Forgotten Weapons

Published on 10 Feb 2019http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

What is the difference between patents and copyrights? If someone wants to reproduce an old firearm design, how do they get the rights to? Why can’t you reproduce a gun design from patent drawings? What information is in a technical data package? This and more, today on How Does It Work!

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

PO Box 87647

Tucson, AZ 85754

March 11, 2019

How Does It Work: Patents and Blueprints

January 29, 2019

Bell Canada wants the feds to crack down on Virtual Private Networks

Michael Geist discusses some revelations from Bell’s communications with the federal government during the NAFTA negotiations:

Just days after Bell spoke directly with a CRTC commissioner in the summer of 2017 seeking to present on its site blocking proposal to the full commission, it asked Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland to target VPNs as Canada’s key copyright demand in the trade talks. Its submission to the government stated:

The Canadian cultural industry has long been significantly harmed by the use of virtual-private-network (VPN) services, which facilitate the circumvention of technological protection measures put in place to respect copyright ownership in other jurisdictions such as Canada…When the ability to enforce rights in national markets breaks down it inevitably favours the largest markets (which become the de facto “global” market) at the expense of smaller open economies like Canada. This harms Canada both economically and culturally.

Canada should seek rules in NAFTA that require each party to explicitly make it unlawful to offer a VPN service used for the purpose of circumventing copyright, to allow rightsholders from the other parties to enforce this rule, and to confirm that is a violation of copyright if a service effectively makes content widely available in territories in which it does not own the copyright due to an ineffective or insufficiently robust geo-gating system.

This is precisely the concern that was raised in the context of the Bell coalition blocking system given fears it would expand to multi-use services such as VPNs just as a growing number of Internet users are turning to the technology to better safeguard their privacy and prevent online tracking.

In fact, the Bell submission went even further than just VPNs, urging the government to consider additional legal requirements on ISPs to enforce copyright rules:

Notice-and-notice has been a very incomplete solution to the problem of widespread digital piracy. While we do not believe it should be eliminated, the Government should explore other ways to secure the cooperation of service providers whose services are used for piracy (such as the site-blocking regimes required in Europe and also in place in many other countries throughout the world).

June 27, 2018

Canada’s odd approach to open data

Michael Geist the contrast between what the Canadian government says about access to information and what they actually do:

The Liberal government has emphasized the importance of open data and open government policies for years, yet the government has at times disappointed in ways both big (Canada’s access-to-information laws are desperately in need of updating and the current bill does not come close to solving its shortcomings) and small (restrictive licensing and failure to comply with access to information disclosures).

For example, late last year, I noted that government departments had oddly adopted a closed-by-default approach to posting official photographs on Flickr. Unlike many other governments that use open licenses or a public domain approach, Canadians looking for openly licensed photographs for inclusion in learning materials, blog posts, or other content must rely on foreign governments. The restrictive licensing approach remains in place: those seeking photos on Flickr from the G7 will find Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s are “all rights reserved” but other governments attending the summit – including the United States, United Kingdom, Norway, and South Africa – all facilitate re-use of their photos through open licensing.

A restrictive approach to disclosing information about completed access-to-information requests has also emerged in recent months. Open disclosure of the completed requests benefits both the public and the government. For the public, completed requests are there for the asking as they can be obtained on an informal basis at no cost. For the government, completed requests can sometimes provide the information requested by the public, thereby reducing costs and saving time for government officials. For many years, the government maintained a database known as CAIRS, which featured lists of completed access to information requests. After that was cancelled, the government created an open government page that includes the last two years of requests (the information is searchable or downloadable). According to the site:

Government of Canada institutions subject to the Access to Information Act (ATIA) are required to post summaries of processed ATI requests. You can search these summaries, which are available within 30 calendar days after the end of the month. Searches can be made by keywords, topic or field of interest. If you find a summary of interest, you can also request a copy of the previously released ATIA records.

But you can’t access them until they’ve been published, and several government departments are as much as a year behind in making these records available.

June 24, 2018

Berlin protest planned against EU’s proposed copyright changes

If you’re a regular internet user and you’re anywhere near Berlin, you might want to consider supporting this protest:

On Wednesday, the Legislative Committee of the European Union narrowly voted to keep the two most controversial internet censorship and surveillance proposals in European history in the upcoming revision to the Copyright Directive — as soon as July Fourth, the whole European Parliament could vote to make this the law of 28 EU member-states.

The two proposals were Article 11 (the link tax), which bans linking to news articles without paying for a license from each news-site you want to link to; and Article 13 (the copyright filters), requiring that everything that Europeans post be checked first for potential copyright infringements and censored if an algorithm decides that your expression might breach someone’s copyright.

These proposals were voted through even though experts agree that they will be catastrophic for free speech and competition, raising the table-stakes for new internet companies by hundreds of millions of euros, meaning that the US-based Big Tech giants will enjoy permanent rule over the European internet. Not only did the UN’s special rapporteur on freedom of expression publicly condemn the proposal; so did more than 70 of the internet’s leading luminaries, including the co-creators of the World Wide Web, Wikipedia, and TCP.

We have mere days to head this off: the German Pirate Party has called for protests in Berlin this Sunday, June 24 at 11:45h outside European House Unter den Linden 78, 10117 Berlin. They’ll march on the headquarters of Axel-Springer, a publisher that lobbied relentlessly for these proposals.

If you use the Internet to communicate, organize, and educate it’s time to speak out. Show up, stand up, because the Internet needs you!

Original post, with embedded links, at BoingBoing.

June 20, 2018

Do You Have a Right To Repair Your Phone? The Fight Between Big Tech and Consumers

ReasonTV

Published on 18 Jun 2018Eric Lundgren got 15 months in prison for selling pirated Microsoft software that the tech giant gives away for free. His case cuts to the heart of a major battle going on in the tech industry today: Companies are trying to preserve aspects of U.S. copyright law that give them enormous power over the products we own.

Reason is the planet’s leading source of news, politics, and culture from a libertarian perspective. Go to reason.com for a point of view you won’t get from legacy media and old left-right opinion magazines.

April 12, 2018

Canadian Music Policy Coalition pushes to revive the idea of an “iPod tax”

Michael Geist on one particular rent-seeking submission to the federal government pushing for changes to Canadian copyright law:

The long-awaited Canadian copyright review is set to kick off hearings next week as a House of Commons committee embarks on a year-long process that will hear from a wide range of stakeholders. My Globe and Mail op-ed notes that according to documents obtained under the Access to Information Act, however, one stakeholder – the Canadian Music Policy Coalition, an umbrella group representing 17 music associations – got an early start on the review process last fall by quietly submitting a 30-page reform proposal to government officials.

The proposal, titled “Sounding Like a Broken Record: Principled Copyright Recommendations from the Music Industry”, calls for radical changes that would spark significant new consumer fees and Internet regulation. The plan features new levies on smartphones and tablets, Internet service provider tracking of subscribers and content blocking, longer copyright terms, and even the industry’s ability to cancel commercial agreements with Internet companies if the benefits from the deal become “disproportionate.”

The coalition, which includes the Canadian Council of Music Industry Associations, the Canadian Music Publishers Association, and copyright collectives such as SOCAN, asks the government to follow three main principles as part of its reform process: real-world applicability, forward-thinking rights, and consistent rules.

But the coalition proposal largely avoids discussing the current state of the industry, perhaps with the intent of leaving some with the impression that file sharing remains a significant problem. The reality is the music industry in Canada, led by the massive growth of authorized music streaming services, has enjoyed a remarkable string of successes since the last time copyright law was overhauled in 2012.

The Canadian music market is growing much faster than the world average, with Canada jumping past Australia last year to become the sixth largest music market in the world. Music collective SOCAN, a coalition member, has seen Internet streaming revenues balloon from $3.4 million in 2013 to a record-setting $49.3 million in 2017.

Moreover, data confirms that music piracy has diminished dramatically in Canada. Music Canada reports that Canada is below global averages for “stream ripping”, the process of downloading streamed versions of songs from services such as YouTube. Last month Sandvine reported that file sharing technology BitTorrent is responsible for only 1.6 per cent of Canadian Internet traffic, down from as much as 15 per cent in 2014.

Yet despite the success of Internet streaming services and the marginalization of file sharing activity, the coalition has crafted a reform proposal that would be more at home in 2008 than in 2018. For example, the industry is now calling for new fees to be set by the Copyright Board on all smartphones and tablets to compensate for personal copying. The revival of the so-called “iPod tax” would today go far further than just digital music players, as the coalition is asking the government to amend the Copyright Act to allow for fees to be imposed on all devices.

April 10, 2018

New Year’s Day in 2019 will be a big day for works finally entering public domain

The US government messed around with the copyright laws so that from 1998 until the end of this year, very little material was allowed to slip out of copyright protection and into the public domain. (Many people point their fingers at the Disney corporate lawyers and their pliable friends in Washington DC for this oddity.) In The Atlantic, Glenn Fleishman explains some of the legal issues that will finally begin to allow works to enter public domain status in the US normally next year:

The Great American Novel enters the public domain on January 1, 2019 — quite literally. Not the concept, but the book by William Carlos Williams. It will be joined by hundreds of thousands of other books, musical scores, and films first published in the United States during 1923. It’s the first time since 1998 for a mass shift to the public domain of material protected under copyright. It’s also the beginning of a new annual tradition: For several decades from 2019 onward, each New Year’s Day will unleash a full year’s worth of works published 95 years earlier.

This coming January, Charlie Chaplin’s film The Pilgrim and Cecil B. DeMille’s The 10 Commandments will slip the shackles of ownership, allowing any individual or company to release them freely, mash them up with other work, or sell them with no restriction. This will be true also for some compositions by Bela Bartok, Aldous Huxley’s Antic Hay, Winston Churchill’s The World Crisis, Carl Sandburg’s Rootabaga Pigeons, e.e. cummings’s Tulips and Chimneys, Noël Coward’s London Calling! musical, Edith Wharton’s A Son at the Front, many stories by P.G. Wodehouse, and hosts upon hosts of forgotten works, according to research by the Duke University School of Law’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain.

Throughout the 20th century, changes in copyright law led to longer periods of protection for works that had been created decades earlier, which altered a pattern of relatively brief copyright protection that dates back to the founding of the nation. This came from two separate impetuses. First, the United States had long stood alone in defining copyright as a fixed period of time instead of using an author’s life plus a certain number of years following it, which most of the world had agreed to in 1886. Second, the ever-increasing value of intellectual property could be exploited with a longer term.

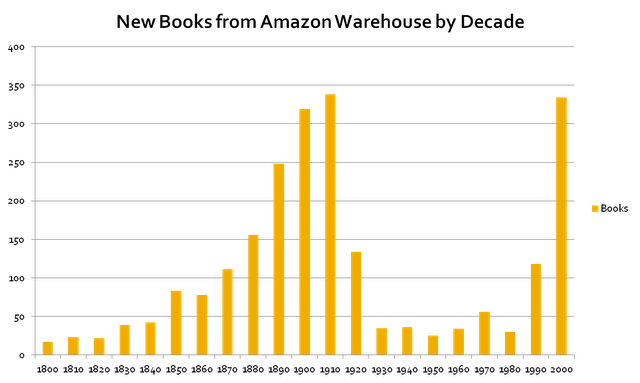

Here’s a graphical representation of how the copyright laws interact with Amazon’s ability/interest in stocking or otherwise making available older still-in-copyright works (graphic from 2015):

So, what’s the Disney connection?

The details of copyright law get complicated fast, but they date back to the original grant in the Constitution that gives Congress the right to bestow exclusive rights to a creator for “limited times.” In the first copyright act in 1790, that was 14 years, with the option to apply for an automatically granted 14-year renewal. By 1909, both terms had grown to 28 years. In 1976, the law was radically changed to harmonize with the Berne Convention, an international agreement originally signed in 1886. This switched expiration to an author’s life plus 50 years. In 1998, an act named for Sonny Bono, recently deceased and a defender of Hollywood’s expansive rights, bumped that to 70 years.

The Sonny Bono Act was widely seen as a way to keep Disney’s Steamboat Willie from slipping into the public domain, which would allow that first appearance of Mickey Mouse in 1928 from being freely copied and distributed. By tweaking the law, Mickey got another 20-year reprieve. When that expires, Steamboat Willie can be given away, sold, remixed, turned pornographic, or anything else. (Mickey himself doesn’t lose protection as such, but his graphical appearance, his dialog, and any specific behavior in Steamboat Willie — his character traits — become likewise freely available. This was decided in a case involving Sherlock Holmes in 2014.)

The reason that New Year’s Day 2019 has special significance arises from the 1976 changes in copyright law’s retroactive extensions. First, the 1976 law extended the 56-year period (28 plus an equal renewal) to 75 years. That meant work through 1922 was protected until 1998. Then, in 1998, the Sonny Bono Act also fixed a period of 95 years for anything placed under copyright from 1923 to 1977, after which the measure isn’t fixed, but based on when an author perishes. Hence the long gap from 1998 until now, and why the drought’s about to end.

March 6, 2018

Playboy‘s extortion attempt against Boing Boing dismissed

Back in January, I linked to the bizarre story of Playboy attempting to sue Boing Boing for the terrible crime of … linking. On the web. I’m not making this up. Thankfully, common sense finally did triumph as reported on Monday:

In January, we let you know that Playboy had sued us. On Valentine’s Day, a court tossed their ridiculous complaint out, skeptical that Playboy could even amend it. Playboy didn’t bother to try.

We are grateful this is over. We are grateful for the wonderful work of the EFF, Durie Tangri, and Blurry Edge, our brilliant attorneys who stood up to Playboy‘s misguided and imaginary claims. We are glad the court quickly saw right through them.

Playboy damaged our business. This lawsuit cost our small team of journalists, artists and creators time and money that would otherwise have been focused on Boing Boing‘s continued mission to share wonderful things.

February 19, 2018

Google disappears the “View Image” button from their image search page

At Ars Technica, Ron Amadeo explains what happened:

This week, Google Image Search is getting a lot less useful, with the removal of the “View Image” button. Before, users could search for an image and click the “View Image” button to download it directly without leaving Google or visiting the website. Now, Google Images is removing that button, hoping to encourage users to click through to the hosting website if they want to download an image.

Google’s Search Liaison, Danny Sullivan, announced the change on Twitter yesterday, saying it would “help connect users and useful websites.” Later Sullivan admitted that “these changes came about in part due to our settlement with Getty Images this week” and that “they are designed to strike a balance between serving user needs and publisher concerns, both stakeholders we value.”

[…] Adhering to copyright law is still the user’s responsibility, and a whole lot of images on the Web aren’t locked down under copyright law. There are tons of public domain and creative commons images out there (like everything on Wikipedia, for instance), and lots of organizations are free to use many copyrighted images under fair use. There are also many times when content on a page will change, and the “visit site” button will go to a webpage that doesn’t have the image Google told you it had.

For users who want to stick with Google, the image previews you see are actually hot-linked images, so right clicking and choosing “open image in new tab” (or whatever your equivalent browser option is) will still get you a direct image link. There is also already an open source browser extension called “Make Google Image Search Great Again” that will restore the “View Image” button. But if you’re looking to dump Google over this change, Bing and DuckDuckGo continue to offer “View Image” buttons.

Concerns about copyright are a big reason I tend to use Wikimedia or other clearly public domain images when I want to add one to a blog post.

January 19, 2018

Playboy sues Boing Boing for … linking?

I thought this sort of legal stupidity went out with the 90s …

A few weeks ago we were shocked to learn that Playboy had, without notifying us, sued us over this post (we learned about it when a journalist DM’ed us on Twitter to ask about it). Today, we filed a motion to dismiss, asking the judge to throw out this baseless, bizarre case. We really hope the courts see it our way, for all our sakes.

Playboy’s lawsuit is based on an imaginary (and dangerous) version of US copyright law that bears no connection to any US statute or precedent. Playboy — once legendary champions for the First Amendment — now advances a fringe copyright theory: that it is illegal to link to things other people have posted on the web, on pain of millions in damages — the kinds of sums that would put us (and every other small publisher in America) out of business.

Rather than pursuing the individual who created the allegedly infringing archive, Playboy is pursuing a news site for pointing out the archive’s value as a historical document. In so doing, Playboy is seeking to change the legal system so that deep-pocketed opponents of journalism can shut down media organizations that displease them. It’s a law that they could never get from Congress, but which they hope the courts will conjure into existence by wiping us off the net.

It’s not just independent publishers who rely on the current state of copyright law, either. Major media outlets (like Playboy!) routinely link and embed media, without having to pay a lawyer to research the copyright status of something someone else posted, before discussing, explaining or criticizing it.

The world can’t afford a judgment against us in this case — it would end the web as we know it, threatening everyone who publishes online, from us five weirdos in our basements to multimillion-dollar, globe-spanning publishing empires like Playboy.

As a group of people who have had long associations with Playboy, reading the articles (really!) and sometimes writing them, we hope the judge sees it our way — for our sakes… and for Playboy‘s.

August 4, 2017

QotD: Shakespeare’s sonnets

The Sonnets were published late in Shakespeare’s career (1609) — by a clever and unscrupulous man. His name was Thomas Thorpe. He ran what was for the times a unique publishing business, playing games with “copyright” that were often unconscionable but, usually, this side of the law. He owned neither a printing press, nor a bookstall — two things that defined contemporary booksellers — subcontracting everything in his slippery way. Indeed, I would go beyond other observers, and describe him as a blackguard; and I think Will Shakespeare would agree with me. Though Shakespeare would add, “A witty and diverting blackguard.”

He collected these sonnets, quite certainly by Shakespeare, but written at much different times and for quite various occasions, from whatever well-oiled sources. Thorpe had a fine poetic ear, and knew what he was doing. He arranged the collection he’d amassed in the sequence we have inherited — 154 sonnets that seem to read consecutively, with “A Lover’s Complaint” tacked on as their envoi — then sold them as if this had been the author’s intention.

We have sonnets not later than 1591, interspersed with others 1607 or later. In one case (Sonnet 145), we have what I think is a love poem Shakespeare wrote about age eighteen, to a girl he was wooing: one Anne Hathaway. (She was twenty-seven.) It is crawling with puns, for instance on her name, and stylistically naïve, but has been placed within the “Dark Lady” sonnets (127 to 152) in a mildly plausible way. It hardly belongs there.

Indeed, once one sees this it becomes apparent, surveying the whole course, that there is rather more than one “Dark Lady” in the Sonnets, and that like most red-blooded men, our Will noticed quite a number of interesting women over his years. But Thorpe has folded them all into one for dramatic effect.

David Warren, “Dark gentleman of the Sonnets”, Essays in Idleness, 2015-05-11.

July 28, 2016

Canada’s National Heritage Digitization “Strategy”

Michael Geist explains why the federal government’s plans for digitization are so underwhelming:

Imagine going to your local library in search of Canadian books. You wander through the stacks but are surprised to find most shelves barren with the exception of books that are over a hundred years old. This sounds more like an abandoned library than one serving the needs of its patrons, yet it is roughly what a recently released Canadian National Heritage Digitization Strategy envisions.

Led by Library and Archives Canada and endorsed by Canadian Heritage Minister Mélanie Joly, the strategy acknowledges that digital technologies make it possible “for memory institutions to provide immediate access to their holdings to an almost limitless audience.”

Yet it stops strangely short of trying to do just that.

My weekly technology law column notes that rather than establishing a bold objective as has been the hallmark of recent Liberal government policy initiatives, the strategy sets as its 10-year goal the digitization of 90 per cent of all published heritage dating from before 1917 along with 50 per cent of all monographs published before 1940. It also hopes to cover all scientific journals published by Canadian universities before 2000, selected sound recordings, and all historical maps.

The strategy points to similar initiatives in other countries, but the Canadian targets pale by comparison. For example, the Netherlands plans to digitize 90 per cent of all books published in that country by 2018 along with many newspapers and magazines that pre-date 1940.

Canada’s inability to adopt a cohesive national digitization strategy has been an ongoing source of frustration and the subject of multiple studies which concluded that the country is falling behind. While there have been no shortage of pilot projects and useful initiatives from university libraries, Canada has thus far failed to articulate an ambitious, national digitization vision.

December 2, 2015

What did the ministry officials tell new minister Mélanie Joly about copyright?

Michael Geist commends the federal government for transparency when they published the briefing information provided to new Heritage minister Mélanie Joly, but points out that the information isn’t complete:

Last week, Canadian Heritage posted the Ministerial briefing book that officials used to bring new minister Mélanie Joly up-to-speed on the issues in her portfolio. The proactive release is a great step toward further transparency. While the mandate letter from the Prime Minister provides insight into government policy priorities, the briefing book sheds light on what department officials view as priorities and how they frame key issues.

The copyright presentation is particularly revealing since it presents Minister Joly with a version of Canadian copyright lacking in balance in which “exceptions are always subject to certain conditions” but references to similar limitations on rights themselves are hard to find. Department officials present a frightening vision of emerging copyright issues, pointing to mandated Internet provider blocking, targeting copyright infringement that occurs on virtual private networks, and “hybrid” legal/illegal services that may be a reference to Canadians accessing U.S. Netflix. The suggestion that Canadian Heritage officials have identified site blocking or legal prohibitions on VPN or U.S. Netflix usage as emerging copyright issues should set off alarm bells well in advance of the 2017 copyright reform process.

So what didn’t officials tell Minister Joly? The reality is that the Minister would benefit from a second presentation that discusses issues such as:

- the emergence of technological neutrality as a principle of copyright law

- how Canada may be at a disadvantage relative to the U.S. given the absence of a full fair use provision

- the growth of alternate licensing systems such as Creative Commons

- how term extension for sound recordings was passed even though the issue was scarcely raised during the 2012 reform process

- why extending the term of copyright (as proposed by the TPP) would do enormous harm to Canadian heritage.

Yet none of these issues are discussed in the briefing.

November 20, 2015

Canada’s dubious gains from the TPP

Michael Geist gives an overview of the pretty much complete failure of Canadian negotiators to salvage anything from the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement:

The official release of the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), a global trade agreement between 12 countries including Canada, the United States, and Japan, has sparked a heated public debate over the merits of the deal. Leading the opposition is Research in Motion founder Jim Balsillie, who has described the TPP as one of Canada’s worst-ever policy moves that could cost the country billions of dollars.

My weekly technology law column […] notes that as Canadians assess the 6,000 page agreement, the implications for digital policies such as copyright and privacy should command considerable attention. On those fronts, the agreement appears to be a major failure. Canadian negotiators adopted a defensive strategy by seeking to maintain existing national laws and doing little to extend Canadian policies to other countries. The result is a deal that the U.S. has rightly promoted as “Made in America.” [a video of my recent talk on this issue can be found here].

In fact, even the attempts to preserve Canadian law were unsuccessful. The TPP will require several important changes to domestic copyright rules including an extension in the term of copyright that will keep works out of the public domain for an additional 20 years. New Zealand, which faces a similar requirement, has estimated that the extension alone will cost its economy NZ$55 million per year. The Canadian cost is undoubtedly far higher.

In addition to term extension, Canada is required to add new criminal provisions to its digital lock rules and to provide the U.S. with confidential reports every six months on efforts to stop the entry of counterfeit products into the country.

November 19, 2015

“Changing Canada’s copyright term … means two decades where zero historical work enters the public domain”

There may be good parts of the Trans-Pacific Partnership deal, but there are emphatically bad parts, as Jesse Schooff describes in the particular case of the arbitrary extension of copyright in Canada from fifty years to seventy years:

One of the TPP areas of scope which is critical to discuss is the section on copyright. At this point, several notable bloggers* have covered the TPP’s copyright extension provisions in great detail. But what do those provisions mean for you? Let’s bring it down to the ground. For example: folks in my demographic seem to love seeing old-timey photos of their city. Here in Vancouver, exploring our retro-downtown through old photographs of various eras is practically an official pastime.

A quality source of such photo collections is a city’s municipal archives. Traditionally, an archives’ mandate is to store physical objects and documents, which include the physical “analog” photos taken during most of the 20th century. “Great!” someone might say, “the archives can just digitize those photos and put them up on their website, right?”

Let’s ignore the fact that the solution my strawperson proposes has a host of logistical issues attached, not the least of which is the thousands of work-hours required to digitize physical materials. Our focus is copyright — just because the archives has the original, physical photo in their collection doesn’t mean that they own the rights to it.

You have to remember that our newfangled, internet-enabled society is relatively new. When I was a child, if a person wanted to see a historical photo from a city archives, they would actually have to physically GO to said archives and ask an archivist to retrieve the appropriate fonds containing the photo. Journalists and other professionals likely did this regularly, but for the most part, the public at large didn’t usually head down to a municipal building and ask an archivist to search through their collection just to look at a few old photos.

Today, things are much different. If a municipal archives has digitized a significant portion of, say, their collection of 19th and 20th century historical photos, then those photos can be curated online; made accessible to the public at large for everyone to access, learn from, and enjoy!

[…]

Some of the photos, we’ll call them “Group A”, were explicitly released into the public domain by the photographer, so those are okay to use. Another bunch, “Group B”, are photos whose photographer died more than fifty years ago (1965 and before); any copyright on these photos is expired. Some “Group C” photos were commissioned by a businesses, or the rights were specifically sold to a corporation, which means that the archives will have to get permission or pay a fee to make them available online. Most frustrating is the big “Group D”, whose authorship/ownership is sadly ambiguous, for various reasons**. It would be risky for the archives to include the Group D photos in their collection, since they might be violating the copyright of the original author.

So already, knowing and managing the tangle of copyright laws is a huge part of curating these event photos. Hang on, because the TPP is here to make it even worse.

It’s been long-known that the United States is very set on a worldwide-standard copyright term of seventy years from the death of the author. Sadly, such a provision made it into the TPP. Worse still, a release by New Zealand’s government indicates that this change could be retroactive, meaning that those photos in my hypothetical “Group B” would be yanked out of the public domain and put back under copyright.