Published on Dec 1, 2016

H/T to Colby Cosh for the link.

Published on Dec 1, 2016

H/T to Colby Cosh for the link.

… most nations of Central and Eastern Europe were occupied by or allied with Germany during this period. The Nazis made it clear that deporting their Jews to the concentration camps in Nazi territory was a condition for continued good relations; a serious threat, when bad relations could turn a protectorate-type situation into an outright invasion and occupation.

Pride of place goes to Denmark and Bulgaria, both of which resisted all Nazi demands despite the Germans having almost complete power over them. Most people have heard the legend of how, when the Germans ordered that all Jews must wear gold stars, the King of Denmark said he would wear one too. These kinds of actions weren’t just symbolic; without cooperation from the Gentile population and common knowledge of who was or wasn’t Jewish, the Nazis had no good way to round people up for concentration camps. Nothing happened until 1943, when Himmler became so annoyed that he sent his personal agent Rolf Gunther to clean things up. Gunther tried hard but found the going impossible. Danish police refused to go door-to-door rounding up Jews, and when Gunther imported police from Germany, the Danes told them that they couldn’t break into apartments or else they would arrest them for breaking and entering. Then the Danish police tipped off Danish Jews not to open their doors to knocks since those might be German police. When it became clear that the Nazis weren’t going to accept any more delays, Danish fishermen offered to ferry Jews to neutral Sweden for free. In the end the Nazis only got a few hundred Danish Jews, and the Danish government made such a “fuss” (Arendt’s word) about them that the Nazis agreed to send them all to Theresienstadt, their less-murderous-than-usual camp, and let Red Cross observers in to make sure they were treated well. In the end, only 48 Danish Jews died in the entire Holocaust.

Bulgaria’s resistance was less immediately heroic, and looked less like the king proudly proclaiming his identity with oppressed people everywhere than with the whole government just dragging their feet so long that nothing got done. Eichmann sent an agent named Theodor Dannecker to get them moving, but as per Arendt:

not until about six months later did they take the first step in the direction of “radical” measures – the introduction of the Jewish badge. For the Nazis, even this turned out to be a great disappointment. In the first place, as they dutifully reported, the badge was only a “very little star”; second, most Jews simply did not wear it; and, third, those who did wear it received “so many manifestations of sympathy from the misled population that they actually are proud of their sign” – as Walter Schellenberg, Chief of Counterintelligence in the R.S.H.A., wrote in an S.D. report transmitted to the Foreign Office in November, 1942. Whereupon the Bulgarian government revoked the decree. Under great German pressure, the Bulgarian government finally decided to expel all Jews from Sofia to rural areas, but this measure was definitely not what the Germans demanded, since it dispersed the Jews instead of concentrating them.

The Bulgarians continued their policy of vaguely agreeing in principle to Nazi demands and then doing nothing, all the way until the Russians invaded and the time of danger was over. The result was that not a single Bulgarian Jew died in the Holocaust.

Scott Alexander, “Book review: Eichmann in Jerusalem”, Slate Star Codex, 2017-01-30.

Nicolai Sennels is a Danish psychologist who became the focus of debate on the influence of cultural and religious background and criminality:

After having consulted with 150 young Muslim clients in therapy and 100 Danish clients (who, on average, shared the same age and social background as their Muslim inmates), my findings were that the Muslims’ cultural and religious experiences played a central role in their psychological development and criminal behavior. “Criminal foreigners” is not just a generalizing and imprecise term. It is unfair to non-Muslim foreigners and generally misleading.

Discussing psychological characteristics of the Muslim culture is important. Denmark has foreigners from all over the world and according to official statistics from Danmarks Statistik all non-Muslim groups of immigrants are less criminal than the ethnic Danes. Even after adjusting, according to educational and economic levels, all Muslim groups are more criminal than any other ethnic group. Seven out of 10, in the youth prison where I worked, were Muslim.

[…]

Muslim culture has a very different view of anger and in many ways opposite to what we experience here in the West.

Expressions of anger and threats are probably the quickest way to lose one’s face in Western culture. In discussions, those who lose their temper have automatically lost, and I guess most people have observed the feeling of shame and loss of social status following expressions of aggression at one’s work place or at home. In the Muslim culture, aggressive behavior, especially threats, are generally seen to be accepted, and even expected as a way of handling conflicts and social discrepancies. If a Muslim does not respond in a threatening way to insults or social irritation, he, not “she” (Muslim women are, mostly, expected to be humble and to not show power) is seen as weak, as someone who cannot be depended upon and loses face.

In the eyes of most Westerners it looks immature and childish when people try to use threatening behavior, to mark their dislikes. A Danish saying goes “…Only small dogs bark. Big dogs do not have to.” That saying is deeply rooted in our cultural psychology as a guideline for civilized social behavior. To us, aggressive behavior is a clear sign of weakness. It is a sign of not being in control of oneself and lacking ability to handle a situation. We see peoples’ ability to remain calm as self confidence, allowing them to create a constructive dialogue. Their knowledge of facts, use of common sense and ability in producing valid arguments is seen as a sign of strength.

The Islamic expression of “holy anger” is therefore completely contradictory to any Western understanding. Those two words in the same sentence sound contradictory to us. The terror-threatening and violent reaction of Muslims to the Danish Mohammed cartoons showing their prophet as a man willing to use violence to spread his message, is seen from our Western eyes as ironic. Muslims’ aggressive reaction to a picture showing their prophet as aggressive, completely confirms the truth of the statement made by Kurt Westergaard in his satiric drawing.

This cultural difference is exceedingly important when dealing with Muslim regimes and organizations. Our way of handling political disagreement goes through diplomatic dialogue, and calls on Muslim leaders to use compassion, compromise and common sense. This peaceful approach is seen by Muslims as an expression of weakness and lack of courage. Thus avoiding the risks of a real fight is seen by them as weakness; when experienced in Muslim culture, it is an invitation to exploitation.

On the National Interest Blog, James Hasik points out that the idea of the Littoral Combat Ships of the US Navy was successfully implemented more than twenty years ago (and much more economically, too):

In contrast, we know it’s possible to get modularity right, because the Royal Danish Navy has been getting it right since the early 1990s. Way back in 1985, Danyard laid down the Flyvefisken (Flying Fish), the first of a class of 14 patrol vessels. The ships were intended to fight the Warsaw Pact on the Baltic — a sea littoral throughout, with an average depth of 180 feet, and a width nowhere greater than 120 miles. Any navy on its waters might find itself fighting surface ships, diesel submarines, rapidly ingressing aircraft, and sea mines in close order. On the budget of a country of fewer than six million people, the Danes figured that they should maximize the utility of any given ship. That meant standardizing a system of modules for flexible mission assignment. The result was the Stanflex modular payload system.

At 450 tons full load, a Flyvefisken is much smaller than a Freedom (3900 tons) or an Independence (3100 tons). Her complement is much smaller too: 19 to 29, depending on the role. At not more than 15 tons, the Stanflex modules are also smaller than the particular system designed anew for the LCSs. But a Flyvefisken came with four such slots (one forward, three aft), and a range of modules surprisingly broad […]

Swapping modules pier-side requires a few hours and a 15-ton crane. Truing the gun module takes some hours longer. Retraining the crew is another matter, but modular specialists can be swapped too. The concept has had some staying power. The Flyvefiskens served Denmark as recently as 2010. In a commercial vote of confidence, the Lithuanian Navy bought three secondhand, and the Portuguese Navy four (as well as a fifth for spare parts). Over time, the Royal Danish Navy has provided Stanflex slots and modules to all its subsequent ships: the former Niels Juel-class corvettes, the Thetis-class frigates, the Knud Rasmussen-class patrol ships, the well-regarded Absalon-class command-and-support ships, and the new Ivar Huitfeldt-class frigates.

Flyvefisken-class patrol ship HDMS Skaden (hull number P561) and HDMS Thetis (F357) in Copenhagen (via WikiMedia)

In short, 25 years ago the Danes figured out how a single ship could hunt and kill mines, submarines and surface ships. A small ship can’t do all those things well at once, but that’s a choice in fleet architecture. Whatever we think of the LCS program, we shouldn’t draw the wrong lessons from it. Why is this important? Modularity is economical, as the Danes have long known. Critically, modularity also lends flexibility in recovering from wartime surprise, in that platforms can be readily provided new payloads without starting from scratch. Because on December the 8th, when you need a face-punched plan, you’d rather be building new boxes than new whole new ships.

Wikipedia has this image of the HDMS Iver Huitfeldt:

A brief post at Real Clear Science on a recent discovery in human immunology:

Think again if you thought that doctors had long since identified and described exactly how the body defends itself against microorganisms.

Scientists have recently discovered a whole new side to the immune system: a rapid immune response that kicks in well before any of the other known mechanisms.

“I hate to use the term ‘text books will write about this’, but this [discovery] really is brand new and we will need to write a new chapter,” says co-author Søren R. Paludan, professor of virology and immunology form the Department of Biomedicine, Aarhus University, Denmark.

In collaboration with groups from the US and Germany, the scientists showed that when the body’s outer defence, the mucosa lining that surrounds certain organs, is disturbed by a virus, the underlying layer of cells are the first to react and sound the alarm. They summon the body’s cell soldiers, which attack the invading virus.

Both this alarm system and the ‘soldier’ cells operate completely separately from what were believed to be the first responders to immune system attacks.

Terry Teachout wrote about Danish comedian/pianist Victor Borge back in 2005:

I doubt that many people under the age of forty remember Victor Borge, the comedian-pianist who died in 2000 at the miraculous age of ninety-one. He was a star for a very long time, first on radio, then TV, and Comedy in Music, his 1953 one-man show, ran for 849 consecutive performances on Broadway, a record which so far as I know remains unbroken. From there he went on the road and stayed there, giving sixty-odd concerts in the season before his death. Borge spent his old age basically doing Comedy in Music over and over again, which never seemed to bother anybody. I reviewed it twice for the Kansas City Star in the Seventies, and loved it both times. His Danish-accented delivery was so droll and his timing so devastatingly exact that even the most familiar of his charming classical-music spoofs somehow remained fresh, as you can see by watching any of the various videos of his act.

It’s hard to imagine that there was a time when so popular a comedian started out as a serious musician, much less one who became popular by making witty fun of the classics. Such a thing could only have happened in the days when America’s middlebrow culture was still intact and at the height of its influence. Back then the mass media, especially TV, went out of their way to introduce ordinary people to classical music and encouraged them to take it seriously–which didn’t mean they couldn’t laugh at it, too, as Borge proved whenever he sat down to play.

Borge’s act resembled a straight piano recital gone wrong. He’d start to play a familiar piece like Clair de lune or the “Moonlight” Sonata, then swerve off in some improbable-sounding direction, never getting around to finishing what he started. Yet he was clearly an accomplished pianist, though few of his latter-day fans had any idea how good he’d been (he studied with Egon Petri, Busoni’s greatest pupil). He usually made a point of playing a piece from start to finish toward the end of every concert, and I remember how delighted I was each time I heard him ripple through one of Ignaz Friedman’s bittersweet Viennese-waltz arrangements, which he played with a deceptively nonchalant old-world panache that never failed to leave me longing for an encore. Alas, he never obliged, and in later years I found myself wondering whether he’d really been quite so fine as my memory told me.

At Strategy Page, Austin Bay talks about the unusual attention paid to a Danish island in the Baltic Sea by Russian military forces:

Denmark’s Bornholm Island apparently troubles Vladimir Putin’s 21st-century Kremlin war planners as much as it vexed their Cold War Soviet-era predecessors.

More on Bornholm’s specifics in a moment, but first let’s cover one more example of Putin Russia’s aggressive wrong doing. According to an open-source Danish security assessment, in mid-June 2014, three months after Putin’s Kremlin attacked and annexed Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula, Russian aircraft carrying live missiles bluffed an attack on Bornholm. Though the report doesn’t provide the exact date, the bomber “probe” occurred during the three-day period the island hosted a touchy-feely “peoples festival.” The festival’s 90,000 participants were unaware they were seeking peaceful solutions on a bulls-eye.

The Bornholm faux-attack reprised Soviet Cold War “tests” of Danish defenses and is but one of a score of serious Russian military probes since 2008 designed to rattle Northern Europe. These Kremlin air and naval probes, backed by harsh rhetoric, have led Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland to reassess their military defenses. “Nordic cooperation” with an emphasis on territorial defense was the first formulation. The Nordics, however, acknowledged ties to Baltic states (and NATO members) Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Since the Crimea invasion, Denmark and Norway (NATO members) want to reinvigorate NATO military capabilities. Continued Russian aggression in Ukraine has led a few habitually neutral Swedes to voice an interest in joining NATO.

Bornholm Island (via Google Maps)

Back to Bornholm: the island’s location and geology irritated Soviet-era Kremlin strategists. Located in the Baltic Sea east of peninsular Denmark, north of Poland’s coast and to the rear of what was East Germany, Bornholm gave the Free World outpost north of and behind Warsaw Pact lines.

Soviet communications security officers despised the place. Bornholm’s electronic intercept systems, quite literally, bugged them.

As for geology, unlike Jutland’s flat peninsula, Bornholm is rock. In the 1970s, while serving a U.S. Army tour in West Germany, I heard a senior officer describe Bornholm as “sort of a Gibraltar.” His exaggeration had a point. Dig tunnels and Bornholm became a hard target for Soviet conventional weapons.

Published on 16 Mar 2015

Indy sits in the chair of wisdom to answer your questions about World War 1. This week you asked about the chance of Scandinavia joining the war and what was the deal with Canada?

In the New York Post, Kyle Smith has a go at de-smugging one of the smuggest countries in the world … no, it’s not Canada (but we’re pretty damned smug ourselves):

Want proof that the liberal social-democratic society works?

Look to Denmark, the country that routinely leads the world in happiness surveys. It’s also notable for having the highest taxes on Earth, plus a comfy social-safety net: Child care is mostly free, as is public school and even private school, and you can stay on unemployment benefits for a long time. Everyone is on an equal footing, both income-wise and socially: Go to a party and you wouldn’t be surprised to see a TV star talking to a roofer.

The combination of massive taxes and benefits for the unsuccessful means top and bottom get shaved off: Pretty much everyone is proudly middle class. Danes belong to more civic associations and clubs than anyone else; they love performing in large groups. At Christmas they do wacky things like hold hands and run around the house together, singing festive songs. They’re a real-life Whoville.

In the American liberal compass, the needle is always pointing to places like Denmark. Everything they most fervently hope for here has already happened there.

So: Why does no one seem particularly interested in visiting Denmark? (“Honey, on our European trip, I want to see Tuscany, Paris, Berlin and … Jutland!”) Visitors say Danes are joyless to be around. Denmark suffers from high rates of alcoholism. In its use of antidepressants it ranks fourth in the world. (Its fellow Nordics the Icelanders are in front by a wide margin.) Some 5% of Danish men have had sex with an animal. Denmark’s productivity is in decline, its workers put in only 28 hours a week, and everybody you meet seems to have a government job. Oh, and as The Telegraph put it, it’s “the cancer capital of the world.”

So how happy can these drunk, depressed, lazy, tumor-ridden, pig-bonking bureaucrats really be?

In his daily-or-so Forbes post, Tim Worstall explains the real reason why it will be somewhere between difficult and impossible to turn the United States into a Scandinavian mixed economy like Denmark:

The essence of the argument is that sure, we’d like quite a lot of equity in how the economy works out. Wouldn’t mind that large (but efficient! of which more later) welfare state. We’d also like to have continuing economic growth of course, so that our children are better off than we are, theirs than they and so on. And we can have that welfare state and equity just by taxing the snot out of everyone but that does rather impact upon that growth. So, the solution is to have as classically liberal an economy as one can, with the least regulation of who does what and how, then tax the snot out of it to pay for that welfare state. Not that Sumner put it in quite those words of course.

The lesson so far being that if the American left want to turn the US into Scandinavia, well, OK, but they’re going to have to pull back on most of the economic regulation they’ve encumbered the country with over the past 50 years.

The other point is an observation of my own. Which is that those Scandinavian welfare states are very local. To give you my oft used example, the national income tax rate in Denmark starts out at 3.76% and peaks at 15%. There’s also very stiff, 25-30% of income, taxes at the commune level. A commune being possibly as small as a township in the US, 10,000 people. The point being that this welfare state is paid for out of taxes raised locally and spent locally. Entirely the opposite way around from the way that the American left tells us that the US should work: all that money goes off to Washington and then the bright technocrats disburse it.

Instead they have what I call the Bjorn’s Beer Effect. You’re in a society of 10,000 people. You know the guy who raises the local tax money and allocates that local tax money. You also know where he has a beer on a Friday night. More importantly Bjorn knows that everyone knows he collects and spends the money: and also where he has a beer on a Friday. That money is going to be rather better spent than if it travels off possibly 3,000 miles into some faceless bureaucracy. I give you as an example Danish social housing or the vertical slums that HUD has built in the past. And if people think their money is being well spent then they’re likely to support more of it being spent.

[…]

So, the two things I would say need to be done as precursors to turning the united States into Scandinavia are the following. First we need to move back to a much less regulated, more classically liberal, economy. Secondly we need to push the whole tax system and welfare state provision down from the Federal government down to much smaller units. Possibly even right down to the counties. The first of these will generate the economic growth to pay for that expanded welfare state, the second make people more willing to pay for it.

If you find any American leftists out there willing to agree to these two preconditions do let me know. Because I’ve never met a single one who would think that those were things worth doing in order to get that social democracy they say they desire.

Over the last several days, I’ve posted entries on what I think are the deep origins of the First World War (part one, part two, part three, part four). Up to now, we’ve been looking at the longer-term trends and policy shifts among the European great powers. Now, we’ll take a look at the most multicultural and diverse polity of the early 20th century, the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.

Austria becomes Austria-Hungary

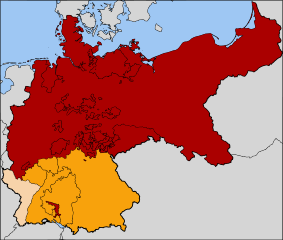

Here is a map of Austria-Hungary at the start of the First World War:

A big central European empire: the second biggest empire in Europe at the time (after Russia). But that map manages to conceal nearly as much as it reveals. Here is a slightly more informative map, showing a similar map of ethnic and linguistic groups within the same geographical boundaries:

The ethnic groups of Austria-Hungary in 1910. Based on Distribution of Races in Austria-Hungary by William R. Shepherd, 1911. City names have been changed to those in use since 1945. (via Wikipedia)

This second map shows much more of the political reality of the empire — and these are merely the largest, most homogenous groupings — and why the Emperor was so sensitive to chauvinistic and nationalistic movements that appeared to threaten the stability of the realm. If anything, that map shows the southern regions of the empire — Croatia-Slavonia, Dalmatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina — to be more ethnically and linguistically compatible than almost any other region (which neatly illustrates some of the limitations of this form of analysis — layering on religious differences would make the map far more confusing, and yet in some ways more explanatory of what happened in 1914 … and, for that matter, from 1992 onwards).

Austria 1815-1866

For some reason, perhaps just common usage in history texts, I had the distinct notion that the Austrian Empire was a relatively continuous political and social structure from the Middle Ages onward. In reading a bit more on the nineteenth century, I find that the Austrian Empire was only “founded” in 1804 (according to Wikipedia, anyway). “Austria” as a concept certainly began far earlier than that! Austria was the general term for the personal holdings of the head of the Habsburgs. The title of Holy Roman Emperor had been synonymous with the Austrian head of state almost continuously since the fifteen century: that continuity was finally broken in 1806 when Emperor Francis II formally dissolved the Holy Roman Empire due to the terms of the Treaty of Pressburg, through which Napoleon stripped away many of the core holdings of the empire (including the Kingdom of Bavaria and the Kingdom of Württemberg) to create a new German proto-state called the Confederation of the Rhine.

The Confederation lasted until 1813, as Napoleon’s empire ebbed westward across the Rhine before the Prussian, Austrian, and Russian armies. After the Battle of Leipzig (also known as the Battle of Nations for the many different armies involved), several of the constituent parts of the Confederation defected to the allies. As part of the re-alignment of borders, treaties, and affiliations during the Congress of Vienna, both Prussia and Austria were added to the successor entity called the German Confederation, but Austria was the acknowledged leader of the organization.

The Rise of Prussia and the eclipse of Austria

The Kingdom of Prussia was the rising power within the German Confederation, and it was likely that at some point the Prussians would attempt to challenge Austria for the leadership of Germany. That situation arose (or, if you’re a fan of the “Bismarck had a master plan” theory, was engineered) over the dispute with Denmark over the duchies of Holstein and Schleswig.Denmark was not part of the confederation, but the two duchies were within it: the right of succession to the the two ducal titles were a point of conflict between the Kingdom of Denmark (whose monarch was also in his own person the duke of both Schleswig and Holstein) and the leading powers of the confederation, Austria and Prussia. When the King of Denmark died, by some legal views, the right of succession to each of the ducal seats was now open to dispute (because they were not formally part of Denmark, despite the King having held those titles personally).

In Denmark proper, the recently adopted constitution provided for a greater degree of democratic representation, but the political system in the two duchies was much more tailored to the interests and representation of the landowning classes (who were predominantly German-speaking) over the commoners (who were Danish-speakers). After the new Danish King signed legislation setting up a common parliament for Denmark and Schleswig, Prussia invaded as part of a confederate army, and the Danes wisely retreated north, abandoning the relatively indefensible southern portion of the debated duchies. In short, the campaign went poorly for the Danes, but quite well for the Prussians and (to a lesser degree) the Austrians. Under the terms of the resulting Treaty of Vienna, Denmark renounced all claims to the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein, and Lauenburg to the Austrians and Prussians.

Austria’s reward for the campaign was the duchy of Holstein, while Prussia got Schleswig and Lauenburg (in the form of King Wilhelm taking on the rulership of the latter duchy in his own person). The two great powers soon found themselves at odds over the administration of the duchies, and Austria appealed their side of the dispute to the Diet (parliament) of the Confederation. Prussia declared this to be a violation of the Gastein Convention, and launched an invasion of Holstein in co-operation with some of the other Confederation states.

This was the start of the Austro-Prussian War, also known as the Seven Weeks’ War. The start of the conflict triggered an existing treaty between Prussia and Italy, bringing the Italian forces in to menace Austria’s southwestern frontier (Italy was eager to take the Italian-speaking regions of the Austrian Empire into their kingdom. As the Wikipedia entry notes, the war was not unwelcome to the respective leaders of the warring powers: “In Prussia king William I was deadlocked with the liberal parliament in Berlin. In Italy, king Victor Emmanuel II, faced increasing demands for reform from the Left. In Austria, Emperor Franz Joseph saw the need to reduce growing ethnic strife, by uniting the several nationalities against a foreign enemy.”

In his essay “Bismarck and Europe” (collected in From Napoleon to the Second International), A.J.P. Taylor notes that the war took time and effort to bring to fruition, but not for reasons you might expect:

The war between Austria and Prussia had been on the horizon for sixteen years. Yet it had great difficulty in getting itself declared. Austria tried to provoke Bismarck by placing the question of the duchies before the Diet on 1 June. Bismarck retaliated by occupying Holstein. He hoped that the Austrian troops there would resist, but they got away before he could catch them. On 14 June the Austrian motion for federal mobilization against Prussia was carried in the Diet. Prussia declared the confederation at an end; and on 15 June invaded Saxony. On 21 June, when Prussian troops reached the Austrian frontier, the crown prince, who was in command, merely notified the nearest Austrian officer that “a state of war” existed. That was all. The Italians did a little better La Marmora sent a declaration of war to Albrecht, the Austrian commander-in-chief, before taking the offensive. Both Italy and Prussia were committed to programmes which could not be justified in international law, and were bound to appear as aggressors if they put their claims on paper. The would, in fact, have been hard put to it to start the war if Austria had not done the job for them.

Strategically, the Austro-Prussian war was the first European war to reflect some of the lessons of the recently concluded American Civil War: railway transportation of significant forces to the front, and the relative firepower differences between muzzle-loading weapons (Austria) and breech-loading rifles (Prussia). In the decisive Battle of Königgrätz (or Sadová), Prussian firepower and strategic movement were the key factors, allowing the numerically smaller force to triumph — Austrian casualties were more than three times greater than those of the Prussian army. This was the last major battle of the war, with an armistice followed by the Peace of Prague ending hostilities.

Initially, King Wilhelm had intended to utterly destroy Austrian power, possibly even to the extent of occupying significant portions of Austria, but Bismarck persuaded him that Prussia would be better served by offering a relatively lenient set of terms and working toward an alliance with the defeated Austrians than by the wholesale destruction of the balance of power. Austria lost the province of Venetia to Italy (although it was legally ceded to Napoleon III, who in turn ceded it to Italy). The German Confederation was replaced by a new North German Confederation led by Prussia’s King Wilhelm I as president, and Austria’s minor German allies were faced with a reparations bill to be paid to Prussia for their choice of allies in the war. (Liechtenstein at this time was separated from Austria and declared itself permanently neutral … I’d always wondered when that micro-state had popped into existence.)

Initially, King Wilhelm had intended to utterly destroy Austrian power, possibly even to the extent of occupying significant portions of Austria, but Bismarck persuaded him that Prussia would be better served by offering a relatively lenient set of terms and working toward an alliance with the defeated Austrians than by the wholesale destruction of the balance of power. Austria lost the province of Venetia to Italy (although it was legally ceded to Napoleon III, who in turn ceded it to Italy). The German Confederation was replaced by a new North German Confederation led by Prussia’s King Wilhelm I as president, and Austria’s minor German allies were faced with a reparations bill to be paid to Prussia for their choice of allies in the war. (Liechtenstein at this time was separated from Austria and declared itself permanently neutral … I’d always wondered when that micro-state had popped into existence.)

Aftermath and constitutional change

After a humiliating defeat by Prussia, the Austrian Emperor was faced with the need to rally the empire, and the Hungarian nationalists took this opportunity to again demand special rights and privileges within the empire. Hungary had always been, legally speaking, a separate kingdom within the empire that just happened to share a monarch with the rest of the empire. In 1867, this situation was recognized in the Compromise of 1867, after which the Austrian Empire was replaced by the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.

The necessity of satisfying Hungarian nationalist aspirations within the empire made Austria-Hungary appear as a political basket case to those more familiar with less ethnically, socially, and linguistically diverse polities than the Austrian Empire. From a more nationalistic viewpoint the political arrangements required to keep the empire together (mainly the issues in keeping Hungary happy) created a political system that appeared better suited to an asylum Christmas concert than a modern, functioning empire. In The Sleepwalkers, Christopher Clark explains the post-1867 government structure briefly:

Shaken by military defeat, the neo-absolutist Austrian Empire metamorphosed into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Under the Compromise hammered out in 1867 power was shared out between the two dominant nationalities, the Germans in the west and the Hungarians in the east. What emerged was a unique polity, like an egg with two yolks, in which the Kingdom of Hungary and a territory centred on the Austrian lands and often called Cisleithania (meaning ‘the lands on this side of the River Leithe’) lived side by side within the translucent envelope of a Habsburg dual monarchy. Each of the two entities had its own parliament, but there was no common prime minister and no common cabinet. Only foreign affairs, defence and defence-related aspects of finance were handled by ‘joint ministers’ who were answerable directly to the Emperor. Matters of interest to the empire as a whole could not be discussed in common parliamentary session, because to do so would have implied that the Kingdom of Hungary was merely the subordinate part of some larger imperial entity. Instead, an exchange of views had to take place between the ‘delegations’, groups of thirty delegates from each parliament, who met alternately in Vienna and Budapest.

Along with the bifurcation between Cisleithania and Transleithania (Hungary), the two governments handled the demands of their respective majority and minority subjects quite differently: the Hungarian government actively suppressed minorities and attempted to impost Magyarization programs through the schools to stamp out as much as they could of other linguistic and ethnic communities. The Hungarian plurality (about 48 percent of the population) controlled 90 percent of the seats in parliament, and the franchise was limited to those with landholdings. The lot of minorities in Cisleithania was much easier, as the government eventually extended the franchise to almost all adult men by 1907, although this did not completely address the linguistic demands of various minority groups.

Hungary also actively prevented any kind of political move to create a Slavic entity within the empire (in effect, turning the Dual Monarchy into a Triple Monarchy), for fear that Hungarian power would be diluted and also for fear of encouraging demands among the other minority groups in the Hungarian kingdom.

Rumours of the death of Austria: mainly in hindsight, not prognostication

After World War One, many memoirs and histories made reference to the inevitability of Austrian decline. Most of these “memories” appear to have been constructed after the fact, rather than being accurate views of the reality before the war began. Christopher Clark notes:

Evalutating the condition and prospects of the Austro-Hungarian Empire on the eve of the First World War confronts us in an acute way with the problem of temporal perspective. The collapse of the empire amid war and defeat in 1918 impressed itself upon the retrospective view of the Habsburg lands, overshadowing the scene with auguries of imminent and ineluctable decline. The Czech national activist Edvard Beneš was a case in point. During the First World War, Beneš became the organizer of a secret Czech pro-independence movement; in 1918, he was one of the founding fathers of the new Czechoslovak nation-state. But in a study of the “Austrian Problem and the Czech Question” published in 1908, he had expressed confidence in the future of the Habsburg commonwealth. “People have spoken of the dissolution of Austria. I do not believe in it at all. The historic and economic ties which bind the Austrian nations to one another are too strong to let such a thing happen.”

Austria’s economy

Far from being an economic basket case, Austrian economic growth topped 4.8% per year before the start of WW1 (Christopher Clark):

The Habsburg lands passed during the last pre-war decade through a phase of strong economic growth with a corresponding rise in general prosperity — an important point of contrast with the contemporary Ottoman Empire, but also with another classic collapsing polity, the Soviet Union of the 1980s. Free markets and competition across the empire’s vast customs union stimulated technical progress and the introduction of new products. The sheer size and diversity of the double monarchy meant that new industrial plants benefited from sophisticated networks of cooperating industries underpinned by an effective transport infrastructure and a high-quality service and support sector. The salutary economic effects were particularly evident in the Kingdom of Hungary.

Okay, enough about Austria for now … remember I said that the causes of the war were complex and inter-related? By this point I hope you’ll agree that this case has been more than proven … and we’re still not into the 20th century yet!

James Delingpole isn’t kidding:

If I’d been anywhere near Denmark that day, I too would have eagerly dragged my kids along to the zoo’s operating theatre to witness the ghoulish but fascinating Inside Nature’s Giants-style spectacle.

Why? Well, partly for my entertainment and education, but mainly for the sake of my children. I know we all love to idealise our offspring as sensitive, bunny-hugging little moppets who wouldn’t hurt a flea. But the truth is that there are few things kids enjoy more than a nice, juicy carcase with its guts hanging out. Dead birds are good; dead badgers are better; a dead giraffe is all but unbeatable.

You first tend to notice this trait on family walks. Desperately, you’ll try to keep your reluctant toddler going by showing it lots of fascinating things. Sheep or tractors may do the job, just about. But not nearly as well, say, as a dead rabbit with its belly distended with putrefaction and flies crawling over its empty eye sockets. It’s your child’s introduction to a concept we all have to grapple with in the end: what Damien Hirst once called “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living”.

This, no doubt, is one of the reasons for the enduring popularity of Roald Dahl. Dahl’s brilliant insight is that children, au fond, are horrid little sickos who like nothing better than stories about giants who steal you from your bed in the night to murder you, and enormous crocodiles that gobble you all up. His is a natural world red in tooth and claw: Fantastic Mr Fox really does slaughter chickens — because he’s a fox — and when he gets his tail shot off you know, much as you might wish it otherwise, that it is never ever going to grow back.

[…]

Which reminds me: one of the stupidest mistakes made by Copenhagen Zoo was to have given that two-year-old giraffe such an affecting name. “Catomeat” might have worked. But to call a giraffe you’re planning to chop up and then chuck into the lions’ den “Marius” is surely asking for trouble. I wouldn’t want to execute a giraffe called “Marius”, would you?

I do, though, think that as a culture we need to be more grown-up about this sort of thing. If we’re going to have zoos and safari parks (as I believe we should; most of us will never have the money to enable our kids to see these wonders in the wild), then we have to accept the consequences. One of these is that sick, inbred, overpopulous or dangerous stock (like the six lions recently put down at Longleat) will have, on occasion, to be culled. Yes, it’s not ideal, but that unfortunately is how the world works. With animals, as with humans, the deal is this: none of us gets out of here alive.

Canadians are often found wanting in comparison to Norwegians, Swedes, Finns, or Danes in any international ranking. Except for smugness, where Canada (of course) is the undisputed world leader. But according to Michael Booth, things are not quite as wonderful in Scandinavia as we’re led to believe:

Whether it is Denmark’s happiness, its restaurants, or TV dramas; Sweden’s gender equality, crime novels and retail giants; Finland’s schools; Norway’s oil wealth and weird songs about foxes; or Iceland’s bounce-back from the financial abyss, we have an insatiable appetite for positive Nordic news stories. After decades dreaming of life among olive trees and vineyards, these days for some reason, we Brits are now projecting our need for the existence of an earthly paradise northwards.

I have contributed to the relentless Tetris shower of print columns on the wonders of Scandinavia myself over the years but now I say: enough! Nu er det nok! Enough with foraging for dinner. Enough with the impractical minimalist interiors. Enough with the envious reports on the abolition of gender-specific pronouns. Enough of the unblinking idolatry of all things knitted, bearded, rye bread-based and licorice-laced. It is time to redress the imbalance, shed a little light Beyond the Wall.

First, let’s look at Denmark, where Booth has lived for several years:

Why do the Danes score so highly on international happiness surveys? Well, they do have high levels of trust and social cohesion, and do very nicely from industrial pork products, but according to the OECD they also work fewer hours per year than most of the rest of the world. As a result, productivity is worryingly sluggish. How can they afford all those expensively foraged meals and hand-knitted woollens? Simple, the Danes also have the highest level of private debt in the world (four times as much as the Italians, to put it into context; enough to warrant a warning from the IMF), while more than half of them admit to using the black market to obtain goods and services.

Perhaps the Danes’ dirtiest secret is that, according to a 2012 report from the Worldwide Fund for Nature, they have the fourth largest per capita ecological footprint in the world. Even ahead of the US. Those offshore windmills may look impressive as you land at Kastrup, but Denmark burns an awful lot of coal. Worth bearing that in mind the next time a Dane wags her finger at your patio heater.

Okay, but how about Norway? Aren’t they doing well?

The dignity and resolve of the Norwegian people in the wake of the attacks by Anders Behring Breivik in July 2011 was deeply impressive, but in September the rightwing, anti-Islamist Progress party — of which Breivik had been an active member for many years — won 16.3% of the vote in the general election, enough to elevate it into coalition government for the first time in its history. There remains a disturbing Islamophobic sub-subculture in Norway. Ask the Danes, and they will tell you that the Norwegians are the most insular and xenophobic of all the Scandinavians, and it is true that since they came into a bit of money in the 1970s the Norwegians have become increasingly Scrooge-like, hoarding their gold, fearful of outsiders.

Finland? I’ve always gotten on famously with Finns (and Estonians), although I haven’t met all that many of them:

I am very fond of the Finns, a most pragmatic, redoubtable people with a Sahara-dry sense of humour. But would I want to live in Finland? In summer, you’ll be plagued by mosquitos, in winter, you’ll freeze — that’s assuming no one shoots you, or you don’t shoot yourself. Finland ranks third in global gun ownership behind only America and Yemen; has the highest murder rate in western Europe, double that of the UK; and by far the highest suicide rate in the Nordic countries.

The Finns are epic Friday-night bingers and alcohol is now the leading cause of death for Finnish men. “At some point in the evening around 11.30pm, people start behaving aggressively, throwing punches, wrestling,” Heikki Aittokoski, foreign editor of Helsingin Sanomat, told me. “The next day, people laugh about it. In the US, they’d have an intervention.”

[…]

If you do decide to move there, don’t expect scintillating conversation. Finland’s is a reactive, listening culture, burdened by taboos too many to mention (civil war, second world war and cold war-related, mostly). They’re not big on chat. Look up the word “reticent” in the dictionary and you won’t find a picture of an awkward Finn standing in a corner looking at his shoelaces, but you should.

“We would always prefer to be alone,” a Finnish woman once admitted to me. She worked for the tourist board.

Sweden, though, must be the one without any real serious issues, right?

Anything I say about the Swedes will pale in comparison to their own excoriating self-image. A few years ago, the Swedish Institute of Public Opinion Research asked young Swedes to describe their compatriots. The top eight adjectives they chose were: envious, stiff, industrious, nature loving, quiet, honest, dishonest, xenophobic.

I met with Åke Daun, Sweden’s most venerable ethnologist. “Swedes seem not to ‘feel as strongly’ as certain other people”, Daun writes in his excellent book, Swedish Mentality. “Swedish women try to moan as little as possible during childbirth and they often ask, when it is all over, whether they screamed very much. They are very pleased to be told they did not.” Apparently, crying at funerals is frowned upon and “remembered long afterwards”. The Swedes are, he says, “highly adept at insulating themselves from each other”. They will do anything to avoid sharing a lift with a stranger, as I found out during a day-long experiment behaving as un-Swedishly as possible in Stockholm.

H/T to Kathy Shaidle (via Facebook) for the link.

Developments like this should be of great interest to the Royal Canadian Navy:

… constrained budgets in America and Europe are prompting leading nations to reconsider future needs and explore whether new ships should be tailored for what they do every day, rather than what they might have to do once over decades.

The solution: extreme flexibility at an affordable price for construction and operation.

Here the Danes have emerged as a clear leader by developing two classes of highly innovative ships designed to operate as how they will be used: carrying out coalition operations while equipped to swing from high-end to low-end missions.

The three Iver Huitfeldt frigates and two Absalon flexible support ships share a common, large, highly efficient hull to yield long-range, efficient but highly flexible ships that come equipped with considerable capabilities — from large cargo and troop volumes and ample helo decks for sea strike and anti-submarine warfare — in a package that’s cheap to buy and operate. The ships come with built-in guns, launch tubes for self-defense and strike weapons, and hull-mounted sonar gear, and they can accept mission modules in hours to expand or tailor capabilities. The three Huitfeldts cost less than $1 billion.

The ships also are coveted during coalition operations for their 9,000-mile range at 15 knots, excellent sea-keeping qualities and command-and-control gear, plus spacious accommodations for command staffs. That’s why the Esbern Snare, the second of two Absalon support ships, is commanding the international flotilla in the Eastern Mediterranean that will destroy Syria’s chemical weapons.

Wikipedia has this image of the HDMS Iver Huitfeldt:

The class is built on the experience gained from the Absalon-class support ships, and by reusing the basic hull design of the Absalon class the Royal Danish Navy have been able to construct the Iver Huitfeldt class considerably cheaper than comparable ships. The frigates are compatible with the Danish Navy’s StanFlex modular mission payload system used in the Absalons, and are designed with slots for six modules. Each of the four Stanflex positions on the missile deck is able to accommodate either the Mark 141 8-cell Harpoon launcher module, or the 12-cell Mark 56 ESSM VLS.

While the Absalon-class ships are primarily designed for command and support roles, with a large ro-ro deck, the three new Iver Huitfeldt-class frigates will be equipped for an air defence role with Standard Missiles, and the potential to use Tomahawk cruise missiles, a first for the Danish Navy.

For contrast here is the HDMS Esbern Snare, the second ship in the Absalom class:

Danish Navy Combat Support Ship HDMS Esbern Snare in the port of Gdynia, prior to exercise US BALTOPS 2010.

That’s not to say that these particular ships would be a good fit for the RCN, but that the approach does seem to be viable (sharing common hull configurations and swappable mission modules). However, the efficiencies that could be achieved by following this practice would almost certainly be swamped by the political considerations to spread the money out over as many federal ridings as possible…

H/T to The Armourer for the link.

Powered by WordPress