Published on 26 Apr 2017

Our Patreon: http://patreon.com/thegreatwar

Our Merch Store: https://shop.spreadshirt.net/thegreatwar/A good explanation how YouTube Ads work by CGP Grey: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KW0eUrUiyxo

In light of the news surrounding YouTube and their ad policy we got a lot of comments asking how and if all this affects our show and production. We want to make a few things clear and also underline how you can support us.

» HOW CAN I SUPPORT YOUR CHANNEL?

You can support us by sharing our videos with your friends and spreading the word about our work.You can also support us financially on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/thegreatwarYou can also buy our merchandise in our online shop: http://shop.spreadshirt.de/thegreatwar/

Patreon is a platform for creators like us, that enables us to get monthly financial support from the community in exchange for cool perks.

April 27, 2017

Our Channel And The YouTube Adpocalypse I THE GREAT WAR

February 20, 2016

JOURNEYQUEST IS RENEWED!

Published on 19 Feb 2016

Thanks to over 5000 backers on Kickstarter, with mere hours to go, JourneyQuest has been renewed for a third season! Congratulations, thank you, and ONWAAAAAARD!

January 19, 2016

JourneyQuest Season 3 Kickstarter Begins

Published on 18 Jan 2016

JourneyQuest 3 is funding on Kickstarter now! Click here to renew the show for a third season: http://vid.io/xqEB

Now on Kickstarter! Renew JourneyQuest for an epic third season, featuring the ongoing adventures of Perf, a dyslexic wizard with a quest problem.Watch the first two seasons here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

November 29, 2015

Technological attempts to preserve Middle Eastern antiquities

Ars Technica calls them the digital “Monuments Men”:

The student who proclaimed this idea is part of a new generation of cultural guardians who are starting to make a name for themselves around the world as the digital “Monuments Men.” Originally the Monuments Men were a group of people, most of them with a cultural studies background, who joined a special branch of the US Army for one reason only: to save and retrieve stolen art from the Nazis. The goal of the digital Monuments Men today is no less important: they want to save global culture from destruction.

As a member of CyArk, Davison is providing tech and knowledge to those on-the-ground experts. The non-profit organisation has dedicated itself to digitising the UNESCO World Heritage sites. Within five years it plans to scan 500 cultural sites in order to transform them into digital 3D models. So far that has worked out quite well — at least for easily accessible examples such as the Brandenburg Gate in Germany or ancient Corinth in Greece. In crisis areas, failed states, and autocracies this task is a lot harder.

The CyArk organisation uses just about every tool that high-technology has to offer: 3D scanners, drones of every size, 360-degree cameras, 3D printers, smart software, and virtual reality systems. It seems as if the idea is certainly causing some serious stir: over 250 ambassadors, government officials, experts, and activists from 35 countries attended CyArk’s annual conference in Berlin this year.

In countries such as Syria, Iraq, or Libya thousands are fighting against the ongoing destruction of historical sites. They are working against time, against the environment, against natural catastrophes, and most of all against war. Since ISIS (ISIL, Daesh) started its mass destruction of historical and religious sites, the threat has become bigger. Not a week goes by without a new YouTube video popping up that shows monuments being blown into bits and pieces or destroyed by hammer-swinging terrorists.

Davison and his students are supposed to respond to ISIS with a secret offensive—and they’ve got the support of industrial and political elites.

There are other groups with slightly different approaches to preserving what can be preserved even if only through crowdsourced images to help create 3D models:

Other groups of cultural guardian activists rely more on Internet communities than secret data-smuggling. “Project Mosul,” for example, named after the city of Mosul in Iraq, uses Internet crowdsourcing, letting users upload their photos directly. Project Mosul also uses pictures of places they find on Flickr. The more photos they find, the easier it gets for them to create a 3D model of an endangered site.

If critical information is missing, members of the community reconstruct the rest. Scientifically this isn’t 100 percent accurate, but it is better than nothing. “I lived in Jordan for eleven years, and the destruction from Syria came so close, I had to do something,” says cofounder Matthew Vincent. Now his platform processes pictures from all around the world, not only Mosul.

In another interesting development, some companies are upgrading these 3D models into full virtual reality environments. David Fürsterwalder just founded his startup, realities.io — a company that specialises in “virtual tourism.” “We need to bring those places back to life instead of just preserving them,” he explains. Fürsterwalder is convinced that we stand on the brink of a VR revolution: “This is not only something for the museum. It will bring virtual journeys to every living room.”

November 15, 2015

A countertop home-brewing appliance

Pulkit Chandna reviews the “Brewie”:

In the future, at-home beer brewing will be a set-it-and-forget-it cinch, and not the convoluted mess we have always known it to be. That’s the feeling one gets from looking at Brewie, the latest in a series of countertop appliances designed to automate the process of beer crafting.

The Hungarian startup behind it claims Brewie is better and more automated than the competition — including the PicoBrew Zymatic home brewery we reviewed back in June. That lofty claim has helped the company secure hundreds of pre-orders, worth more than $600,000, across two crowdfunding rounds on Indiegogo. It concluded the first leg in February with a funding tally of $223,878, only to return to the site late last month in search of yet more pre-orders. (Indiegogo, as part of its “InDemand program” allows project creators to accept contributions or orders even after their crowdfunding campaign has ended.)

The Brewie is said to distill the whole brewing process down to a series of simple steps requiring negligible human input, such that even the most hopeless of aspiring brewmasters can get started with it in no time at all. You can control the unit either through its 4.3-inch LCD touchscreen or via the companion app over Wi-Fi.

June 25, 2015

A different kind of crowd-funding

Christopher Taylor starts off by praising to the skies a movie I’ve never seen … but he goes on to discuss a variant of crowdfunding that might be a significant change to how movies are made:

… the big studios are corporations that answer to a board of stockholders. And the stockholders aren’t interested in great film making, they are interested in making money off their stocks.

So the Broken Lizards guys went to crowdfunding to raise money for their film, and have done quite well. They did so well that they don’t need a big bunch of studio dollars and interference to make the movie.

But here’s where it gets really interesting. See, crowdfunding sites raise money by offering goodies and the joy of helping a product succeed. They are not investment sites so much as a chance to be a patron of something you want to see on the market as well as a chance to get something from the company. Free copies, a mention in the book, a token in the game named after you, and so on.

Well that’s all about to change in a big way.Jay Chandrasekhar writes:

At our meeting, I vented to Slava about my perception of crowdfunding. I told him I wished people could invest in the movie and then own an equity piece of the backend. He said, “I totally agree.” That’s when we hit it off. He said that there is legislation in Washington, as we speak, that if signed, will make equity-based crowdfunding a reality. Think about that.

I’m with Jay here. Think about that. Its very likely that soon you will be able to donate to a crowdfunded project and get money back from its sales. In other words, it will actually be an investment, not just patronizing.

This is a huge key in changing the way that media gets made. All those projects the studios and TV channels pass on because it isn’t hot or doesn’t make sense to them? If this happens, they can have a chance.

March 21, 2015

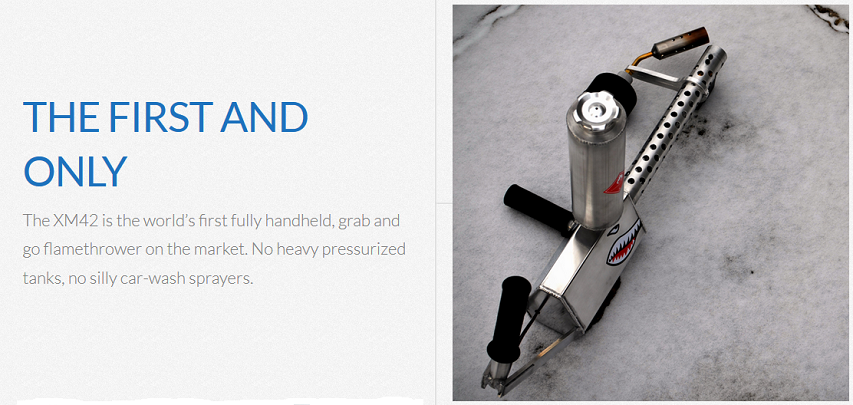

I know several people who’d want one of these

Want a new exotic toy to show off to your buddies after you say “Here, hold my beer”? How about a personal flamethrower?

November 21, 2014

Paging Delos D. Harriman – come to the Kickstarter courtesy phone, please

This is a use of crowdfunding I didn’t expect to see:

A group of British scientists have taken to Kickstarter in order to get the first set of funds to attempt a landing on the Moon. All ex-teenage (very much ex-teenage, sadly) sci-fi addicts like myself will obviously be cheering them on (and recalling Heinlein’s The Man Who Sold The Moon no doubt) and possibly even subscribing. They’re looking for £ 600,000 or so for the planning phase and will need £ 3 billion to actually carry out the mission. That’s probably rather more, that second number, than they can raise at Kickstarter.

However, over and above the simple joy of seeing boffins doing their boffinry there’s a further joy in the manner in which such projects disintermediate around the political classes. That is, we’ve not got to wait for the politicians to think this is a good idea, we’ve not even got to try and convince any of them that it is. We can (and seemingly are) just getting on with doing it ourselves.

[…]

Here’s what they’re proposing:

In arguably the most ambitious crowdfunded project ever attempted, a British team is planning to use public donations to fund a lunar landing.

Within ten years, they believe they can raise enough money to design, build and launch a spacecraft capable of not only travelling to the Moon, but drilling deep into its surface.

They also want to bury a time-capsule, containing digital details and DNA of those who have donated money to the venture as well alongside an archive of the history of Earth. Finally, the mission will assess the practicality of a permanent manned base at the lunar South Pole.

There’s no doubt at all that the Apollo and similar Russian space adventures had to be run by government. The technology of the time was such that only a government had the resources necessary to drive such a large project. But, obviously, the cost of rocket technology has come down over time.

November 18, 2014

The Wikipedia editors circle the wagons

Virginia Postrel talks about the greatest danger to the long-term health of Wikipedia — the diminishing central group of editors who do the most to keep it going:

Few of the tens of millions of readers who rely on Wikipedia give much thought to where its content comes from or why the site, which is crowdsourced and open (at least in theory) for anyone to edit, doesn’t degenerate into gibberish and graffiti. Like Google or running water, it is simply there. Yet its very existence is something of a miracle. Despite its ocean of content, this vital piece of informational infrastructure is the work of a surprisingly small community of volunteers. Only about 3,000 editors contribute more than 100 changes a month to the English-language Wikipedia, down from a high of more than 4,700 in early 2007. Without any central direction or outside recognition, these dedicated amateurs create, refine, and maintain millions of content pages.

But they don’t really do it for you. Wikipedia “is operated by and for the benefit of the editors,” writes Richard Jensen, one of their number, in a 2012 article in the Journal of Military History. (Jensen, a retired history professor, is a credentialed scholar, which makes him unusual among Wikipedia’s editors.) Unlike open-source software contributions, working on Wikipedia provides few career advantages. It’s a hobby, offering a combination of intrinsic and social rewards. People edit Wikipedia because they enjoy it.

And that is both the genius and the vulnerability of the organization. Wikipedia’s continued improvement — indeed, its continued existence — depends on this self-selected group of obsessives and the organizational culture they’ve developed over time. But the open structure that enabled the creation of so many entries on so many topics also attracts a never-ending stream of attacks from outright vandals and other bad actors. Forced to defend the site’s integrity, incumbent editors become skeptical, even hostile, toward the newcomers who could ensure its future. If Wikipedia eventually fades away, the reasons will lie in a culture that worked brilliantly until it devolved from dynamism to sclerosis.

May 11, 2014

Market disruption and innovation

Innovation often leads to challenges to established markets. Existing players in those established markets have three choices when faced with a disruptive new competitor or technological change: they can innovate themselves, they can retrench and avoid direct competition, or they can do what most incumbents do — get the government regulators to fight their battles for them.

Market incumbents do not like disruption. Uber, the ride-sharing service that has loosened the stranglehold of the taxi cartels, has been the object of government attacks and vigilante attacks both. Various regulatory agencies have tried with varying degrees of success to shut it down, London’s taxi drivers are even as we speak promising “chaos” in response to the firm’s success, French vigilantes have attacked its drivers, and in Seattle — blessed Seattle! — self-styled anarchists are targeting its cars and drivers. “Anarchists” for state-enforced cartel economics to increase private profit — somebody is unclear on the concept, it seems.

A great deal of the program of the old Left — from its full-on Marxist wing to its Proudhonian anarchist wing — is in the process of being accomplished by 21st-century capitalism. The means of production have been radically democratized, with multi-billion-dollar firms springing up out of garages and dorm rooms. The privileged position of dominant old-line financiers is being undermined rapidly by innovations such as Kickstarter, which blurs the line between the altruistic and the consumerist. The life expectancy of large corporations has collapsed, from about 75 years in the 1960s to 15 years and declining today. When Pierre-Joseph Proudhon called for “a war of labor against capital; a war of liberty against authority; a war of the producer against the non-producer; a war of equality against privilege,” he certainly did not have in mind Uber or Outbox; his most famous motto was, after all, “Property is theft.” (I think there is rather more to his idea of property than that simplistic formulation communicates, but this is not the place for that particular essay.) But the characteristics of those firms — relatively modest capital requirements, subverting various kinds of political authority in the form of licensure and regulation enacted in the interests of market incumbents, empowering efficient producers to compete with rent-seeking non-producers, and, above all, undermining the privileged place of state-sanctioned monopolies and cartels — looks a lot more like what the 19th-century revolutionaries had in mind than the USPS does. If what you mean by “capitalism” is the East India Company, then capitalism is not very attractive; if what you mean by “capitalism” is Kickstarter, then it is.

Not that a man transported from the 19th century to our own time would recognize that. If we could transport M. Proudhon or any of his contemporaries to the here and now, their eyes would not register any economic system with which they were familiar at the sight of the daily wonders we take for granted. They wouldn’t see capitalism; they’d see magic. But the DMV, the USPS, the housing project, and the prison would all be familiar to their 19th-century eyes. Our choice is not really between neat ideological verities with their roots in Adam Smith or Karl Marx, but between the DMV and the Apple store. Each model has its downsides, to be sure, but it does not seem like a terribly difficult choice to me.

April 2, 2014

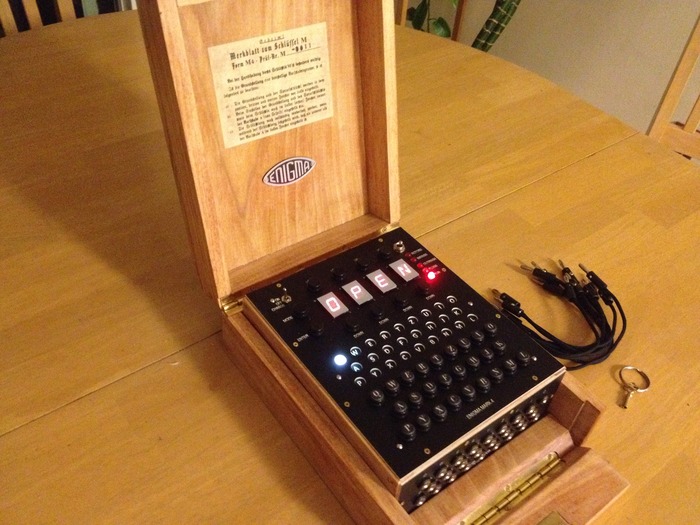

Enigma’s 21st century open sourced descendent

The Enigma device was used by the German military in World War 2 to encrypt and decrypt communication between units and headquarters on land and at sea. Original Enigma units — the few that are on the market at any time — sell for tens of thousands of dollars. You may not be able to afford an original, but you might be interested in a modern implementation of Enigma using Arduino-based open-source hardware and software:

Enigma machines have captivated everyone from legendary code breaker Alan Turing and the dedicated cryptographers from England’s Bletchley Park to historians and collectors the world over.

But while many history buffs would surely love to get their hands on an authentic Enigma machine used during WWII, the devices aren’t exactly affordable (last year, a 1944 German Enigma machine was available for auction at Bonhams with an estimated worth of up to $82,000). Enter the Open Enigma Project, a kit for building one from scratch.

The idea came to Marc Tessier and James Sanderson from S&T Geotronics by accident.

“We were working on designing and building intelligent Arduino-based open-source geocaching devices to produce a unique interactive challenge at an upcoming Geocaching Mega Event,” Tessier told Crave. “A friend of ours suggested we use an Enigma type encrypting/decrypting machine as the ultimate stage of the challenge and pointed us to an Instructables tutorial that used a kid’s toy to provide some Enigma encoding. We looked all over to buy a real Enigma machine even if we had to assemble it ourselves and realized that there was nothing available at the moment. So we decided to build our own.”

[…]

“Our version is an electronic microprocessor-based machine that is running software which is a mathematical expression of how the historical mechanical machine behaved,” Sanderson told Crave. “Having never touched a real Enigma M4, we built our open version based on what we read online. From what we understand, the real electro-mechanical devices are much heavier and a little bigger.”

They took some design liberties — replacing the physical rotors with LED units and replacing the light bulbs with white LEDs. The replica can be modified by changing the Arduino code and can communicate to any computer via USB. Future versions may include Wi-Fi and/or Bluetooth.

March 31, 2014

Market research, disguised as crowdfunding

Virginia Postrel has an interesting take on the current brouhaha over Facebook’s acquistion of formerly crowdfunded Oculus:

Crowdfunding sites such as Kickstarter and Indiegogo represent a classic entrepreneurial phenomenon: Once you roll out your great idea, customers use it in ways you didn’t imagine, and you wind up in a different business than you expected.

Kickstarter’s founders wanted to help artists raise money. Indiegogo co-founder Danae Ringelmann pictured aiding capital-strapped small-businesses owners like her parents. Neither intended their site to act as a test market. But, as the rags-to-riches story of virtual-reality firm Oculus shows, that’s what they have become.

“It’s a way to access capital, but what it’s also become is a market-testing and validation platform,” Ringelmann told the Dent the Future conference on Tuesday. “What we’re doing is creating pre-markets for ideas,” she said.

[…]

Now that Facebook is buying Oculus for $2 billion, critics are reverting to the original assumption that crowdfunding is primarily about raising money. “Talking people out of $2.4 million in exchange for zero percent equity is a perfectly legal scam,” wrote my colleague Barry Ritholtz.

But it’s not a scam at all. It’s market research. In effect, customers placed pre-orders and received early products; why are they griping that they don’t own a part of the business?

The backlash is largely Kickstarter’s fault. It may not be running a scam, but it definitely sends mixed messages. Unlike Indiegogo, which prides itself on operating a neutral platform giving anybody’s idea a market test, Kickstarter hasn’t embraced its de facto transformation. It strictly curates the campaigns it hosts and, although it makes its biggest profits on technology products, it still exudes an artistic sensibility that isn’t entirely comfortable with disruptive technology or large enterprises. It still talks as though it’s PBS. “Kickstarter is not a store,” it declares.

March 26, 2014

Oculus in the news

Raph Koster reflects on the promise of Oculus:

Rendering was never the point.

Oh, it’s hard. But it’s rapidly becoming commodity hardware. That was in fact the basic premise of the Oculus Rift: that the mass market commodity solution for a very old dream was finally approaching a price point where it made sense. The patents were expiring; the panels were cheap and getting better by the month. The rest was plumbing. Hard plumbing, the sort that calls for a Carmack, maybe, but plumbing.

[…]

Look, there are a few big visions for the future of computing doing battle.

There’s a wearable camp, full of glasses and watches. It’s still nascent, but its doom is already waiting in the wings; biocomputing of various sorts (first contacts, then implants, nano, who knows) will unquestionably win out over time, just because glasses and watches are what tech has been removing from us, not getting us to put back on. Google has its bets down here.

There’s a beacon-y camp, one where mesh networks and constant broadcasts label and dissect everything around us, blaring ads and enticing us with sales coupons as we walk through malls. In this world, everything is annotated and shouting at a digital level, passing messages back and forth. It’s an ubicomp environment where everything is “smart.” Apple has its bets down here.

These two things are going to get married. One is the mouth, the other the ears. One is the poke, the other the skin. And then we’re in a cyberpunk dream of ads that float next to us as we walk, getting between us and the other people, our every movement mined for Big Data.

[…]

The virtue of Oculus lies in presence. A startling, unusual sort of presence. Immersion is nice, but presence is something else again. Presence is what makes Facebook feel like a conversation. Presence is what makes you hang out on World of Warcraft. Presence is what makes offices persist in the face of more than enough capability for remote work. Presence is why a video series can out-draw a text-based MOOC and presence is why live concerts can make more money than album sales.

Facebook is laying its bet on people, instead of smart objects. It’s banking on the idea that doing things with one another online — the thing that has fueled it all this time — is going to keep being important. This is a play to own walking through Machu Picchu without leaving home, a play to own every classroom and every museum. This is a play to own what you do with other people.

Update: Apparently some of the folks who backed the original Kickstarter campaign have their panties in a bunch now that there’s big money involved.

Attendees wear Oculus Rift HD virtual reality head-mounted displays as they play EVE: Valkyrie, a multiplayer virtual reality dogfighting shooter game, at the Intel booth at the 2014 International CES, January 9, 2014 in Las Vegas, Nevada. ROBYN BECK/AFP/Getty Images

Facebook’s purchase of virtual reality company Oculus for $2bn in stocks and shares is big news for a third company: Kickstarter, which today celebrates the first billion-dollar exit of a company formed through the crowdfunding platform.

Oculus raised $2.4m for its Rift headset in September 2012, exceeding its initial fundraising goal by 10 times. It remains one of the largest ever Kickstarter campaigns.

But as news of the acquisition broke Tuesday night, some of the 9,500 people who backed the project for sums of up to $5,000 a piece (the most popular package, containing an early prototype of the Rift, was backed by 5,600 for a more reasonable $300) were rethinking their support.

[…]

For Kickstarter itself, the purchase raises awkward questions. The company has always maintained that it should not be viewed as a storefront for pre-ordering products; instead, a backer should be aware that they are giving money to a struggling artist or designer, and view the reward as a thanks rather than a purchase.

“Kickstarter Is Not a Store” is how the New York-based company put it in 2012, shortly after the Oculus Rift campaign closed. Instead, the company explained: “It’s a new way for creators and audiences to work together to make things.”

But if Kickstarter isn’t a store, and if backers also aren’t getting equity in the company which uses their money to build a $2bn business, then what are they actually paying for?

“Structurally I have an issue with it,” explains Buckenham, “in that the backer takes on a great deal of risk for relatively little upside and that the energy towards exciting things is formalised into a necessarily cash-based relationship in a way that enforces and extends capitalism into places where it previously didn’t have total dominion.”

March 11, 2014

Surveillance game – Nothing to Hide

If you’re not worried about the government (or other governments) watching your every move — because you’ve “got nothing to hide” — you might be interested in this game:

The tongue-in-cheek game Nothing to Hide was born out of creator Nicky Case’s dedication to privacy rights. Using the game, he intends to chip away at confidence in National Security Agency (NSA) procedures and give advocates something to think about.

The “anti-stealth” framework is an “inversion” of more familiar stealth-based video games. In the Panopticon-inspired environment, players must control behavior to please monitoring powers. Rather than avoid surveillance equipment, players actively work to remain in sight of yellow, triangle cyclops-eyed cameras. If a player walks outside the view of the camera, he or she risks death by summary, trial-free execution — because clearly he or she is a criminal with something to hide.

The name Nothing to Hide is, of course, taken from a common blasé reaction to state surveillance: “Well, I’ve got nothing to hide.” The game confronts this attitude by drawing attention to the unpleasantness of being constantly monitored. Players are thrust into a dystopian environment devoid of privacy. Digital posters with creepy comments like “Smile for the camera” and “Thank you for participating in your own surveillance” cover the walls.

March 8, 2014

“If you would like a refund, please contact a fan of my work directly for your money”

Reason‘s Brian Doherty reports on a fascinating Kickstarter campaign by comic artist John Campbell:

For those who think Ayn Rand was just crazily overwrought in the “unrealistic” characters she created to dramatize the anti-capitalist mentality, you might want to see this addendum to the Kickstarter page of comic artist John Campbell, who raised over $50,000 on Kickstarter to publish a book of his comics Sad Pictures for Children.

He got tired of having to mail the books he promised, apparently (believe me, I know that’s a drag) and so decided to burn a copy for every person who asked about where the book they’d been promised was.

The page has a video of him doing the burning.

He has elevated the annoyance of mailing 127 packages to an anti-market rant of marvelous proportion. Excerpts, though whole thing is worth reading, after he talks about how rich people he knew as a kid mistreated a pet rat:

I got a lot of requests from backers to get books sent before Christmas, which I was able to do for some people. I could not do this for other people before leaving for the holidays, and many of them asked for refunds.

I refunded them with money I got from selling the original art I made for my webcomic from 2009-2012. This was money I planned to ship orders with. After this happened, I could have made another update explaining I had issued refunds and then tried to sell more things or asked for more shipping money. Instead I thought for a long time about what has been happening…

If you would like a refund, please contact a fan of my work directly for your money. This is where the money would come from anyway. I am cutting out the middle man.