[The near-perfect formulaic general’s speech before battle] has a few basic parts: I) an opening that focuses on the valor of the men rather than the impact of the speech (the common trope here is to note how “brave men require few words”) II) a description of the dangers arrayed against them, III) the profits to be gained by victory and the dire consequences of defeat IV) the basis on which the general pins his hope of success and finally V) a moving peroration; the big emotional conclusion of the speech. You can read through Catiline’s speech yourself; it’s not long and it follows the formula precisely. That order of elements is not rigid; they can be moved around and emphasis shifted. But I don’t just want to show that this trope existed in the ancient past, I want to show that it is projected through military tradition to the present. So let’s look at another very standard and somewhat more recent example, appropriate for June:

Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force!

You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other Fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle-hardened. He will fight savagely.

But this is the year 1944! Much has happened since the Nazi triumphs of 1940-1. The United Nations have inflicted upon the Germans great defeats, in open battle, man to man. Our air offensive has seriously reduced their strength in the air and their capacity to wage war on the ground. Our Home Fronts have given us an overwhelming superiority in weapons and munitions of war, and placed at our disposal great reserves of trained fighting men. The tide has turned! The free men of the world are marching together to Victory!

I have full confidence in your courage, devotion to duty and skill in battle. We will accept nothing less than full Victory!

Good Luck! And let us all beseech the blessing of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking.

Dwight D. Eisenhower, June 6th, 1944

I’ve highlighted an image of the signed document itself to show the various components of the ancient battle speech (following my numbering above): [https://acoupdotblog.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/breaking-down-the-speech.png?w=689]

Apart from a slight alteration of the order, it is not hard to assign this speech to the same genre as Sallust’s Catiline speech or even Thucydides’ speeches at Delium (Thuc. 4.92-95). As we’ll see, it is certainly not the case that there is no other way to structure a pre-battle exhortation (although, I should note that the standard text of the other famous pre-D-Day General’s speech, Patton’s speech to the Third Army, hits the same notes, but with more words – mostly profanity). But this is the standard structure of a battle speech in the Western literary canon, and speeches with this standard structure, or variations of it, appear frequently.

I think a reader might particularly be caught by the emphasis on a section stressing how formidable the enemy is and how great the danger is (“He will fight savagely”). That seems an odd thing to stress! But it is an important part of the structure of these speeches; it is almost never left out. When paired with the general’s own cause for hope, acknowledging the fearsome nature of the enemy and the general terror of battle is a way to inoculate the soldiers against the seizing fear of battle. The Greeks saw the fear of battle as two distinct elements, deimos (δεῖμος) – the creeping dread before a battle, and phobos (φόβος) – the sudden paralyzing panic in combat, the sharp fear that causes men to flee. If the encouragement of the speech (and the general’s presence) is meant to defuse deimos, openly discussing the fearfulness of the enemy (but couching it in terms of how it may be overcome) is meant to rob phobos of his sting. You do your soldiers no favors by concealing from them the terror they will experience regardless.

Now the bulk of Eisenhower’s D-Day order is dedicated to the fourth part, stating the ground for encouragement, generally framed by the reasons the general is confident despite how fearsome the enemy is. One form of encouragement is a recounting of the noble deeds of the soldiers themselves. One of the marks of good generalship for the Romans was if a general could go up and down the line, calling out individual soldiers and reminding them of great deeds they had performed (Caesar does this, for instance; note Catiline’s opponent, Marcus Petreius encourages his soldiers this way, calling out each one – his is an army of veterans – by name, 59.4). Alternately – especially for a fairly green army where no one has done any great deeds yet – the general might stress the great valor of their forefathers, or the honor of their city or state. The emotion being touched here is pretty clearly pride, tapping into a desire not to let one’s self, one’s community or one’s comrades down. That’s an effective rhetorical tactic; as we’ve discussed, the fear of shame is an effective combat motivator (where so many other motivations fail). Appealing to pride is a good way to arouse that fear of shame, as the two emotions are deeply connected. Alternately, a general may not a superiority in numbers, materiel, tactical position; he may discuss his battle-plan and how it is likely to bring victory. For forces defending on their own ground, the home-field advantage may be stressed.

You want to understand the “fearsome enemy” motif and the “grounds for encouragement” motif working best as a pair.

Consider it this way: you are about to take a very important test. If I, having already taken the test, tell you “oh, don’t worry, the test is easy,” that will help dispel your dread (deimos) before it, but when you sit down with the test paper and read the (quite difficult) questions, the seizing fear (phobos) hits you, and your overall performance is reduced. That seizing panic clouds your thoughts and costs you vital time; in a battle, it might cause you to flee or get you killed. But if I tell you “the test is hard, but (you’ve studied effectively/you can pick up points on XYZ section/etc.)” it not only diminishes the dread before the test, but serves to mentally prepare you for the shock of seeing the real thing. Indeed, I turn your fearful mind into my friend – when the real thing fails to live up to your worst nightmares, you’ll draw confidence from that. When the test turns out to be exactly like I said, the encouragement carries more weight because of the reliability of the warning. I am not dispelling your fear – because this is battle and everyone is afraid and no words can take that away – I am mentally preparing you for your fear. There’s an element of CBT in this: validate the emotion, suggest more helpful ways to think about it, and direct the mind towards behavioral solutions.

Finally, I think it is worth noting what is not generally here. While the speaker is likely to reflect on glorious deeds of the soldiers, or other soldiers like them, or their ancestors, there is generally not a focus on how fearsome or scary or strong they are because no one feels scary or strong when they are terrified. “You’ve done this before” is a good line (so is “our people have always beaten their people”) but “Remember, we are lions” is not. No one feels like a lion when they are receiving indirect fire and cannot fire back; no one feels like a lion when their buddy just went down next to them and there’s nothing they can do about it. Remember: the purpose of the speech isn’t to pump someone up before the charge, it is to emotionally prepare them for the moment when the emotional momentum of the charge is spent and the fear of death comes crashing in to replace it.

Likewise, while “the cause” often figures into such speeches, it does so as a subordinate element; some kind of group membership – the nation, the polis, the legion, comrades-in-arms – is often more prominent (note how Eisenhower’s speech crafts concentric circles of groups that the listener belongs to, watching and depending on the listener; “liberty-loving people everywhere” -> “the United Nations” and “our Allies” -> “our homefront” -> finally “us” and “we”). While it took until the late 1940s for group-cohesion-theory to really emerge on its own, these sorts of speeches show an awareness of what seems to be a timeless truth: the cause may get you to the battle, but only comrades will hold you in it when the dying starts (on this, note especially J. McPherson, For Cause and Comrades (1997)).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Battle of Helm’s Deep, Part VII: Hanging by a Thread”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-06-12.

June 6, 2022

QotD: Eisenhower’s D-Day speech to the troops

May 8, 2022

Kilroy was Here! The fall of Tunis – WW2 – 193 – May 7, 1943

World War Two

Published 7 May 2022Tunis falls to the Allies, but the Axis are still fighting back from their little corner of Tunisia. There is more of the seemingly endless fighting in the Kuban in the Caucasus, and the Chinese Theater comes to life with a new Japanese offensive.

(more…)

May 5, 2022

The Forgotten Battle: The story of the Battle for the Scheldt

Omroep Zeeland

Published 18 Mar 2020Documentary directed by Margot Schotel Omroep Zeeland (2019) about the battle of the Scheldt. An large and important battle in the autumn of 1944, which was crucial for the liberation of the Netherlands and Europe

After D-Day (6 June, 1944), the Allied Forces quickly conquered the north of France and Belgium. Already on 4 September they took Antwerp, a strategically vital harbor. However, the river Scheldt, the harbor’s supply route, was still in German hands. Montgomery was ordered by Eisenhower to secure both sides of the Scheldt, the larger part of which is located in the Netherlands, but Montogomery decided otherwise and started Operation Market Garden. He left the conquest of the Scheldt to the Canadians and the Polish Armies who then had to fight a much stronger enemy that was ordered by Hitler himself to keep its position at all costs. Even though Market Garden eventually failed, it received an almost mythological status in the narrative about the World War II, while the successful battle for the Scheldt was never really acknowledged by history.

With the cooperation of Tobias van Gent, Ingrid Baraitre, Carla Rus, Johan van Doorn ea.

Blijf op de hoogte van het laatste Zeeuwse nieuws:

Volg ons via:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/omroepzeeland/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/omroepzeeland

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/c/omroepzeeland

June 12, 2021

Normandy – 1944 | Movietone Moment | 11 June 2021

British Movietone

Published 11 Jun 2021On this day in 1944, five days after the D-Day landing, the allied forces converged in Normandy. Here is a British Movietone report covering the event.

More and more reinforcements and supplies arrive in Normandy each day. In the skies Allied air power continues to bomb and strafe the enemy. Captured German film shows Rommel and von Rundstedt visiting the vast concrete fortifications on the coast which were thought to be impassable. Mr Churchill arrived onboard HMS Kelvin and was greeted by General Montgomery as he came ashore.

Cut story – Dusk or dawn shot of destroyer with sun rising or sinking in background. Sunrise with armada in fore. Yanks board LCIs. Shots of LCTs. Beached equipment unloaded. GV of activity on beach. British troops of LTC. CU Tedder on bridge of ship. GS of Ramsay & Vian. Tedder, Ramsay & Vian walk along raft into camera. Elevated shot of activity on beach, very good. Troops build airstrip, bulldozers etc. at work. Plane takes off. Camera gun – shooting up trains, transport, & other targets, several large explosions. British pass through street, Frenchmen look on. AFU – British soldiers at look-out with field glasses. Troops (Canadian or British) run through fields & wooded country. Troops through street, French clap. Army transport passes through street, directed by soldier. Yanks march through streets. POW along roads, & over beach, wade out to LCT, one attempts to pull up sock while walking. Captured German reel GS of Rommel & Rundstedt. CU Rommel. SCU of coastal guns, & various shots of fortifications, pillboxes etc. Rommel & Rundstedt walk round inspecting same, look at double barrel coastal gun. SCU of barrel of guns, & various shots of Atlantic Wall (AFU British troops knock part of “Wall” down which they have captured). Eisenhower, Marshall & Arnold on bridge of ship. GV of destroyer Kelvin at sea – very good. CU Churchill in Trinity House uniform, wearing glasses. Churchill assists Brooke with “Mae West” life jackets. Both seated on deck Kelvin at sea. CU Churchill. Kelvin passes Nelson, Ramillies & other warships also large part of armada. Churchill transfers … ships, sailors cheer as he leaves. CU Churchill. CU Smuts both very good. Churchill, Smuts & Brooke in “Duck” [DUKW]. Churchill leans over side talks to Montgomery, Churchill alights from “Duck”. Shakes hands with Monty. The above four in group on beach, walk through crowds of soldiers. AFU – Monty stands on raised platform addresses troops (silent) Monty & Churchill through crowds. Churchill with Monty & climbs into Jeep. SEE STORY NUMBER 44914/2 & 44914/3 FOR CUTS

AP Has HD copy – HD ProRes 422 4:3 – 24fpsDisclaimer: British Movietone is an historical collection. Any views and expressions within either the video or metadata of the collection are reproduced for historical accuracy and do not represent the opinions or editorial policies of the Associated Press.

You can license this footage for commercial use through AP Archive – the story number bm44914

#Normandy #WWII #DDay

Find out more about AP Archive: http://www.aparchive.com/HowWeWork

Twitter: https://twitter.com/AP_Archive

Tumblr: https://aparchives.tumblr.com/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/APNews/

April 7, 2021

QotD: The G-[pick-a-number] meetings

There are far too many of these “summits,” far too undistinguishedly attended, expensive to organize, and conducted in public in ways that attract swarms of hooligans who vandalize shops, beat up bystanders, and provoke the police. Canada spent $400 million on three days of photo-ops at La Malbaie, to achieve practically nothing. For the first nearly 30 years of summiting, there were only nine such meetings; Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin at Tehran and Yalta (1943 and 1945), Stalin, Truman and Attlee at Potsdam (1945), Eisenhower and the divided Russians and Anthony Eden and Edgar Faure at Geneva (1955), Eisenhower, Khrushchev, Macmillan and de Gaulle at Paris (1960), Kennedy and Khrushchev at Vienna (1961), Lyndon Johnson and Alexei Kosygin at Glassboro (1967), and Richard Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev at Moscow and San Clemente, Calif. (1972, 1973).

The first three were essential to plan for victory and peace, though many of their key provisions, especially for the liberation of Eastern Europe, were ignored by Stalin. The first Nixon-Brezhnev meeting was substantive and a couple of the later Reagan-Gorbachev meetings were very productive. These were intense business meetings between people who really were at the summit of world power and influence. The only matter agreed to in meetings between Soviet and American leaders between 1945 and 1972 was in the “kitchen debate” between then vice-president Nixon and Khrushchev in Moscow in 1959, when (forgive my coarseness in the interests of historical accuracy), Khrushchev accused Nixon of uttering “Horse shit, no, it is cow shit, and nothing is fouler than that” to which Nixon replied, “You don’t recognize the truth, and incidentally, pig shit is fouler than cow shit.” Khrushchev conceded the second point.

Conrad Black, “Take heed Canada: the U.S. would win a true trade war”, Conrad Black, 2018-06-16.

September 10, 2020

Is The War Ending? – Oil Crisis and UN Intervention | The Suez Crisis | Part 3

TimeGhost History

Published 9 Sep 2020As Israel nears victory in Operation Kadesh, Britain and France are fighting a losing war of their own on the frontlines of the global political scene. The UN are staunchly against Britain and France’s involvement, and if the duo aren’t careful, another superpower may soon enter the fray, one with the intention of a war of more than just words.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Francis van Berkel

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Francis van Berkel

Image Research: Shaun Harrison & Daniel Weiss

Edited by: Daniel Weiss

Sound design: Marek Kamiński

Maps: Ryan WeatherbyColorizations:

– Mikolaj Uchman

– Daniel Weiss – https://www.facebook.com/The-Yankee-C…

– Carlos Ortega Pereira (BlauColorizations) – https://www.instagram.com/blaucolorizations

– Norman Stewart – https://oldtimesincolor.blogspot.com/

– Jaris Almazani (Artistic Man) – https://instagram.com/artistic.manSources:

National Archives NARA

Images from the UN News and Media

1960s Soviet Film “Egypt our Arab Ally”From the Noun Project:

– Letter by Bonegolem

– soldier by Wonmo Kang

– Oil Tank by MangsaabguruSoundtracks from Epidemic Sound:

– “Devil’s Disgrace” – Deskant

– “As the Rivers Collapse” – Deskant

– “Invocation” – Deskant

– “Call of Muezzin” – Sight of Wonders

– “Crying Winds” – Deskant

– “On the Edge of Change” – Brightarm Orchestra

– “Where Kings Walk” – Jon Sumner

– “Divine Serpent” – Deskant

– “Synchrotron” – Guy Copeland

– “Dunes of Despair” – DeskantArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

2 days ago

We took a long time to settle on a title for this episode because so much happens. Nasser promises a people’s war; the entirety of Western Europe faces an oil crisis; America looks like it might sanction its allies; Israel almost calls the whole thing off; the first-ever international Peacekeeping Force is proposed at the UN; the list goes on. Complicated stuff but this is why our realtime format is so important. Something as crazy as the Suez Crisis can only be adequately understood if you go through it step-by-step. Otherwise, it just becomes an incomprehensible mass of information.Want to ensure we can carry on doing stuff like this? Join the TimeGhost Army https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

August 14, 2020

QotD: Eisenhower and Churchill

From the outset the neophyte American commander understood perfectly well that he was being thoroughly scrutinized, and that to permit himself to be overpowered by the prime minister’s aggressive personality and charm would be disastrous. During 1942 Eisenhower won over Churchill and a warm and enduring friendship developed between the two men that survived some bruising encounters.

Their common love of history became a bond. Churchill was happiest when discussing history and its lessons, and in Eisenhower he found not only a worthy companion but also one of the few who could match him. Once while dining at Chequers, Churchill “remarked to Eisenhower that he had studied every campaisgn since the Punic Wars,” leading Commander Thompson to whisper to his neighbour, “And he’s taken part in most of them!”

Carlo d’Este, Warlord: A life of Winston Churchill at war, 1874-1945, 2008.

May 1, 2020

Federal Express runaway train incident 67 years later

Thunderbolt 1000 Siren Productions

Published 17 Jan 20202 days late and I lost several hours of sleep but holy hell it’s worth it now that it’s done! Enjoy this pretty interesting story on a runaway GG1 just days before Eisenhower’s inaguration

Please don’t shoot me for the Trump pics 😐

Next to come up is Glendale and *passes out*Please donate!

https://www.gofundme.com/thunderbolt-…I’m just a struggling college student! Your generous donations will enable me to continue my education and ensure future posts and educational films. Thank you!!!

Discord server: https://discord.gg/Tqwr4RV

Patron:

https://www.patreon.com/Thunderbolt1000Deviantart: https://www.deviantart.com/pennsy

May 7, 2019

The Suez Crisis reconsidered

Jordan Chandler Hirsch reviews a new book on what is now a somewhat forgotten international crisis that shook the Atlantic alliance, Philip Zelikow’s Suez Deconstructed:

Zelikow encourages readers to assess Suez by examining three kinds of judgments made by the statesmen during the crisis: value judgments (“What do we care about?”), reality judgments (“What is really going on?”), and action judgments (“What can we do about it?”). Asking these questions, Zelikow argues, is the best means of evaluating the protagonists. Through this structure, Suez Deconstructed hopes to provide “a personal sense, even a checklist, of matters to consider” when confronting questions of statecraft.

The book begins this task by describing the world of 1956. The Cold War’s impermeable borders had not yet solidified, and the superpowers sought the favor of the so-called Third World. Among non-aligned nations, Cold War ideology mattered less than anti-colonialism. In the Middle East, its champion was Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who wielded influence by exploiting several festering regional disputes. He rhetorically — and, the French suspected, materially — supported the Algerian revolt against French rule. He competed with Iraq, Egypt’s pro-British and anti-communist rival. He threatened to destroy the State of Israel. And through Egypt ran the Suez Canal, which Europe depended on for oil.

Egypt’s conflict with Israel precipitated the Suez crisis. In September 1955, Nasser struck a stunning and mammoth arms deal with the Soviet Union. The infusion of weaponry threatened Israel’s strategic superiority, undermined Iraq, and vaulted the Soviet Union into the Middle East. From that point forward, Zelikow argues, the question for all the countries in the crisis (aside from Egypt, of course) became “What to do next about Nasser?”

Israel responded with dread, while, Britain, France, and the United States alternated between confrontation and conciliation. Eventually, the United States abandoned Nasser, but he doubled down by nationalizing the Suez Canal. This was too much for France. Hoping to unseat Nasser to halt Egyptian aid to Algeria, it concocted a plan with Israel and, eventually, Britain for Israel to invade Egypt and for British and French troops to seize the Canal Zone on the pretense of separating Israeli and Egyptian forces. The attack began just before the upcoming U.S. presidential election and alongside a revolution in Hungary that triggered a Soviet invasion. The book highlights the Eisenhower administration’s anger at the tripartite plot. Despite having turned on Nasser, Eisenhower seethed at not having been told about the assault, bitterly opposed it, and threatened to ruin the British and French economies by withholding oil shipments.

Throughout, Suez Deconstructed disorients. As the story crisscrosses from terror raids into Israel to covert summits in French villas, from Turtle Bay to the Suez Canal, names and places, thoughts and actions blur. Venerable policymakers scramble to comprehend the latest maneuvers as they struggle with the weight of history: Was Suez another Munich? Could Britain and France still project power abroad? Would a young Israel survive?

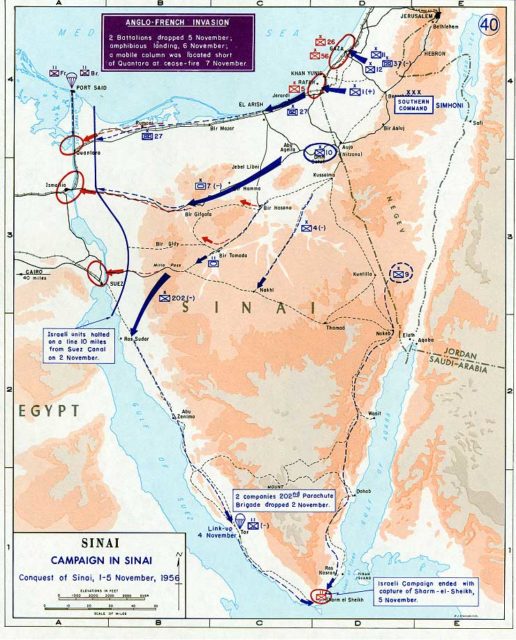

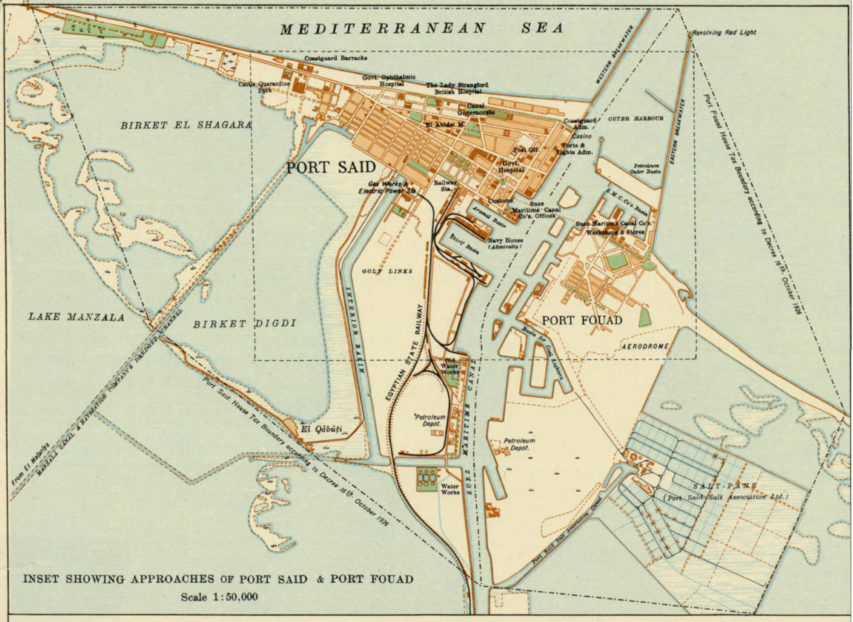

If you’re not familiar with the Suez Crisis and want more than just the Wikipedia article for background, here’s the coverage of the military side of things from the British perspective (Operation Musketeer) from Naval History Homepage.

January 14, 2019

QotD: Eisenhower’s Middle East policy about-face

Unlike some American presidents, however, Eisenhower learned from his mistakes. In 1958, five years after being sworn into office, he reversed course. Rather than suck up to Egypt, Ike deployed American Marines to Lebanon to shore up President Camille Chamoun, who was under siege by Nasser’s local allies.

“In Lebanon,” Eisenhower wrote in his memoirs, “the question was whether it would be better to incur the deep resentment of nearly all of the Arab world (and some of the rest of the Free World) and in doing so risk general war with the Soviet Union or to do something worse — which was to do nothing.” That is almost verbatim what the British said to justify their own war against Nasser when Eisenhower slapped them with crippling sanctions.

Reality forced the United States into a total about-face. Ike’s entire Middle Eastern worldview collapsed. Even before sending the Marines to Lebanon he announced that America was taking Britain’s place as the pre-eminent power in the Middle East. He had to start over even if he didn’t want to. “Nasser,” Doran writes, “the giant who rose from the Suez Crisis, crushed Eisenhower’s doctrine like a cigarette under his shoe.”

What happened between the Suez Crisis and Eisenhower’s intervention in Lebanon? A couple of things.

Ike’s hope to bring Syria into the American orbit alongside Turkey and Pakistan collapsed in spectacular fashion. So many Syrians swooned over Nasser after Egypt’s victory in the Suez Canal that Syria, astonishingly, allowed itself to be annexed by Cairo. Egypt and Syria became one country—the United Arab Republic—with Nasser as the dictator of both.

Washington’s attempt to groom Saudi Arabia as a regional counterbalance to Egypt also hit the skids when Nasser accused the Saudis of trying to assassinate him and foment a military coup in Damascus. The Saudis responded by shoving King Saud aside and replacing him with his Nasserist younger brother, Crown Prince Faisal.

The final blow came with the brutal overthrow of the pro-Western Hashemite monarchy in Iraq and the mutilation of the royal family’s corpses in public, thus toppling the last pillar of America’s anti-Soviet alliance in the Middle East. Eisenhower had no choice but to stop being clever and return to the first rule of foreign policy: reward your friends and punish your enemies.

Michael J. Totten, “We Are Still Living With Eisenhower’s Biggest Mistake”, The Tower Magazine, 2017-02.

January 5, 2019

QotD: Nasser’s anti-American success, funded by the USA

If you’re familiar with the history of the region, you already know that Nasser aligned Egypt with the Soviet Union anyway and whipped up the Arab world into an anti-American frenzy. Ike’s gamble failed. Nasser’s heart was with Moscow all along. He cleverly used Eisenhower as a tool for his own ambitions and planned to stab the United States in the front from the very beginning.

One of Nasser’s deceptions should be familiar to anyone who has followed the painful ins and outs of botched Arab-Israeli peacemaking. Over and over again, Nasser used a strategy Doran calls “dangle and delay.” He repeatedly dangled the tantalizing idea of peace between Egypt and Israel in front of Eisenhower’s eyes, only to delay moving forward for one bogus reason after another. He never planned to make peace with Israel or even to engage in serious talks.

Nasser did, however, participate in theatrical arms negotiations with Washington that he knew would never go anywhere.

Eisenhower wanted to equip the Egyptian army. Nasser wasn’t stupid, though. He knew that Ike would attach strings to the deal. Egypt’s soldiers would need to be trained by Americans, and they’d be reliant on Americans for spare and replacement parts. Nasser really wanted to be armed by and tied to the Soviet Union, but had to pretend otherwise lest Eisenhower side with Britain, France, and Israel. So Nasser slowly sabotaged talks with the United States in such a way that made Washington seem unreasonable. That way, when he turned to the Soviet Union for weapons, he could half-plausibly say he had no choice.

Nasser did such a good job pretending to be pro-American that he convinced the United States to give him a world-class broadcasting network that allowed him to speak to the entire Arab world over the radio. Washington expected him to use his radio addresses to rally the Arab world behind America against the Russians. Instead, he used it to blast the United States with virulently anti-American propaganda and to undermine the West’s Arab allies. “Nasser,” Doran writes, “was the first revolutionary leader in the postwar Middle East to exploit the technology in order to call over the heads of the monarchs to the man on the street. Suddenly the Hashemite monarchy [in Iraq and Jordan] found itself sitting atop volcanoes.”

Nasser strode the Arab world like a colossus after his American-made victory in the Suez Crisis, and he became more brazenly anti-American as he gathered strength. Conning Ike was no longer possible, but Nasser didn’t need the United States anymore anyway.

Michael J. Totten, “We Are Still Living With Eisenhower’s Biggest Mistake”, The Tower Magazine, 2017-02.

July 19, 2018

Crony capitalists of the military-industrial complex

Matthew D. Mitchell comments on some of the problems with government contractors and their all-too-cosy relationship with the government officials who hand out the public’s funds:

… as economist Luigi Zingales explains in his book, A Capitalism for the People, governments contracting with private interests has its own set of risks:

The problem with many public-private partnerships is best captured by a comment that George Bernard Shaw once made to a beautiful ballerina. She had proposed that they have a child together so that the child could possess his brain and her beauty; Shaw replied that he feared the child would have her brain and his beauty. Similarly, public-private partnerships often wind up with the social goals of the private sector and the efficiency of the public one. In these partnerships, Republican and Democratic politicians and businesspeople frequently cooperate toward just one goal: their own profit.

When President Dwight Eisenhower warned against the “unwarranted influence” of the “military-industrial complex,” he was concerned that certain firms selling to the government might obtain untoward privilege, twisting public resources to serve private ends. It is telling that one of those contractors, Lockheed Aircraft, would become the first company to be bailed out by Congress in 1971.

For many observers, the George W. Bush administration’s “no-bid” contracts to Halliburton and Blackwater appeared to exemplify the sort of deals that Eisenhower had warned of. It is true that federal regulations explicitly permit contracts without open bidding in certain circumstances, such as when only one firm is capable of providing a certain service or when there is an unusual or compelling emergency. In any case, a report issued by the bipartisan Commission on Wartime Contracting in 2011 estimated that contractor fraud and abuse during operations in Afghanistan and Iraq cost taxpayers an estimated $31 to $60 billion. This includes, but is not limited to:

requirements that were excessive when established and/or not adjusted in a timely fashion; poor performance by contractors that required costly rework; ill-conceived projects that did not fit the cultural, political, and economic mores of the society they were meant to serve; security and other costs that were not anticipated due to lack of proper planning; questionable and unsupported payments to contractors that take years to reconcile; ineffective government oversight; and losses through lack of competition.

Governments may also award contracts to perform a service that has more to do with serving a parochial interest than with providing a benefit to the paying public. For example, Congress may order the Pentagon to procure more tanks even though the Pentagon itself says the tanks aren’t needed. Paying General Dynamics hundreds of millions of dollars to produce unneeded tanks in order to protect jobs in particular congressional districts may be an abuse even if the underlying process by which the contract was awarded is legitimate.

December 27, 2014

Who should have been the allied commanders on D-Day?

Nigel Davies ventures into alternatives again, this time looking at who were the best allied generals for the D-Day invasion (for the record, he’s quite right about the best Canadian corps commander):

The truth is that any successful high command should maximise the chances of success of any campaign by choosing the ‘best fit’ for the job.

But that is not how generals were chosen for D Day.

(I would love to start with divisional commanders, but there are way too many, so for space I will start with Corps and Army commanders, and work up to the top).

The outstanding Canadian of the campaign for instance was Guy Simonds. Described by many as the best Allied Corps commander in France, and credited with re-invigorating the Canadian Army HQ when he filled in while his less successful superior Harry Crerar was sick, Simonds was undoubtedly the standout Canadian officer in both Italy and France.Lieutenant General Guy Simonds, commander of the 2nd Canadian Corps.

He was however, the youngest Canadian division, corps or army commander, and the speed of his promotions pushed him past many superiors. He was also described as ‘cold and uninspiring’ even by those who called him ‘innovative and hard driving’. It can be taken as a two edged sword that Montgomery thought he was excellent (presumably implying Montgomery like qualities?) But his promotions seemed more related to ability than cronyism, and his achievements were undoubted.

Should he have been the Canadian Army commander instead of Crerar? Yes. Arguments against were mainly his lack of seniority, and lack of experience. but no Canadian had more experience, and lack of seniority was no bar in most of the other Allied armies.

It comes down to the simple fact that the Allied cause would have been better served by having Simonds in charge of Canadian forces than Crerar.

Simonds was a brilliant corps commander and (at least) a very good army commander, but he had one fatal flaw: he was no politician. Harry Crerar was a very “political” general, and played the political game with far greater talent than any other Canadian general. That got him into his role as army commander and his political skills kept him there despite the better “military” options available.

April 1, 2013

US Army forced by sequester cuts to eliminate several medals

The Duffel Blog is your source for all breaking US military news:

Lt. Gen. Howard B. Bromberg, the Army G-1, explained, “the amount of money spent on ribbons and medals has increased exponentially over the decades.” As proof, Bromberg pointed to a picture of Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, a five-star general, who was bedecked with only three ribbons.

“Today, we’d look at a private with only three ribbons as if he were some sort of dirtbag,” said Bromberg.

Although no final list had been decided upon, one Army spokesperson said that several ribbons were all but certain to be canned.

“The Army Service Ribbon? What the hell?,” asked the spokesman. “The fact that you’re in an Army uniform is proof of your army service. Why should I give you a damn ribbon?”

Army officials would neither confirm nor deny the fate of the National Defense Medal. One simply said, “So you were drinking beer in Germany, while the entire U.S. military was fighting Desert Storm? Remind us, again, why you deserve a medal?”

The Army indicated they would be cutting medals incrementally, starting with “I have a pulse”-tier awards, followed by “Thanks for showing up” awards, and finally, “I did an okay job” awards. Altogether, the program is expected to save $37 billion over the next decade.

December 28, 2012

The Military-Industrial Complex leads to “a bloated corporate state and a less dynamic private economy”

An older article from Christopher A. Preble, reposted at the Cato Institute website:

The true costs of the military-industrial complex, they explain, “have so far been understated, as they do not take into account the full forgone opportunities of the resources drawn into the war economy.” A dollar spent on planes and ships cannot also be spent on roads and bridges. What’s more, the existence of a permanent war economy, the specific condition which President Dwight Eisenhower warned of in his famous farewell address, has shifted some entrepreneurial behavior away from private enterprise, and toward the necessarily less efficient public sector. “The result,” Coyne and Duncan declaim, “is a bloated corporate state and a less dynamic private economy, the vibrancy of which is at the heart of increased standards of living.”

The process perpetuates itself. As more and more resources are diverted into the war economy, that may stifle — or at least impede — a healthy political debate over the proper size and scope of the entire national security infrastructure, another fact that Eisenhower anticipated. Simply put, people don’t like to bite the hand that feeds them.

And that hand feeds a lot of people. The Department of Defense is the single largest employer in the United States, with 1.4 million uniformed personnel on active duty, and more than 700,000 full-time civilians. The defense industry, meanwhile, is believed to employ another 3 million people, either directly or indirectly.

What’s more, these are high paying jobs. In 2010, when the average worker in the United States earned $44,400 in wages and benefits, the average within the aerospace and defense industry was $80,100, according to a study by the consulting firm Deloitte. And 80 percent of that industry’s revenue comes from the government.