Over the last several days, I’ve posted entries on what I think are the deep origins of the First World War (part one, part two, part three, part four). Up to now, we’ve been looking at the longer-term trends and policy shifts among the European great powers. Now, we’ll take a look at the most multicultural and diverse polity of the early 20th century, the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.

Austria becomes Austria-Hungary

Here is a map of Austria-Hungary at the start of the First World War:

A big central European empire: the second biggest empire in Europe at the time (after Russia). But that map manages to conceal nearly as much as it reveals. Here is a slightly more informative map, showing a similar map of ethnic and linguistic groups within the same geographical boundaries:

The ethnic groups of Austria-Hungary in 1910. Based on Distribution of Races in Austria-Hungary by William R. Shepherd, 1911. City names have been changed to those in use since 1945. (via Wikipedia)

This second map shows much more of the political reality of the empire — and these are merely the largest, most homogenous groupings — and why the Emperor was so sensitive to chauvinistic and nationalistic movements that appeared to threaten the stability of the realm. If anything, that map shows the southern regions of the empire — Croatia-Slavonia, Dalmatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina — to be more ethnically and linguistically compatible than almost any other region (which neatly illustrates some of the limitations of this form of analysis — layering on religious differences would make the map far more confusing, and yet in some ways more explanatory of what happened in 1914 … and, for that matter, from 1992 onwards).

Austria 1815-1866

For some reason, perhaps just common usage in history texts, I had the distinct notion that the Austrian Empire was a relatively continuous political and social structure from the Middle Ages onward. In reading a bit more on the nineteenth century, I find that the Austrian Empire was only “founded” in 1804 (according to Wikipedia, anyway). “Austria” as a concept certainly began far earlier than that! Austria was the general term for the personal holdings of the head of the Habsburgs. The title of Holy Roman Emperor had been synonymous with the Austrian head of state almost continuously since the fifteen century: that continuity was finally broken in 1806 when Emperor Francis II formally dissolved the Holy Roman Empire due to the terms of the Treaty of Pressburg, through which Napoleon stripped away many of the core holdings of the empire (including the Kingdom of Bavaria and the Kingdom of Württemberg) to create a new German proto-state called the Confederation of the Rhine.

The Confederation lasted until 1813, as Napoleon’s empire ebbed westward across the Rhine before the Prussian, Austrian, and Russian armies. After the Battle of Leipzig (also known as the Battle of Nations for the many different armies involved), several of the constituent parts of the Confederation defected to the allies. As part of the re-alignment of borders, treaties, and affiliations during the Congress of Vienna, both Prussia and Austria were added to the successor entity called the German Confederation, but Austria was the acknowledged leader of the organization.

The Rise of Prussia and the eclipse of Austria

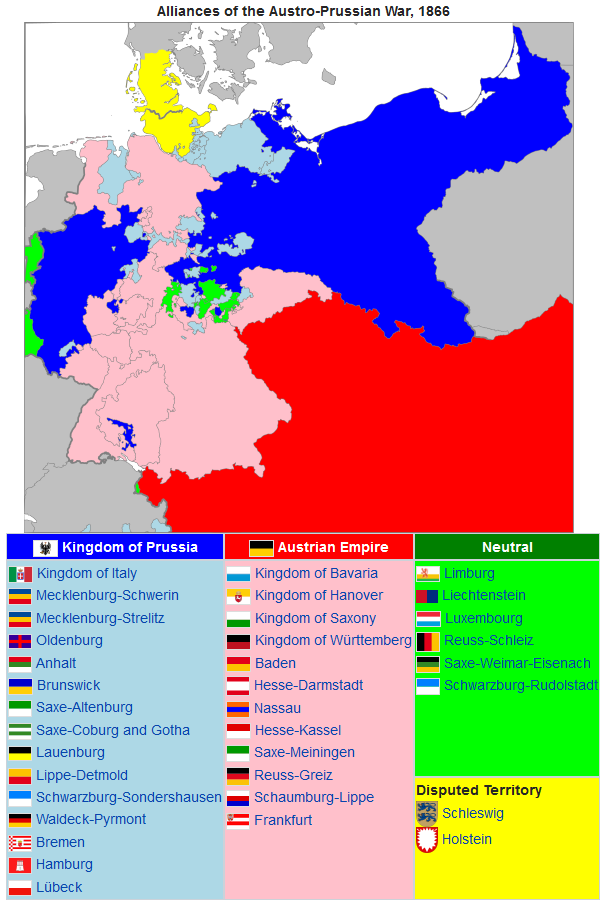

The Kingdom of Prussia was the rising power within the German Confederation, and it was likely that at some point the Prussians would attempt to challenge Austria for the leadership of Germany. That situation arose (or, if you’re a fan of the “Bismarck had a master plan” theory, was engineered) over the dispute with Denmark over the duchies of Holstein and Schleswig.Denmark was not part of the confederation, but the two duchies were within it: the right of succession to the the two ducal titles were a point of conflict between the Kingdom of Denmark (whose monarch was also in his own person the duke of both Schleswig and Holstein) and the leading powers of the confederation, Austria and Prussia. When the King of Denmark died, by some legal views, the right of succession to each of the ducal seats was now open to dispute (because they were not formally part of Denmark, despite the King having held those titles personally).

In Denmark proper, the recently adopted constitution provided for a greater degree of democratic representation, but the political system in the two duchies was much more tailored to the interests and representation of the landowning classes (who were predominantly German-speaking) over the commoners (who were Danish-speakers). After the new Danish King signed legislation setting up a common parliament for Denmark and Schleswig, Prussia invaded as part of a confederate army, and the Danes wisely retreated north, abandoning the relatively indefensible southern portion of the debated duchies. In short, the campaign went poorly for the Danes, but quite well for the Prussians and (to a lesser degree) the Austrians. Under the terms of the resulting Treaty of Vienna, Denmark renounced all claims to the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein, and Lauenburg to the Austrians and Prussians.

Austria’s reward for the campaign was the duchy of Holstein, while Prussia got Schleswig and Lauenburg (in the form of King Wilhelm taking on the rulership of the latter duchy in his own person). The two great powers soon found themselves at odds over the administration of the duchies, and Austria appealed their side of the dispute to the Diet (parliament) of the Confederation. Prussia declared this to be a violation of the Gastein Convention, and launched an invasion of Holstein in co-operation with some of the other Confederation states.

This was the start of the Austro-Prussian War, also known as the Seven Weeks’ War. The start of the conflict triggered an existing treaty between Prussia and Italy, bringing the Italian forces in to menace Austria’s southwestern frontier (Italy was eager to take the Italian-speaking regions of the Austrian Empire into their kingdom. As the Wikipedia entry notes, the war was not unwelcome to the respective leaders of the warring powers: “In Prussia king William I was deadlocked with the liberal parliament in Berlin. In Italy, king Victor Emmanuel II, faced increasing demands for reform from the Left. In Austria, Emperor Franz Joseph saw the need to reduce growing ethnic strife, by uniting the several nationalities against a foreign enemy.”

In his essay “Bismarck and Europe” (collected in From Napoleon to the Second International), A.J.P. Taylor notes that the war took time and effort to bring to fruition, but not for reasons you might expect:

The war between Austria and Prussia had been on the horizon for sixteen years. Yet it had great difficulty in getting itself declared. Austria tried to provoke Bismarck by placing the question of the duchies before the Diet on 1 June. Bismarck retaliated by occupying Holstein. He hoped that the Austrian troops there would resist, but they got away before he could catch them. On 14 June the Austrian motion for federal mobilization against Prussia was carried in the Diet. Prussia declared the confederation at an end; and on 15 June invaded Saxony. On 21 June, when Prussian troops reached the Austrian frontier, the crown prince, who was in command, merely notified the nearest Austrian officer that “a state of war” existed. That was all. The Italians did a little better La Marmora sent a declaration of war to Albrecht, the Austrian commander-in-chief, before taking the offensive. Both Italy and Prussia were committed to programmes which could not be justified in international law, and were bound to appear as aggressors if they put their claims on paper. The would, in fact, have been hard put to it to start the war if Austria had not done the job for them.

Strategically, the Austro-Prussian war was the first European war to reflect some of the lessons of the recently concluded American Civil War: railway transportation of significant forces to the front, and the relative firepower differences between muzzle-loading weapons (Austria) and breech-loading rifles (Prussia). In the decisive Battle of Königgrätz (or Sadová), Prussian firepower and strategic movement were the key factors, allowing the numerically smaller force to triumph — Austrian casualties were more than three times greater than those of the Prussian army. This was the last major battle of the war, with an armistice followed by the Peace of Prague ending hostilities.

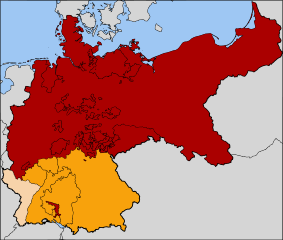

Initially, King Wilhelm had intended to utterly destroy Austrian power, possibly even to the extent of occupying significant portions of Austria, but Bismarck persuaded him that Prussia would be better served by offering a relatively lenient set of terms and working toward an alliance with the defeated Austrians than by the wholesale destruction of the balance of power. Austria lost the province of Venetia to Italy (although it was legally ceded to Napoleon III, who in turn ceded it to Italy). The German Confederation was replaced by a new North German Confederation led by Prussia’s King Wilhelm I as president, and Austria’s minor German allies were faced with a reparations bill to be paid to Prussia for their choice of allies in the war. (Liechtenstein at this time was separated from Austria and declared itself permanently neutral … I’d always wondered when that micro-state had popped into existence.)

Initially, King Wilhelm had intended to utterly destroy Austrian power, possibly even to the extent of occupying significant portions of Austria, but Bismarck persuaded him that Prussia would be better served by offering a relatively lenient set of terms and working toward an alliance with the defeated Austrians than by the wholesale destruction of the balance of power. Austria lost the province of Venetia to Italy (although it was legally ceded to Napoleon III, who in turn ceded it to Italy). The German Confederation was replaced by a new North German Confederation led by Prussia’s King Wilhelm I as president, and Austria’s minor German allies were faced with a reparations bill to be paid to Prussia for their choice of allies in the war. (Liechtenstein at this time was separated from Austria and declared itself permanently neutral … I’d always wondered when that micro-state had popped into existence.)

Aftermath and constitutional change

After a humiliating defeat by Prussia, the Austrian Emperor was faced with the need to rally the empire, and the Hungarian nationalists took this opportunity to again demand special rights and privileges within the empire. Hungary had always been, legally speaking, a separate kingdom within the empire that just happened to share a monarch with the rest of the empire. In 1867, this situation was recognized in the Compromise of 1867, after which the Austrian Empire was replaced by the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.

The necessity of satisfying Hungarian nationalist aspirations within the empire made Austria-Hungary appear as a political basket case to those more familiar with less ethnically, socially, and linguistically diverse polities than the Austrian Empire. From a more nationalistic viewpoint the political arrangements required to keep the empire together (mainly the issues in keeping Hungary happy) created a political system that appeared better suited to an asylum Christmas concert than a modern, functioning empire. In The Sleepwalkers, Christopher Clark explains the post-1867 government structure briefly:

Shaken by military defeat, the neo-absolutist Austrian Empire metamorphosed into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Under the Compromise hammered out in 1867 power was shared out between the two dominant nationalities, the Germans in the west and the Hungarians in the east. What emerged was a unique polity, like an egg with two yolks, in which the Kingdom of Hungary and a territory centred on the Austrian lands and often called Cisleithania (meaning ‘the lands on this side of the River Leithe’) lived side by side within the translucent envelope of a Habsburg dual monarchy. Each of the two entities had its own parliament, but there was no common prime minister and no common cabinet. Only foreign affairs, defence and defence-related aspects of finance were handled by ‘joint ministers’ who were answerable directly to the Emperor. Matters of interest to the empire as a whole could not be discussed in common parliamentary session, because to do so would have implied that the Kingdom of Hungary was merely the subordinate part of some larger imperial entity. Instead, an exchange of views had to take place between the ‘delegations’, groups of thirty delegates from each parliament, who met alternately in Vienna and Budapest.

Along with the bifurcation between Cisleithania and Transleithania (Hungary), the two governments handled the demands of their respective majority and minority subjects quite differently: the Hungarian government actively suppressed minorities and attempted to impost Magyarization programs through the schools to stamp out as much as they could of other linguistic and ethnic communities. The Hungarian plurality (about 48 percent of the population) controlled 90 percent of the seats in parliament, and the franchise was limited to those with landholdings. The lot of minorities in Cisleithania was much easier, as the government eventually extended the franchise to almost all adult men by 1907, although this did not completely address the linguistic demands of various minority groups.

Hungary also actively prevented any kind of political move to create a Slavic entity within the empire (in effect, turning the Dual Monarchy into a Triple Monarchy), for fear that Hungarian power would be diluted and also for fear of encouraging demands among the other minority groups in the Hungarian kingdom.

Rumours of the death of Austria: mainly in hindsight, not prognostication

After World War One, many memoirs and histories made reference to the inevitability of Austrian decline. Most of these “memories” appear to have been constructed after the fact, rather than being accurate views of the reality before the war began. Christopher Clark notes:

Evalutating the condition and prospects of the Austro-Hungarian Empire on the eve of the First World War confronts us in an acute way with the problem of temporal perspective. The collapse of the empire amid war and defeat in 1918 impressed itself upon the retrospective view of the Habsburg lands, overshadowing the scene with auguries of imminent and ineluctable decline. The Czech national activist Edvard Beneš was a case in point. During the First World War, Beneš became the organizer of a secret Czech pro-independence movement; in 1918, he was one of the founding fathers of the new Czechoslovak nation-state. But in a study of the “Austrian Problem and the Czech Question” published in 1908, he had expressed confidence in the future of the Habsburg commonwealth. “People have spoken of the dissolution of Austria. I do not believe in it at all. The historic and economic ties which bind the Austrian nations to one another are too strong to let such a thing happen.”

Austria’s economy

Far from being an economic basket case, Austrian economic growth topped 4.8% per year before the start of WW1 (Christopher Clark):

The Habsburg lands passed during the last pre-war decade through a phase of strong economic growth with a corresponding rise in general prosperity — an important point of contrast with the contemporary Ottoman Empire, but also with another classic collapsing polity, the Soviet Union of the 1980s. Free markets and competition across the empire’s vast customs union stimulated technical progress and the introduction of new products. The sheer size and diversity of the double monarchy meant that new industrial plants benefited from sophisticated networks of cooperating industries underpinned by an effective transport infrastructure and a high-quality service and support sector. The salutary economic effects were particularly evident in the Kingdom of Hungary.

Okay, enough about Austria for now … remember I said that the causes of the war were complex and inter-related? By this point I hope you’ll agree that this case has been more than proven … and we’re still not into the 20th century yet!