common among young adults and racialized Canadians

Life satisfaction can be considered a pulse check on Canadians’ overall well-being. While this indicator of subjective well-being has been declining for the past few years, there is nonetheless substantive variation in life satisfaction across different demographic groups. Younger adults (aged 25 to 34) had notable declines in their life satisfaction in 2024, with their proportions declining an average of 3.9 percentage points per year since 2021. By 2024, fewer than 4 in 10 (36.9%) of these adults were highly satisfied with their lives.

Meanwhile, seniors (aged 65 and older) maintained their high level of satisfaction, with 61.5% being happy with their lives in 2024. This measure of subjective well-being has remained relatively stable among senior Canadians since 2021.

In addition, racialized Canadians, who are younger on average than non-racialized Canadians, saw greater drops in life satisfaction than their non-racialized counterparts. The proportion of racialized Canadians reporting high levels of life satisfaction fell from 52.7% in 2021 to 40.6% in 2024. This decline was more than five times higher than the decrease observed for non-racialized Canadians, who experienced a decline in life satisfaction of 0.8 percentage points per year from 2021 to 2024. In 2024, over half (51.5%) of non-racialized Canadians were happy with their lives.

It really is a bad sign when the largest province in Confederation is also becoming the most disheartened by its economic prospects:

May 22, 2024

If you re-define it carefully, you can make any statistical measure look hopeful

In his Substack, Tim Worstall jokingly called this piece “Larry Summers Explains Why Americans Hate Joe Biden”:

As a good Democrat of course Larry Summers would never put things in quite that headline way. But the implication of this latest paper with others is to explain why Americans really aren’t as happy as they should be given the economic numbers. The answer being that the economic numbers we all look at to explain how happy folk are aren’t the right economic numbers to explain how happy people are.

We can also make — possibly rightly, possibly wrongly, this might be me projecting more than is merited — a further claim. That Americans simply aren’t as rich as those standard economic numbers suggest either. Which would also neatly explain the general down in the dumps attitude toward the economy.

So, the new paper:

Unemployment is low and inflation is falling, but consumer sentiment remains depressed. This has confounded economists, who historically rely on these two variables to gauge how consumers feel about the economy. We propose that borrowing costs, which have grown at rates they had not reached in decades, do much to explain this gap. The cost of money is not currently included in traditional price indexes, indicating a disconnect between the measures favored by economists and the effective costs borne by consumers. We show that the lows in US consumer sentiment that cannot be explained by unemployment and official inflation are strongly correlated with borrowing costs and consumer credit supply. Concerns over borrowing costs, which have historically tracked the cost of money, are at their highest levels since the Volcker-era. We then develop alternative measures of inflation that include borrowing costs and can account for almost three quarters of the gap in US consumer sentiment in 2023. Global evidence shows that consumer sentiment gaps across countries are also strongly correlated with changes in interest rates. Proposed U.S.-specific factors do not find much supportive evidence abroad.

OK, or as explained by the Telegraph:

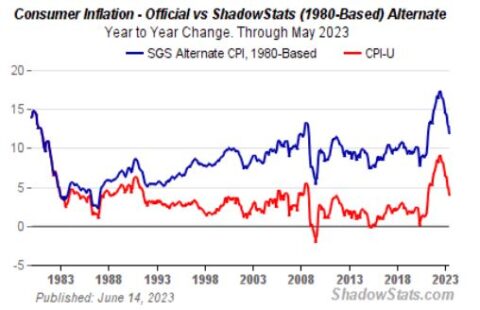

In it, the authors made a shocking claim: if inflation was measured in the same way that it was measured during the last bout of price rises in the 1970s, data showed that it peaked at 18pc in November 2022. This is far higher than the 9.1pc peak inflation shown by the official data.

The reason for this discrepancy is that, since the 1970s, economists have removed the cost of borrowing from the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The motivations here were not nefarious. The reasoning of the statisticians had something to it.

And, OK, if inflation peaked at 18%, not 9%, then that would explain why folk are pissed. Sure it would.

[…]

OK. But that means that if inflation was higher than we’ve been using then the deflation of nominal to real GDP is also wrong. Just that one year of 9% recorded but 18% by this new measure is damn near a 10% difference. That’s how much we’re over-estimating real GDP by right now. Add in a couple of years of lower levels of that and being 20% out wouldn’t surprise.

Which would mean that — if this were true and I might be overegging it — Americans are in fact 20% poorer than the Biden Admin keeps saying they are. And yes, that would piss the voters off, wouldn’t it?

Gaslighting has been a staple of the legacy media for quite some time now, going into high gear during the 2016 US Presidential elections and then into overdrive during the pandemic. They probably don’t even realize they’re doing it any more, because it feels “normal” to them. Yet they wonder why their popularity and public trust in their pronouncements continues to drop.

December 14, 2023

November 17, 2023

QotD: The essential meaninglessness of “happiness” surveys

The reality identified here … is the reason why good economists pay no attention to so-called “happiness studies”. Human wants being unlimited, each and every person – apart from, perhaps, the rare Gandhi – always experiences a vast array of unsatisfied wants. This lack of satisfaction is felt, by many, as a kind of unhappiness – at least as a kind of unhappiness that will strike many people to report it as such on “happiness surveys”.

The good economist understands that ever-greater prosperity does not bring ever-greater felt happiness. But the good economist also understands that people are indeed better off, in a real sense, the higher is their material standard of living. Greater material prosperity brings opportunities to experience new wants, wants that people less prosperous never experience. Inability to satisfy all of these new wants makes many people feel “unhappy”. But were these same people less materially prosperous, they would be at least equally “unhappy” for want of ability to satisfy needs that their current higher level of material prosperity enables them to satisfy.

Another piece of reality revealed by Rogge’s point is that worries about technology or trade destroying opportunities to work are misguided. As long as human beings have unmet desires and unfilled wants, human beings will have opportunities to work.

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2019-08-02.

February 7, 2023

QotD: The misery of certainty

No one else on this earth, I assure you, is so dogmatically certain of anything as ivory tower types are of everything. What they believe today might be 180 degrees from what they believed yesterday, but they still believe it with a fanatical zeal that would make Torquemada blush. Whatever “it” is, it is the capital-T Truth, and they alone possess it …

So why are they always so fucking miserable?

Let’s stipulate, for instance, that gender really is just a social construction. Even if it’s not, you’re dogmatically certain of this. Crucially, everyone else in your world is equally dogmatically certain, so even if it’s not, it is. Shouldn’t you be much, much, much happier? So you’re really a wingless golden-skinned dragonkin. Cool. Everyone else is 100% on board with this. You should be the happiest wingless golden-skinned dragonkin on earth … but you’re not. You’re miserable, and you do your damnedest to make every single other person you come in contact with miserable, too.

As a wise man once put it, if you run into an asshole in the morning, well, you just ran into an asshole. If you run into nothing but assholes all day, then you’re the asshole.

Same question to atheists. I can understand nonbelievers being tormented by their uncertainty, but an atheist is dogmatically certain there’s no god … so why aren’t y’all happier? Why, exactly, does the kid with cancer make you mad? The universe, you’re sure, is nothing but the random collision of atoms. It sucks for the kid that those atoms collided in that particular way, but why are you mad? More to the point, why are you mad? It’s like getting mad at gravity for that apple bonking you on the head. There’s no cosmic injustice without cosmic justice. I’d expect a zenlike calm, but instead, every time I write something about atheism (which I really don’t very often), I get a whole bunch of sour, bitter, angry atheists dropping in to tell me that I’m the asshole.

Severian, “The Emotion is the Tell”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-01-24.

August 7, 2022

You will own nothing … and we don’t care if you like it or not, prole

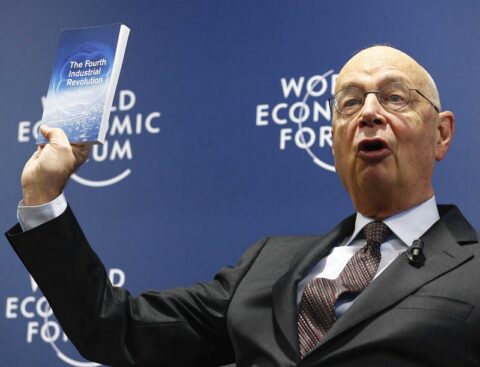

David Solway, reposted at Brian Peckford’s site, gives us a glimpse of the future the Davos crowd want for all us lesser beings:

The much-circulated slogan “You will own nothing, and you will be happy” was coined by Danish MP Ida Auken in 2016 and included in a 2016 essay published by the purveyors of the so-called “Great Reset” at the World Economic Forum (WEF) headquartered in Davos, Switzerland. It is, of course, only half true. Nonetheless, the phrase is certainly apt and should be taken seriously. For once the Great Reset has been put in place, we will indeed own nothing except our compelled compliance.

The world’s farmers and cattle raisers, deprived of their livelihoods on the pretext of reducing nitrogenic fertilizers and livestock-produced methane, will own next to nothing. Meat and grain will become increasingly rare and we will be dining on cricket goulash and mealworm mash, an entomorphagic feast. We will be driving distance-limited electric vehicles rented from the local Commissariat and digitally monitored by Cyber Central — assuming we will still be allowed to drive. Overseen by a cadre of empowered financial managers who can “freeze” our assets at any time, we will possess bank accounts and credit ratings, but they will not be really ours.

Subject to a conceptual misnomer that is nothing but a vacuous abstraction, we will have become “stakeholders” — the WEF’s Klaus Schwab’s favorite word — with no real stake to hold apart from a crutch. In fact, what Schwab’s “stakeholder capitalism” really means, as Andrew Stuttaford explains at Capital Matters, is “transferring the power that capitalism should confer from its owners and into the hands of those who administer it.”

Should the Great Reset ever be fully implemented, we will have been diminished, as Joel Kotkin cogently argues in The Coming of Neo-Feudalism, to the condition of medieval serfs, or reduced to the status of febrile invalids, like those in Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, which, as it happens, was also set in Davos. As Mann ends his novel, addressing his main character Hans Castorp: “Farewell, Hans … Your chances are not good. The wicked dance in which you are caught up will last many a little sinful year yet, and we will not wager much that you will come out whole.”

Modern-day Castorps, we will indeed own nothing, and most assuredly, we will not be happy. As Schwab writes in his co-authored Covid-19: The Great Reset, people will have to accept “limited consumption”, “responsible eating”, and, on the whole, sacrificing “what we do not need” — this latter to be determined by our betters.

What strikes me with considerable force is the pervasive indifference or cultivated ignorance of the general population respecting what the Davos cabal has in store for them. A substantial number of people have never heard of it. Others regard it as just another internet conspiracy — though it is not so much a conspiracy since it is being organized in full sight. The majority of “fact-checkers” and hireling intellectuals wave it away as a right-wing delusion.

December 26, 2021

Repost – The market failure of Christmas

Not to encourage miserliness and general miserability at Christmastime, but here’s a realistic take on the deadweight loss of Christmas gift-giving:

In strict economic terms, the most efficient gift is cold, hard cash, but exchanging equivalent sums of money lacks festive spirit and so people take their chance on the high street. This is where the market fails. Buyers have sub-optimal information about your wants and less incentive than you to maximise utility. They cannot always be sure that you do not already have the gift they have in mind, nor do they know if someone else is planning to give you the same thing. And since the joy is in the giving, they might be more interested in eliciting a fleeting sense of amusement when the present is opened than in providing lasting satisfaction. This is where Billy Bass comes in.

But note the reason for this inefficient spending. Resources are misallocated because one person has to decide what someone else wants without having the knowledge or incentive to spend as carefully as they would if buying for themselves. The market failure of Christmas is therefore an example of what happens when other people spend money on our behalf. The best person to buy things for you is you. Your friends and family might make a decent stab at it. Distant bureaucrats who have never met us — and who are spending other people’s money — perhaps can’t.

So when you open your presents next week and find yourself with another garish tie or an awful bottle of perfume, consider this: If your loved ones don’t know you well enough to make spending choices for you, what chance does the government have?

December 23, 2021

Repost — The lousy economics of gift-giving

Tim Worstall explains why gift-giving at Christmas is so economically inefficient:

The point being made is dual, that individuals have agency and that utility is entirely personal.

To unravel that jargon.

Individuals, peeps, are able to make choices. We delight in making choices in fact, “agency” is the opposite of “anomie”, that feeling that society determines what we may or can do that so depresses the human spirits. We get to choose to get up at 6 am or 8. Have coffee or tea when we do. Go buy the latest platters from the newly popular beat combo, pay the ‘leccie bill or have the coffee out at an emporium.

Having choices, making them, makes people happier.

Secondly, utility. The result of those choices, which of them will maximise happiness, is different for each and every individual. Sure, we can aggregate some of them – food is usually pretty high up everyones’ list, that first litre of water a day tops most. But the higher up Maslow’s Pyramid we go the more tastes – and thus happiness devoured – differ.

So, we make humans happier by their having the choice to do what they want, not what others think they should want or have.

Thus, give people cash at Christmas not socks.

Balancing that is the obvious point that the care and attention with which a present is considered is part of that consumption of happiness. The boyfriend who actually listens to the type of clothing desired and goes gets it provides that joy that a bloke has, for once, been listening. Or the book that would never have been individually considered but was chosen because it might – and does.

Sure.

But the point isn’t about Christmas at all. That’s a way of wrapping the point so it can be left underneath the tree of knowledge.

September 18, 2021

QotD: Material prosperity and happiness

Let me take a moment to agree with all spinmeisters and talking heads, linked in my inbox this morning. Mister Tucker’s monologue on Fox News t’other evening (which I have now “watched” in video and transcript) was a “game-changer”. That is what we (present and former hacks and pandits) call a speech that outclasses the background noise. It makes listeners wonder, however fitfully, whether their sense of current history is right. It “galvanizes” those who, though they agreed with every proposition in advance, ne’er heard them so well expressed. (Gentle reader will find the thing on the Internet soon enough.)

Gallantly, Mister Tucker has articulated the desire of the Right and Left-wavering to raise the tone of American politics to that of Bhutan. His most striking expressions called attention to the fact that material prosperity does not make people happy. Perhaps we should instruct the statisticians to replace their calculations of Gross Domestic Product, with Gross National Happiness, as they now do in Thimphu. The figure would still be meaningless, but might provide some modest, transient uplift.

In my humbly contrary view, material prosperity — i.e. getting filthy rich — does actually make people happy. Those who win the lottery do not cry from despair. But within a few months of scoring, and often within days, they have a new set of personal problems, to pile upon the old ones. Happiness, from material causes, does not last; not even for the poor. It is emotional catharsis. Something makes you happy; and then it fades away.

Only drugs can keep you happy, until you die. But the downside there is that they kill you.

David Warren, “More populist than thou”, Essays in Idleness, 2019-01-04.

August 24, 2021

QotD: Happiness and aging

… our immune system evolved to hum along at peak capacity when we’re happy but to slow down dramatically when we’re not. This is why long-term unhappiness can literally kill you through its immune-suppressing effects, and why loneliness in late adulthood is deadlier than smoking. Indeed, once you’re over sixty-five you’re better off smoking, drinking, or overating with your friends than you are sitting at home alone.

With this background in mind, Trivers hypothesized that older adults evolved a strategy of turning this relationship on its head, becoming more focused on the positive things in life in an effort to enhance their immune functioning. Such a strategy would be more sensible for older than younger adults for two reasons. First, older adults have a weaker immune system than younger adults, and face greater threats from tumors and pathogens. Second, older adults know much more about the world than younger adults do, so they don’t need to pay as much attention to what’s going on around them. For example, when older adults interact with a surly bank employee or a harried flight attendant, they have a library of related experiences to draw upon and can respond to the situation effectively without giving it much thought. As a result, they can afford to gloss over some of the unpleasant things in life.

William von Hippel, The Social Leap: The New Evolutionary Science of Who We Are, Where We Come From, and What Makes Us Happy, 2018.

December 26, 2020

Repost – The market failure of Christmas

Not to encourage miserliness and general miserability at Christmastime, but here’s a realistic take on the deadweight loss of Christmas gift-giving:

In strict economic terms, the most efficient gift is cold, hard cash, but exchanging equivalent sums of money lacks festive spirit and so people take their chance on the high street. This is where the market fails. Buyers have sub-optimal information about your wants and less incentive than you to maximise utility. They cannot always be sure that you do not already have the gift they have in mind, nor do they know if someone else is planning to give you the same thing. And since the joy is in the giving, they might be more interested in eliciting a fleeting sense of amusement when the present is opened than in providing lasting satisfaction. This is where Billy Bass comes in.

But note the reason for this inefficient spending. Resources are misallocated because one person has to decide what someone else wants without having the knowledge or incentive to spend as carefully as they would if buying for themselves. The market failure of Christmas is therefore an example of what happens when other people spend money on our behalf. The best person to buy things for you is you. Your friends and family might make a decent stab at it. Distant bureaucrats who have never met us — and who are spending other people’s money — perhaps can’t.

So when you open your presents next week and find yourself with another garish tie or an awful bottle of perfume, consider this: If your loved ones don’t know you well enough to make spending choices for you, what chance does the government have?

December 24, 2020

Repost — The lousy economics of gift-giving

Tim Worstall explains why gift-giving at Christmas is so economically inefficient:

The point being made is dual, that individuals have agency and that utility is entirely personal.

To unravel that jargon.

Individuals, peeps, are able to make choices. We delight in making choices in fact, “agency” is the opposite of “anomie”, that feeling that society determines what we may or can do that so depresses the human spirits. We get to choose to get up at 6 am or 8. Have coffee or tea when we do. Go buy the latest platters from the newly popular beat combo, pay the ‘leccie bill or have the coffee out at an emporium.

Having choices, making them, makes people happier.

Secondly, utility. The result of those choices, which of them will maximise happiness, is different for each and every individual. Sure, we can aggregate some of them – food is usually pretty high up everyones’ list, that first litre of water a day tops most. But the higher up Maslow’s Pyramid we go the more tastes – and thus happiness devoured – differ.

So, we make humans happier by their having the choice to do what they want, not what others think they should want or have.

Thus, give people cash at Christmas not socks.

Balancing that is the obvious point that the care and attention with which a present is considered is part of that consumption of happiness. The boyfriend who actually listens to the type of clothing desired and goes gets it provides that joy that a bloke has, for once, been listening. Or the book that would never have been individually considered but was chosen because it might – and does.

Sure.

But the point isn’t about Christmas at all. That’s a way of wrapping the point so it can be left underneath the tree of knowledge.

December 25, 2019

Repost – The market failure of Christmas

Not to encourage miserliness and general miserability at Christmastime, but here’s a realistic take on the deadweight loss of Christmas gift-giving:

In strict economic terms, the most efficient gift is cold, hard cash, but exchanging equivalent sums of money lacks festive spirit and so people take their chance on the high street. This is where the market fails. Buyers have sub-optimal information about your wants and less incentive than you to maximise utility. They cannot always be sure that you do not already have the gift they have in mind, nor do they know if someone else is planning to give you the same thing. And since the joy is in the giving, they might be more interested in eliciting a fleeting sense of amusement when the present is opened than in providing lasting satisfaction. This is where Billy Bass comes in.

But note the reason for this inefficient spending. Resources are misallocated because one person has to decide what someone else wants without having the knowledge or incentive to spend as carefully as they would if buying for themselves. The market failure of Christmas is therefore an example of what happens when other people spend money on our behalf. The best person to buy things for you is you. Your friends and family might make a decent stab at it. Distant bureaucrats who have never met us — and who are spending other people’s money — perhaps can’t.

So when you open your presents next week and find yourself with another garish tie or an awful bottle of perfume, consider this: If your loved ones don’t know you well enough to make spending choices for you, what chance does the government have?

December 23, 2019

The lousy economics of gift-giving – “non-cash is a poor receipt of value”

Tim Worstall explains why gift-giving at Christmas is so economically inefficient:

The point being made is dual, that individuals have agency and that utility is entirely personal.

To unravel that jargon.

Individuals, peeps, are able to make choices. We delight in making choices in fact, “agency” is the opposite of “anomie”, that feeling that society determines what we may or can do that so depresses the human spirits. We get to choose to get up at 6 am or 8. Have coffee or tea when we do. Go buy the latest platters from the newly popular beat combo, pay the ‘leccie bill or have the coffee out at an emporium.

Having choices, making them, makes people happier.

Secondly, utility. The result of those choices, which of them will maximise happiness, is different for each and every individual. Sure, we can aggregate some of them – food is usually pretty high up everyones’ list, that first litre of water a day tops most. But the higher up Maslow’s Pyramid we go the more tastes – and thus happiness devoured – differ.

So, we make humans happier by their having the choice to do what they want, not what others think they should want or have.

Thus, give people cash at Christmas not socks.

Balancing that is the obvious point that the care and attention with which a present is considered is part of that consumption of happiness. The boyfriend who actually listens to the type of clothing desired and goes gets it provides that joy that a bloke has, for once, been listening. Or the book that would never have been individually considered but was chosen because it might – and does.

Sure.

But the point isn’t about Christmas at all. That’s a way of wrapping the point so it can be left underneath the tree of knowledge.