Published on 30 Apr 2016

Check out HistoryBuffs review of Lawrence of Arabia: http://bit.ly/NickOfArabia

Big thank you to Nick from History Buffs for this collaboration. It was really fun!

T.E. Lawrence better known as Lawrence of Arabia is one of the biggest legends of World War 1. His adventures in the Middle East during the Arab Revolt were made into a movie and a bestselling book. But how did Lawrence actually end up in Cairo? And what was his relationship with Faisal?

May 1, 2016

T.E. Lawrence And How He Became Lawrence Of Arabia I WHO DID WHAT IN WW1?

March 14, 2016

QotD: The emergence of the historical novel

the historical novel as we know it emerged at the end of the 18th century. The great historians of that age — Hume, Robertson, Gibbon and others — had moved far towards what may be called a scientific study of the past. They tried to base their narratives on established fact, and to connect them through a natural relationship of cause and effect. It was a mighty achievement. At the same time, it turned History from a story book of personal encounters and the occasional miracle to something more abstract. More and more, it did away with the kind of story that you find in Herodotus and Livy and Froissart. As we move into the 19th century, it couldn’t satisfy a growing taste for the quaint and the romantic.

The vacuum was filled by a school of historical novelists with Sir Walter Scott at its head. Though no longer much read, he was a very good novelist. The Bride of Lammermoor is one of his best, but has been overshadowed by the Donizetti opera. I’ve never met anyone else who has read The Heart of Midlothian. But Ivanhoe remains popular, and is still better than any of its adaptations. Whether still read or not, he established all the essential rules of historical fiction. The facts, so far as we can know them, are not to be set aside. They are, however, to be elaborated and folded into a coherent fictional narrative. Take Ivanhoe. King Richard was detained abroad. His brother, John, was a bad regent, and may not have wanted Richard back. There were rich Jews in England, and, rather than fleecing them, as the morality of his age allowed, John tried to flay them. But Ivanhoe and Isaac of York, and the narrative thread that leads to the re-emergence of King Richard at its climax — these are fiction.

I try to respect these conventions in my six Aelric novels. Aelric of England never existed. He didn’t turn up in Rome in 609AD, to uncover and foil a plot that I’d rather not discuss in detail. He didn’t move to Constantinople in 610, and become one of the key players in the revolution that overthrew the tyrant Phocas. He wasn’t the Emperor’s Legate in Alexandria a few years later. He didn’t purify the Empire’s silver coinage, or conceive the land reforms and cuts in taxes and government spending that stabilised the Byzantine Empire for about 400 years. He didn’t lead a pitifully small army into battle against the biggest Persian invasion of the West since Xerxes. He had nothing to do, in extreme old age, with Greek Fire. Priscus existed, and may have been a beastly as I describe him. I find it reasonable that the Emperor Heraclius was not very competent without others to advise him. But the stories are fabrications. They aren’t history. They are entertainment.

Even so, they are underpinned by historical fact. The background is as nearly right as I can make it. I’ve read everything I could find about the age in English and French and Latin and Greek. I’ve read dozens of specialist works, and hundreds of scholarly articles. My Blood of Alexandria is a good introduction to the political and religious state of Egypt on the eve of the Arab invasions. My Curse of Babylon is a good introduction to the Empire as a whole in the early years of the 7th century. The only conscious inaccuracy in all six novels comes in Terror of Constantinople, where I appoint a new Patriarch of Constantinople several months after the actual event. I did this for dramatic effect — among much else, it let me parody Tony Blair’s Diana Funeral reading — but I’ve felt rather bad about it ever since. This aside, any university student who uses me for background to the period that I cover will not be defrauded.

There’s nothing special about this. If you want to know about Rome between Augustus and Nero, the best place to start is the two Claudius novels by Robert Graves. Mary Renault is often as good [as] Grote or Bury on Classical Greece — sometimes better in her descriptions of the moral climate. Gore Vidal’s Julian is first class historical fiction, and also sound biography. Anyone who gets no further than C.S. Forrester and Patrick O’Brien will know the Royal Navy in the age of the French Wars. Mika Waltari is less reliable on the 18th Dynasty in The Egyptian. In mitigation, we know very little about the events and family relationships of the age between Amenhotep III and Horemheb. He wrote a memorable novel despite its boggy underpinning of fact.

I could move from here to talking about bad historical novels. But I won’t. “Judge not, lest ye be judged” is the proper text for anyone like me to bear in mind. What I will do instead is talk about some of the technical difficulties of writing historical fiction. The first is one of balance. If you write a novel about Julius Caesar or Alexander the Great, you start with certain advantages. We all know roughly who these people were. We already have Rex Warner and Robert Graves and Mary Renault. We have all the films and television serials and documentaries. We know that Rome was a collapsing republic before it became an Empire, and that Alexander got as far as India, and died in Babylon. Everyone has heard of Cicero and Aristotle. It’s the same with novels set in the Second World War, or the reign of Elizabeth I. You can give the occasional spot of background, but largely get on with the narrative.

Richard Blake, “Interview with Richard Blake”, 2014-03-14.

March 3, 2016

Theodora – X: This is My Empire – Extra History

Published on 13 Feb 2016

The first recorded outbreak of the Bubonic Plague occurred in Pelusium, an isolated town in the Egyptian province, but soon it moved on to Alexandria. Alexandria was the breadbasket of the Empire, and ships carrying grain (and plague-bearing rats) spread across the Empire. The Plague reached Constantinople to disastrous effect: 25% of the population died. Justinian set up a burial office but even they couldnt keep up with the demand. When they ran out of burial land, they started piling corpses into ships and setting them afloat; they even packed them into the guard towers along the wall. So few people survived that when word got out that Justinian had contracted the plague, hope seemed lost… until Theodora stepped up. She had always been a force within the Empire, Justinian’s co-regent, and now she used that power to fight off the plots against him and keep the Empire together. She dealt ruthlessly with anyone who threatened them, and since many people wanted Belisarius installed on the throne as Justinian’s heir, she recalled him and pushed him out of power. She managed to keep the Empire from disintegrating into Civil War and became the symbol of hope and perserverance for a sorely demoralized city. And then, miraculously, Justinian pulled through.

June 18, 2015

Six Days in June

Published on 23 Feb 2014

Six Day War – Israeli victory – Documentary

The shooting lasted on six tense days in June 1967, but the Six Day War has never really ended. Every crisis that has ripped through this region in the ensuing decades stems from those six fateful days. On its 40th anniversary, the region remains trapped in conflict and is every bit as explosive as it was in 1967. “Six Day War” chronicles the events of forty years ago with a fresh historical perspective. Beginning with the buildup for the war, and the political and military maneuvering of Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol and Egyptian President Jame Adel Nasser, the film takes us through the six days of fighting, the war with Jordan, the occupation of the West Bank and the annexation of Jerusalem. Featuring stunning archival footage and first-hand accounts of the war from both the Israeli and Arab soldiers who fought it, “Six Day War” explores how these events became the flash point in history that reshaped the regional political landscape, destroyed old systems and brought new forces to the fore.

February 6, 2015

Gas! – A New Horror On The Battlefield I THE GREAT WAR Week 28

Published on 5 Feb 2015

After more than 6 months of stalemate, the German Empire is playing two new cards to gain a decisive advantage. On the Eastern Front, the Germans use gas on a huge scale for the first time. While the attack fails, the foundation for gas warfare is laid. At the same time Kaiser Wilhelm II agrees to unrestricted submarine warfare – any ship can be sank at any time.

January 18, 2015

The [f]utility of mass demonstrations

David Warren had a short essay get out of hand on him the other day:

Everything is coming out of Egypt these days, just like in the Bible. The Paris demonstrations were a throwback not only to the grand gatherings of a century ago, when the masses in each European capital were demanding war, but also to the recent “Arab spring,” when the masses in Egypt and every Middle Eastern capital were demanding “democracy.” Mobs often get what they want. The best that can be said for the Jesuischarlies, is they haven’t a clew what they want, beyond making an emotional display of their own vaunted goodness.

And yet, large demonstrations are expressions of despair. They bring momentary relief in a false exhilaration: the idea that something can be done, by men; something that will not cost them vastly more than they are now paying. Verily, it is the counsel of despair. I don’t think I can provide any example from history in which mass political demonstrations did any good; only examples when they did not end as badly as they could have.

I hardly expect agreement on this point, especially on non-violent demonstrations that affirm some simple moral point, such as the wrongness of racial prejudice, or of the slaughter of unborn children. But these must necessarily politicize something which should be above politics, and cannot help bringing an element of intimidation into what must finally be communicated cor ad cor. Pressure politics change everything, such that even when the cause is indisputably elevated — the American civil rights marches of the 1960s are a good example — the effect is dubious. What came out in that case was not simply the destruction of an evil, but its replacement with new evils: welfare provisions which undermined the black family, the poison of race quotas and “reverse discrimination,” the canting and excuse-making and radical posturing that has wreaked more aggregate damage to black people — both spiritual and material — than the wicked humiliations they suffered before. (Read Thomas Sowell.)

“Be careful what you wish for.” Be mindful of what comes with that wish. Be careful whom you ask to deliver it.

December 9, 2014

Exodus: Gods and Kings gets panned by Forbes

Scott Mendelson reviews the soon-to-open movie by Ridley Scott, and finds it awful:

Exodus: Gods and Kings is a terrible film. It is a badly acted and badly written melodrama that takes what should be a passionate and emotionally wrenching story and drains it of all life and all dramatic interest. It hits all the major points, like checking off boxes on a list, yet tells its tale at an arms-length reserve with paper-thin characters. It is arguably a film intended for adults, with violence that makes a mockery of its PG-13 rating, yet it has far less nuance, emotional impact, and moral shading than DreamWorks Animation’s PG-rated and seemingly kid-targeted The Prince of Egypt.

The film starts with an arbitrary mass battle scene, one which serves no purpose save for having a mass battle sequence to toss into the trailers. The primary alteration to the story is the inclusion of said gratuitous action beats. The film is relentlessly grim yet oddly unemotional, which is a tricky balance to accidentally pull off. The actors (who have all done excellent work elsewhere) are all oddly miscast, and that’s not even getting to the whole “really white actors playing Egyptians” thing. Oh right, that little issue… It’s actually worse than you’ve heard.

In retrospect, it may have been better to just make a 100% white cast similar to Noah. This film instead is filled with minorities in subservient roles, be it slaves, servants, or (implied) palace sex toys. Instead of merely having a film filled with only white actors, what the film does is implicitly impose a racially-based class system, where the white characters are prestigious and/or important while the various minorities are inherently second or third-class citizens almost by virtue of their skin color. I am sure this was unintentional, but that’s the visual picture that Exodus paints.

Now to be absolutely fair, even if Exodus was cast with 100% racial/ethnic authenticity, it would still be a pretty bad motion picture. The screenplay has our poor, miscast actors speaking in various accents and in a bizarre hybrid of “ancient times period piece” English and more modern American English, which leads to lines like “From an economic standpoint alone, what you’re asking is problematic,” which is Rameses’s (Joel Edgerton) response to Moses’s initial plea to “Let my people go!”

October 22, 2014

QotD: Ancient history

New interests and different locations are provided by an iPad app that gathers pages relevant to my interests, and lets me indulge particular subjects, like “Ancient History.” This gives me the impression I am learning something, and perhaps I am, but when you finish an article about Xobar the Cruel who ruled during the Middle Period of the Crinchothian Empire (140 square miles in modern-day Herzo-Slavbonia) you think “well, there’s something of which I was previously unaware, and let’s preen for a second about being the sort of person who cares about ancient history,” and then it’s all forgotten. It’s all the history of rulers, which means the history of cruelty, and the remnants of settlements, which means the history of floors and walls and tombs. I fault myself for not having a better grasp on the shadowy beginnings of civilization; it doesn’t snap into focus until the Greeks, and then you’re surprised because they have shoes and religion and government and traditions and the rest of the recognizable pillars that hold up the ceiling mankind builds to put some space between himself and the raging caprices of the gods above. Except for Egypt, where they were doing stuff for a long time, but it was weird.

James Lileks, The Bleat, 2014-04-01

July 23, 2014

The Yom Kippur War of October 1973

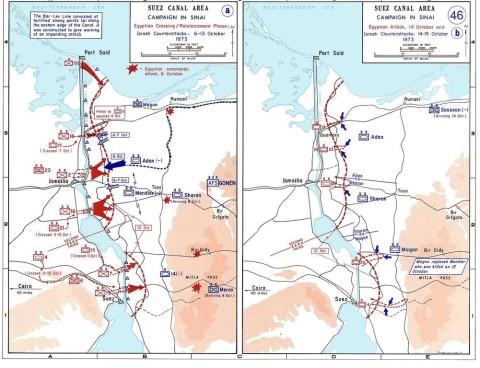

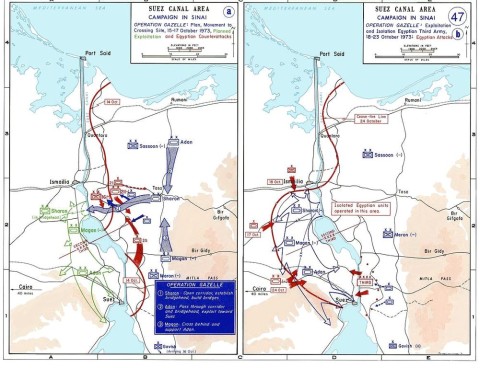

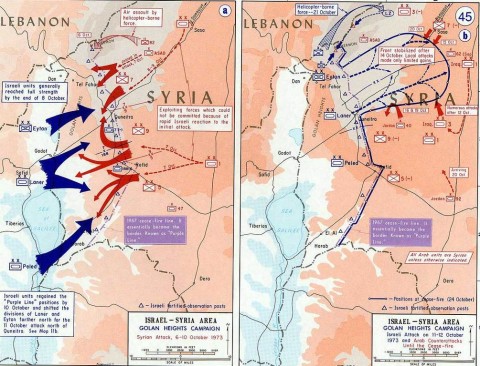

In History Today, Colin Shindler reviews a recent collection of essays on the initially successful surprise attack on Israeli forces by Egypt, Syria, and a token brigade from Jordan in early October, 1973.

During the early afternoon of October 6th, 1973 the Egyptian army crossed the Suez Canal and overran the Israeli Bar-Lev line on the eastern bank. This assault on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, was designed to reverse Israel’s conquest of the Sinai peninsula during the 1967 Six Day War.

Six hundred Syrian tanks, outnumbering Israel’s 178, also advanced to reclaim the Golan Heights and to threaten a penetration of Israel’s heartland. The mehdal (blunder) indicated a profound intelligence failure and cost 2,691 Israeli lives. Forty years on, Asaf Siniver has gathered his colleagues to dissect this war in a series of essays.

The October or Ramadan War – as it is known in Egypt – is celebrated as a holiday even though Arab losses were around 18,000. The Yom Kippur war – as it is known in Israel – is regarded more as an enforced stalemate, even though Israeli forces crossed back over the canal, encircled the Egyptian Third Army and were 60 miles from Cairo. The Syrians, too, were pushed back and the Israelis shelled the outer suburbs of Damascus. Soviet threats to involve the USSR directly in the conflict forced President Nixon to stop the Israelis in their tracks.

Yom Kippur War – Sinai front 6-15 October, 1973 (via Wikipedia)

Yom Kippur War – Sinai front 15-23 October, 1973 (via Wikipedia)

Yom Kippur War – Golan Heights front (via Wikipedia)

February 9, 2014

Democracy and the media

Nigel Davies looks at the uncritical admiration of the form of democracy (while actively ignoring the actual practice) among Western media people:

It is interesting to look around the world at the moment and identify the failures of democracy, and to be amused by the Western media’s complete incomprehension of what is going on and why.

Time and time again you get headlines about how people should stand back and accept the ‘democratically elected government’, despite the fact that the democratic result was a fairly evil dictator keen on persecution, mass murder, civil war and ethnic cleansing.

This is because most ignorant Western journalists believe as an absolute truth that ‘democracy’ is a good thing, despite all the evidence that democracy is as bad, or even worse, than any other form of government. (Interestingly many non-western journalists treat democracy with considerable scepticism, which baffles Western journalists even more.)

Just to be clear Robespiere, Napoleon III, Mussolini and Adolf Hitler were in some form ‘democratically elected’ leaders, and every Communist dictator, ever, has regularly received about 97% of the popular vote in their countries.

[…]

Which brings us to unofficial one party states, like South Africa, where there is a popular vote which means virtually nothing. People get a say, but there is no chance of removing the party which — very largely through its dreadful economic and social policies — has kept the vast majority of the voters ignorant and poor (while flooding them with propaganda suggesting that result is an outside conspiracy, and only the people’s party can save them …) Actually some of you might recognise this more directly as being Mugabe’s very blunt approach, but the principal is the same when adopted by more weasely worded one party statists (for whom too many Western journalists have a romanticised and highly inaccurate perspective).

Most African (and many Asian and Middle Eastern … and Eastern European) ‘nations’ that pretend to democracy, are effectively one party states where the ‘opposition’ is never really going to be allowed to get anywhere.

A current example he points to is Egypt:

I am not just talking about people like Hitler who managed to manipulate 25-30% of the vote to dominate a chaotic parliament long enough to change all the rules and entrench their power. (Though that appears to be the default result for 90-95% of all Republics throughout all history, so perhaps it is worthy of some reflection.) No, I am more interested in places where a genuine majority of the population vote repeatedly for a leader who every educated and thinking (not the same thing unfortunately) person knows will lead them to disaster.

Effectively what we are talking about here is popularistic appeals to the ignorant peasantry who make up the majority of the population.

Egypt recently elected the Muslim Brotherhood. This was done by the majority votes of the ignorant peasants in the rural areas, and against the wishes of practically anyone who could be classed as educated, literate, liberal, or with an understanding of rule of law, or role of commerce and legal rights in a modern society. Ie: the traditional appeal to the ignorant to grab control of the ‘means of production’ and ‘distribute it more fairly’ — which always leads to the same results of poverty and persecution whether you call it a Fascist state (Nazi Germany) Communist state (People’s Republic), Theocratic state (Muslim republic, Hindu republic, North Korea), or just a kleptocracy.

Naturally the Western journalists believe the Muslim Brotherhood should be left to develop its ‘democratic’ course.

The inevitable result of letting the Muslim Brotherhood rewrite the constitution and entrench their powers while introducing a Muslim republic with proper Sharia laws, would be a particularly nasty form of dictatorship. Like Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia, future votes would have been ‘controlled’ and eventually pointless. So the intervention of the military to throw them out and try and redo the democratic project was necessary, and possibly the only (very slim) hope of making it work. However, like Fiji, it may be only the start of many interventions to stop backsliding, until the military and people give up in disgust and settle down to exactly the sort of dictatorship which, more or less, kept things together and slowly moving forward under their previous dictators.

December 24, 2013

Brendan O’Neill on how to become a cause célèbre

It may sound rather cynical, but it does seem to capture the essential elements:

Yesterday, as the world cheered the release of two members of the punk band Pussy Riot from prison in Russia, 450 members of the Muslim Brotherhood went on hunger strike in jails in Egypt. These political prisoners, whose ‘crimes’ include supporting deposed President Mohamed Morsi and taking part in protests calling for his reinstatement, have received rather less global sympathy than Pussy Riot. Even when, last month, 14 women and seven girls were sentenced to 11 years’ imprisonment in Egypt for taking part in an unauthorised pro-Morsi protest, still there was little global outrage. The women and girls (whose punishment has since been reduced to a one-year suspended sentence) were not emblazoned on trendy Westerners’ t-shirts; Madonna didn’t demand their release; Amnesty didn’t pump vast amounts of its resources into calling for their sentences to be squashed, as it has done with Pussy Riot, who have been its main campaigning priority over the past year.

So what does it take for political prisoners to become a cause célèbre among influential Westerners? How can political prisoners overseas win the attention and flattery of human-rights groups, celebs and the concerned commentariat? Here’s an invaluable guide for any locked-up man or woman of conscience who craves the support of human-rights activists.

August 20, 2013

The odd pre-history of the Statue of Liberty

B.K. Marcus on what schoolchildren don’t learn about the famous New York city landmark:

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi wanted wealth and world renown for building a celebrated colossus, and he was willing to shop the idea around — even to the era’s most illiberal customers.

His first pitch for a giant, torch-bearing statue was to the Ottoman viceroy of Egypt, which was, at the time, the single greatest commercial conduit for the international slave trade.

The statue that now stands in New York Harbor is officially called “Liberty Enlightening the World” (La Liberté éclairant le monde). The statue in Egypt was to be called “Egypt Enlightening the World” or, more awkwardly, “Progress Carrying the Light to Asia.”

Failing to close the deal in Egypt, Bartholdi repackaged it for America.

When this bit of backstory reached the American public, Bartholdi denied that one project had anything to do with the other, but the similarity in designs is unmistakable.

Egypt was a vassal state of an authoritarian empire and the gateway for the colossal African slave trade into Asia — whereas the fundraising for the Statue of Liberty proposed a monument not merely to liberty but to the recent abolition of American slavery. (Picture the broken chains at the Statue of Liberty’s feet.)

The original statue was to be an Egyptian woman — a fellah, or native peasant — draped in a burqa, one outstretched arm holding a torch to guide the ships on the great waterway over which she would stand.

Bartholdi had wanted to place his piece at the northern entrance to the Suez Canal in Port Said because the canal represented French greatness in general and engineering greatness more specifically. His statue was to be a synthesis of French art and French engineering, as well as a political symbol of the progress that France offered the East.

The canal was indeed a great engineering accomplishment and a giant step forward for world trade and greater wealth and comfort for everyone — including the toiling masses. But it was built on the back of slave labor, a 10-year corvée that forced Egyptian peasants to do the digging. Thousands died.

August 15, 2013

Egyptian military empowered by Western approval

Brendan O’Neill says that we should not be surprised by the bloody turn of events in Egypt … after all, we collectively acted as enablers:

There is ‘world outcry’ over the behaviour of the Egyptian security forces yesterday, when at least 525 supporters of the deposed Muslim Brotherhood president Mohamed Morsi were massacred. The killings were ‘excessive’, says Amnesty, in a bid to bag the prize for understatement of the year; ‘brutal’, say various handwringing newspaper editorials; ‘too much’, complain Western politicians.

Such belated expressions of synthetic sorrow are not only too little, too late (hundreds of Egyptians have already been massacred by the military regime that swept Morsi from power); they are also extraordinarily blinkered. To focus on the actions of the security forces alone, on what they did with their trigger fingers yesterday, is to miss the bigger picture; it is to overlook the question of where the military regime got the moral authority to clamp down on its critics so violently in the name of preserving its undemocratic grip on power. It got it from the West, including from so-called Western liberals and human-rights activists. The moral ammunition for yesterday’s massacres was provided by the very politicians and campaigners now crying crocodile tears over the sight of hundreds of dead Egyptians.

The fact that General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the head of the Egyptian armed forces who swept Morsi from power on 3 July, feels he has free rein to preserve his coup-won rule against all-comers isn’t surprising. After all, his undemocratic regime has received the blessing of various high-ranking Western officials, even after it carried out massacres of protesters campaigning for the reinstatement of Morsi, who was elected with 52 per cent of the vote in 2012.

Baroness Catherine Ashton, the European Union’s chief of foreign affairs, who, like al-Sisi, is unelected, visited Egypt at the end of July. She met with al-Sisi and his handpicked, unelected president, Adly Mansour. She called on this junta disguised as a transitional power to start a ‘journey [towards] a stable, prosperous and democratic Egypt’. This was after it had massacred hundreds of protesters, placed various politicians and activists in prison, and reinstated the Mubarak-era secret police to wage a ‘war on terror’ against MB supporters. For Ashton to visit al-Sisi and talk about democracy in the aftermath of such authoritarian clampdowns was implicitly to confer authority on the coup that brought him to power and on his brutal rule and actions.

Meanwhile, the US has refused to call the military’s sweeping aside of Morsi a coup. The Democratic secretary of state, John Kerry, has gone further and congratulated al-Sisi’s regime for ‘restoring democracy’. Kerry said the military’s assumption of power was an attempt to avoid ‘descendance into chaos and violence’ under Morsi, and its appointment of civilians in the top political jobs was a clear sign that it was devoted to ‘restoring democracy’. He said this on 2 August. After hundreds of Morsi supporters had already been massacred. If al-Sisi’s forces believe that killing protesters demanding the reinstatement of a democratically elected prime minister is itself a democratic act, a necessary and even good thing, it isn’t hard to see where they got the idea from.

July 9, 2013

Narcissistic Policy Disorder on parade

Greg Weiner looks at the full-blown Narcissistic Policy Disorder of Senator John McCain:

The recently published fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual contains no diagnosis for Narcissistic Polity Disorder — the book’s scope being confined to the personality disorder of a similar name — but should the editors ever wish to expand into political science, they will find an excellent case study in the interview Senator John McCain gave on CBS’ Face the Nation last Sunday. It turns out the Egyptian coup, which gave all signs of being a conflict among Egyptians about Egypt, was in fact about — well, us.

[. . .]

Sectarian violence in the Middle East, an ancient and evidently incurable phenomenon, an American failure? That’s one powerful reflection staring back from the water. It is also a powerful fantasy, with roots in the same place — and the metaphor is separated from reality by only the narrowest of margins — as narcissistic personality disorder, one of whose hallmarks is the proclivity to interpret foreign events in terms of oneself. Any event, anywhere, anytime becomes a test of American leadership: He who does what America wished he had not done had no autonomous motives; he meant to stick a thumb in the American eye.

Thus McCain’s understanding of leadership and its breathtaking condescension — in, ironically, the name of the neoconservative project of spreading freedom. Note that within that model — someone is going to lead and it is therefore best for it to be a, make that the, righteous nation — little room is left for the very thing McCain claims he wants to promote: nations actually making choices about their own futures from within. In the present case, Egyptians are fighting about Egypt; the real issue, according to McCain, must be what the United States had to say, or failed to say, about it. The generals could not possibly have been motivated by (a) different aspirations for Egypt, (b) venality, (c) power or (d) some combination of the above: We must understand their motives for the coup in terms of whether they complied with our request that they “not do that.”

July 4, 2013

Egypt’s new post-Morsi era

Daniel Pipes sees joy in the aftermath of Morsi’s removal from power, but also worry. Lots of worry:

The overthrow of Mohamed Morsi in Egypt delights and worries me.

Delight is easy to explain. What appears to have been the largest political demonstration in history uprooted the arrogant Islamists of Egypt who ruled with near-total disregard for anything other than consolidating their own power. Islamism, the drive to apply a medieval Islamic law and the only vibrant radical utopian movement in the world today, experienced an unprecedented repudiation. Egyptians showed an inspiring spirit.

If it took 18 days to overthrow Husni Mubarak in 2011, just four were needed to overthrow Morsi this past week. The number of deaths commensurately went down from about 850 to 40. Western governments (notably the Obama administration) thinking they had sided with history by helping the Muslim Brotherhood regime found themselves appropriately embarrassed.

My worry is more complex. The historical record shows that the thrall of radical utopianism endures until calamity sets in. On paper, fascism and communism sound appealing; only the realities of Hitler and Stalin discredited and marginalized these movements.

In the case of Islamism, this same process has already begun; indeed, the revulsion started with much less destruction wrought than in the prior two cases (Islamism not yet having killed tens of millions) and with greater speed (years, not decades). Recent weeks have seen three rejections of Islamist rule in a row, what with the Gezi Park-inspired demonstrations across Turkey, a resounding victory by the least-hardline Islamist in the Iranian elections on June 14, and now the unprecedentedly massive refutation of the Muslim Brotherhood in public squares along the Nile River.

But I fear that the quick military removal of the Muslim Brotherhood government will exonerate Islamists.